After the Battle of Little Bighorn, the seven officers’ wives had an immortal bond.

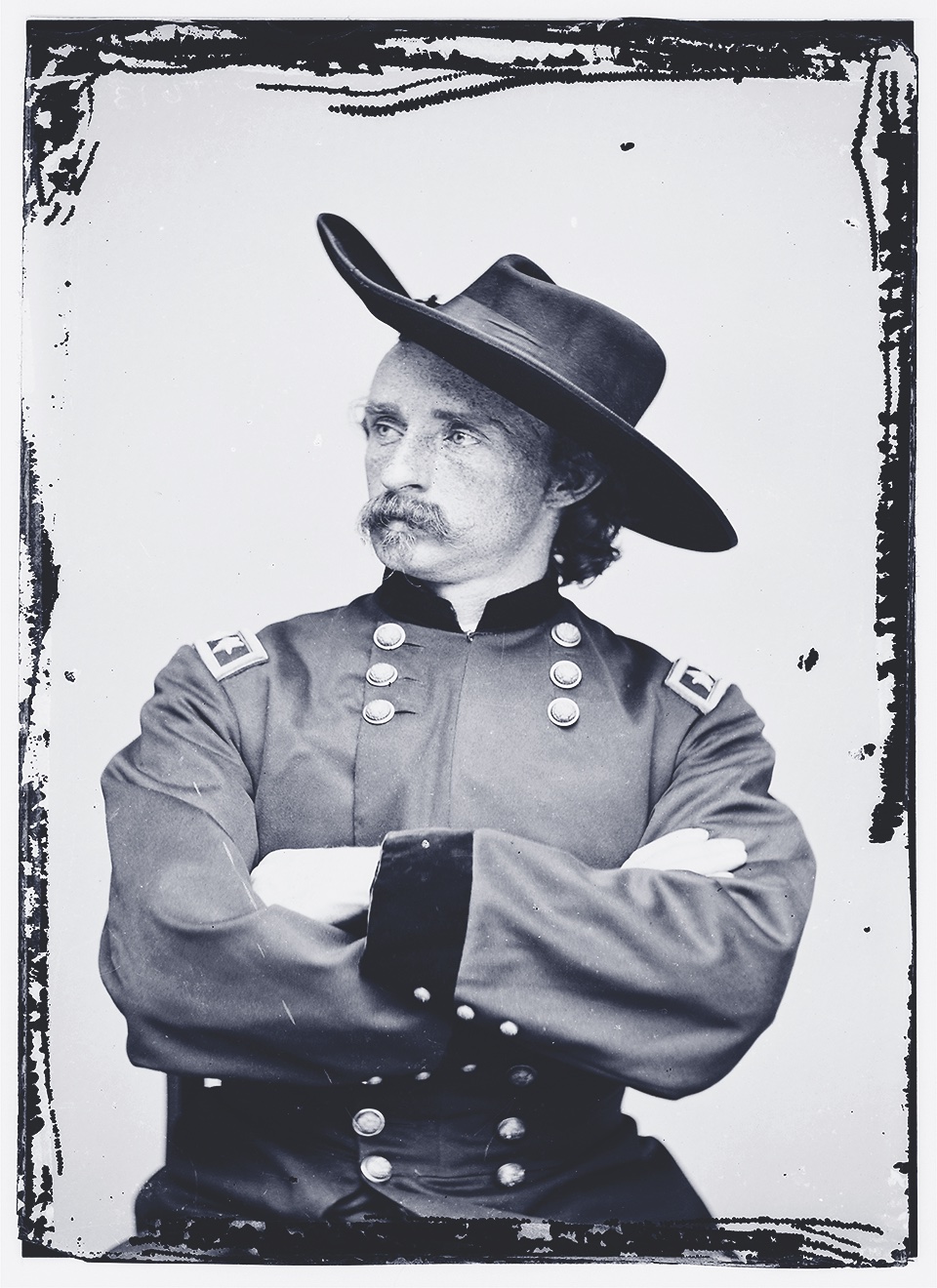

On July 29, 1876, Elizabeth Custer requested an audience with the widows and children of the enlisted men lost at the Battle of Little Bighorn. She struggled to maintain her composure while waiting for all to gather on the steps of her home. The sound of little ones laughing and talking drew her attention away from her own hurt. She greeted the children and their mothers as they slowly arrived with a smile; when everyone had assembled, she thanked them for their friendship and loyalty and wished them well in their lives beyond Fort Abraham Lincoln. Before saying goodbye, she presented each child with a picture of General Custer.

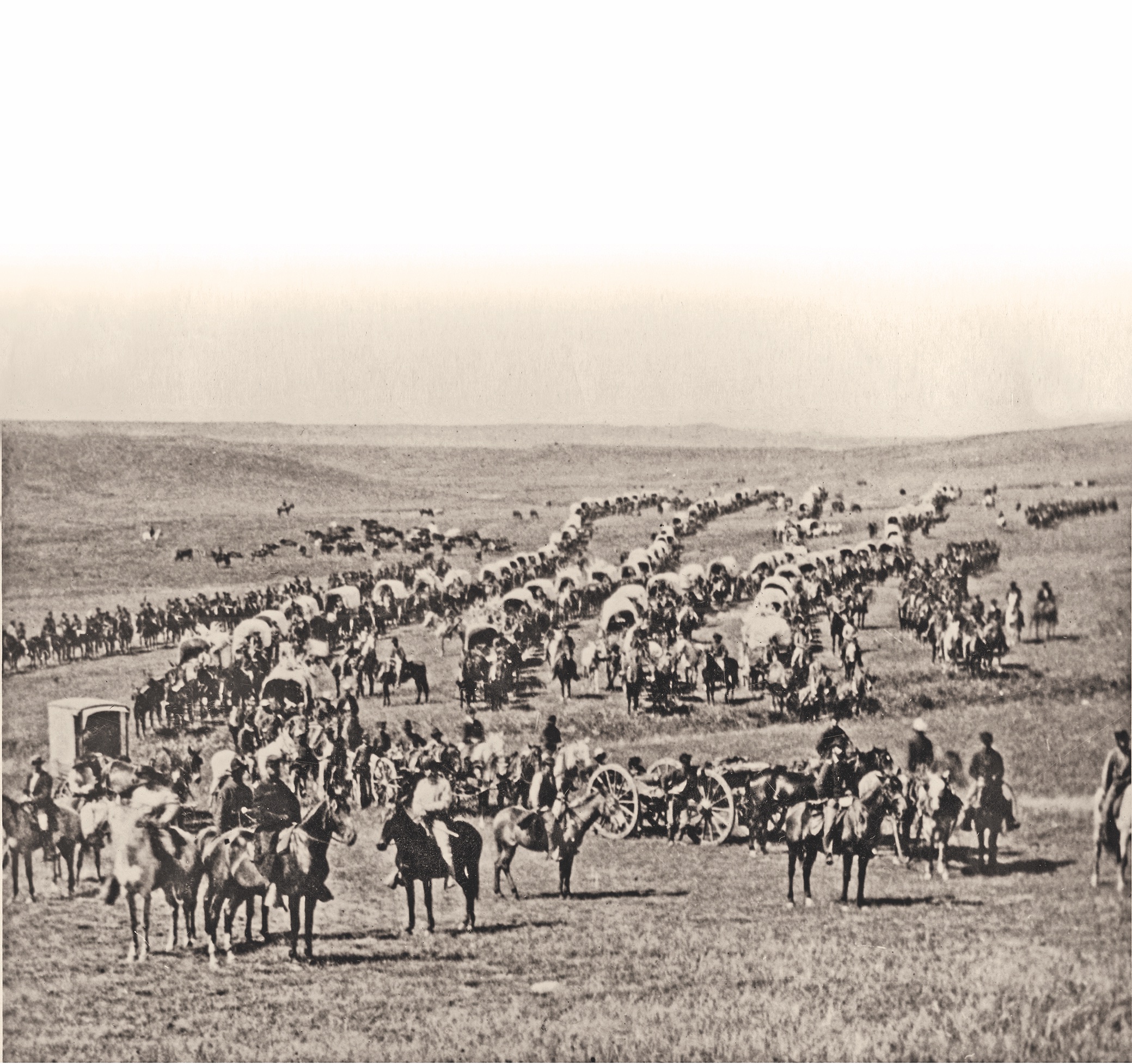

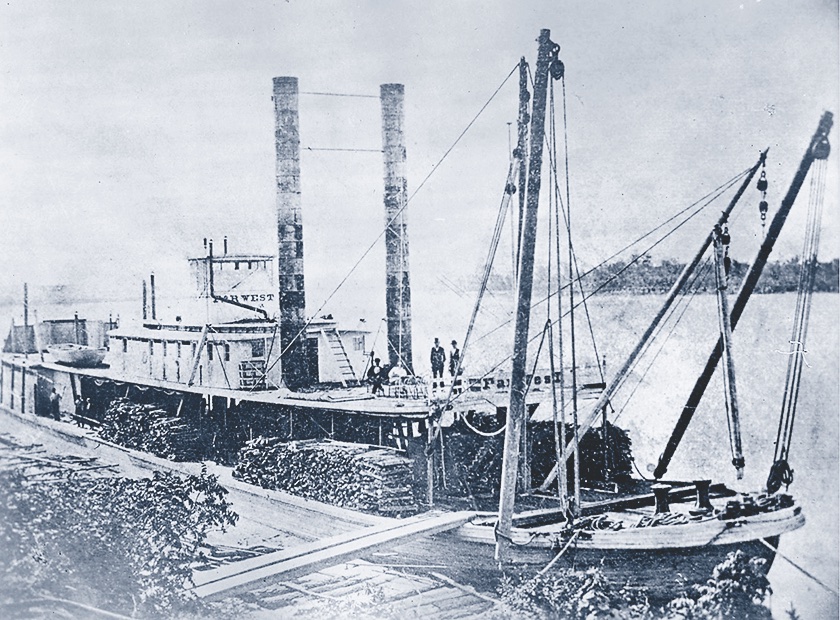

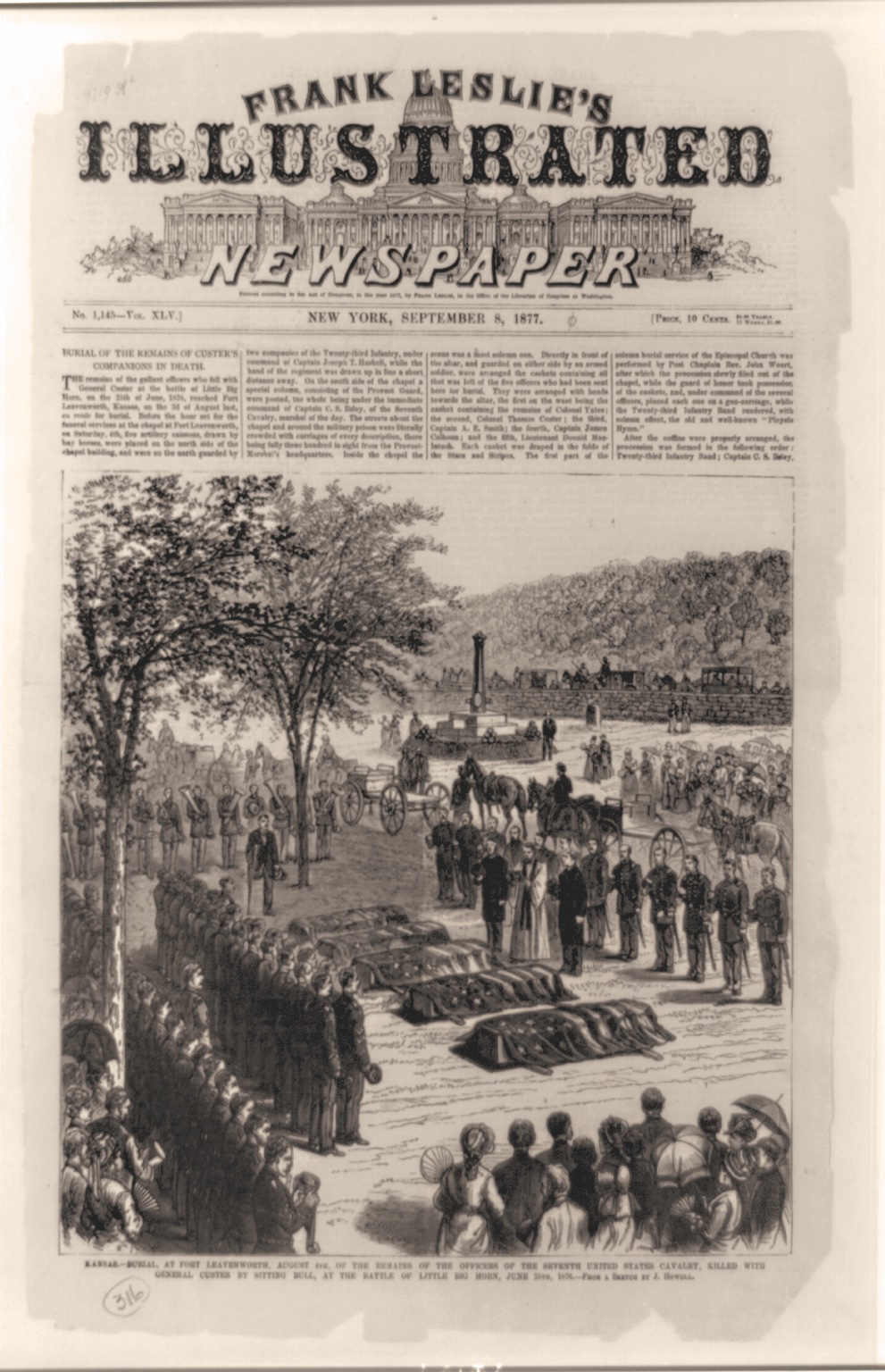

The following morning Elizabeth, Maggie Custer Calhoun, Nettie Bowen Smith, Annie Yates, and her three children, three-and-a-half-year-old George, twenty-two-month-old Bessie, and seven-month-old Milnor, Annie’s brother, Richard Roberts (a civilian herder and part-time newspaper correspondent), and David Reed (Elizabeth’s brother-in-law and father of Henry Reed) traveled to Bismarck, in the Dakota Territory via carriage and steamboat. All the ladies were dressed in black, and all but Elizabeth were seen crying as the steamship carried the sorrowful party down the river. In Bismarck, the widows were met by Col. J. W. Raymond and were guests overnight in his home. The next morning, they boarded a special railroad car to begin the long journey back to Monroe.

The travels of the “widowed ones,” a name given the women by the editor of the Minneapolis, Minnesota, Star Tribune, were covered extensively by newspapers across the country. Reporters eager to get a glimpse of the forlorn women, especially Elizabeth, gathered at the train’s first stop in St. Paul. They noted they were able to see the widows through the window of the vehicle. “It is a tragic sight,” an article in the August 4, 1876, edition of The Findlay Jeffersonian read. “It is now thought that Mrs. Custer will not long survive her husband. Her condition is a critical one, and her death may be looked for at any time. The bullet that pierced the brave Custer was also the death wound for his loving wife.”

Before the train pulled out of the station in St. Paul the following day, another passenger boarded. Reverend Richard Wainwright had been asked by H. A. Town, the superintendent of the Northern Pacific Railroad, the railroad that provided the special car for the widows, to ride along with them and provide any comfort needed. Maggie Calhoun, in particular, was sick with grief, and nothing anyone did relieved her anguish for a single moment. Reverend Wainwright agreed to accompany the group until they reached their destination.

When the train reached Fargo, where the passengers were to disembark for the evening, they found a large, respectful crowd waiting for them. All was quiet as the widows stepped off the train and walked by the solemn onlookers. Men removed their hats, and women and children lowered their heads. Stooped over and ashen-faced, Elizabeth led the way. She moved slowly as though the weight of overwhelming sadness had become almost too much to carry. As the last of the stricken widows passed the sea of townspeople, several citizens could be heard crying. Even the men felt sorry for the unfortunate souls. They backhanded tears streaming down their faces or wiped their eyes with handkerchiefs.

From Fargo, the mourners boarded the Chicago and Northwestern to continue their trip into Illinois. They arrived in Chicago on August 3. From the train station, the women were escorted by Col. William Moore to a hotel known as the Palmer House. General Phil Sheridan had ordered the colonel to be there to welcome the widows to the city and to offer any assistance they might need. Newspaper accounts of the widows’ visit reported that, with the exception of Annie Yates, the distressed ladies were “very much prostrated.” Had Annie not needed to watch over her three children, her head would have been down as well. Porter Palmer, owner of the Palmer House, and his wife, Bertha, offered their own private rooms to the widows and refused to charge them for their stay. The Palmers were so moved by the tragic event that brought about the loss of human life and the dignified manner in which the women comported themselves, they decided to start a fund to benefit the officers’ wives. The Palmers contributed the first $250.

Five days after leaving Fort Abraham Lincoln, Elizabeth and the other widows reached Monroe. When Elizabeth stepped off the train, all efforts to control her feelings abandoned her, and she burst into tears. Perhaps it was the relief of finally making it home after experiencing unimaginable devastation. Maybe it was the memory of lost loves in such a familiar setting, or a combination of both. She had held herself strong for the others, but at that moment simply could not hold back the emotion.

Reverend Erasmus J. Boyd, longtime president of the Monroe Seminary and Elizabeth’s teacher for many years, met the widows at the depot. When Elizabeth saw Reverend Boyd, she flung herself into his arms, weeping and then fainting. The reverend and other members of the church revived her, then led her to the clergyman’s carriage.

Maggie followed Elizabeth out of the train and was so overcome with emotion she could not make it down the steps on her own. David Reed and Richard Roberts helped her to the reverend’s carriage and seated her beside Elizabeth. Annie Yates, her children, and Emma Reed exited the train last. Nettie Smith stayed on board. The trip would not end for her until she reached her parents’ home in Herkimer, New York.

Former 1st Lt. Frank Commagere was present at the station when the widows’ train stopped in Monroe. Commagere was a reporter who had been asked to cover the arrival of the bereaved for the Toledo Journal. In 1866, Commagere had been assigned to the 7th Cavalry under then Lt. Col. George Custer at Fort Riley, Kansas. During his time there, he had met Elizabeth and grown fond of both Mr. and Mrs. Custer. The editor of the Toledo Journal had tasked Commagere with interviewing the widows. Given his prior association with Elizabeth and witnessing the low state of health she was in, Commagere refused to question her or any of the other afflicted women.

“[I] contented myself with the barren formality of a card par condolence,” he wrote in the article dated August 5, 1876. “Mrs. Calhoun, the sister of General George A. and Colonel Tom Custer, and widow of a third dead hero, Lieutenant Calhoun, is with Mrs. Custer, staying at General Custer’s homestead, where the father and mother of the dead sabreur have long kept the home fire burning.

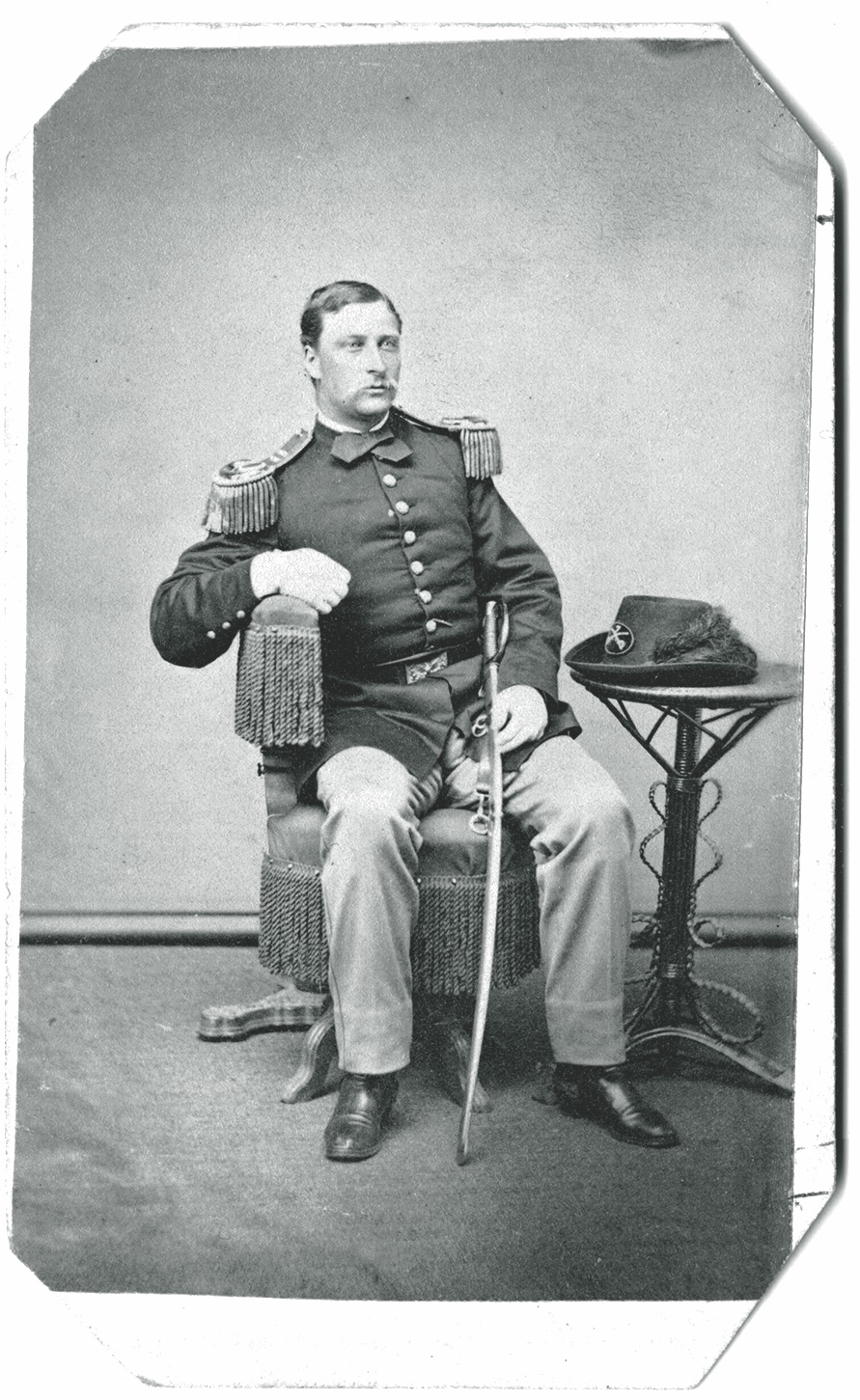

“Mrs. Yates, the widow of Geo. A. Yates, who died in the massacre of June at the head of his company, is the daughter of Mr. W. Milner Roberts, engineer in chief of the Northern Pacific Railway, and a granddaughter of the late Chief Justice Gibson of Pennsylvania. [S]he had decided to establish her residence here, so that she may be near her loved companions in suffering and has already rented a beautiful cottage on Monroe Street opposite the residence of David Reed.”

The widows spent the days after their arrival in Monroe visiting with family and close friends. They rejected unknown callers who felt compelled to stop by and pay their respects. Elizabeth warned Annie and Maggie against talking to strangers pretending to be concerned for their welfare, as some might be newspaper reporters hoping to get information about Custer’s command by capitalizing on their vulnerability. Some publications continued to insinuate that General Custer’s ego and recklessness contributed to the outcome at Little Bighorn. The widows continued to be annoyed by the rumors. All found solace in reading the letters of condolence that continued to pour in from all parts of the country.

Major General George B. McClellan, whom Custer served under during the Civil War, wrote to Elizabeth in early August to offer words of comfort. “As a man, I mourn in your noble husband’s death the loss of a warm, unselfish and devoted friend. As a soldier and a citizen, I lament the death of one of the most brilliant ornaments of the service and the nation, a most able and gallant soldier, a pure and noble gentleman. At my time of life, I can ill afford to lose such a soldier and such a citizen. It is some consolation to me, I cannot doubt it is to you, that he died as he had lived, a gallant gentleman, a true hero, fighting unflinchingly to the last desperate odds…

“My wife joins me in heartfelt sympathy… May God give you strength to bear under your burden of sorrow, teach you to look with calm resignation to the day when He permits you to rejoin him. Always your sincere friend, George B. McClellan.”

In a letter dated September 12, 1876, George G. Roberts, Annie Yates’ brother, wrote to express his sorrow and share what life was like at Fort Abraham Lincoln since Elizabeth and the other widows and children were gone.

“My Dear Mrs. Custer, Mrs. Godfrey will write to Annie today, so I will mail a short letter to you, my kind friend. My thoughts are often with you and all the dear ones in Monroe. I look forward to my visit. [I] expect to fill Annie with so much pleasure, yet I dare not say for a reliable fact that I can get a leave.

“No news in the post. Did I mention the new clubroom at the end of the lane? …It is almost finished.

“The weather for ten days or more has been of the dark, rainy, … unagreeable kind, yet I have not allowed it to tolerate any depressing feelings in me.

“How can I say thank you to you at such a distance when I feel a great large thank you always in my heart to you on the interest you have shown in my sister? I hope Maggie is doing better so that Annie can have more of her company. Annie can always tell you and Maggie anything that is in my letter.

“Larry Milnore is sick. I hope he will be well again.

“With kindness to you and Miss Emma Reed. Love to Maggie, hello to Annie and the children. You are all sorely missed. George Roberts.”

Neither Elizabeth, Maggie, nor Annie was in any state to respond to any letters. They were brokenhearted and lacked the will to do much more than make it through to the next day. Maggie’s grief had affected her physical health. She suffered with migraines and vertigo and spent most of her time in a quiet, dark room, seldom moving from her bed. Annie kept herself busy with her children and tending to her home. Nights were especially hard. She shared with Elizabeth that she often imagined hearing George’s voice calling her. She had trouble sleeping, and when she did sleep, she dreamed she was back at Fort Abraham Lincoln waiting for her husband to return. Elizabeth transformed the room she occupied at her in-law’s home into a shrine to Custer. His desk with his books, papers and journal was set up exactly as it looked at their quarters at Fort Abraham Lincoln. She hung the stuffed heads of the elk and deer Custer had hunted over the desk with his favorite pictures beside them. His uniforms were placed in the wardrobe next to her dresses.

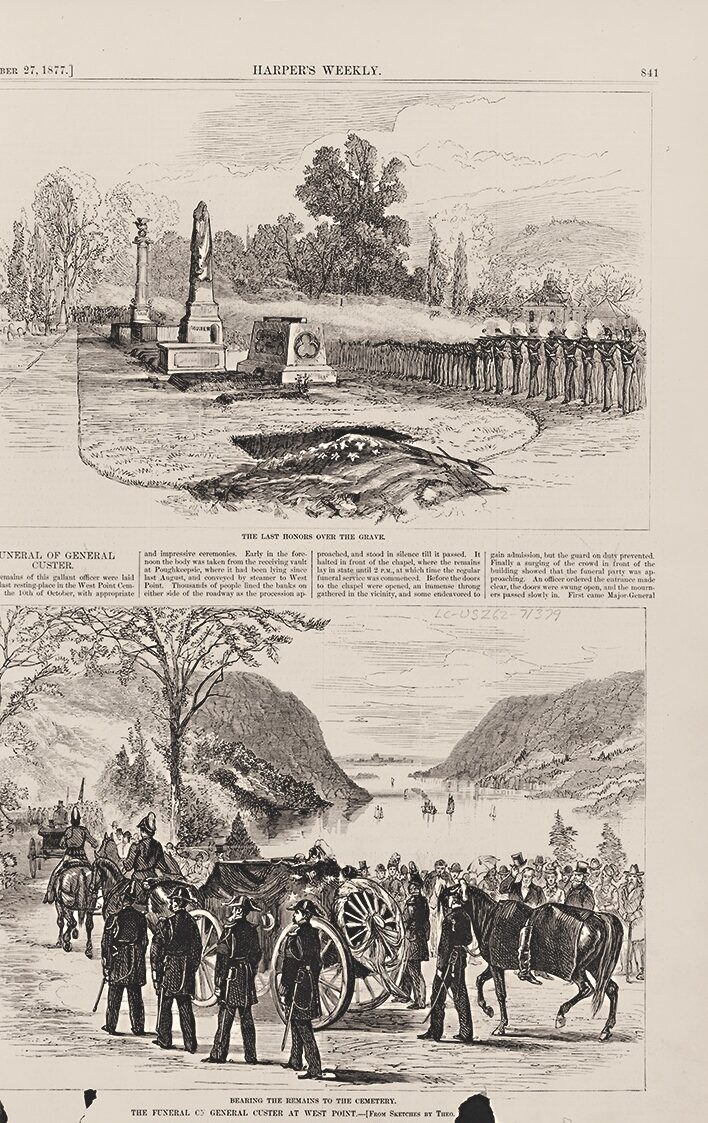

Courtesy Library of Congress