Our readers remind us of the variables and vagaries of historic truths, “well-established” facts, headlines and historical photographs.

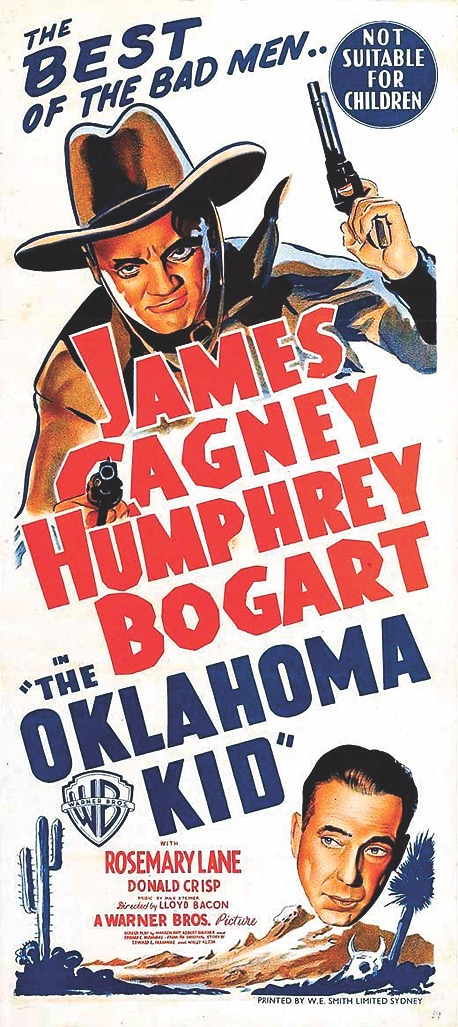

The Oklahoma Kid

Enjoyed the article, photos and illustrations on Bat Masterson [TW, June 2022]. I have heard that actor James Cagney, after his success in Ragtime (1981) was signed to portray Marshal/sportswriter Masterson in his later years in a film tentatively titled The Eagle in New York. Unfortunately, I’ve never been able to verify this or find out how far the production had progressed. Was there a synopsis, a script, any pre-production photography? As a cartoonist I’ve worked on Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy but have learned nothing of the sleuth’s detecting skill. Can you and your deer stalkers find out any details?

—Richard Pietrzyk, Westmont, Illinois

Thanks, Richard. We asked our Western Films editor Henry C. Parke for an answer to your query. Here is his answer:

“Although long identified with gangster films and musicals, actor James Cagney loved Westerns. As he noted in Cagney by Cagney, “I am, have been, and always will be, a man for horses.”

His first Western, in 1939, started out as a biopic of Kit Carson. But by the time Warner Brothers finished meddling with the script, The Oklahoma Kid “…had as much to do with actual history as the Katzenjammer Kids.” In 1981, Cagney was announced for a Western role worthy of his talent: director Irvin Passer was set to direct The Eagle of Broadway, starring Cagney as lawman-turned-New York sportswriter Bat Masterson, co-starring William Hurt as Damon Runyan, the author whose character Sky Masterson in his short story “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown” was based on Bat Masterson. The story became the basis of the musical Guys and Dolls. But The Eagle of Broadway never happened.”

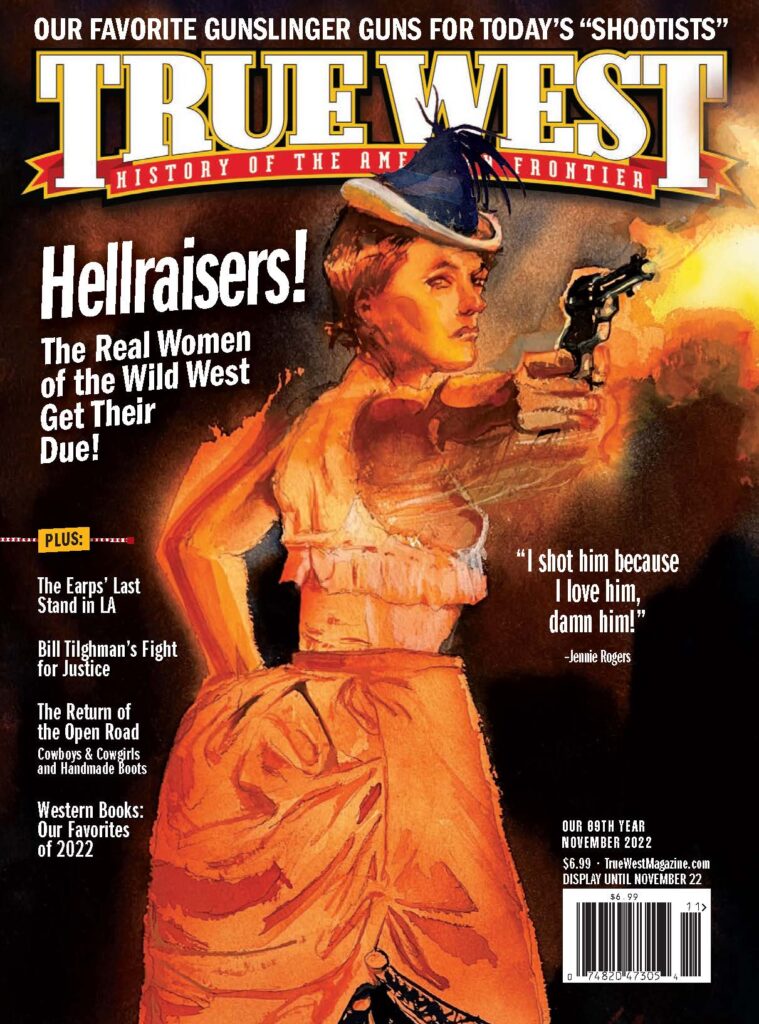

Women of the West

Just finished reading my September issue of True West magazine. I read it from cover to cover, and I want to say thank you thank you thank you! I’ve been waiting a long time for you to put out an issue that is about nothing but the women of the West. I usually share my magazine with other family members, but this one I will keep for myself to reread again and again.

—Constance Moran, Platte City, Missouri

Home on the Range

I opened my September issue of True West to “Opening Shot,” “Home on the Range” and could not take my eyes off it. There stands the Moore family in the foreground out on the open prairie in 1886. Then to the left stands their home built as homes have been built since the start of civilization, with whatever materials one can find, in this case sod, with some precious timbers and some surprisingly large windows. Even so, the house is built simply with materials anyone in the world going back to old Adam would recognize.

Then what appears to the right is state-of-the-art, a prim new Challenge Company windmill hauled in by wagon from Batavia, Illinois, and behind it a horse-drawn wooden-wheeled hay rake. These people know where to apply their resources and money to survive. Judging from their own appearance and their livestock, they are doing just fine.

—Rex Rideout, Conifer, Colorado

Who Killed Crazy Horse?

In True West’s July/August 2022 issue, the article “Crazy Horse’s Final Vision” written by Mark Lee Gardner failed to name the individual (sentry) who actually “swiftly guided the sharp point of his bayonet” into Crazy Horse, which resulted in his death. Why did he not name the sentry?

—Dennis Brugos, El Cajon, California

Great question, Dennis. We should have inserted the name into the excerpt. According to Gardner’s endnotes, “[t]he soldier who bayoneted Crazy Horse has been identified as William Gentles as cited in Paul L. Hedren’s “Who Killed Crazy Horse: A Historiographical Review and Affirmation,” Nebraska History Magazine 101 (Spring 2020): 2–17. —SR

Corrections:

In the September 2022 issue, on page 86, the reference to Desert Caballeros Western Art Museum’s annual event celebrating women artists of the West should have read “Cowgirl Up!,” not “Cowboy Up!”

In the October 2022 issue, on page 70, the painting Buffalo Chase Surround by the Hidatsa by George Catlin should have been credited to the Smithsonian Institution rather than the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.