The Sioux Leader’s Final Flight to Freedom

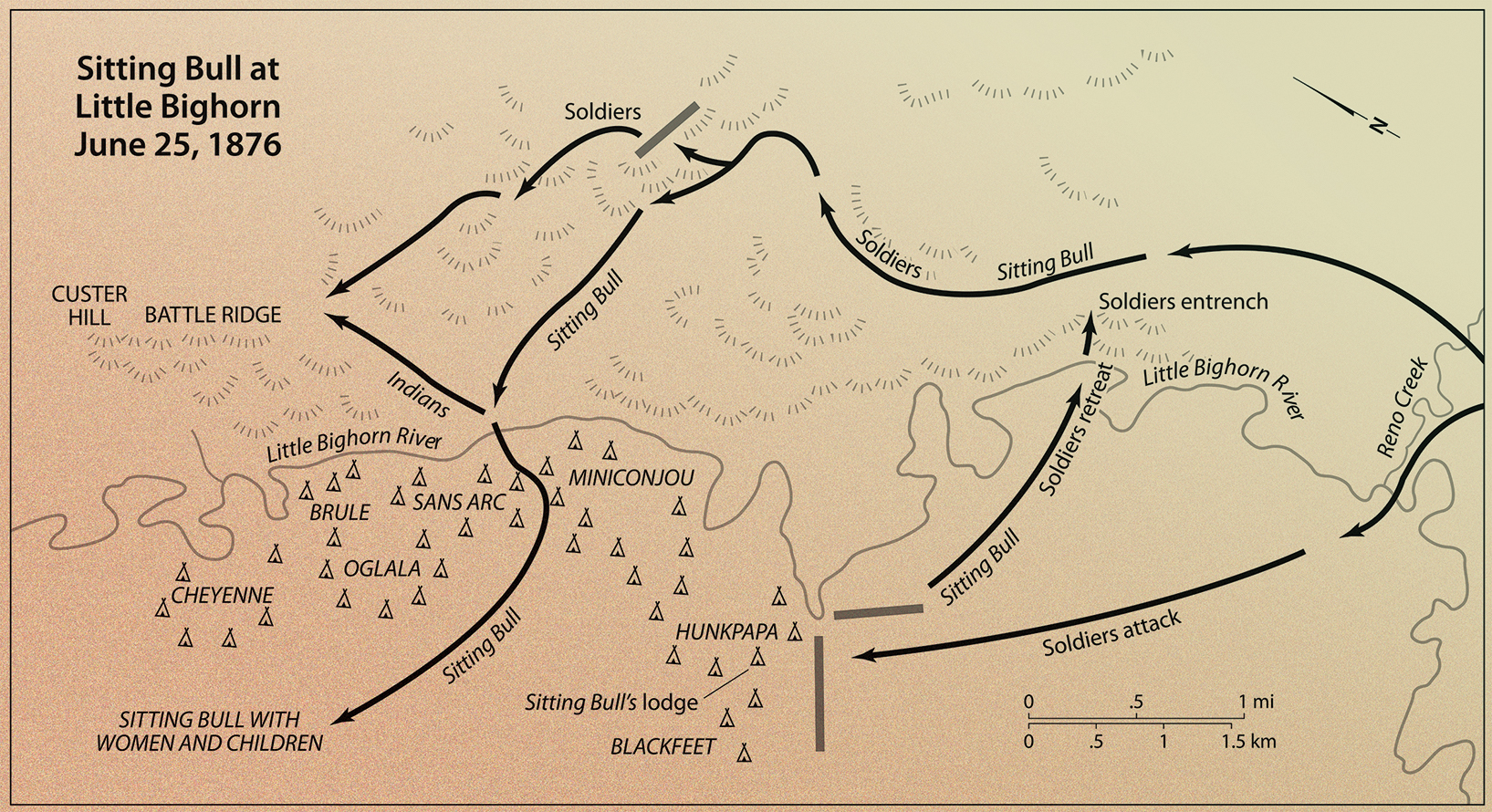

Sunday, June 25, 1876, was a clear, hot, sunny day in the valley of Montana’s Greasy Grass River, which the white man’s maps labeled the Little Bighorn. Six tribal circles of Lakotas and one of Northern Cheyennes, the coalition of winter roamers, sprawled for nearly three miles down the narrow valley, rimmed on the east by the snow-fed river. The Hunkpapas occupied the extreme upper end of the village, the Cheyennes the lower. In between rose the lodges of Blackfeet, Miniconjou, Sans Arc, Oglala and Brule. It was an unusually large village: 7,000 people, 2,000 warriors, housed in thousands of tipis and wickyups. In the past few days, Indians arriving from the agencies had swollen the village.

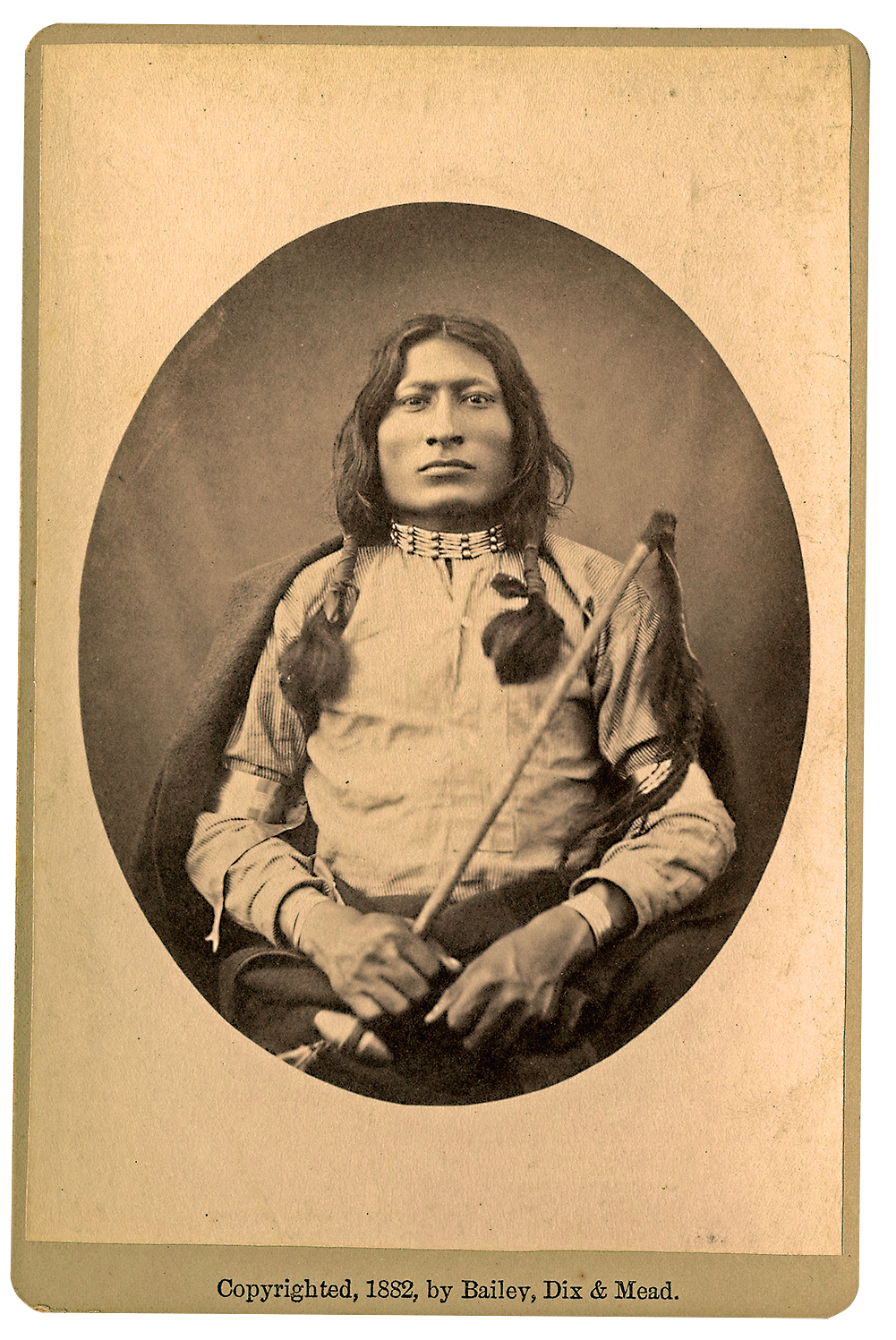

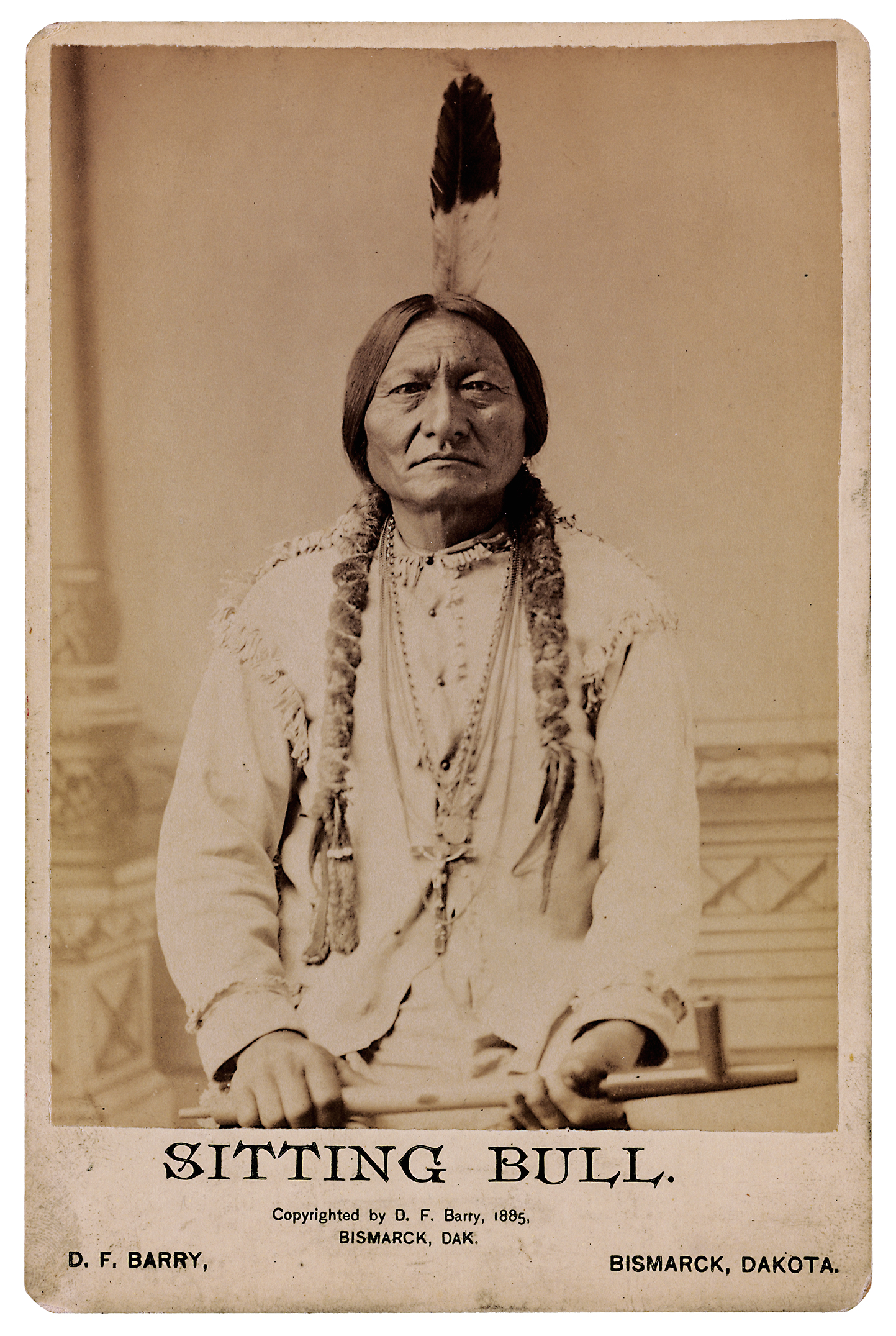

Sitting Bull’s lodge, on the southern edge of the Hunkpapa circle, sheltered 12 people besides the chief: two wives, his mother, two teenage daughters, three sons, two stepsons, his sister and the brother of his two wives. He treasured his family.

On this hot summer day, some of the men rode up to the bench-land west of the valley to tend their grazing pony herds. After a night of dancing and feasting, others dozed in their tipis or beneath the tall cottonwood trees shading the riverbank. Children played in the cool waters of the stream. Women dug for wild roots.

In the middle of the afternoon, a current of anxiety ran through the village, disturbing the peaceful scene. Shortly, heralds rode through each circle. “They are charging, the chargers are coming!” they cried. They were coming, and they were soon within sight of Sitting Bull’s lodge. “I heard a terrific volley of carbines,” recalled Moving Robe Woman. “The bullets shattered the tipi poles. Women and children were running away from the gunfire.” In the tumult, Moving Robe Woman recalled, “I heard old men and women singing death songs for their warriors who were now ready to attack the soldiers.” One Bull and White Bull galloped down from the bench to help their uncle prepare for battle. Old man chiefs were not supposed to fight, but he had to defend himself and his family. Astride a large black horse, brandishing a Winchester rifle, he hurried among warriors pouring from their tipis. “Brave up, boys, it will be a hard time. Brave up!” White Bull shouted.

But the “chargers” quit charging. They got off their horses and lay on the ground firing at the Hunkpapa tipis. Sitting Bull dismounted and joined others, including the venerated chief Four Horns, in a shallow draw from which to shoot back. White Bull called this “standstill shooting.”

Soon warriors from the other tribal circles began reaching the scene, many following the indomitable Oglala, Crazy Horse. The standstill shooting ended.

Crazy Horse and the arriving warriors drove the soldiers into timber enclosed by a bend in the river. Now on the defensive, the troopers fought back, though ineffectively. In about twenty minutes they mounted and burst from the timber, racing across the open valley toward a line of high bluffs on the other side of the river, every man for himself. Warriors rode among them, striking them down as they sought to save themselves. They jumped into and crossed the river, then climbed the bluffs to the top. They had lost 30 killed and 13 wounded.

Sitting Bull had not ridden in this rout of the soldiers. As long as they remained in the valley, he fired his Winchester at them and encouraged his young men to fight. After the soldiers had reached the top of the bluffs, he rode about the valley examining the carnage, then crossed the river and climbed one of the ravines scouring the bluffs. At the top, soldiers had formed into a defensive circle and were exchanging fire with Indians scaling the heights. One Bull recalled that his uncle “was back on the hill sort of directing things, though he himself did not go into the fight at all”—appropriate behavior for an old man chief. He even remarked to One Bull that the warriors should let the soldiers go back home and tell the whites what had occurred on these bluffs.

– Bill Nelson Cartography, Courtesy University of Nebraska Press –

But there were still more soldiers to fight. They had been glimpsed downstream, opposite the lower end of the village. “The word passed among the Indians like a whirlwind,” said Red Horse, “and they all started to attack this new party, leaving the troops on the hill.”

Accompanied by One Bull, Sitting Bull joined the other warriors hastening north along the ridgetops. Soon they spotted the new threat: many soldiers already fighting against converging warriors. Instead of joining the fight, Sitting Bull left One Bull and worked his way down a broad coulee to the river, splashed across, and rode to where the women and children had gathered beyond the Cheyenne circle. He saw his duty as helping to protect the women and children, rather than exposing himself in the battle that he could see developing on a high ridge across the river.

Smoke and dust obscured the details of the fighting rolling along the crest of the ridge. Within an hour Sitting Bull learned the outcome. The warriors had annihilated the entire contingent of soldiers, including “Long Hair” Custer. Sitting Bull’s prayers had been answered and his prophecy validated by the greatest triumph in the history of his people.

The soldiers who had first attacked the village remained on the bluffs four miles to the south. Warriors rode in that direction to resume the battle. They found that more soldiers had arrived to strengthen the ones who had retreated from the valley. They had scooped out shallow rifle pits and fired at the returning warriors. Sitting Bull and One Bull took station on a high ridge overlooking the defenders and fired shots at them. Shortly, however, Sitting Bull went back to his lodge in the valley. Here he witnessed the sad spectacle of dead and wounded warriors draped over the backs of horses, borne down from the heights. The battle that had killed so many soldiers had also brought grief to families in the valley.

The fight for the hilltop resumed early the next morning. Sitting Bull remained in his lodge until noon, when he climbed the bluffs. Again, he believed the fighting should end: “Let them go now so some can go home and spread the news. I just saw more soldiers coming.”

– Nelson A. Miles, Upper Left, Courtesy

Library of Congress; Miles, above right,

Courtesy True West Archives –

More soldiers were coming, south up the valley. People in the village discovered their approach and at once began to dismantle their tipis and pack for a hasty flight. Sitting Bull returned to his lodge and with his family joined the procession up the valley, away from the oncoming soldiers.

The battle was over, but the war wasn’t. The white people were furious. They could hardly believe that Long Hair Custer and 225 men of the 7th Cavalry regiment had met with such a catastrophe. Even the generals were at first skeptical. When the truth dawned on the nation, Sitting Bull personified the calamity. Fresh soldiers poured up the Yellowstone to join with those already in the field. Revenge was the watchword. As they pursued the conquest of the Lakotas, one name loomed above all other chiefs’: Sitting Bull. He was the man to get.

He was not easy to get. The great Lakota coalition split into several components, some bearing south, others north. Sitting Bull chose the latter.

Word that buffalo ranged the plains north of the Yellowstone lured Sitting Bull north and across the Yellowstone, which he forded on October 10, 1876. Miniconjous and Sans Arcs accompanied the Hunkpapas. The next day they spotted a large encampment of Army supply wagons opposite the mouth of Glendive Creek. Warriors attacked but were driven off by the soldiers. Afterward the wagons formed into a train and began moving up the river. On October 15 and 16, One Bull and fellow warriors swarmed around them, only to be thwarted again by “walk-a-heap” soldiers—infantry armed with long high-powered rifles.

In the Lakota village, the chiefs debated whether to try to make peace with the soldier chief. Sitting Bull still harbored the same thoughts he had on the Little Bighorn bluffs, when he advised his men to let the soldiers go. He had not joined in the attack on the soldier encampment, nor in the subsequent assaults of his warriors. Now he favored a gesture toward the soldiers.

In the camp was a mixed-blood man named John Bruguier. He had ridden into the Lakota camp a month earlier seeking sanctuary from the law. Sitting Bull allowed him to remain. Because he wore flapping leg chaps, the Indians called him “Big Leggings.” Sitting Bull dictated a message, which Bruguier wrote down. It was tacked to a stake and driven into the center of the road the wagon train was following.

I want to know what you are doing on this road. You scare all the buffalo away. I want to hunt on this place. I want you to turn back from here. If you don’t I will fight you again. I want you to leave what you have got here, and turn back from here.

I am your friend, Sitting Bull

I mean all the rations you have got and some powder. Wish you would write as soon as you can.

They were Big Leggings’s awkward words but Sitting Bull’s thoughts, highly presumptuous but not without modest result. Two emissaries advanced on the halted train. The soldier chief would not talk with them, only Sitting Bull. Reluctantly, Sitting Bull joined with several other chiefs and walked to the train. He gestured to his companions to do the talking. They pressed the officer for food and ammunition—and peace. He replied that they had fired a lot of their ammunition today attacking his train; and moreover, he had no authority to make peace. Nor would he feed them, although when the train continued up the Yellowstone, he left behind token supplies of hard bread and bacon.

Gathering the paltry supplies piled next to the road, the Lakotas moved farther to the northwest and on October 20 discovered a herd of buffalo. They encamped on the heights dividing the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers and sallied forth to attack the herd. Almost at once, however, scouts brought word of still more soldiers advancing on their trail. The Lakotas gathered on the ridge and watched the soldiers form in line of battle. To ward off an attack, Sitting Bull hazarded another talk with the soldiers. Two emissaries rode toward them with a white flag. “These troops were on the warpath,” said one of the two. “We ran great risk in going to them, but we went directly to them.”

After an hour of confusion on both sides, a parley was arranged. Groups from each side advanced toward each other. Accompanied by an array of chiefs, Sitting Bull led his party. They bore no arms, although a mounted contingent of armed warriors followed. The day was sunny and clear but bitter cold. A heavy buffalo robe covered Sitting Bull’s plainly attired frame. The soldier chief and his staff rode toward them. They dismounted and hesitantly sat on buffalo robes spread on the ground. Big Leggings stood nearby to interpret. Sitting Bull faced an officer who was to play a large role in his life.

– National Archives and Record Administration –

– Zalmon Gilbert, circa mid-1880s Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

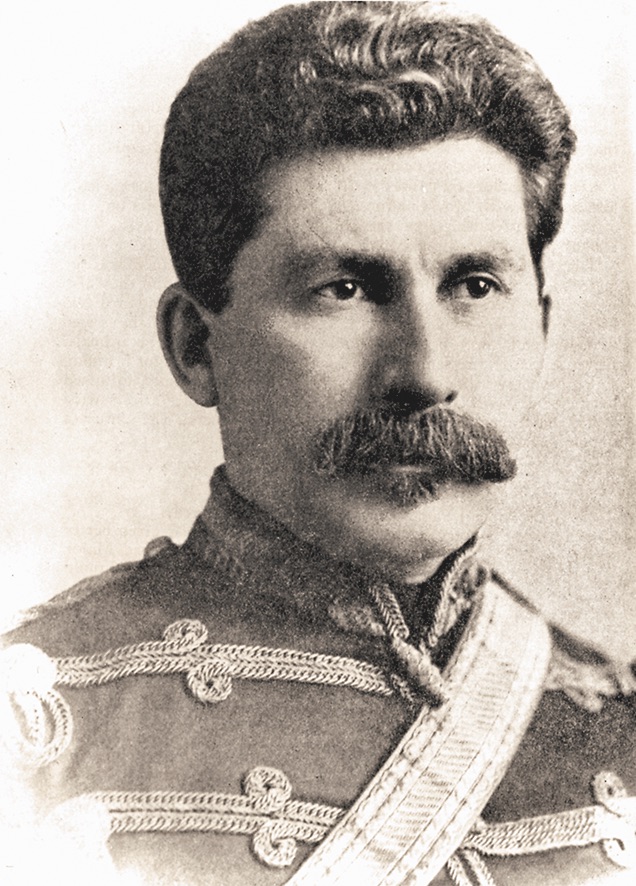

To ward off the cold, he wore a fur cap and a long overcoat trimmed in bear fur. “Bear Coat,” the Indians dubbed him, a name that endured through four years of contention and battle.

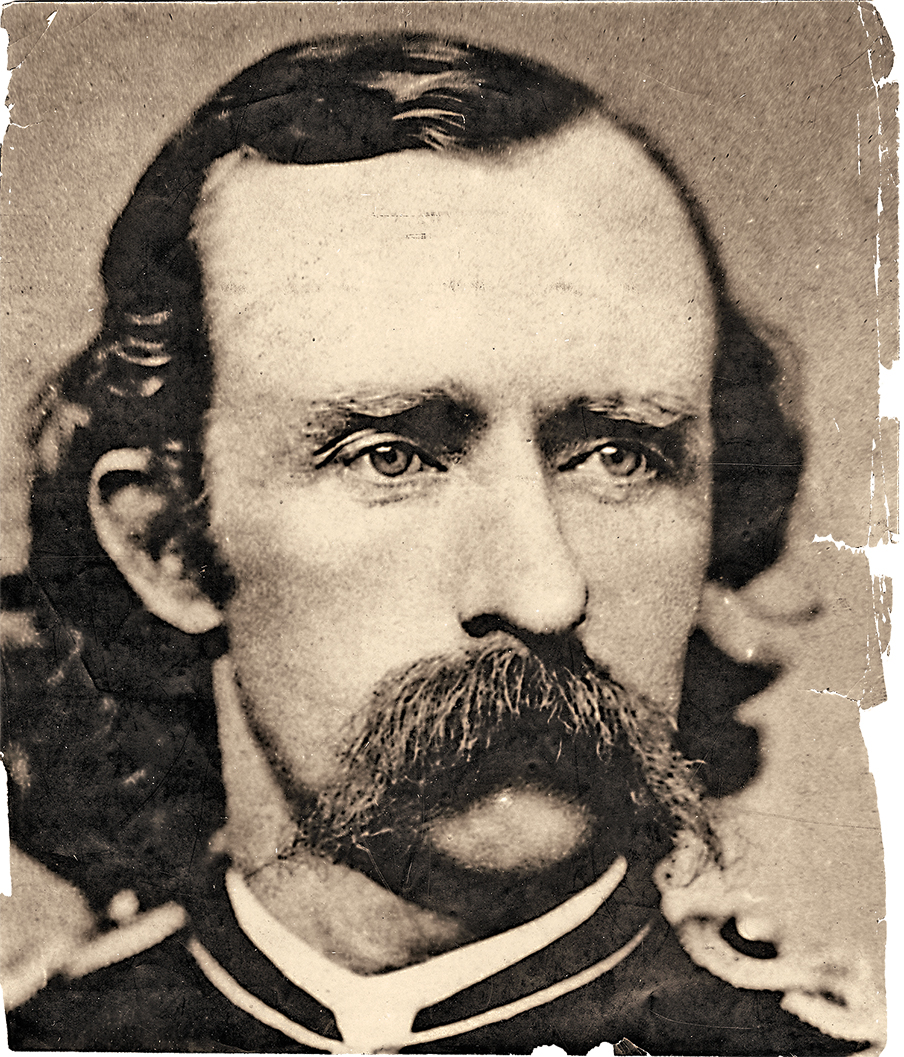

He was Col. Nelson A. Miles, whose 5th Infantry regiment was building winter quarters on the Yellowstone at the mouth of Tongue River. Tall and well-proportioned, with a neat black mustache, he was intensely ambitious, determined to gather all the power and rank he could. His wife’s uncle, Gen. William T. Sherman, headed the Army. Bear Coat intended to stay on the northern plains throughout the winter and carry the war to Sitting Bull—to capture or kill him. Sitting Bull would find this man a dangerous opponent, the more so because he was inclined to stretch his orders to the limit and beyond to swell his reputation.

The talks lasted for two days. Amid the many words, two thoughts prevailed: Bear Coat demanded that Sitting Bull surrender and do as the government wished; Sitting Bull steadfastly refused and told Bear Coat to leave him alone. Frustrated, at the end of the second day both sides formed for battle. The soldiers attacked, and the Indians fought back from higher positions. The fighting continued inconclusively for two days as the Indians made their way 42 miles back to the Yellowstone, abandoning food and camp equipage on the way. En route Sitting Bull and his immediate Hunkpapa following peeled off and turned back north; the Miniconjous and Sans Arcs crossed the river and surrendered to Miles. Sitting Bull’s nephew, White Bull, went with the Miniconjous because he had married into the Miniconjou tribe. One Bull remained with his uncle.

– Bill Nelson Cartography, Courtesy University of Nebraska Press –

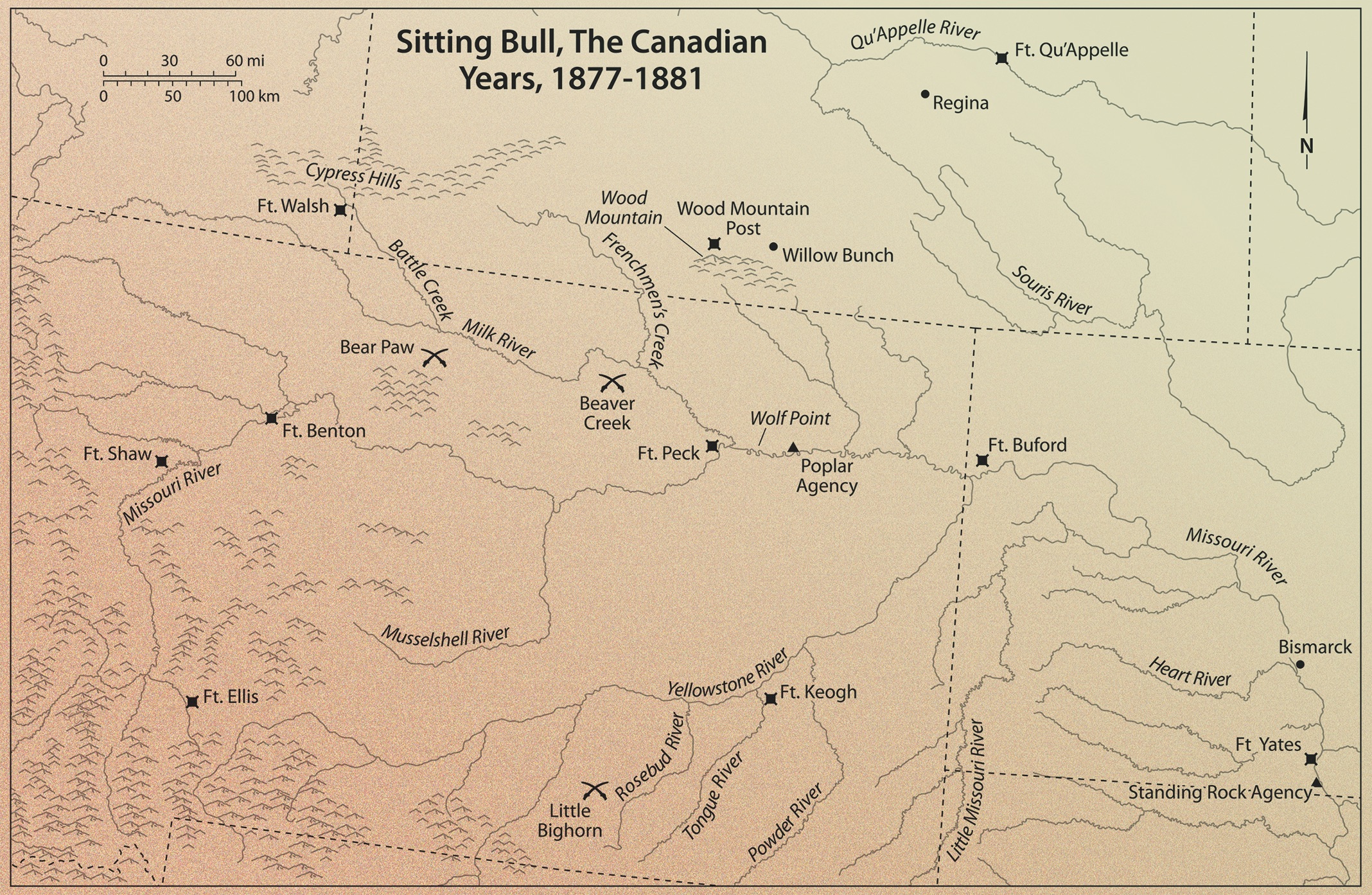

For Sitting Bull, the brutal winter of 1876–77 brought suffering from hunger, poverty, bitter cold with weeks of rain and snow, and repeated hasty moves to avoid Bear Coat’s relentless campaign. The soldiers kept to the field all winter, ranging up and down the Missouri River where it flows east before turning south. On December 18, a unit of Miles’s soldiers overtook Sitting Bull’s village of about 120 lodges and attacked. The Indians abandoned their dwellings and fled south, the soldiers in pursuit. Left behind, besides ponies, food and all other possessions, were piles of buffalo robes, which the soldiers took back to their winter quarters to have made into overcoats.

– Courtesy Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta, Canada –

Increasingly destitute, increasingly frightened by Bear Coat, Sitting Bull agonized in uncertainty. Increasingly, he pondered taking refuge in Canada, the land of the White Mother. This option grew more appealing as Four Horns, Black Moon and other Hunkpapa chiefs crossed the line late in 1876. In the Lakota mind, the boundary took on almost spiritual meaning. “They told us that this line was considered holy,” recounted one of the Lakotas. “They called that a holy trail. They believe things are different when you cross from one side to another. You are altogether different. On one side, you are perfectly free to do as you please. On the other, you are in danger.” Sitting Bull did not view Canada in such simplistic terms. He did not want to leave his own country, and he avoided a decision, even as his shrinking following moved closer to the holy line during the early months of 1877. On March 17, they crossed the Missouri River and pitched their shelters on the north bank. That night the winter’s ice pack in the Missouri River broke up and sent a giant wall of water down the river. It swept over the Lakota camp and damaged or destroyed nearly all their possessions.

– Courtesy Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada –

– Courtesy of the National Park Service, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, LIBI_00019_00308, Unknown Photographer, “Enlargement of a Headshot of General George Armstrong Custer,” circa 1865 –

Everyone recognized that the time for decision was overdue. On April 10, 60 miles north of the Missouri, they convened a council of a dozen chiefs. Sitting Bull spoke in favor of continuing the war until the white soldiers surrendered. Not for the last time, his wishful thinking had converted fantasy into reality. Contradicting himself, he declared that he would cross the boundary and wait until he could discover how the people who had preceded him were treated. Sitting Bull had been in Canada before, principally to trade with the Red River mixed-bloods the Lakotas called Slotas. Now Canada posed uncertainties: were there enough buffalo to feed the Lakotas? Would the tribes native to Canada welcome or fight them? Would Canadian authorities treat them fairly? These and other unknowns plagued Sitting Bull and his followers, but all paled before the reality of poverty and constant fear of Bear Coat’s soldiers suddenly dashing into their village—a village grown much smaller because so many of the Lakotas, including Four Horns and Black Moon, had already sought refuge in Canada.

Despite the conclusions reached in the chiefs’ council of April 10, Sitting Bull and his people continued to move slowly northward. The village now counted 135 lodges, about a thousand people, and all suffered terribly from the Missouri River flood that tore through their dwellings. They edged up Milk River from its confluence with the Missouri, then turned north on Frenchmen’s Creek. Early in May 1877 they crossed the chanku wakan, the sacred road.

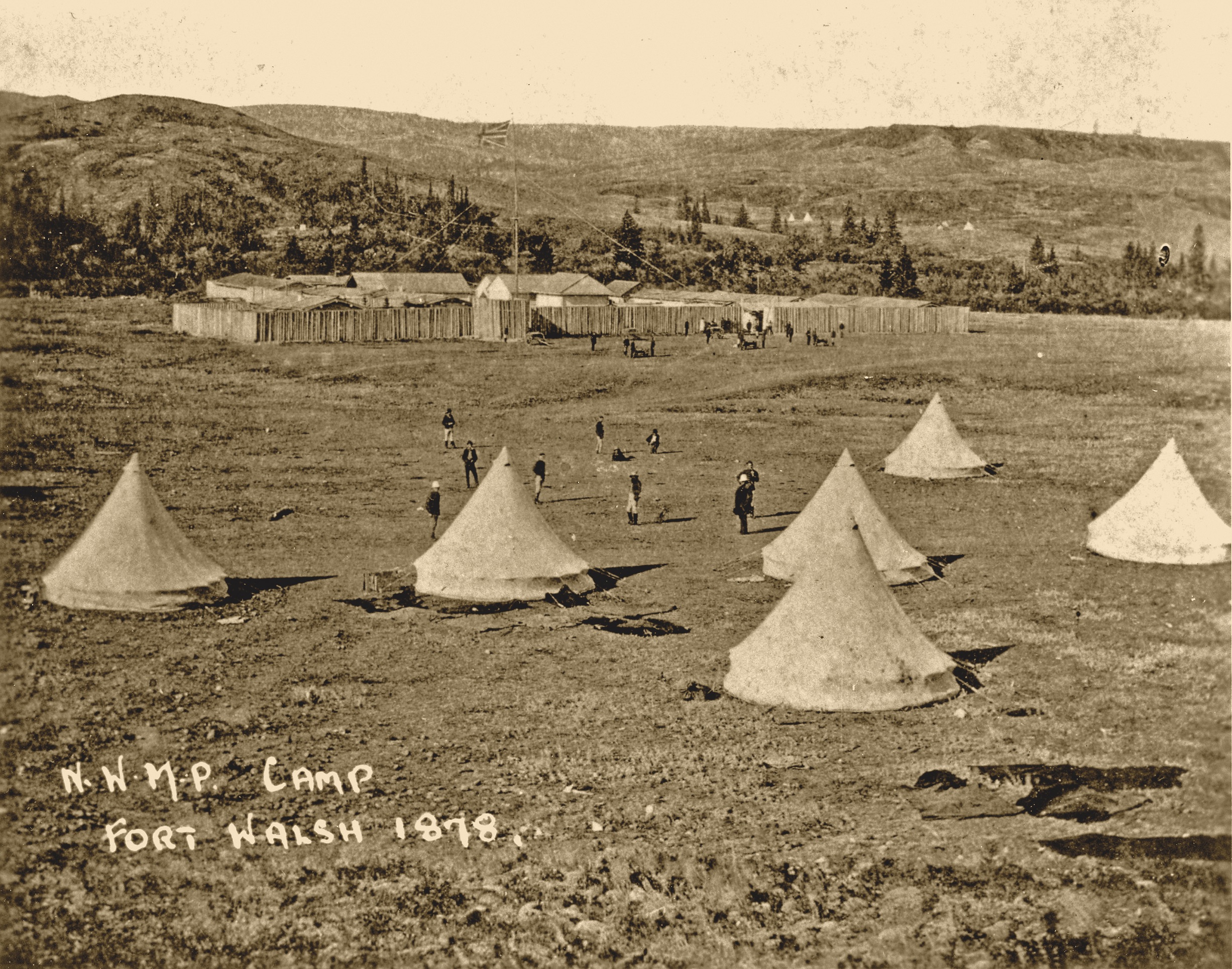

Now in Canada, they continued up Frenchmen’s Creek, which the Canadian maps labeled the White Mud Creek. About 60 miles farther, they reached a headland called Pinto Horse Butte. Watered by the White Mud, which rose in the timbered Cypress Hills to the west, Pinto Horse Butte rested on the northwestern end of Wood Mountain. It afforded a good place to camp without worrying about Bear Coat. The people had rested a few days when lookouts sighted seven mounted men approaching the village. Some wore scarlet coats and white helmets. They boldly advanced, seemingly unafraid of the Indians, dismounted and walked toward the tipis. The Lakota lookouts had been circling the party long enough to bring word to the village of the intruders. Who they were, remained to be learned.

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

Robert M. Utley is a preeminent historian of the West and the author of numerous award-winning books. “Sitting Bull: The Sioux Leader’s Final Flight to Freedom” is an excerpt from his latest book, The Last Sovereigns: Sitting Bull & The Resistance of the Free Lakotas (University of Nebraska Press, 2020).