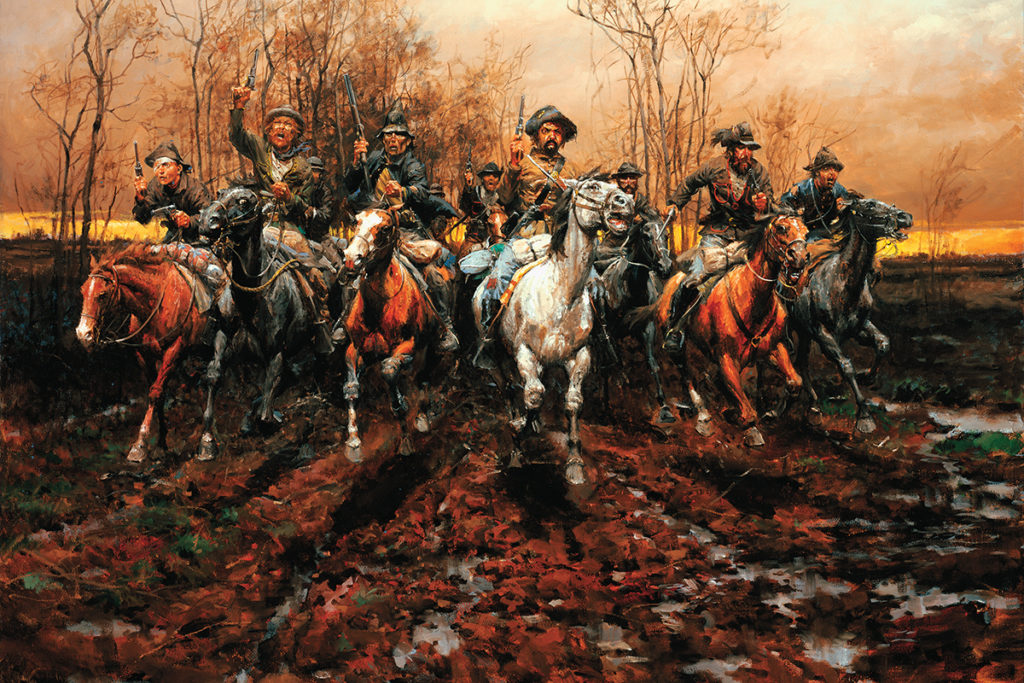

– Courtesy Andy Thomas Fine Art –

The wails, the babble of words, the murmuring of the crowd suddenly stopped as two young men appeared. They stepped past the body, approached a town marshal who stood close by, and offered to surrender. They had killed this man, one of them declared, and now they expected their reward. The lawman looked at them in astonishment. “My God,” he said, “do you mean to tell us that this is Jesse James?”

“Yes,” the pair replied in unison.

“Those who were standing near,” the reporter wrote, “drew in their breaths in silence at the thought of being so near Jesse James, even if he was dead.”

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted–

Robin Hood or Hooded Bandit?

Jesse James was not an inarticulate avenger for the poor; his popularity was driven by politics—politics based on wartime allegiances—and was rooted among former Confederates. Even his attacks on unpopular economic targets, the banks and the railroads, turn out on closer inspection to have had political resonances. He was, in fact, a major force in the attempt to create a Confederate identity for Missouri, a cultural and political offensive waged by the defeated rebels to undo the triumph of the Radical Republicans in the Civil War. His robberies, his murders, his letters to the newspapers, and his starring role in ex-Shelby Brigade cavalry Officer John N. Edwards’s Kansas City Times columns all played a part in the Confederate effort to achieve wartime goals by political means (to use historian Christopher Phillips’s neat reversal of Clausewitz’s dictum). Had Jesse James existed a century later, he would have been called a terrorist.

Terrorist? The term hardly fits with the traditional image of him as a Wild West outlaw, yippin’ and yellin’ and shooting it out with the county sheriff. But he saw himself as a Southerner, a Confederate, a vindicator of the rebel cause, and so he must be seen in the context of Southern “outlaws”—particularly the Klan and other highly political paramilitary forces. Even more important, he was not simply a puppet of John Edwards, but an active participant in the creation of his own legend. Edwards’s glorification of the bushwhacker bandits only began after the publicity-minded James rose to leadership and began to demand attention on his own. An avid student of current affairs, he sometimes outdid his editor friend in his public attacks on the Radical Republicans (to Edwards’s evident alarm). Was he a criminal? Yes. Was he in it for the money? Yes. Did he choose all his targets for political effect? No. He cannot be confused with the Red Brigades, the Tamil Tigers, Osama bin Laden or other groups that now shape our image of terrorism. But he was a political partisan in a hotly partisan era, and he eagerly offered himself up as a polarizing symbol of the Confederate project for postwar Missouri.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

There remains, of course, the straightforward power of his story. His is a tale of ambushes, gun battles, and daring raids, of narrow escapes, betrayals and revenge. Even his oddly alliterative name seems to have been conjured up by a novelist of overripe adventures. But an accurate understanding of his world can only add to the drama. When we look at his life in its proper setting—if we see it as did that crowd that held its breath around his body on Thirteenth and Lafayette—we see that the life of Jesse James was as significant as it was thrilling.

Clay County Plowboy to Missouri Marauder

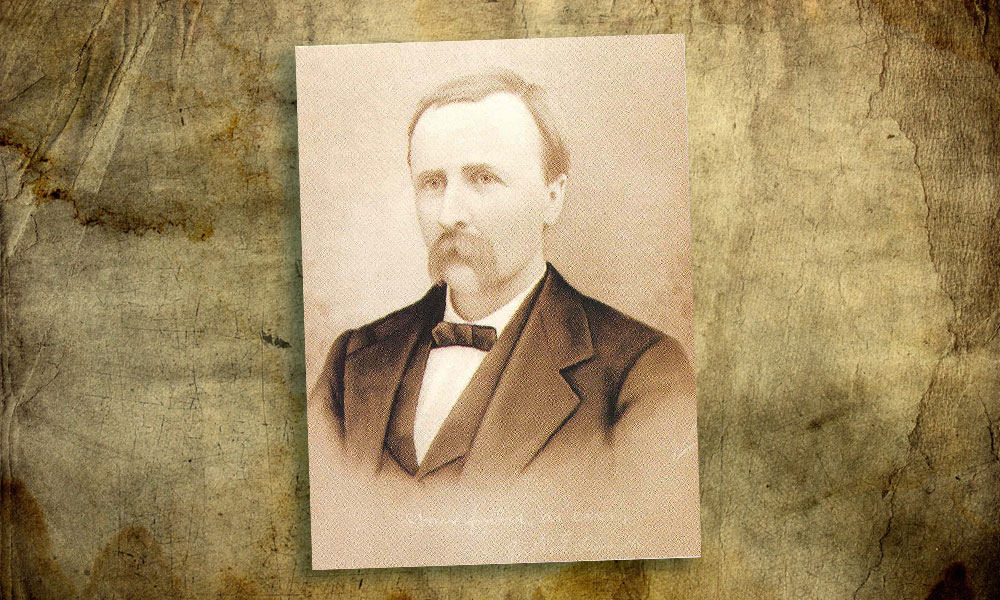

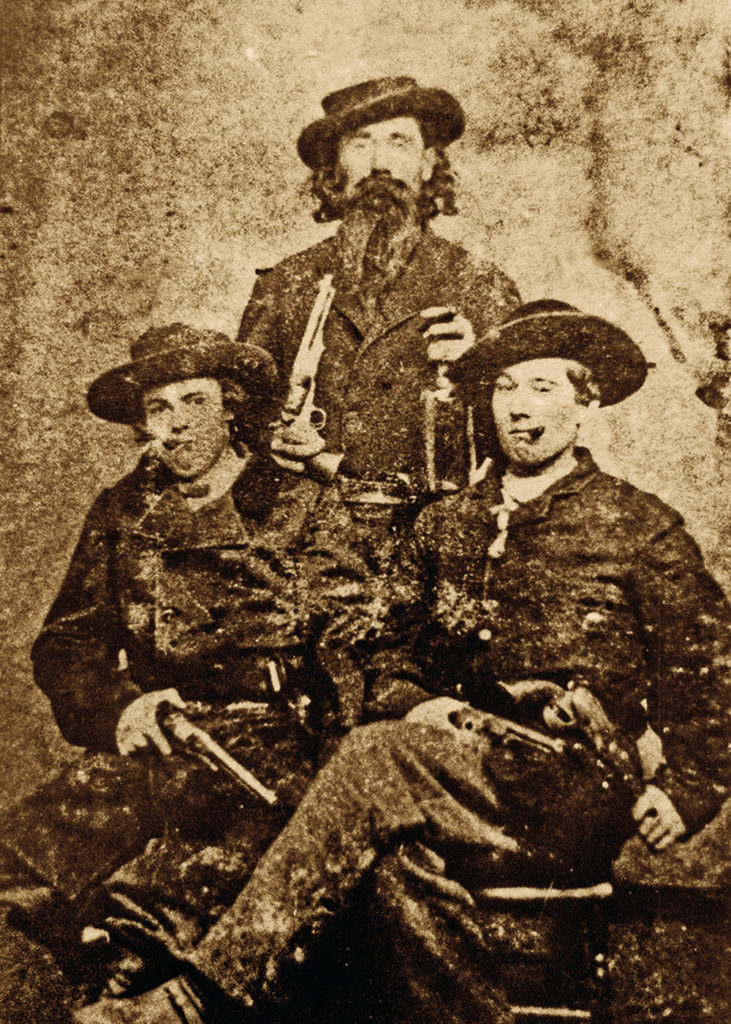

It was a savage set of men who returned with Frank that April [1864]. Already hardened by war, they had been blistered by butchery at Lawrence and debauchery in Texas. And Charles Fletcher Taylor, the man who led the small squad that crossed over to Clay County, was one of the hardest. Short, broad-shouldered, sporting a neatly trimmed mustache and beard, “Fletch” had fought with Quantrill from the beginning, scouting out Lawrence before the raid, murdering the innocent in its streets, then riding to Texas. But there he turned against his master, murdering a Confederate officer and resisting Quantrill’s attempt to arrest him. Now he fought (in the phrase of the times) “on his own hook.” Cantering beside him was an even smaller, even more vicious killer: “Little Archie” Clement, a gray-eyed 18-year-old from Johnson County. Barely five feet tall, he looked more like a jockey than a guerrilla. But he was already an experienced gunman, and he would soon win the lasting admiration of Frank’s little brother.

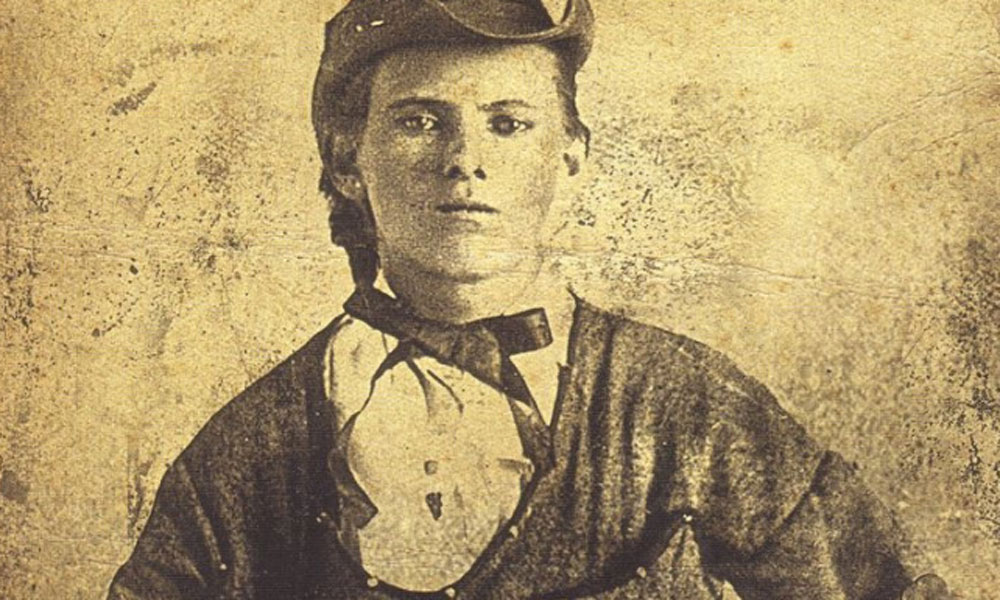

These were the men who brought 16-year-old Jesse James to manhood. A year after being dragged through the tobacco field by the Provisional militia, three years after Frank first enlisted in the State Guard, Jesse rode to war. Guided by Frank or another Clay County recruit in late May, he would have crept out at night and sneaked down hog trails to the rugged Fishing River, where Taylor and Clement lay hidden. “There seems to be something of the deathlike brooding over these camps,” wrote Sgt. Sherman Bodwell in his diary, after finding an abandoned bushwhacker bivouac. “Always hidden where hardly more than a horse track points the way, in heavy timber and creek bottoms, offal lying about, cooking utensils, cast-off clothing.”

Jesse would have seen a cluster of men gathered around the fire under an awning of low leaves and branches, cooking a meal, drying out socks, cleaning and loading weapons. A strong smell of horses, sweat and waste (human and animal) would have struck him, followed by the dense smoke of burning green wood with undertones of oiled leather and wet flannel. They were all young—some astonishingly young, like Jesse himself. “If you ever want to pick a company to do desperate work,” Frank later mused, “select young men from 17 to 21 years old. …Take our company and there has never been a more reckless lot of men. Only one or two were over 25. Most of them were under 21. Scarcely a dozen boasted a moustache.” Or, as another grizzled veteran put it, almost exactly a century after Jesse crept into that camp, “You’re going to learn that one of the most brutal things in the world is your average 19-year-old American boy.”

The Making of a Marauder

Now the ritual began. First was the matter of equipment. Either Zerelda or Charlotte sewed a guerrilla shirt for Jesse—a loose pullover with two deep breast pockets for percussion caps, powder charges and .36 caliber lead balls. Then he needed pistols, a horse and a saddle. The revolver was the primary weapon, its rapid rate of fire well suited to guerrilla ambushes. Before the war, Colt’s revolvers had been somewhat uncommon, even in Missouri, and they were hard to get legitimately after the conflict began. But the bushwhackers equipped themselves through smuggling, theft and plundering of the Union dead; so if Jesse didn’t have a set, one was given to him. As for horses, he would have been told to steal them.

This last lesson was the start of a much deeper, more lasting education. They were guerrillas. They were not engaged in a war that a colonel of the Army of the Potomac or a general of the Army of Northern Virginia could recognize. They had no lines, no objectives, no strategy, no command structure. Theirs was a purely tactical war, a war to inflict pain, to punish, to kill and destroy. Every barn and brook was a battlefield; every civilian, either an ally or a target. By stepping into that brooding, deathlike camp, Jesse James entered a race to find and kill as many enemies as he could.

Mayhem and Murder

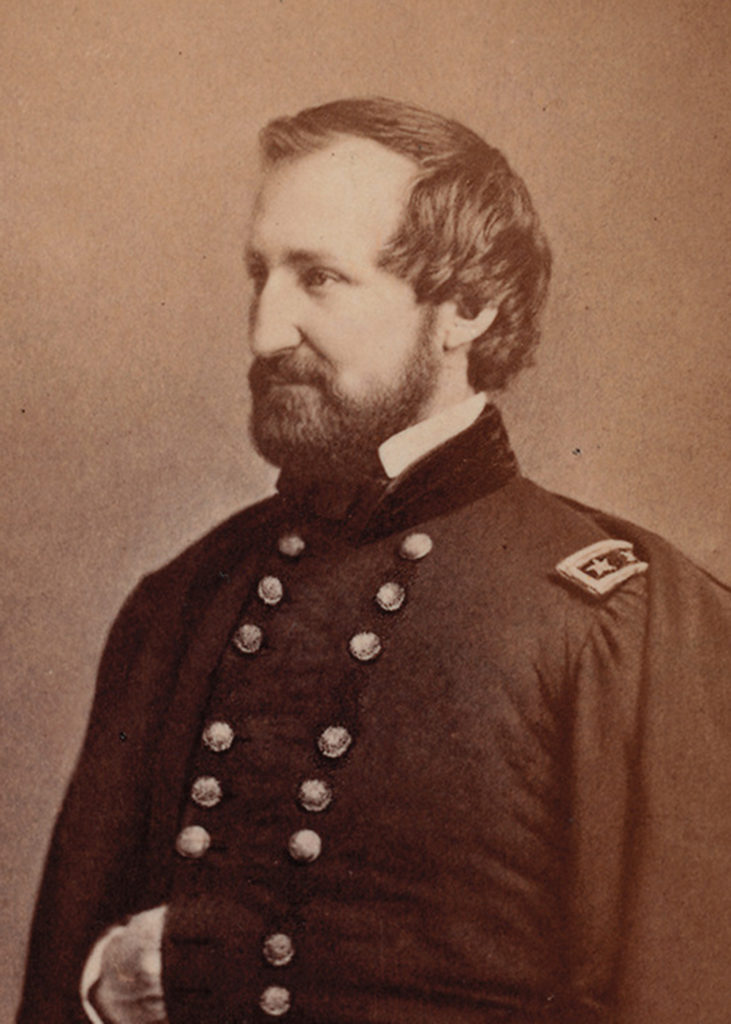

On April 29, 1864, Maj. Gen.William S. Rosecrans telegraphed an alert to Col. James H. Moss in Liberty. The guerrillas were returning, he warned, “to re-inaugurate the scenes of murder and robbery which have desolated your country during the past three years.” Rosecrans, humiliated by defeat at the battle of Chickamauga, had been shifted in January to command the Department of the Missouri, a strategic eddy far from the main channels of the war. The state might have been a backwater, but Rosecrans learned that its currents were swift and unpredictable. Accustomed to wielding brigades, divisions and corps as he marched toward objectives, he now had to weave a net out of slender companies, battalions and regiments as he waded into guerrilla waters. And no units threatened to unravel more quickly than Colonel Moss’s troublesome Paw Paws. “I expect from you and the Enrolled Militia under your command,” he wrote, “such a reception…as will amply vindicate you from all the charges of disloyalty which have been urged against you.” Moss assured Rosecrans that all would be well.

Brig. Gen. Clinton B. Fisk was not so certain. After a military reorganization in January, this stern and voluble officer had assumed command of the District of North Missouri, after serving in the southeastern corner of the state. Fisk had received his rank, in part, through connections in the northern branch of the Methodist Church, an avowedly abolitionist denomination; the savagery of the guerrilla war, however, had negated whatever Christian charity remained within him. Rather than rely on Moss, he shifted Capt. William B. Kemper and part of Company K 9th Cavalry Regiment, MSM to Liberty in early May 1864. “Clean out and kill every marauding, thieving villain you find,” he wrote to Kemper on May 15, adding, “Keep your eyes on the Paw Paws.”

The captain needed no instructions to that point: he intended to avoid Moss’s men at all costs as he pursued the bushwhackers. And the guerrillas were back—he could feel it. But every time he sent squads to scout the countryside, they came back emptyhanded. On May24, Kemper changed tactics. After nightfall, he ordered fifteen men to draw rations, mount their horses, and follow him into the country, where he deployed in ambush. After spending a day waiting for the enemy, he gathered his troopers out of hiding and moved on to another spot. Meanwhile, he sent out two spies; each night he rendezvoused with them to better plan his trap for the following day.

Across the Missouri River, the Second Colorado Cavalry employed the same tactics with devastating effect. Kemper, however, had fewer men and experienced opponents. Fletch Taylor and Archie Clement easily slipped past his ambushes to deliver a sharp reminder that there was no line between combatants and civilians. On June 1, they led their Clay County recruits (dressed in captured Union uniforms) to the farm of Bradley Bond. Gathering outside the front door, they asked to see the man of the house. When Bond stepped outside they shot him to death. The next day, they murdered Alvis Dagley in a field not far from the Samuel place, then trotted to his house and coldly told his widow.

Over the next few weeks, the gang killed at least eight Unionist civilians. “Men were slain before the eyes of their wives and children,” one resident wrote, “or else shot down without mercy by the roadside and their bodies left to fester and corrupt in the sun. Property was taken and destroyed on every hand, business of all kinds prostrated, values were unsettled, everything was disturbed.” They killed one slave “for fun,” and they looted as freely as the worst jayhawkers or militia.

The Keenest and Cleanest Fighter

Jesse James never attempted to distance himself from this slaughter; in later years, one of his closest friends boasted of how Jesse and Frank went alone to the home of a local Unionist, just after the death of Dagley, and murdered him outside his house. This, then, was his introduction to warfare: not as a gladiator in battle against a tyrannous foe, but as a member of a death squad, picking off neighbors one by one.

Of all the departures in Jesse James’s dramatic life, none would ever be so momentous—or portentous—as this one. …He had violence coaches on every side, from Zerelda (who explicitly praised the worst rebel atrocities) to his brother Frank. After he took to the brush, Taylor and Clement took over as his mentors; they mocked him for his boyish diffidence, nicknaming him “Dingus” after a euphemistic curse he once uttered. But once he joined in the killing, they gave him their respect. “Not to have any beard,” one of the deadliest guerrillas supposedly said of him, “he is the keenest and cleanest fighter in the command.” Jesse abandoned all civil norms, even the blunt- instrument morality of a slave-owning culture. He now belonged to a group that believed a man must murder for respect.

“Jesse James: Birth of a Killer” by T.J. Stiles is excerpted from his book Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (NY: Vintage Press, a division of Random House, Inc.).