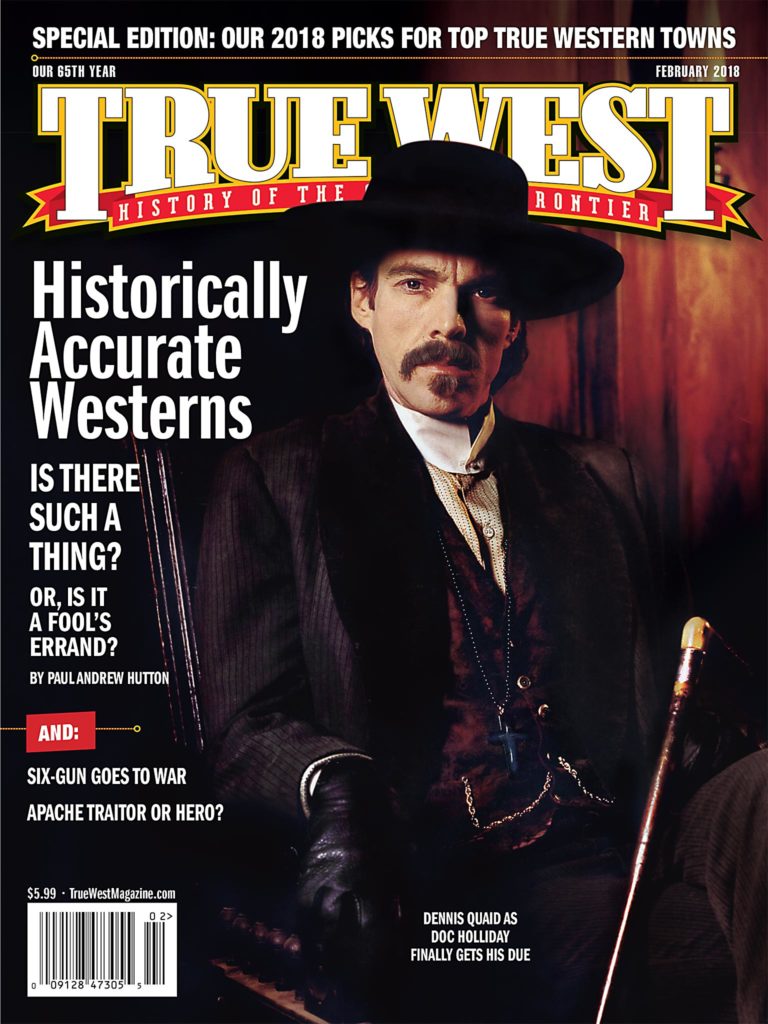

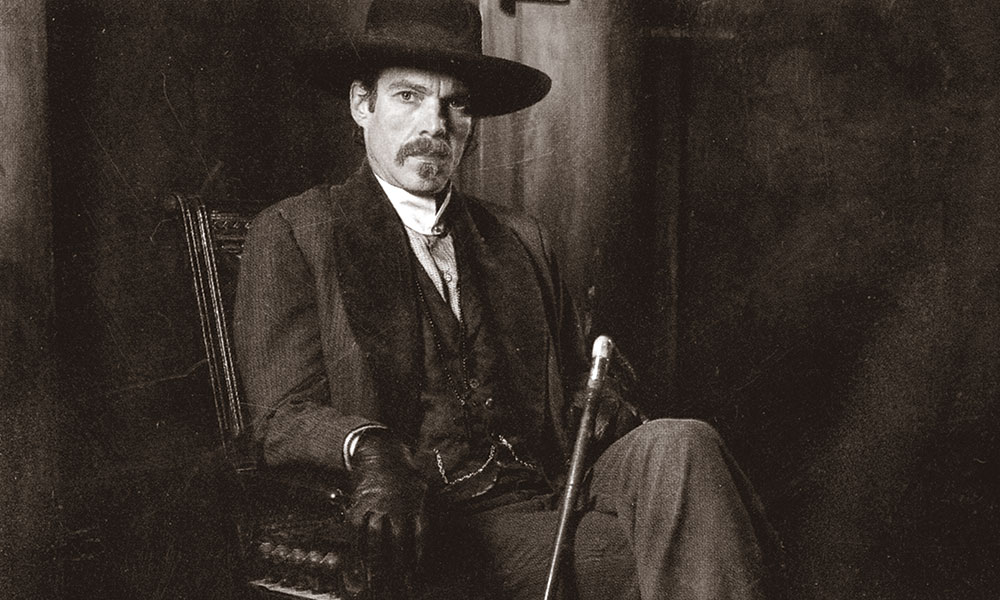

— Wyatt Earp photo By Ben Glass —

To put it mildly, we at True West have been overjoyed—nay, overwhelmed—by our readers’ responses to the deceptively simple question: Which is the most historically accurate Western film, and why? With nearly 1,000 responses, we mulled over plenty of nominations.

If we wanted to go by sheer numbers, according to our readers’ responses, we could say 1993’s Tombstone wins with 125 votes, 1989’s Lonesome Dove places with 124 and 1992’s Unforgiven shows with 36, and be done with it. But this should not be merely a popularity contest. That’s why we also asked some of our historical experts, film scholars and passionate fans to weigh in.

Even our readers’ top vote-winners raise questions as to the meaning of historically accurate: Tombstone tells a story about real people and true events. Lonesome Dove is a work of fiction inspired by the true story of Oliver Loving and Charlie Goodnight. Unforgiven is a work of pure fiction, yet is so powerful, that the movie is one of only three Westerns to win the Best Picture Oscar, along with 1990’s Dances With Wolves, with 25 votes, and 1930’s Cimarron, with no votes.

— Wyatt Earp photo By Ben Glass —

No disrespect to Wesley Ruggles’s Cimarron, a wonderful film, for which RKO built the largest Western town in American film history, but who of late has had a chance to see it? The same goes for Raoul Walsh’s wonderful The Big Trail, released the same year, or any of a dozen great silent Westerns. The fact that they are difficult to track down makes them no less accurate.

Does Tombstone’s adherence to provable facts make it the most accurate? Or is a correct capturing of time and place and people as meaningful a definition of accurate? Truth, and even being there, isn’t everything. Lawmen like Bill Tilghman and outlaws like Al Jennings made their own movies, but Tilghman’s are so primitive, they’re barely watchable, and Jennings’s, while entertaining, are more self-serving than informative.

Logically, 1946’s My Darling Clementine should be the most accurate telling of the Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral, since Wyatt Earp shared his memories with friend and director John Ford. For entertainment value, it may be the best film on the subject, but it ain’t history.

So, in choosing the Absolute Best Historically Accurate Westerns, we’ve made our selections in several different areas. We’ve looked at accuracy of biography and of specific historical events. We’ve looked at proper period costuming, proper weaponry, proper sets and locations, proper casting and proper representation of day-to-day life of real Westerners, from cowboys to lawmen to outlaws to soiled doves.

We also take entertainment value into consideration—it doesn’t matter how accurate a story is if you can’t keep awake through it. Nicholas Ray, whose Westerns include 1957’s The True Story Of Jesse James and 1954’s Johnny Guitar, called “cut” on a scene one day, and the script supervisor told Ray he had to do another take, because one of the characters had their cigarette in the wrong hand. Ray shook his head, and with a grin, he said, “Listen honey, the vaults are full of movies with perfect continuity that are unreleasable.”

—Henry C. Parke, True West’s film editor

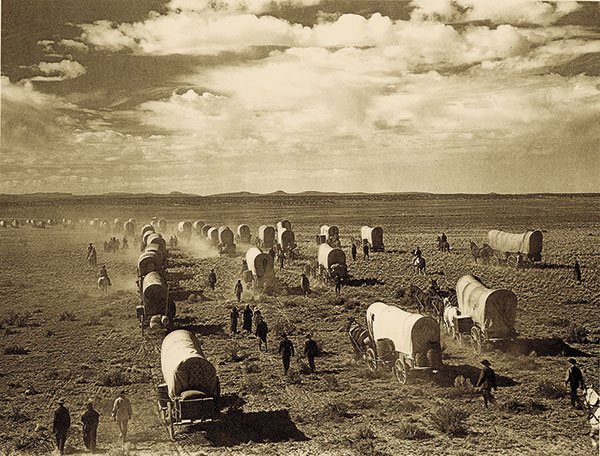

The Covered Wagon (1923)

The Covered Wagon was the template for every Western ever filmed since its release…. Not only is every scene classic, it was the first time many of the historical events were ever put to film. And they were shot without gimmicks nor special effects, yet just like the original pioneers actually accomplished them. In addition, the acting is surreally “non-silent film style”—natural and completely unlike the weird machinations of grandiose face and body movements so typical of acting during the silent era. A lot of credit has been given to John Ford’s silent Westerns, especially The Iron Horse, but it doesn’t hold a candle to The Covered Wagon. —Danny “Ramblin’ Jack” O’Connell

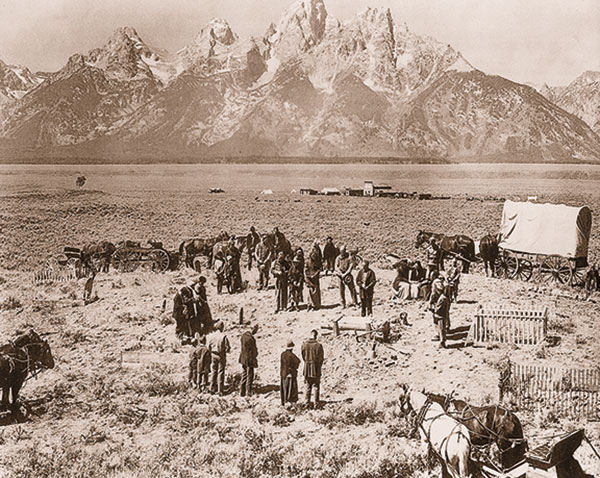

Brigham Young (1940)

One of the advantages to the older Westerns is that the clothing, props and wagons were still around mere decades after the passing of the Old West and in many cases, still being used! We have seen the above still and this one passed off as historical photos—that’s how good the authenticity is in these scenes. —Bob Boze Bell

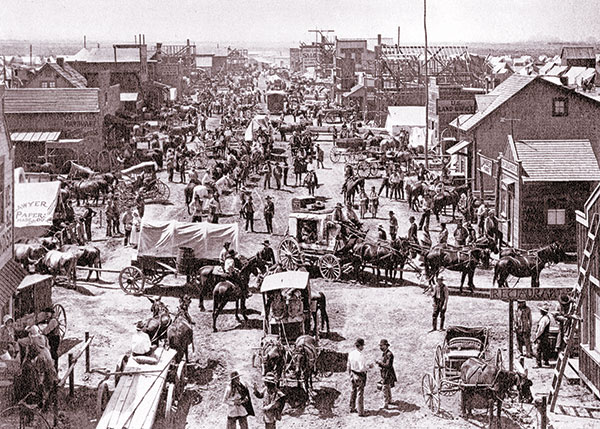

Cimarron (1931)

This early film pulled out all the stops to create a sprawling Old West town in what turned out to be the largest Western town set in American film history.

—Bob Boze Bell

Shane (1951)

Some of the early Westerns don’t get credit for trying to be authentic, but here is another film that tried to get it right. Great look, a very authentic looking scene.

—Bob Boze Bell

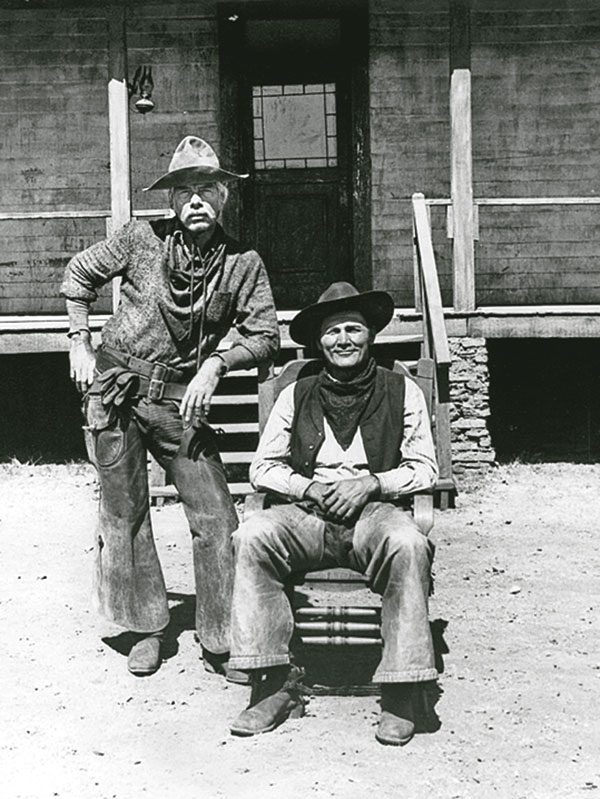

Monte Walsh (1970)

Shane was about who owns what and what they will do to retain their “supposed” land. A much better story was Monte Walsh, with Lee Marvin. Although Marvin and Jack Palance were a bit long in the tooth to play cowboys, they were no worse then the 200-plus-pound cavalry troopers.

But Monte Walsh deals with so much more. The end of an era. A “what do we do now?” situation. The barely accepted new hand Shorty trying hard to fit in (and may well have, at a later date). [Another cowhand,] Chet Rollins, sees the writing on the wall and tries to change with the times, but to no avail, as the survival of one becomes the end of the other. Even Monte Walsh tries to change, and just might have, had it not been for the death of the countess.

Walsh is the one having the hardest time of it. He wants to move on, but doesn’t know how. He has a code, and he can’t break it. He won’t be a drugstore cowboy and promote the legends and lies that are being told as to “How It Really Was “ in the forerunners of the Western movies, the Wild West shows. In the end, it all falls apart, as the people he lived and worked with are gone or moved on to try and survive.

The last scene kind of says it all. Walsh is alone. He’s taking a bead on another one that is outliving his time—a wolf. Once again, he comes full circle. Walsh drops the carbine from his shoulder and asks, “ Did I ever tell you about Big Joe Abernathy? “ But no one is around to hear his story. He’s the last one of his kind, just like the wolf.

—Doc Ingalls of Mesa, Arizona

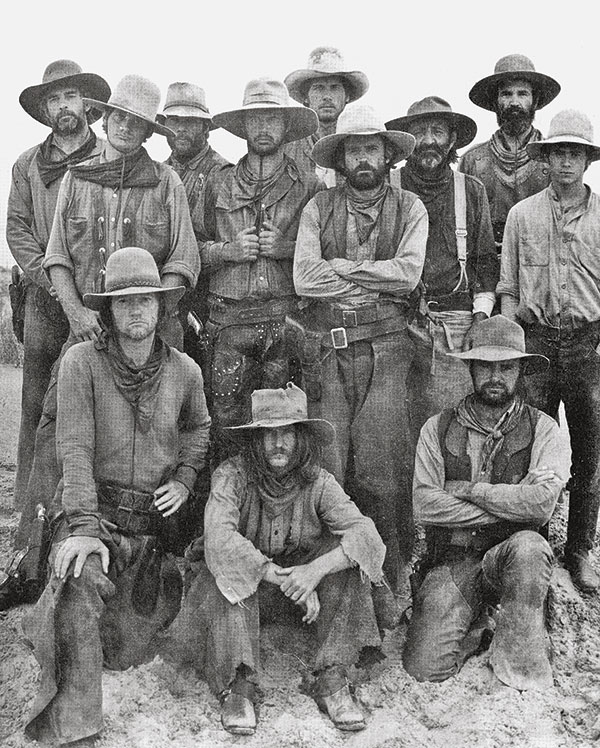

The Culpepper Cattle Co. (1971)

The Culpepper Cattle Co. is the story of a young man’s coming of age during an 1866 cattle drive. The farm boy, played by Gary Grimes, talks a gruff trail boss into giving him a job, but soon finds being a cowboy isn’t the romantic life he imagined. This film provides an accurate portrayal of the bloody, violent post-Civil War period, warts and all.

—Marshall Trimble

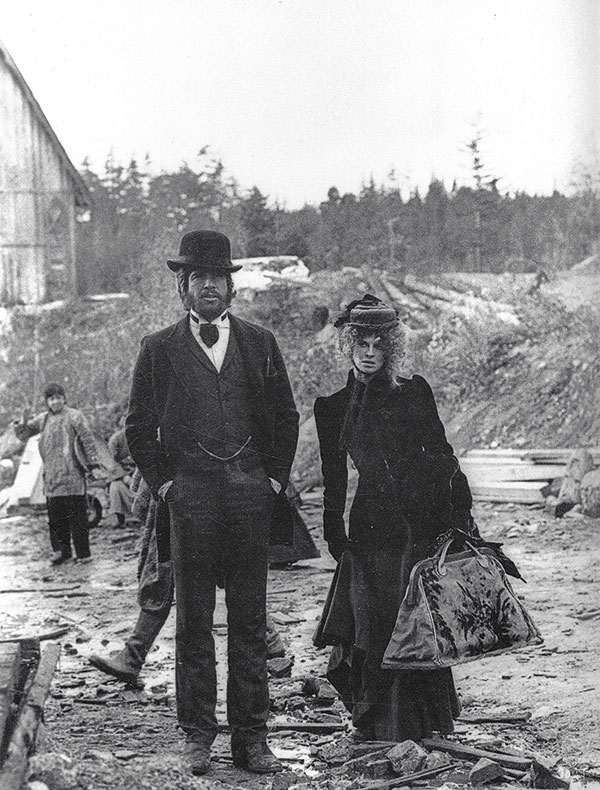

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

The town being built as the movie opens and progresses is quite authentic, showing walls and roofs unfinished, and boards hanging out. I love it when we see McCabe (Warren Beatty) sewing his shirt. Sewing! When is the last time you saw Gene Autry or Hopalong Cassidy or John Wayne sewing?

Then, in the main saloon, people are talking over each other, and you can see their breath! It’s that cold. In fact, what I really love about this Western is the weather: the snow, the freezing conditions and heavy overcoats. For my money, it’s the most authentic weather in a Western ever!

Some Westerns get dinged for having bad hats and incorrect weapons for the times they are portraying, yet the geography is dead on.

—Bob Boze Bell

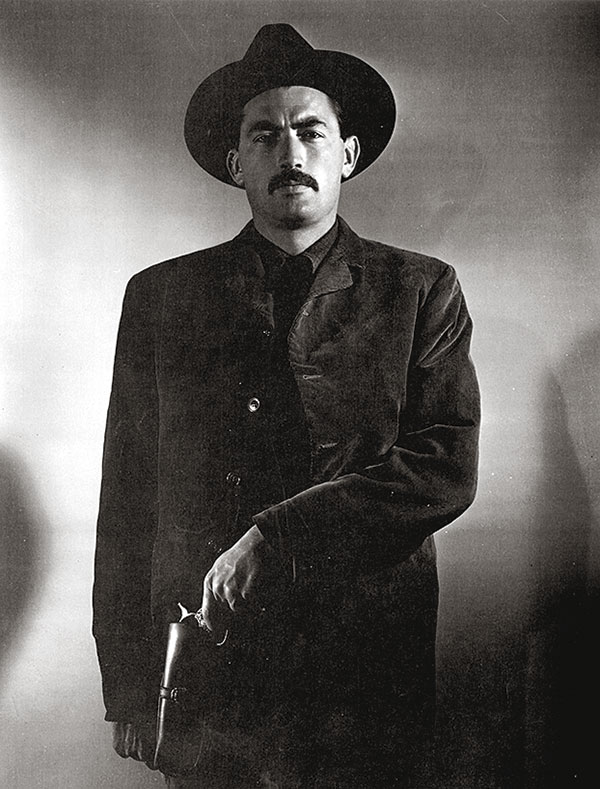

The Gunfighter (1950)

Even if a Western failed on so many levels, the look of one of the main actors could still be just about perfect. Case in point: Gregory Peck, from The Gunfighter. And as one True West Facebook fan pointed out, Skip Jordan, the Western was also taught in college as a “prime example of film dramatization and structure— seven segments of 12-minute scenes, for a total of 84 minutes. Aside from that, it was an unusual character study for a time when Westerns were usually shoot-’em-ups. I think it fit in with the 1952 Westerns Viva Zapata! and High Noon, but is mostly forgotten today.

—Bob Boze Bell

Little Big Man (1970)

Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) meets up with “Wild Bill” Hickok (Jeff Corey) in the saloon. Crabb reaches out his right hand to shake Hickok’s hand as old friends….Hickok grabs Crabb’s right hand with his left hand so that his own right hand is free to reach for his gun “just in case.” A really nice touch, which was probably missed by almost every viewer except those of us who know about Hickok. —Thom Ross

The Iron Horse (1924)

Arguably the master of movie magic was John Ford. In his The Iron Horse, Ford added extra realism by intercutting remote Nevada backgrounds combined with scenes filmed at a half dozen then-underdeveloped sites in California. He knew how to use landscape. One of the most memorable of these was the still impressive segment of the locomotive, which is the real deal and not some 20th-century prop or miniature being hauled through the rugged mountains in Truckee. Despite some of the contrived plot smacking of melodrama, Ford’s The Iron Horse set a high bar for epic Oaters then and now. The silent classic tells a compelling monumental tale on a personal level, as well as demonstrates how the West was made up of all sorts, from many lands and backgrounds, creating a mosaic of types.

—John P. Langellier

Young Guns (1988)

When Young Guns was released in 1988, its Number One opening at the box office was tempered, for me, by a critical bashing that assumed the movie was a contrived Hollywood ploy to put the “Brat Pack on Horseback.” Nothing could have been further from the truth.

I’ve been fairly obsessed with the historical Billy the Kid since I was a kid. It started with the famous tintype photo in a book on gunfighters. That image of Kid Antrim did not seem to square with the popular legends and the movie portrayals fueled by such myth. I wanted to know the unvarnished Kid.

The fact that the young age of the Kid—and many other participants in the Lincoln Wars—lent itself to casting opportunities was just a bonus. The studio saw marketing gold there, but it all started with me and a lifetime fascination with the history.

How that history became myth—even in the Kid’s lifetime—is dramatized some in both Young Guns I and II. Wherever I could get in verified quotes (“many a slip twixt the cup and the lip”) from the historical Kid, I did. The day that we replicated the taking of the tintype, I got into a scrum with the studio over taking too long to get the tintype right. The studio didn’t see what the damn shot represented. For me, and Emilio Estevez, who played the Kid, it exemplified the commitment to authenticity. It was also a full-circle moment for me, as the original and only known photograph of the Kid had started my obsession.

If I was to write the script today, would I do it differently? Today’s audiences are more demanding of historical ballast—and I greatly appreciate that. But then the Neo-Western that became Young Guns would not exist, nor would the fans who developed an interest in the Old West because of it. My proudest moment was hearing Dr. Paul Hutton reference Young Guns as one of the more historically-accurate portrayals of the Lincoln County War.

Recently, with the run of my Netflix series Marco Polo, historian John Man told me something that I think could apply to Young Guns: “As long as you know the true history—which clearly you do—you can wring truth from the facts through dramatization that might not resonate as deeply otherwise.”

—Producer/Screenwriter John Fusco

Ride with the Devil (1999)

In Ride with the Devil, the authenticity of firearms and clothing has never been matched, much less surpassed, in films about the same subject.

Bushwacker or Missouri guerrillas have shown up from time to time in Westerns: Kansas Raiders, with Audie Murphy, as Jesse James; two Randolph Scott efforts, Fighting Man of the Plains and The Stranger Wore a Gun; and The Outlaw Josey Wales, the greatest Clint Eastwood Western, in my humble opinion. Yet, in The Outlaw Josey Wales, an aging John Russell portrays “Bloody Bill” Anderson in a horrible hat and completely unlike the real-life Anderson who looked more like a 1960s rock star. Plus, when the bushwhackers surrender, only Sam Bottoms looks young enough to have been genuine; the rest look to be of an age that the “real deal” never came close to reaching.

In Ride with the Devil, however, the young actors look like the young killers they are playing: long hair, wispy beards, frock coats ,vests, cravats, ties, hats of every variety from the period, multiple revolvers festoon their belts, and the authentic 1851 Navys, 1858 Remingtons, 1860 Armies, a bowie knife and saddles with pommel holsters. Look at historical photographs of these 16- to 20-year-olds and then see their historical reflection in Ride with the Devil. Even the language is very much like the vernacular of True Grit; it’s of another age, with a rustic formality that is true to the time. The locations are wonderfully correct as to the actual killing fields of Missouri: thick brush creek bottoms, woods that green and leaf in the spring and go bare in the gloomy wet winters when the fighting hibernated. Finally, there’s Lawrence, Kansas, sitting out on the rolling prairie, seen from afar.

How did Ang Lee do what no American director never did, or chose not to do?

—Rusty York of Chandler, Arizona

Arizona (1940)

More often than not, Hollywood pays little attention to geography. One backlot is as good as another to represent any part of the West. Not so for Arizona, with all its action filmed in southern Arizona and one of the most realistic movies sets ever created out of adobe hand formed by Tohono O’odham (a.k.a. Papagos) who had been making mud bricks for hundreds of years. Beside building Old Tucson as a convincing stand-in for its namesake of a century earlier, the production added extra details, such as period-correct firearms, not anachronistic Colt “Peacemakers” that never run out of ammunition; a cast of characters sprinkled with names of actual residents of the town in the 1860s; and mostly period-correct costumes, including headgear that even the most rabid “hat Nazi” could not fault.

—John P. Langellier

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

“For one thing, it stayed true to the meticulously researched novel by Ron Hansen. The clothing, guns and settings were all spot on. The acting was superb and location settings also very accurate with the tone of the movie, its characters et al, gripping. There was no romanticizing the lives of the outlaws and the denouement of Bob Ford’s life after killing Jesse, only served to add to the realism of the lives of those men in that time.”

—Billy Brooks of Beverly Hills, Florida

Heaven’s Gate (1980)

Of all the Westerns Kris Kristofferson has acted in, Heaven’s Gate is his favorite.

We can see why; that train scene was breathtaking—hundreds of extras authentically dressed for this train that had to be brought over a mountain in pieces and reassembled for the short sequence.

“I think it was a really beautiful film that got clobbered,” he says. Why did critics beat up on this Johnson County War dramatization, released in 1980? “I think it had to do with our director. It just seemed like that was not an uncommon thing, to get in a film, and all the rivals running it down in the papers and everywhere. And it was so long a production that there was plenty of time to get down on [Director-Writer] Michael Cimino.” —Kris Kristofferson, with commentary from Bob Boze Bell

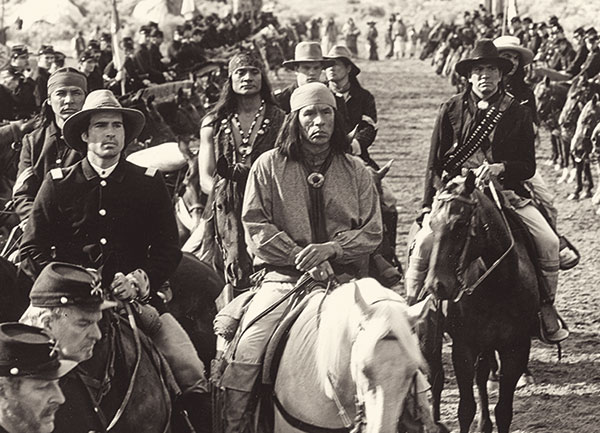

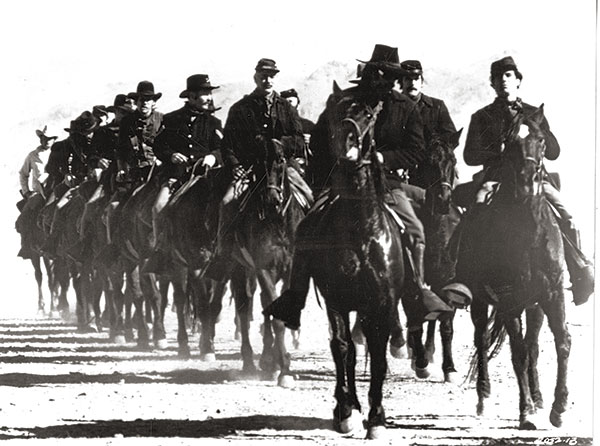

Geronimo: An American Legend (1993)

Hollywood has drawn upon Geronimo more than any other Indian leader—even more than Sitting Bull or Crazy Horse. Walter Hill and John Milius teamed to bring Geronimo’s story to the screen in a visually stunning show that, while uneven, paid considerable attention to many fine points.

For instance, Production Designer Joe Alves, under the guidance of Apache Technical Advisor Michael Darrow, carefully crafted the Apache village, while Costume Designer Dan Moore made certain both Apaches and cavalrymen alike were decked out in the most accurate film renditions ever released. This included superb field uniforms and even one of the only instances of correct 1880s dress uniforms since the silent era.

Even more, Re-enactor Coordinator Riley Flynn made certain his make-believe troopers knew their drills, and their weapons, accoutrements and armaments remain among the best efforts to re-create the look of the last of the Apache campaigns.

—John P. Langellier

The Alamo (2004)

This movie actually tried to follow the history of the battle, including the associated politics of Mexico concerning the empresario system that was used to bring the settlers in. The actors match the actual combatants pretty closely in age (Travis was 26, Bowie, 40, Crockett,50, Houston, 40, Santa Anna, 42). The details for arms and cannons in the mission are very close, as well as the dress of the Texians. The battle is portrayed properly as to the time of day and the probable time that it took to occur.

Even though, this movie did not do well at the box office, I think that is probably because it does not match the popular “mythos” for the battle. It is a pretty accurate portrayal of what the situation must have been like at the siege—a group of cold, trapped, hopeless men caught up in a situation that got out of their control, and who received no relief from their friends on the outside.

—Jarold “Hat” Addington of Florissant, Missouri

Bad Company (1972)

From the opening scene—when boys are shanghaied into fighting in the Civil War, even though they’re trying to escape conscription by dressing as girls—to the scene where the leader of a gang of teenage desperadoes skins a rabbit for the first time, the film is crammed with episodes that startle and enthrall with their realism.

—John Burlinson of Austin, Texas

Ulzana’s Raid (1972)

While the outfits in Ulzana’s Raid are less than perfect, especially for the cavalry, the look and feel of Fort Lowell—including the opening shots of a baseball game on the parade ground, based on serendipity of location scouts seeing a group of re-enactors playing in uniform after one of their drills—was not a typical U.S. Army versus American Indian rehash. The gritty script has no U.S. colors flying over a column of hundreds of horse soldiers as they charge with sabers. Instead, a small patrol doggedly follows a frustrating trail of an equally determined and frankly more-savvy Apache enemy.

While brutal, the picture is no Sam Peckinpah bloody ballet of carnage. As for Burt Lancaster, he nails the white frontier scout modeled after Al Sieber, a literary figure who could be traced back to James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking model. In a way, Lancaster had a bit of a dress rehearsal for the role, playing the title character in Valdez is Coming from the previous year.

—John P. Langellier

The Big Trail (1930)

While not known for attention to detail in later films, John Wayne’s major film debut in 1930’s The Big Trail proved a notable exception. His incredible “Kentucky” long rifle, stellar buckskin outfit, great backgrounds (from scenery to the wagon train) and camp equipment all made this picture notable. Unfortunately the film flopped at the box office, condemning the Duke to poverty row and Six-Day-Westerns, until the actor was reprieved nine years later by John Ford’s Stagecoach. —John P. Langellier

The Last of the Mohicans (1992)

Daniel Day-Lewis nailed Hawkeye in 1992’s The Last of the Mohicans based on James Fenimore Cooper’s novel. Lewis’s exquisitely crafted La Longue Carabine (nickname for the marksman, which translates as “The Long Rifle”) and the movie’s letter-perfect 18th-century siege, faithfully rendered French and British battle flags and a host of other carefully crafted visuals raise this eastern Western to heights seldom seen in cinema. —John P. Langellier

How the West Was Won (1962)

Although the sprawling How the West Was Won was more Hollywood than history, the 1962 film offered many momentary glimpses into the everyday life of the daring pioneers who made their way across the continent. For instance, the wagon train encampment rivaled some of the best the silver screen had to offer, as did the buffalo hunter portrayed by Henry Fonda and the “hell on wheels” railroad scenes harkening back to 1924’s The Iron Horse. —John P. Langellier