— All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell unless otherwise noted; Headline Design by Bob Steinhilber —

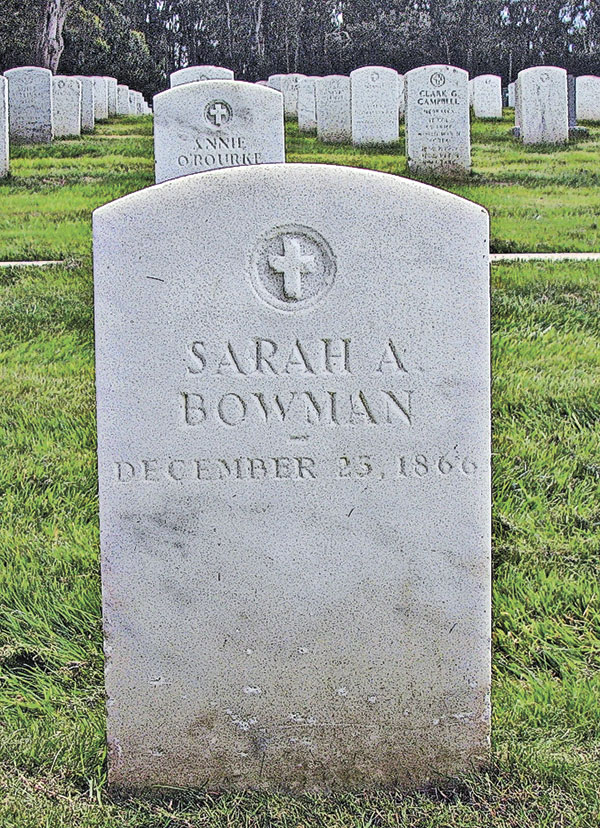

In late August 1890, a detachment from the U.S. Army Quartermasters Department began the arduous task of exhuming the bodies of the soldiers in the long abandoned and overgrown Fort Yuma cemetery to be reburied at the Presidio in San Francisco, California.

Of the 159 bodies disinterred, only one was that of a woman, yet it was the largest of all the remains. Around her neck was an oversized Catholic medallion. This was the body of Sarah Bowman—the Great Western.

The Heroine of Fort Brown

Sarah was born in either Tennessee or Missouri in 1812 or 1813 (the records are contradictory), and her maiden name was long ago lost to history. An impressive woman over six feet tall and close to 200 pounds, she was blessed with a well-proportioned, if ample, hourglass figure and an attractive face framed by dark red hair.

Sarah had a great appetite for life…and for men. She married at least four times. The name of her last husband, a German immigrant in the 2nd Dragoons who was 10 years her junior, stuck with her.

Private Sylvester Matson, impressed by Cpl. Albert Bowman’s bride, wrote in his diary on May 9, 1852: “Today we are reinforced by a renowned female character. They call her doctor Mary. Her other name is the Great Western.”

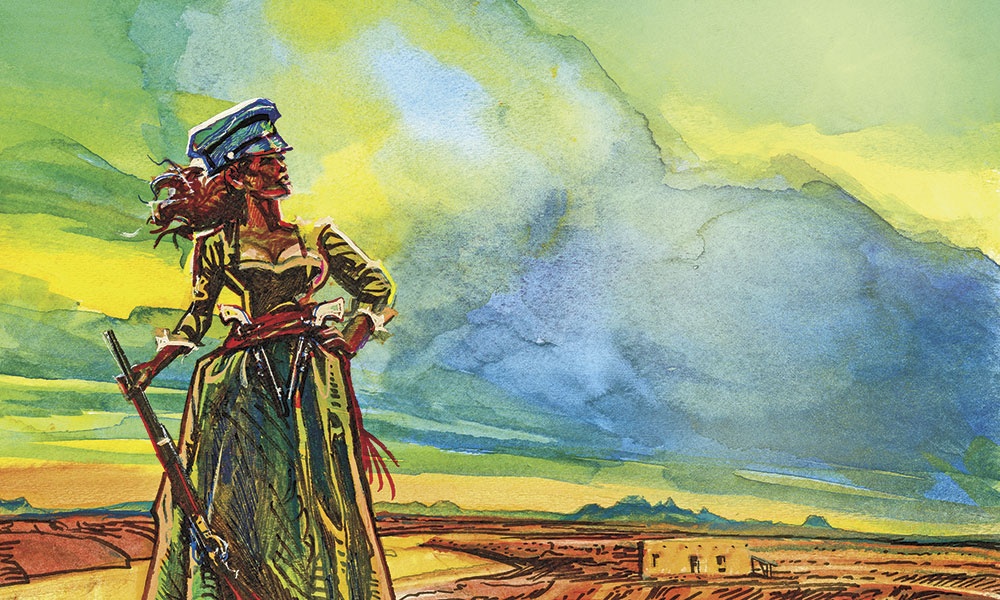

Matson described her as a “giantess over seven feet tall,” with a scar across her cheek from a Mexican saber wound. The camp story claimed that she had killed the Mexican soldier who wounded her.

“She appears here modest and womanly not withstanding her great size and attire. She has on a crimson velvet waist, a pretty riding skirt and her head is surmounted by a gold laced cap of the Second Artillery. She is carrying pistols and a rifle. She reminds me of Joan of Arc and the days of chivalry,” Matson wrote.

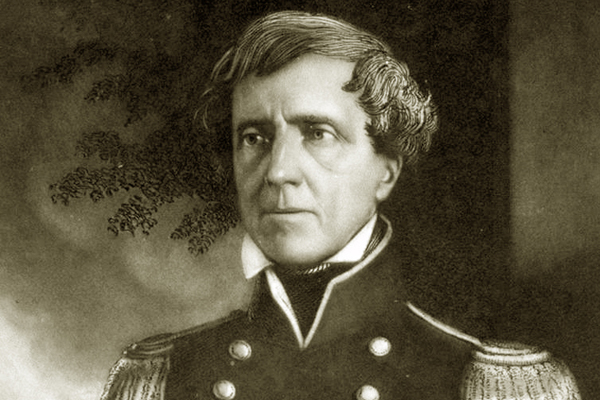

She claimed Lt. George Lincoln signed her on as a laundress at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri and that she accompanied her first husband (name unknown) to Florida during Col. Zachary Taylor’s Seminole campaign. This had to be after 1837, since Lincoln was not commissioned until late that year. Sarah developed a keen affection for the young 8th Infantry officer from Massachusetts.

— Courtesy West Point Museum Collection, United States Military Academy —

Her fame, however, was not derived from military life in the Florida swamps, but rather from her heroics during the Mexican-American War. Her second husband, Charles Bourgette of the 5th Infantry, was among the troops assigned to occupy the Nueces Strip in Texas just before the outbreak of the war. This disputed land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande was claimed by both Texas and Mexico. Sarah worked as a laundress and cook attached to Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army when it reached Corpus Christi in July 1846. When her husband became ill and was evacuated to Point Isabel on the coast, she drove her wagon south to the Rio Grande.

A Mexican officer sent the Americans an ultimatum not to cross the river unless they wished war. Hearing of this, Sarah declared to those around her that “if the general would give her a good strong pair of tongs, she would wade that river and whip every scoundrel that dare show himself.”

The Mexicans withdrew before Sarah could secure her pair of tongs (pantaloons). Taylor reached the Rio Grande on March 28, 1845, and immediately ordered the construction of earthen fortifications across the river from Matamoros in Tamaulipas, Mexico.

The general left the 7th Infantry under Maj. Jacob Brown to finish construction, while he took his main force to Port Isabel to secure his line of supply. Sarah remained with the 7th. By this time, she had already been nicknamed the “Great Western,” which was, at the time, the name of the largest steamboat in the world.

On May 3, the Mexicans opened a fierce bombardment of the post. Major Brown’s guns replied. For five days and nights, the Mexican shells rained down on the American fort. Brown fell on the fourth day, a shell exploding just above his position.

The experience was a living hell for all the defenders. Yet the Great Western refused to take shelter with the other women. She set up her kitchen tent in the middle of the fort and kept the men on the walls fed, despite a bullet dislodging her bonnet. She also took water to the parched soldiers and tended to the wounded until Gen. Taylor lifted the siege on May 9, crushing Gen. Mariano Arista’s force at Resaca de la Palma.

On May 18, the American army crossed the Rio Grande to occupy Matamoros and prepare for the invasion of northern Mexico. A grand dinner party was held in Gen. Arista’s elegant headquarters in Matamoros, with Sarah as a special guest. Lieutenant Braxton Bragg offered a toast that was met with cheers from all the officers to the “Great Western—one of the bravest and most patriotic soldiers at the siege of Fort Brown.”

Newspapers around the country quickly picked up on the story of this “heroine of Fort Brown.”

Devotee to “Old Rough and Ready”

When Taylor’s army moved west against Monterrey, the Great Western followed. Taylor was Sarah’s kind of general, a man who inspired her to walk into battle so she could feed the troops and care for the wounded. The soldiers had affectionately nicknamed the future President “Old Rough and Ready” for he was always quick to share their privations, discomforts and dangers.

The general habitually kept a quid of tobacco tucked in his cheek and impressed all with his ability to hit a target with one spit. As a frontier soldier, he cared little for military pomp, leading one officer to describe him as “short and very heavy, with pronounced face lines and gray hair, wears an old oil cloth cap, a dusty green coat, a frightful pair of trousers and on horseback looks like a toad.”

“Old Rough and Ready” may have not looked much like a soldier, but he was a fighter, and Sarah admired him as such. During the Battle of Buena Vista, on February 23, 1847, a panicked soldier rushed back among the reserves, crying out that Taylor was whipped and the Army destroyed. Sarah seized the man, and “she just drew off and hit him between the eyes and knocked him sprawling; says ‘you damned son of a bitch, there ain’t Mexicans enough to whip old Taylor,’” Texas volunteer George Washington Traherne reported.

Lincoln, the man who had welcomed Sarah into the Army, met his death in Buena Vista. She was devastated by the news and fell weeping into a chair. Composing herself, she rushed to the field to retrieve the captain’s body and bring it back to Saltillo for burial. She later purchased Lincoln’s white horse at auction, offering three times the high bid for the animal so that the proceeds could be sent home to the captain’s mother. She rode the horse during the rest of the campaign and then arranged for it to be sent to Massachusetts for the Lincoln family.

In Saltillo, she had opened an establishment—American House—that catered to the many needs of the army of occupation. It became a sort of informal headquarters for Army officers. Her husband had long since vanished, and Sarah provided some of the most sought after services herself. Traherne left an indelible pen picture of her statuesque charms when he commented: “you can imagine how tall she was, she could stand flat footed and drop those little sugar plums right into my mouth.”

The Biggest Leg in Mexico

When the war ended and the Army moved north from Saltillo, Sarah appeared on horseback followed by three large wagons, only to be informed by a blue-nosed, by-the-book officer (Daniel Rucker, later quartermaster general and father-in-law to Phil Sheridan) that without a husband, she could not join the column.

“All right Major, I’ll marry the whole Squadron and you thrown in but what I go along,” she declared. She gave the officer a smart salute and turned her horse to trot down the line of soldiers.

“Who wants a wife with $15,000, and the biggest leg in Mexico!” she cried out. “Come my beauties, don’t all speak at once—who is the lucky man?”

A dragoon named Davis volunteered for this hazardous duty, if a clergyman could be found “to tie the knot.” Sarah replied with a laugh: “Bring your blanket to my tent tonight and I will learn you to tie a knot that will satisfy you, I reckon.”

Sarah soon had a new husband and an official place on the rolls of the dragoons as laundress.

As soon as convenience allowed, Sarah ditched Davis and moved her thriving business north to El Paso del Norte, where, in April 1849, she set up shop on the American side of the river in partnership with a trader named Benjamin Franklin Coons. Their Central Hotel became the first business in the town called Franklin, but which became El Paso, Texas.

Famed Texas Ranger John “Rip” Ford met Sarah at her hotel. “On our side an American woman known as the Great Western kept a hotel. She was very tall, large and well made,” Ford related of his 1849 encounter. “She had a reputation of being something of the roughest fighter on the Rio Grande. She was approached in a polite, if not humble, manner by all of us.”

Sarah left El Paso late in 1849 for Socorro, New Mexico Territory, where she appeared in the 1850 census as Sarah Bourjette, age 33, birthplace Tennessee, and noted as illiterate. With her was a family of five orphaned children, the Skinners, who she had taken in. One of them, Nancy, would remain with Sarah for the rest of her life and always referred to her as mother. Over time, Sarah also adopted several Hispanic and American Indian children.

Life in Fort Yuma

In Socorro, Sarah met an immigrant soldier of the 2nd Dragoons named Albert Bowman. They married, and the couple stayed together for the next 16 years.

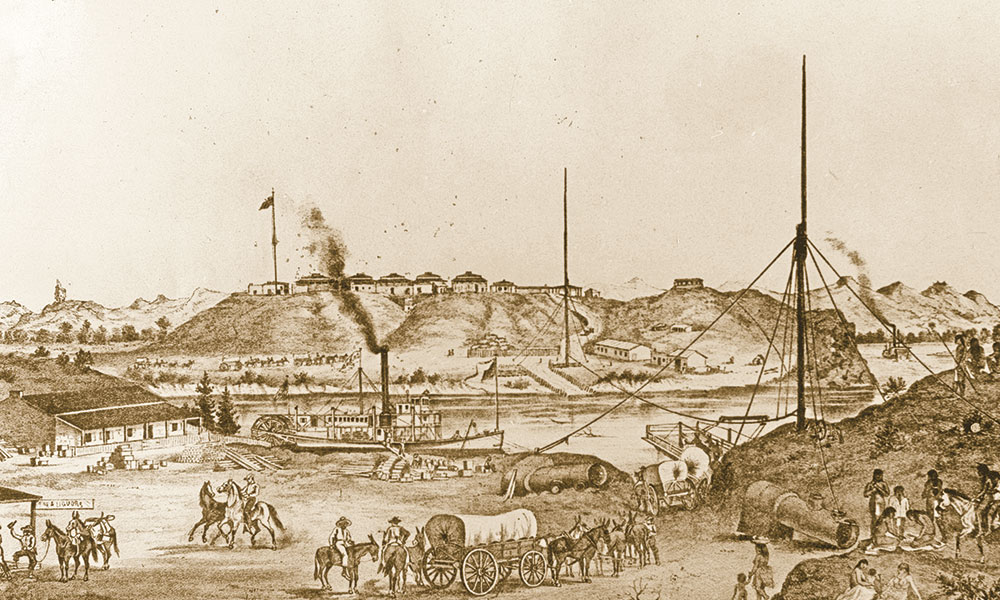

Bowman departed military service from Fort Webster in New Mexico Territory on December 1, 1852, and he and Sarah soon headed west toward California. They stopped at Fort Yuma at the Colorado River crossing where Sarah’s fame secured her an immediate position serving the officer’s mess at the post while Bowman found work as a carpenter.

Captain Samuel P. Heintzelman, the post commander, took note of the Bowmans’ arrival in his diary entry for October 10, 1853: “The Great Western called to see me to get some tires reset. I could not refuse when I recollected her services. She was at Fort Brown and 20 years in the army and once in my Company. She looks 50 is a large tall fearless looking woman.”

Sarah called on the captain for help again, sharing her tale of woe concerning her adopted daughter Nancy Skinner who she claimed California authorities planned to take from her. Heintzelman assisted Sarah with supplies and building materials in order to build a home in the future Arizona Territory, across the Colorado River, in Sonora, where Nancy would be safe from the California lawmen.

Nancy, who was 16, soon married an ex-soldier who had followed her to the Yuma Crossing from New Mexico Territory. The good captain came to realize that he had been hoodwinked into helping the Great Western build a home for herself.

Sarah’s new establishment across the Colorado River fed the varied appetites of Fort Yuma’s officers and enlisted men, as well as the hundreds of travelers who crossed the river on Louis Jaeger’s ferry. In time, a village grew up around her combination dance hall, restaurant and brothel, first called Colorado City and finally Yuma. Charles Poston and Herman Ehrenberg surveyed the town site in July 1854 on their return journey to California from their exploration of the Gadsden Purchase in southeastern Arizona Territory.

Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry, soon to be another of the founding fathers of Arizona, was one of Sarah’s most ardent admirers. “I have just got a little Sonoran girl for a mistress,” he wrote a Rhode Island friend in 1855.

“She is seventeen very pretty [and] for the present she is living with ‘The Great Western’ you remember don’t you, is the woman who distinguished herself so much at the Fort Brown bombardment just before the battles at Palo Alto and Resaca. She has been with the Army twenty years and was brought up here where she keeps the officers’ mess. Among her other good qualities she is an admirable pimp. She used to be a splendid looking woman and has done ‘good service’ but is too old for that now.”

Olive Oatman’s Safekeeper

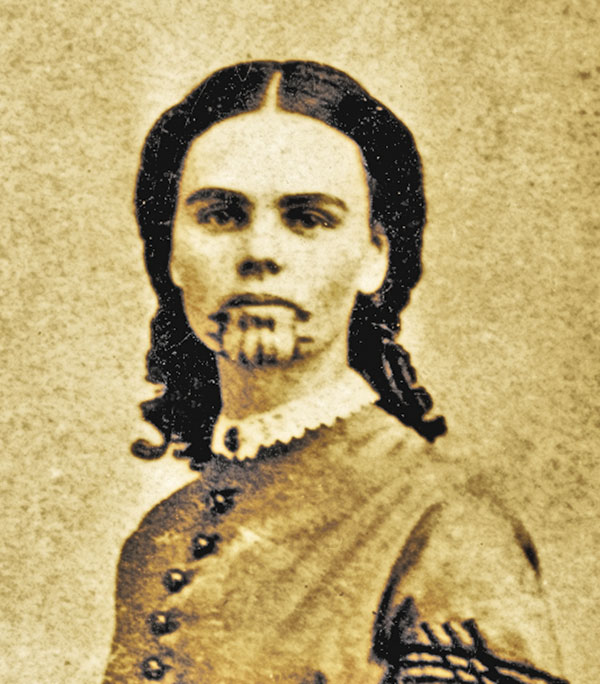

Despite Sarah’s profession, or perhaps because of it, when Olive Oatman was ransomed from the Mohaves and brought to Fort Yuma on the last day of February 1856, she was turned over to Sarah for safekeeping. Olive was wild with fear and anxious to return to her Mohave family.

The nine members of the Oatman family had been traveling westward along the Gila River toward California when a party of Yavapai warriors attacked on March 19, 1851. The Yavapais are Yuman speakers, related in the distant past to the Mohaves and Walapais, but because they ranged north into central Arizona, they were often mistaken for Apaches by the whites. The Spanish called the Yavapais by three distinctly different names, the Americans by two names and the neighboring tribes by six different names. Little wonder that the confusion over the Yavapais resulted in the Apaches being universally blamed for the Oatman family killings. Royce and his wife Mary, along with four of their children, were murdered. The Yavapais left a 15-year-old son, Lorenzo, for dead, while carrying off 14-year-old Olive and seven-year-old Mary into slavery.

The Yavapais sold the girls to their Mohave cousins, who took them to their village along the Colorado River. Mary starved to death, but Olive survived to grow into an attractive young woman who became quite acculturated to her new life, even participating in a tattooing ritual that left her chin permanently marked with native designs.

After five years, Olive was ransomed by a Fort Yuma carpenter and his Yuma Indian friend, and brought into the post. She had forgotten English. The officers feared for her sanity, but under the tender care of the Great Western, she was soon communicating well and anxious to be reunited with her long lost brother, Lorenzo.

After the massacre, two Pima Indians had found Lorenzo and taken him to Fort Yuma where he had begged the soldiers to go in search of his sisters. Captain Heintzelman refused to send out a search party since he barely had enough men to garrison and guard the fort.

By now, Lorenzo was living in El Monte, California. He rushed to Fort Yuma upon receiving word of his sister’s rescue. “She did not know him and he did not know her also,” remarked an eyewitness to the reunion, “so much change in five years.”

Sarah would be facing considerable change herself. As she watched Olive depart for her new life as a celebrated “redeemed captive,” Sarah was preparing to depart Yuma for Tucson.

Graydon’s Girls

In October 1856, Sarah and Albert joined a small wagon train headed east, happy to leave Yuma behind. “There was just one thin sheet of sandpaper between Yuma and Hell,” she declared, upon departing the desert metropolis she had founded.

Along the Gila Trail, Sarah halted the wagon train long enough to give the victims of the Oatman massacre a decent burial.

Upon her arrival in Tucson, Sarah operated a boarding house, but soon decided to relocate to the Sonoita Valley to be closer to the new Fort Buchanan. She formed a fresh business partnership, and by the summer of 1858, she and her girls were well established with James “Paddy” Graydon at Casa Blanca.

An Irish immigrant and ex-dragoon, as well as one of the most colorful characters in the Southwest, Graydon owned the United States Boundary Hotel, located along Sonoita Creek, just four miles south of Fort Buchanan. The one-story adobe was known to all as Casa Blanca because of its whitewashed walls. Graydon advertised his hotel’s “fine assortment of wines, liquors, cigars, sardines…and good accommodations for the night.”

At the hotel, Sonoran señoritas sang songs, waited tables and cooked, sometimes dealt cards, and always smiled at the rough patrons, laughed at their crude jokes and helped them to forget just how very far from home they were. The hotel, remarked one patron, was a “pretty tough joint, but a good saloon.”

Guns and knives often settled disputes over cards, for as Lt. Isaiah Moore of the dragoons commented, the “American population” on the Sonoita was “mostly outlaws having everything to gain and nothing to lose.”

Graydon’s most profitable venture was likely the partnership he formed at Casa Blanca with the most famous woman on the frontier—Sarah Bowman.

Word quickly spread of Sarah’s arrival at Casa Blanca. Jeff Ake, who met her at Graydon’s place in 1856, was awestruck: “They called her old Great Western. She packed two six-shooters, and they all said she shore [sic] could use ’em, that she had killed a couple of men in her time. She was a hell of a good woman.”

Ake’s father, Grundy, spoke of Sarah reverently as simply the “greatest whore in the West.”

Sonoran ladies by the score came north to work for Paddy and the Great Western. “Sonora has always been famous for the beauty and gracefulness of its señoritas,” Poston remarked. He remembered that they “really had a refining influence on the frontier population. Many of them had been educated at convents, and all of them were good Catholics.”

The Americans both amused and disgusted the señoritas. “They called the American men ‘Los God-dammes,’ and the American women ‘Las Camisas-Colorados,’” Poston noted. “If there is anything that a Mexican woman despises it is a red petticoat.”

While some of the Sonoran maids and grass widows may have been repulsed by the Great Western and her girls, others happily joined in the fleecing of soldier and miner alike. They found work as cooks at mines and ranches. Some landed husbands, while others served drinks and food, sang songs and ran the gambling tables at Casa Blanca.

“They were experts at cards,” Poston recalled from sad experience, “and divested many a miner of his week’s wages over a game of Monte.”

The valley was troubled by a turbulent group of young toughs led by Bill Ake, which a later generation would label with the epithet “cow-boys.” They terrorized the local Hispanics, and Graydon had to establish some sort of law and order in the valley.

After two Mexicans were killed in a saloon brawl with the cow-boys at Casa Blanca, Graydon had a gunfight with one of the drunken toughs. In time, Graydon set himself up as a sort of an informal lawman and drove out the outlaws. The Army also paid him a monthly salary to act as a scout and interpreter when needed. Much of this work involved trailing deserters and bringing them back to the fort, and Graydon made quite a reputation for himself in this work.

Yet the outlaws or the deserters were not the ones who most troubled the valley, but rather the secessionists and the Apaches. The kidnapping by Aravaipa Apaches of a local rancher’s stepson—Felix Ward (a.k.a. Mickey Free)—had led to a war between the Chiricahua bands of Cochise and Mangas Coloradas and the whites in January 1861. The outbreak of the Civil War in April sealed the valley’s fate.

On July 9, 1861, an express reached Fort Buchanan with orders to abandon the post and march to Fort Fillmore along the Rio Grande. Lieutenant Moore soon arrived with his two dragoon companies from the abandoned and burned Fort Breckenridge to join the two companies of the 7th Infantry on their eastward trek.

As the troops departed on July 23, they torched the fort and all the supplies they had left behind. Even Graydon was not allowed any government goods, for orders were orders, and the government wanted all property destroyed rather than turn any over to the citizens of Arizona Territory. In some ways, the government feared the citizens, and their secessionist sympathies, more than the Apaches.

“Well, this country is going to the devil with railroad speed,” reported journalist Thompson Turner from Tucson on July 17. “Secessionists on one side and Apaches on the other will bring us speedily to the issue, and the issue will be absence or death.”

The game was up, and the Americans along the Sonoita and Santa Cruz packed up and left their fields. Most of the Mexican mine and ranch workers fled south to Sonora. To make matters worse, Mexican bandits came north to loot the abandoned mines and ranches. Only Sylvester Mowry, with 100 heavily armed men, held out at his Patagonia mine.

Poston, with Raphael Pumpelly and a black servant, also finally gave up on his Arizona dream and headed for Yuma. Poston was struck by the lonesome sound of cocks crowing on the deserted farms as smoke from the burning wheat fields filled the sky. “It was sad to leave the country that had cost so much money and blood in ruins, but it seemed to be inevitable,” Poston later wrote, “but the greatest blow was the destruction of our hopes—not so much of making money as of making a country.”

The largest exodus from the “Purchase” was led by old Grundy Ake and his friend William Wadsworth. Driving all the cattle of the Sonoita with them, they reached Tubac on July 20. With them was Sarah. Graydon had decided to abandon Casa Blanca, for the clientele had left. With no one left to purchase the services that the Great Western’s girls provided, Sarah sent her girls south to Sonora and parted with the eastbound Graydon.

The flamboyant Irishman joined the Union Army and soon raised a company of Hispanic scouts who harassed the invading Confederates under Henry Hopkins Sibley. A hero of the 1862 Battle of Valverde, Graydon then served under Col. Kit Carson against the Mescalero Apaches before being killed in a senseless gunfight on the Fort Stanton parade ground.

Acts of Tenderness

The Great Western once again headed westward. She and her people traveled with the Ake-Wadsworth wagon train to Tucson, but then headed back to the Yuma Crossing. The crew made the trip safely, and Sarah and Albert were soon well established in their old house on the Arizona side of the Colorado River.

Poston and Pumpelly arrived in Yuma to find Sarah back in business. They boarded with her, and Pumpelly, who later became a famous explorer and Harvard professor, was mesmerized.

“Our landlady, known as the ‘Great Western,’ no longer young, was a character of a varied past,” Pumpelly wrote in his memoir. “Her relations with the soldiers were of two kinds. One of these does not admit of analysis; the other was angelic, for she was adored by the soldiers for bravery in the field and for her unceasing kindness in nursing the sick and wounded.”

The Eastern dude watched this magnificent woman’s every movement “as with quiet native dignity, she served our simple meal. She was a lesson in the complexity of human nature.”

California volunteers soon flooded into Fort Yuma to prepare to march east against the Confederates. Sarah once again did a booming business, although in a new house, since the first had washed away in a flood that winter.

Lieutenant Edward Tuttle was suitably impressed. “She was a splendid example of the American frontier woman,” he gushed. He was also impressed that the 4th Infantry had awarded her “rations for life.”

Those rations did not continue for long. Sarah died on December 23, 1866, at Fort Yuma, in her 53rd year, the victim of the bite of a tarantula spider. Soldiers buried her in the Fort Yuma cemetery, where they fired a salute over her grave. She was the only woman buried there amidst all the soldiers.

Prescott’s Arizona Gazette mourned her passing with a tardy obituary on July 31, 1867: “She was familiarly known as the ‘Heroine of Fort Brown,’ and was at several battles during the war, caring for the wounded. Blunt and unguarded in speech, she was yet the possessor of a kind heart, and whatever her failings, engendered by wild associations, very many will remember with grateful feeling the acts of tenderness bestowed by her on themselves and associates in that inhospitable section…. And as this mention of the decease of the ‘Great Western’ meets the public eye, how many minds will revert to the frequent acts of kindness performed by this distinguished female representative of American frontier life.”

The Golden Gate’s Gal

In 1890, soldiers exhumed the bodies at the abandoned Fort Yuma cemetery and reburied them at the Presidio in San Francisco. The Great Western now rests at the very end of the westward trail, overlooking the Golden Gate. Her grave above San Francisco Bay is marked with the same simple white stone reserved for all the heroes of the republic.

A Distinguished Professor of History at the University of New Mexico, Paul Andrew Hutton won the Western Writers of America Spur for his most recent book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History.