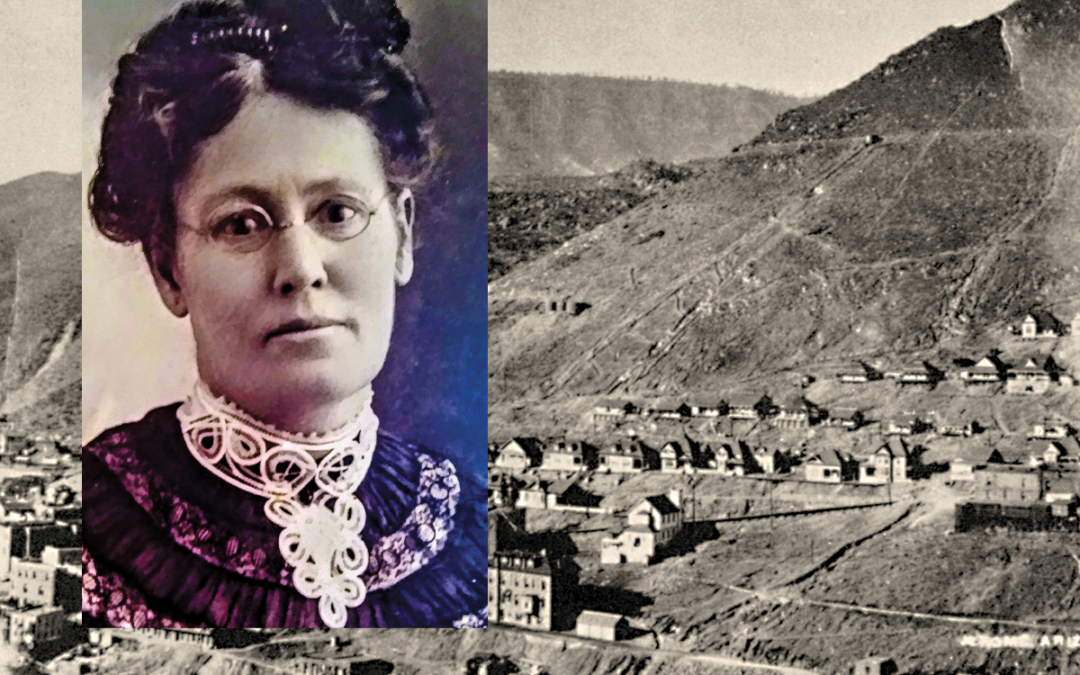

History tried to erase the courageous Arizona journalist, but her remarkable life and work as a publisher is a testament to her courage and her undefeatable spirit.

This isn’t a story about a woman history ignored or forgot nor diminished. That wouldn’t be news.

This is a story about a woman history tried to erase. Her enemies wanted to be sure she was buried—without a gravestone. And they almost got away with it.

I stumbled on Laura Nihell while visiting friends in Jerome, Arizona, on March 28, 2014. I picked up a book in their library written in 1964 by Herbert Young titled Ghosts of Cleopatra Hill: The Men Who Built Jerome.

Luckily, this wasn’t an original copy, but one issued 37 years later, in 2001, when Alene Alder added her chapter on “Women of Cleopatra Hill.” It was, of course, at the back of the book.

That’s where I found Laura Nihell, described in 131 words.

Bells and whistles started going off. As a journalist, why didn’t I already know about this woman, who had owned and edited a newspaper in Jerome in the early 1900s? Why wasn’t she in the centennial book just published on the history of female journalists in Arizona? Even I’m in that book.

When I got back to Phoenix, my first stop was the Arizona Archives, one of the state’s true treasures. They have everything you want to know about territorial days in that wonderful library—but not one word about Laura Nihell. They’ve never heard of her.

She wasn’t in the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame. Or in the Arizona Room at the Phoenix Public Library. Or mentioned in any of the state’s three university libraries.

Nothing.

I even found a publication of the Jerome Historical Society titled “Herstory of Jerome.” There’s not a hint about Laura Nihell.

So, 131 words was all she gets? I already knew that wasn’t fair.

Because those 131 words had grabbed ahold of me and yelled, “Hi there, honey. Meet a bona fide Western heroine.”

They told me Laura Nihell, a 52-year-old former teacher and married-into-a-good-family-mother-of-two-sons, had done something brave.

They told me that Laura Nihell, a woman who couldn’t vote or sit on a jury in Arizona Territory, whose “sphere” was supposed to be her home and children, had fearlessly stepped out of that role into a man’s world and went to battle.

They told me that Laura Nihell was a woman unafraid to fight for truth and honesty. That she valiantly stood against bigotry and bullishness.

A Life-Changing Move

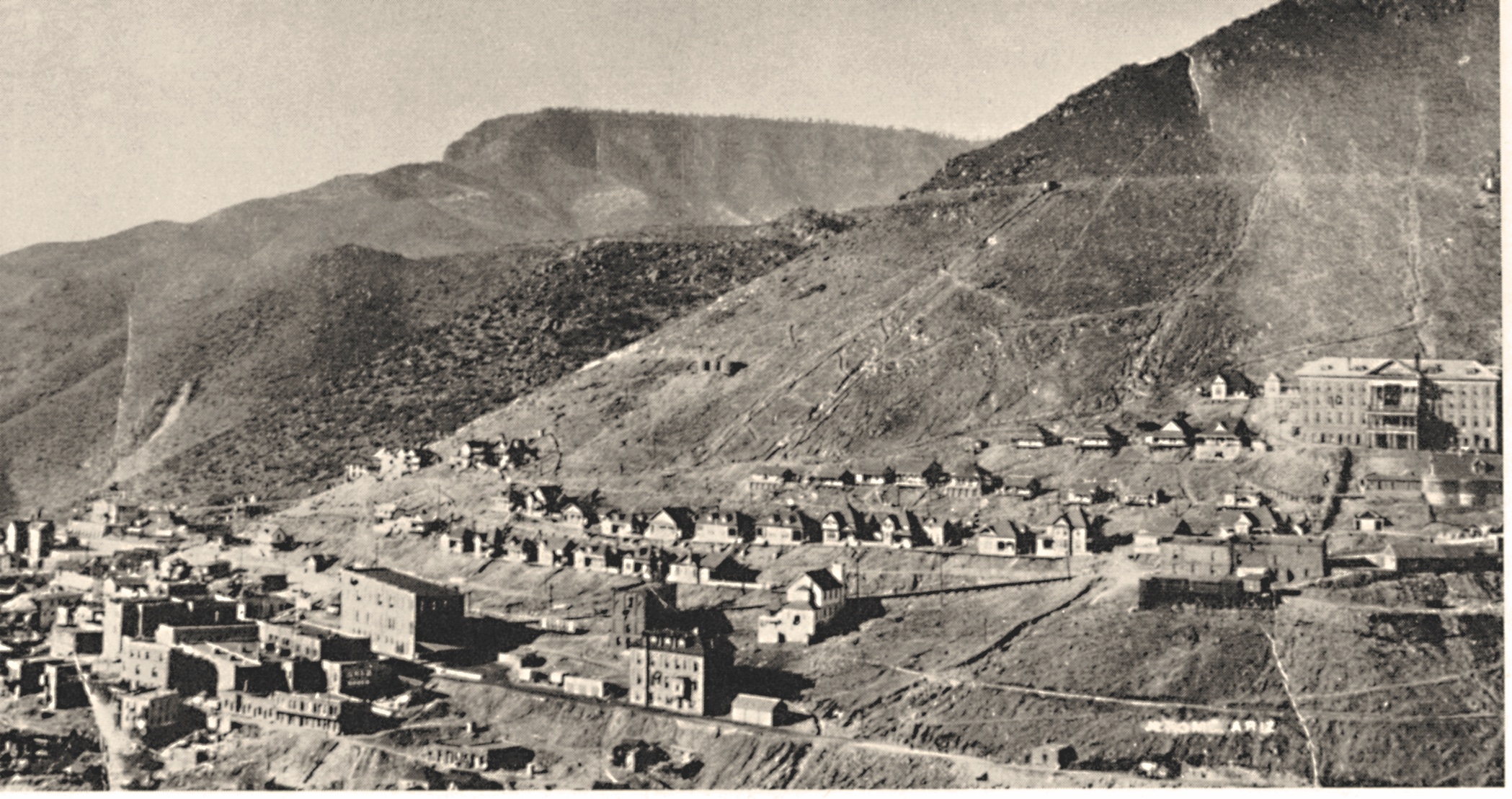

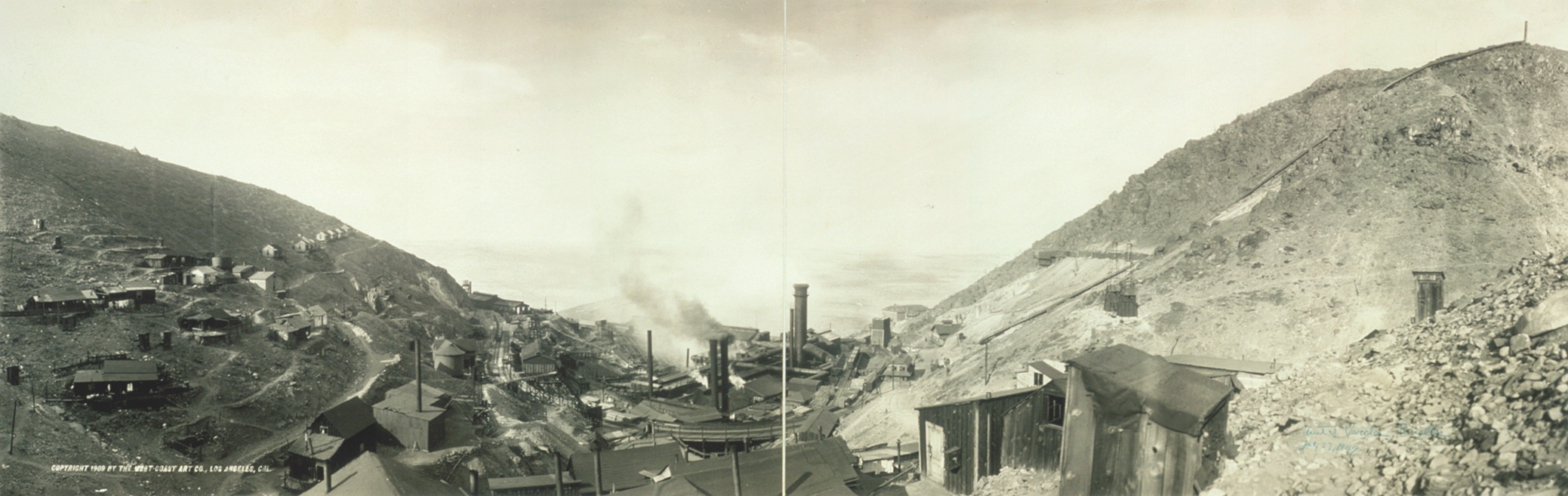

The census tells us that Laura’s family moved to Jerome by 1900—37 years after Arizona was finally named a territory; 24 years after the first mine claims were filed on Cleopatra Hill in a mining camp that would become Jerome; 15 years after Territorial Governor Frederick Tritle took Jerome copper samples to the New Orleans World Exposition and caught the eye of a Montana tycoon named William Clark; and 12 years since Clark became the king of this hill with his United Verde Mine that would become the richest copper mine in the world. (By the way, Clark bought the mine on February 14, 1888—exactly 24 years to the day before Arizona became the 48th state.)

By the time the Nihells arrived, Jerome had incorporated as the fifth-largest city in Arizona Territory and had a population of 2,861 residents—78 percent of them men. It would grow to be the territory’s third-largest city with a population over 15,000 but that was a ways off. Even farther off was the day it became a ghost town, or as one historian put it, “the town emptied like a fish stand after a case of salmonella.” But that was decades after this heyday chapter of Jerome’s life.

Jerome already had an opera house, a half dozen hotels, a public library. It had telephones but not electricity. It had three newspapers and four churches.

The Nihell family lived in the better part of town. Laura’s husband, Isaac, was a tinsman and a plumber. The boys were in elementary school. Laura was the Jerome correspondent for the Prescott Journal Miner, which billed itself as “The Pioneer Paper of Arizona.”

Laura was welcomed and praised when she bought the Jerome Copper Belt weekly newspaper in 1909. The praise came from her competition, the long-standing editor of the Jerome News, William Adams.

Mr. Adams told his readers that Laura was “one of the best news rustlers in the country.” He liked her so much, he even enlisted her to take over his paper when he was out of town.

Her purchase put her in a very rare sorority—she became the third woman in the territory—at that very moment—to own a newspaper.

The first was Josephine Brawley Hughes, who owned the Tucson Star with her husband, Louis. They became quite a force in Arizona. He became a territorial governor; she headed both the temperance and suffrage societies.

The second was Angela Hutchinson Hammer, who, on her own, had newspapers in Wickenburg and Phoenix. And she founded the Casa Grande Dispatch.

And now here came Laura as the third. Did any other territory have that bragging right?

Jerome was then known as one of the territory’s most melting-pot communities and quite a notorious place. An Eastern paper called it the “wickedest town in America.” Somebody said with a wink, “Jerome is not a city of churches, but hopes to be worse by and by.” But Jerome didn’t see itself like that. It once tried to contrast itself to sinful Tombstone by bragging that Jerome was a “sinless, model community inhabited

by honest men and pure women.” Nobody believed them.

I’m betting Laura was a supporter of the important issues for women in 1909 as she took over the Copper Belt.

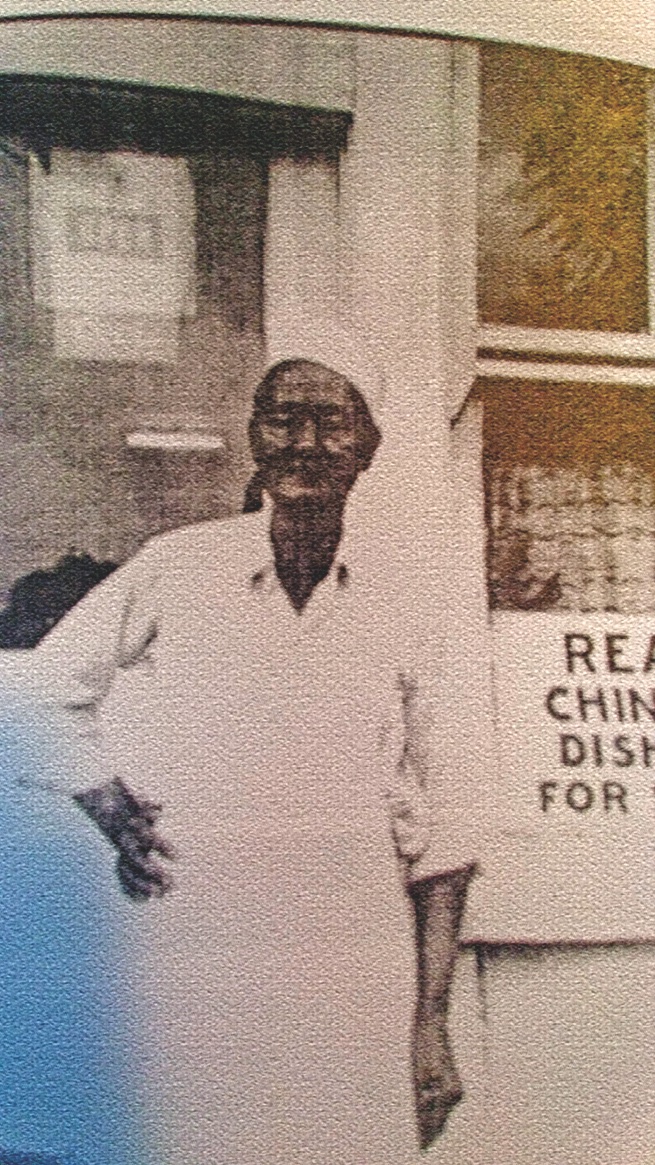

Like everyone else in town, Laura and her family regularly ate at the most popular restaurant in town, Charlie Hong’s English Kitchen. Of course, she knew him; everyone did. He was one of the most popular guys in Jerome—also one of the richest, and he paid more property taxes than most of the White business owners. He was a real celebrity.

William Adams of the Jerome News had praised Hong more than once in print—that, in itself, a pretty remarkable thing, considering that territorial newspapers were almost universally railing against Chinese people being in the territory at all.

Mr. Hong escaped that wrath for a decade—and he may have been the only Chinese man in the territory who got any good press.

Adams lavished on the praise when Mr. Hong was the first business to rebuild and reopen after the fire of 1899 that destroyed most of the Jerome business district. Mr. Adams breathlessly wrote: “There is no more popular man in Jerome than little Charley Hong, and he numbers his friends among all walks of life.… His credit is good for any amount with merchants, and he enjoys the enviable reputation of feeding more people than any other restaurant in town. He is American in all but birth. What more could be said.”

Okay, patronizing praise, but still praise.

In the summer of 1909, Mr. Hong went home to China to visit his family. He returned, making the mistake of coming through Nogales, which wasn’t a registered port. The government threatened to deport him. But he was defended by the Jerome News. Editor Adams reminded his readers in July that “Hong is classed with the best Chinese in Jerome.”

But he also added, “If we must have them with us, there can be no objection to Hong as one of them.”

In two months, all that changed.

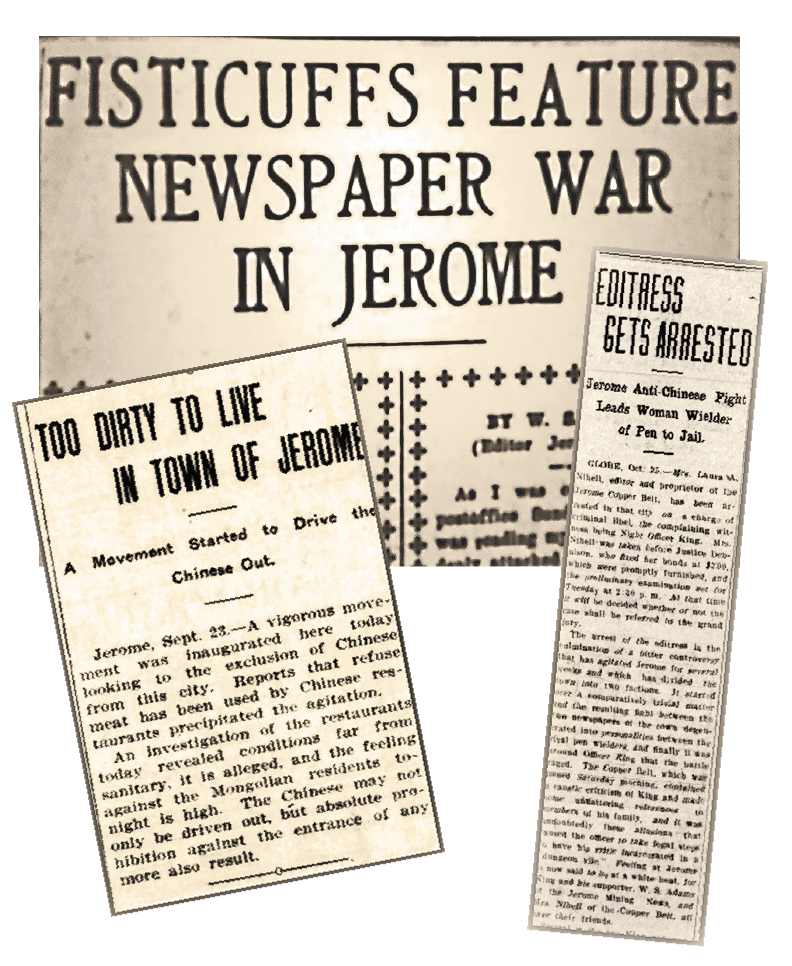

In mid-September, Jerome was scandalized when the Jerome News unleashed an expose: Constable Charles King was charging that Chinese restaurants were raiding garbage boxes and serving “filthy meat” in their restaurants. King said he followed one Chinese crew right to Charlie Hong’s restaurant!

The charge came from a suspicious source: Charley King’s wife was trying to open her own restaurant, and Adams was using his newspaper to promote it as a “white restaurant” with “a clean white kitchen.”

We’re indebted to historian Kathryn Reisdorfer of Yavapai College in Prescott, whose excellent examination of what happened next appeared in the Journal of Arizona History in 2003. She pulled no punches: “Charlie Hong, Racism, and the Power of the Press in Jerome, Arizona Territory, 1909.”

(This is the only historical article I found that mentions Laura Nihell—she’s not a major character in the story—and that it didn’t inspire other historians to take a closer look at her still puzzles me.)

Mr. Hong immediately protested, saying the charge was a lie. Hong said that he used refuse meat to feed his pigs at his farm in the valley, but certainly not in his restaurant. When Adams wouldn’t listen to his pleas, Mr. Hong went looking for help from the other newspaper in town, Laura’s Copper Belt.

She was printing her paper every Thursday from her offices in the basement of the New York Store on Main Street. She charged five cents a copy, $2 for a yearly subscription.

If I could be a fly on the wall of history, I’d want to be in that basement when Charley Hong came in to tell Laura Nihell his story. Did she grill him? Did she worry this would be an unpopular mess to get mucked up in? Did she hesitate?

It surely struck her that a White woman—already infringing on a man’s world just by owning her own paper—would really be pushing the boundaries if she stood up for a Chinese community that was being slandered by the most powerful male-owned newspaper in town. There could be disastrous consequences—she certainly knew that.

But from what happened next, I’m betting she didn’t need a lot of convincing, she didn’t hesitate, and she didn’t flinch. She had the backbone to stand up against the drumbeat of racism, knowing she’d probably be standing alone.

Laura printed Mr. Hong’s letter with his strenuous denial and his countercharges on why he was being attacked: No. 1, Constable King was trying to kill the competition for his wife’s restaurant, and Adams was helping him. Plus, Hong wondered, how could his food be so filthy when the constable regularly stopped in to help himself from the kitchen—never paying?

And speaking of being a freeloader, so was Mr. Adams from the Jerome News. No. 2, Hong charged that Editor Adams was on the bandwagon against him because he had demanded Adams pay his outstanding bill.

Laura not only let Charlie Hong speak directly to the people of Jerome, but she also added her own voice. Her exact words haven’t been preserved, but we can figure out what she said by the reactions she got.

She supported Mr. Hong without equivocation.

She dismissed the charges as ridiculous and vile.

She reminded Jerome that Editor Adams had lavished praise on Mr. Hong just months earlier.

And she mocked his accusers in a way that cut to the quick. She always referred to Constable King as the “gallant officer,” clearly meaning he was anything but. And here’s how we know she had a wicked sense of humor—she called Editor Adams—“Confucius 11.”

At some point she must have written something like, “It’s a privilege to stand with an honest, decent human being who’s being slandered by freeloading bigots.” Or words in that neighborhood.

We know all that because this was the reaction printed in the Jerome News: “God, the pity of it, that White people should stoop so low as to crave the privilege of protecting them.”

In his September 18 edition, Editor Adams had his own say and printed his own open letter to Jerome—this one from Constable King.

King declared: “If the men, women and children who patronize them knew but half of the filth that is passed out to them, they would never eat a meal in a Chinese restaurant.”

Editor Adams wrote that King could have gone farther: “…he might have added that those whom they feed are blind to everything or they would not partake of food that must be unfit for any human being to eat, and in doing so, keep the life blood in leeches and in this way, assist in keeping a white restaurant from doing business in our city.”

But Adams wasn’t content to rest his argument on the charge of filthy food. He didn’t want to just destroy Charlie Hong’s business, he wanted to destroy Charlie Hong. Now he called for him to be deported.

He wrote. “Hong is what they call in New York City a ‘Christianized Chinaman.’ The Christianizing of Hong has been his downfall.” He claimed Mr. Hong was “butting in on all church social affairs” and dared participate in a basket social, where the single girls of the parish offered a picnic basket, sharing the meal with the highest bidder. Adams said Hong “humiliated a white woman,” by outbidding everyone for her basket. (Adams particularly favored the “lusting-after-white-women” attack.)

On October 2, Adams printed his most hysterical piece: “Found Maggots in Soup in Hong Restaurant….”

Every week there was a new horror story. Some are so absurd you want to laugh out loud. Like the one where he claims a couple found cockroaches in their salad…and bedbugs in their pie—WHAT? They ate the whole meal? Did they pick around the bugs?

Adams now was attacking all Chinese residents in Jerome, not just Hong. And he didn’t hesitate to use racial slurs. He wrote, “We believe in the doctrine of America and Americans and will always be found preaching it against a dirty, greasy chink.”

Then he demonized the entire race and any Americans who didn’t see it his way. He wrote: “In their crazy frenzy, the chink protectors forget that they are Americans and are attempting to uphold at the expense of American labor, institution and citizenship, the lowest tribe on earth.”

Laura was giving tit for tat, rebutting the hysteria of the Jerome News and reminding Jerome about the Charley Hong they all knew and respected. It was too much for Adams to take.

On October 16, he published a front-page cartoon to humiliate Laura. He called her their “missionary” and declared, “A chink protector is a worse menace to American manhood and womanhood than a chink.” He called her “Old Mother Petticoats” and an “old hen.” He complained, “Laura Nihell for the last few weeks has indulged in expletives not taught her sex where good breeding is inculcated.… It is not to our liking that we notice the mudslinging of a woman; it would be far preferable to wield a pen in defense of the gentler sex; nothing could please us better than were the female sex never in need of vindication.”

And worse yet, Adams insinuated, several times, that there was a sexual component to Laura’s defense of Mr. Hong.

While Arizona records show us years of editions of the Jerome News, and all these articles—preserving forever their racist headlines—suspiciously, not a single issue of the Copper Belt published by Laura has survived. There are copies of the paper before her editorship, and after her editorship, but not during. So, you could read territorial newspapers all day, and believe that everyone, universally, hated the Chinese. And never realize that in one town at one time—and this may be the only example we have—the Chinese had a champion, thanks to a female journalist.

No, we didn’t have any of Laura’s papers that survived.

Until I went digging into a libel suit Constable King filed against Laura Nihell. This was news throughout the territory, reported in several papers. He claimed she published “a malicious defamation…which tends to bring himself and his family into disrepute and ridicule.” It was filed on October 23, 1909.

I figured it had to be filed at the Yavapai County Courthouse in Prescott. I never dreamed it would hold such a treasure.

I got copies of the whole file: Laura had been arrested, but the judge released her on a $300 bond until a trial date, set for the next week All that paperwork was there, along with the complaint King had filed—and Exhibit H.

To prove his point, King submitted the entire edition of the Copper Belt that included the “libelous” article. The court called it Exhibit H.

It is the only copy of Laura’s paper that has survived.

We no longer must guess what Laura said or glean her words from the reactions. We can hear from her own pen how she faced off against Adams.

She wrote: “The Copper Belt regrets that in justice to itself, it is compelled to again refer to that dirty and villainous plot of the Jerome News.… The climax in the fight of W.S. Adams, alias Confucius 11, and his gallant officer friend was reached this week when they tired in their unsuccessful efforts to draw the Copper Belt into their dirty, unjust fight against the Chinese restaurant keepers of Jerome.

“Why did this gallant officer go to Charlie Hong’s and demand to know why he wrote his article, and threaten to run him and all the other Chinamen out of town within 24 hours?”

Laura wondered how Charlie King could so attack the Chinese restaurants when his own family, including Mrs. King, “had been averaging one meal a day there up to this time and passed directly by a white restaurant to get there.” [That was the libelous part! That the King family ate in Hong’s restaurant!]

And, she asked, “Why should this gallant officer visit these Chinese kitchens at night, when he was on duty, helping himself to their pots and pans and standing while he ate, when things were so dirty?”

Her last big blast made it clear she felt he was a poor excuse for a constable: “If Officer Charles King will attend to the business for which he is paid, and devote less time to dog fights, he may save himself from a fate that awaits him as chamber maid at a livery stable.”

And Laura pleaded for her town: “Why should the fair name of Jerome be besmeared with such scurrilous articles as have been appearing in the Jerome News?”

Editor Adams now demanded the Jerome City Council do something, and it did. It sent an inspector to Charley Hong’s English Kitchen. It found absolutely nothing wrong.

I couldn’t find a headline in the Jerome News acknowledging that Mr. Hong had been exonerated by the City of Jerome. But I bet there was one in Laura’s paper. Maybe a stacked headline in the style that was so popular in that day, reading something like: “Charley Hong Cleared. No evidence of wrong-doing, city says. Jerome News discredited for racist attack. Mr. Hong thanks residents for standing with him during these trying days.” Or something like that.

Territorial newspapers started paying attention when it turned into a street fight.

Thankfully, we have both sides of this story, courtesy of the Prescott Weekly Journal, which solicited columns from both editors for their story on “The Newspaper War in Jerome.”

Here’s how Laura told the story: “The Jerome News, edited by W.S. Adams, in its last issue contained remarks toward me that were slurring, unprincipled, undignified and not becoming anyone in the newspaper profession. My son, who is a slender boy, weighing but 125 pounds, while Adams weighs about 195, resented the attack on me and engaged Adams physically on the street. How much he would have punished Adams had not an outsider interfered I do not know, but I stand by him in everything he has done.”

She went on to declare:

“I am not to be bluffed nor bullied and I propose to continue to write things as I see them, free and unhampered by any influences. Those are my sentiments and I believe that they meet with the approval of the vast majority of Jerome people.”

When Adams told his side, he said he was attacked from behind as he returned from the post office on a Sunday morning. He described Mrs. Nihell’s son as “an athletic youth but 21 years old while I am 53 years of age.” He said his glasses were ripped off, leaving a cut on his face, and for the life of him, he couldn’t figure out the motive because, and let me quote, “In all of my writings, I have endeavored to keep from becoming personal and have referred to the Jerome Copper Belt simply as a newspaper. I consider the attack unwarranted and unjustified.”

By Thanksgiving, everything died down. And it was clear that Laura Nihell and Charley Hong were the victors.

The court dismissed the libel suit against Laura, and she got back her $300 bond. She continued editing her newspaper for three more years, until 1912, after Arizona finally became the 48th state. The family moved back to San Diego.

Mr. Hong wasn’t deported. He wasn’t forced out of his restaurant. He didn’t leave town.

He became a naturalized citizen and registered to vote.

His English Kitchen kept its status as the most popular restaurant in Jerome, until he moved on in 1913 at the request of none other than William Clark himself, who built a restaurant for Charlie Hong in the community he created for his mine workers, called Clarkdale. Mr. Hong eventually went back to China for his final years.

In contrast, Constable King had a horrible ending. He was shot and killed.

Mr. Adams died in 1932 at age 74 and got a very nice obituary in the Verde Copper News: “Prominent Pioneer of Southwest Dies in Hospital Here.”

Laura Nihell died of bladder cancer on May 8, 1916. Her obituary in the San Diego Union called her a “philanthropist who once ran a newspaper in Arizona.” She was 59. She had been president of San Diego’s Pioneer Society.

In the summer of 2019, I visited her grave in Mount Hope Cemetery in San Diego. It was a very emotional moment—having searched for over five years, I could finally pray at her grave and tell her how proud I am of her.

I want Arizona to acknowledge Laura Nihell as a point of pride. I want American journalism to celebrate her courage.

Why did history try to erase her? Because she dared buck the tide. She had the courage to stand up for an unpopular cause.

I think her courage embarrassed the bigoted leaders she challenged, and her ridicule mortified them. And then she won—she bested those bigots! And the only way her enemies in Jerome could get even was to be sure history ignored her.

They almost got away with it.