— Tombstone set photos By Bob Boze Bell —

You can’t have an authentic set without authentic costumes. But even though Tombstone would begin filming more than two months before the start of Wyatt Earp, both productions were still competing for the same wardrobes…and Kevin Costner had already usurped all of Hollywood’s available Western costumes for his film.

As a result, the producers of Tombstone were forced to look elsewhere. Kurt Russell, who would later admit to True West that he was the director behind the 1993 blockbuster Western, wasn’t overly bothered. “That didn’t hurt,” he admitted. “It forced us to go to Europe, which, in fact, is where the nouveau riche of Tombstone bought their clothes in the first place.”

Screenwriter Kevin Jarre’s attention to detail was paying off in atmospheric richness, but at what expense? The original wardrobe budget was estimated at $402,692, but due to availability issues, the budget subsequently increased to $544,286. Several costume designer applicants submitted their portfolios and were interviewed, but they failed to realize Jarre’s envisioned concept. Brown, beige and earth tones were not what he wanted.

“If you look at clothes left from that period, if you look at wallpaper samples and paint samples and books, people have very wild use of color, they use lime green and purples and very jarring color schemes. This director really wanted to see that because a lot of Westerns, they do go for that sepia-tone brown, amber, gold,” Tombstone Production Designer Catherine Hardwicke says.

Costume designer Joseph Porro had never worked on a Western before: The Blob, Fright Night Part 2, Death Warrant, Kickboxer 2, Universal Soldier, among others, but no Westerns or period films.

“Actually, I did a Western-style vampire film in the ’80s before Tombstone,” Porro admits. “It was called Near Dark. But it was modern day, so that probably even wouldn’t count. It wasn’t a classic Western. I really didn’t have much period experience on my resume or any Westerns, but I went to the interview dressed in vintage Western clothing and [Jarre] just loved it. That had a lot to do with me getting [the job], and I brought a lot of research and information with me.”

He desperately needed such material because at least four Westerns were in simultaneous pre-production: Tombstone and Wyatt Earp, and both Geronimo and Geronimo: An American Legend.

“It made it really, really tough,” Porro says. “There wasn’t even a cowboy hat left [to rent] anywhere at any of the studios. And I freaked out.… American [Costume] wouldn’t let me rent from them.

“Kevin was going to use Luster Bayless. Then he heard of some problems with Luster, so he passed on him, and he ended up with me. And then I stupidly go to [American] and [Luster’s] angry because he just got fired from Tombstone. I had no idea that he even had been involved with it. He sits there and berates me for 15 minutes, and tells me to leave his costume house.

“So the only other costume houses are Warner Bros. and Western, and their stuff was all cleaned out by the three other movies that were shooting at the same time. So, I had no choice, but to make everything, which I did.”

That’s where Peter Sherayko and the Buckaroos came in.

Peter had created Caravans West Productions several years before the start of Tombstone. Manned by period-authentic re-enactors, Sherayko’s group helped out filmmakers by providing casting services, wardrobe, guns, ammunition, technical advice, horses and special effects. Each Buckaroo provided his own costume, be it cowboy, soldier or townsperson. Most were members of the Single Action Shooters Society and carried at least three weapons, including a rifle, shotgun and pistol. Excellent riders with period saddles and well-trained horses, they had to be able to handle their weapons with safety and skill. Sherayko himself owned a huge collection of artifacts and an extensive library of more than 5,000 Western books.

“I visited the set of Wildside in 1985 and noticed all the guns and rigs were wrong for the time frame,” Sherayko says. “When I mentioned that to Monte Laird, the technical advisor, he said, ‘A gun is a gun. The audience is stupid, they don’t know any better.’ That planted a seed in my head.

“I started around 1987 or ’88 [by] bringing my own [historically correct] guns into movies. [I told producers,] ‘Let me bring these guns in, I’m not going to charge you for them.’ I started doing that, and by 1990, word got out. I started renting stuff out, and people [began to call me] to do guns on the set. Act in a role, that was my ploy. Getting acting jobs by renting stuff. That’s how Caravans West was born.”

— Courtesy Billy Lang —

For Tombstone, Porro worked with Sherayko and the Buckaroos to farm out the wardrobe requirements. “Since this was a non-union film…I had most of the stuff manufactured in downtown LA [in the garment district],” Porro says. “I had a Filipino shirtmaker who worked out of her house, and she made all the shirts. Everything was being manufactured at all these different places. Nothing was made in a costume house. I think I may have rented, altogether, a rack of clothing. I did rent for the ladies’ background. I did some rentals in England and some derbies and suits.”

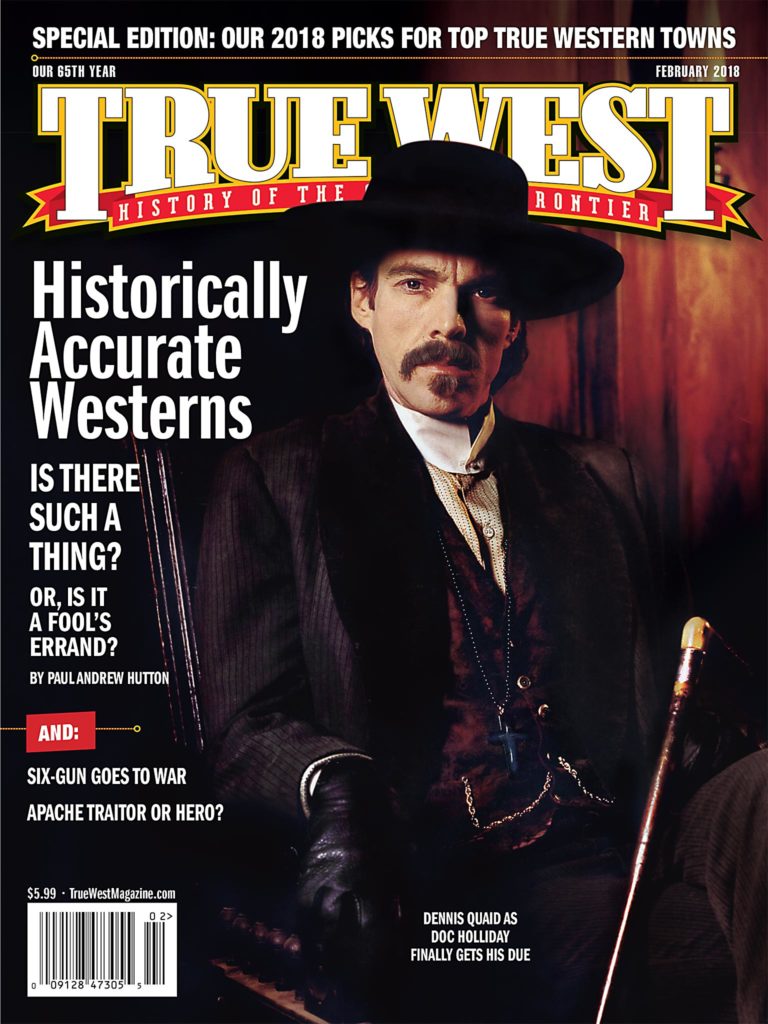

Despite his lack of “period” experience, Porro successfully translated historical research into reality. Jarre had made clear he was determined to avoid the stereotypical Western look. Tombstone would be the first Western film to be authentic in all departments.

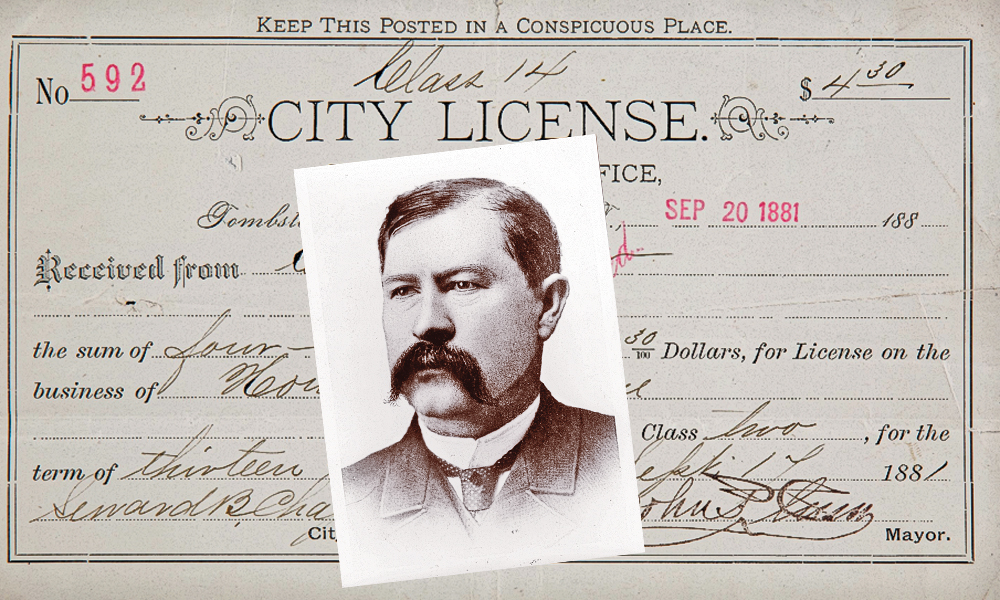

“Jarre wanted to capture the Victorian look of the cosmopolitan boomtown of 1881-1882,” Sherayko says. “He wanted a very clean, colorful, affluent look around Tombstone as was the fashion of the day.”

Sherayko became an incredible resource for Porro. “Joe would send his people out to my house,” Sherayko says. “I said, ‘Joe, come out. Go through my books, go through my stuff. Look at that.’ And then he designed everything. He designed all the outfits, but I had the people make stuff for him. He would buy the material, and they would make it.”

The first staff meeting between the director, writer and department heads set the tone and direction that Jarre wanted to take.

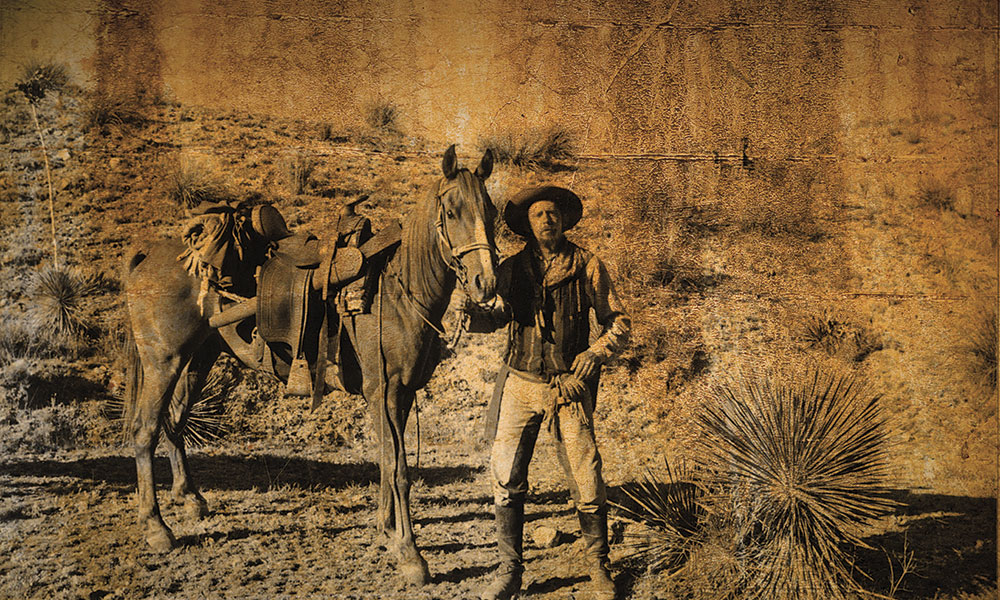

“[Kevin] said, ‘Peter, bring in the Buckaroos, let me see what these guys look like. I haven’t seen anything yet,’” Sherayko says. “Well, I put them in alphabetical order, and the first guy—there’s a famous photo of a guy from the Hash Knife cowboy outfit in northern Arizona in 1880. What [that first guy] did was re-create that guy’s outfit, and he modeled the picture in the same way that the original photo was done. He did it in sepia. So, I gave him the picture.

“Well, Kevin looked at the first picture and said, ‘That is an 1880s Arizona cowboy. That’s what I want the red-sash gang to look like! This is it. Joe, take a look at this picture.’ Joe looked at the picture and said, ‘Okay, fine,’ and then he looked at the pictures of the other guys I brought in.

“When the meeting was over, [Porro] came up to me and said, ‘What book did you get this picture out of?’ I said, ‘Joe, that’s not a picture from a book, that’s one of my Buckaroos I’m bringing in.’ He stopped, his jaw open, and he said, ‘Oh, my God. I can’t have the extras looking better than the principals.’ And I said, ‘We can help you.’”

A variety of suppliers fulfilled Porro’s requirements: Island Girl Clothes, using material supplied by Porro, manufactured roughly 300 shirts. Island Girl was the nickname of Lanier Clark, the wife of Logan, one of the Buckaroos. Stetson Hat Company provided 100 hats for the film.

“We gave [Stetson] an original of the period,” Porro says. “They copied it, they did the block, we did it in different colors. Just made a slew of them and then by shaping them and having different bands…each one [was given] a little bit of character.”

The Montana Boot Company supplied 20 pairs of stovepipe and Coffeyville boots, while R. Gang made a majority of the gun belts. The Tucson Opera Company made all the women’s costumes, including Dana Delany’s. Most of the men’s suits were made by a Korean Hollywood tailor, Mr. Oh.

Kurt Russell’s long coat was based on an authentic coat. “That coat exists, absolutely,” Porro says. “No one ever used it in a movie before. It was probably a little more full[er], and I might have thinned it out for him. That coat is in one of my tailor books, those giant tailor books with swatches from the 1870s. I have two tailor books from that period.

“You would go into a tailor shop, and they would have a book, and they would have pictures of the style. Then they would have fabrics, wools and stuff that you could pick from. That coat was in a tailor book of the period, and we had it copied.”

Today, Porro isn’t entirely satisfied with his results, saying, “It’s not 100-percent period, when I look at it now. My eye has changed. I look at it now…there was too much padding in the shoulders. That was my tailor. Another part of that was the help of the actor’s shape. Today, I would have had no shoulders pads at all. It would have been all much softer. But that’s really the only thing, otherwise the clothes were pretty accurate. I used a lot of clothing of the period, original pieces and had them copied. The only thing that bothers me now to look at it is the shoulders didn’t fit quite right.”

Although some claimed that Jarre added the red sashes as “gang colors” or to merely identify the outlaws, Porro says the sashes were period-correct. Period pants normally didn’t contain belt loops, and braces, galluses and suspenders always got in the way, so sashes often were used as belts on high-waisted trousers. They also protected fabric from gun oil.

“I don’t know where it’s written, but somewhere historically it says that they wore this red sash,” Porro says. “We had to make those. I had those made at the Opera company.”

Of course, Jarre could have been inspired to use red sashes because of his hero, “Wild Bill” Hickok. Jeff Morey says that Jarre got the idea from Tombstone resident John Pleasant Gray, as quoted by Paula Mitchell Marks, in And Die in the West: “Gray remembered [Billy] Leonard as ‘a man much above his fellow rustlers in intellect and education.’ Leonard performed a service for [Gray]…and received in payment a copy of a book chronicling the life of Wild Bill Hickok. The delighted Leonard gathered his fellow rustlers around ‘and then spent the rest of the day reading to them,’ with the result that Hickok was ‘the hero, henceforth, of the rustlers.’”

As Hickok wore a sash, so should the rustlers.

Porro designed all the outfits worn by the female lead, Dana Delaney, but even the rentals from England worn by some of the Tombstone wives passed muster.

“They were good, they were quite accurate,” Porro says. “They were just so much better quality than the few that were left in America.”

Porro, though, couldn’t manufacture everything. Old Tucson Studios in Tucson, Arizona, came to the rescue and met the designer’s requirements, providing moccasins, concho and beaded belts with knife holders, a vintage Prince Albert frock coat, vests, pants, robes and skirts, corsets, handbags, pinafores, long johns, socks, shirts, boots and sombreros.

If Old Tucson Studio had it, Porro rented it out, for anywhere from $1.00 to $5.00 each per day.

Film history buff John Farkis lives in Brighton, Michigan. He is the author of Not Thinkin’…Just Rememberin’: The Making of John Wayne’s The Alamo and Alamo Village: How a Texas Cattleman Brought Hollywood to the Old West. His next book, due out in Winter of 2018, will cover the making of Tombstone, just in time for the 25th anniversary.