An on-the-scene account you’ve likely never heard until now.

Perhaps the best known photo of a woman bronc riding is the 1915 image of Bonnie McCarroll by rodeo photographer Ralph Doubleday. Bonnie is shown upside down, ringlet curls flying as her head nears the hard-packed grass of Oregon’s Pendleton Round-Up arena for a landing that looks as if it could be a serious one. The bronc, a bay called Silver, is high in the air, shown mid-buck, ragged hooves flying.

A remarkable feature of the photo is the presence of a rope hobble, tied to the left stirrup of Bonnie’s bronc saddle, apparently broken or severed. Rope hobbles were used by some lady bronc riders as a way of tying the stirrups together, making it possible for a rider to wrap her legs around a bronc and ride out the storm. Free stirrups allowed the rider to rise and fall, spurring with each buck. Yet when a rider secured her feet in the tied-together stirrups, she was more or less locked into the saddle. Since one must fall “up” to fall off, the “up” was not as easy when the top of the foot could lock against the top of the stirrup.

In that same Pendleton arena, in 1929, Bonnie made her final rodeo appearance, intending to retire, with her husband, Frank, following the roundup. Bonnie was 34 years old that September 19. She’d drawn the proven bronc Black Cat for her first ride. In some rodeos, lady riders had a choice between hobbled stirrups or “slick” riding, but at the 1929 Pendleton Round-Up, the ladies were required to ride hobbled.

Though a fair number of eyewitness accounts are recorded, perhaps the most accurate and chilling was by former rodeo clown Monk Cardin, a 19-year-old who knew the sport. Cardin was, by his account, near Bonnie and Black Cat as she mounted.

Important to the accuracy of the account was Cardin’s ability to see as an experienced rodeo participant sees an accident. When a rodeo neophyte witnesses a rider taking a spill, he might say, “The rider was thrown from a wild, vicious bucking bronco.” A knowledgeable rodeo person, however, might say, “He drew an honest horse that would have scored him in the high 70s, did not score well out of the gate and shook loose the second jump. He let himself get yanked forward and didn’t recover. He made about five seconds, and then he tipped off the right side.” Big difference in the description, right?

Cardin reports that Black Cat was agitated that day. Just as Bonnie nodded for the snubber to release her for the ride, Black Cat flipped over backwards, crushing her. With Bonnie locked into the saddle by her hobbled stirrups, the bronc jumped up, took a stumbling half jump and somersaulted forward, headfirst landing on the rider again. He clamored up and started bucking across the arena, with Bonnie still in the saddle.

She was knocked out cold, possibly already beyond help, and no longer had the bronc rein in her hand. The pickup rider rode alongside, trying to get hold of the rein to no avail. He reached for Bonnie’s arm, making a desperate attempt to pull her free, and almost succeeded. As he pulled her from Black Cat, her foot rotated, jamming her toe against his side and effectively caught her in one stirrup, which was still hobbled tightly to the other stirrup, under the bronc’s belly.

Black Cat continued to buck the length of the arena as Bonnie dangled beneath him by one stirrup, her head hitting the hard-packed grass arena with every jump. Her boot finally shook loose, and she came off. Cardin recounted that the spectators fell eerily silent as Bonnie’s husband, Frank, rushed to her side. He picked up the limp Bonnie, carried her to a waiting automobile, and she was rushed to the hospital.

The stands cleared out following the awful incident, Cardin said in a 2009 interview (when he was 100 years young). It was obvious to everyone who witnessed the wreck that Bonnie had met her end, by way of insurmountable injuries.

She passed in the hospital on September 29, 1929. The rodeo world mourned the loss of a beloved member, and women’s bronc riding was never again included in the Pendleton Round-Up. Perhaps Bonnie’s most commonly known legacy, though, is that famous photo, taken 14 years prior to her death, which eerily foretold what would become of her.

True West Archives

True West Archives

Juni Fisher is an award-winning singer, whose latest album, Let ’er Go, Let ’er Buck, Let ’er Fly, commemorates the Pendleton Round-Up centennial. In the summer of 2009, she tracked down this 100-year-old former rodeo clown, four months before his death, after digging through the archives at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

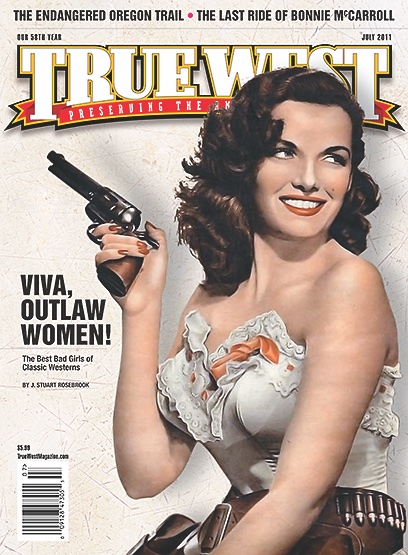

Editor’s Note: Award-winning singer-songwriter Juni Fisher, a friend of and contributor to True West for many years, is also a noted folklorist of the Old West. If you’d like to read more of Fisher’s articles like “The Last Ride of Bonnie McCarroll” from the July 2011 issue, please go to TrueWestMagazine.com and subscribe for full access to more then 67 years’ worth of exciting issues of True West.