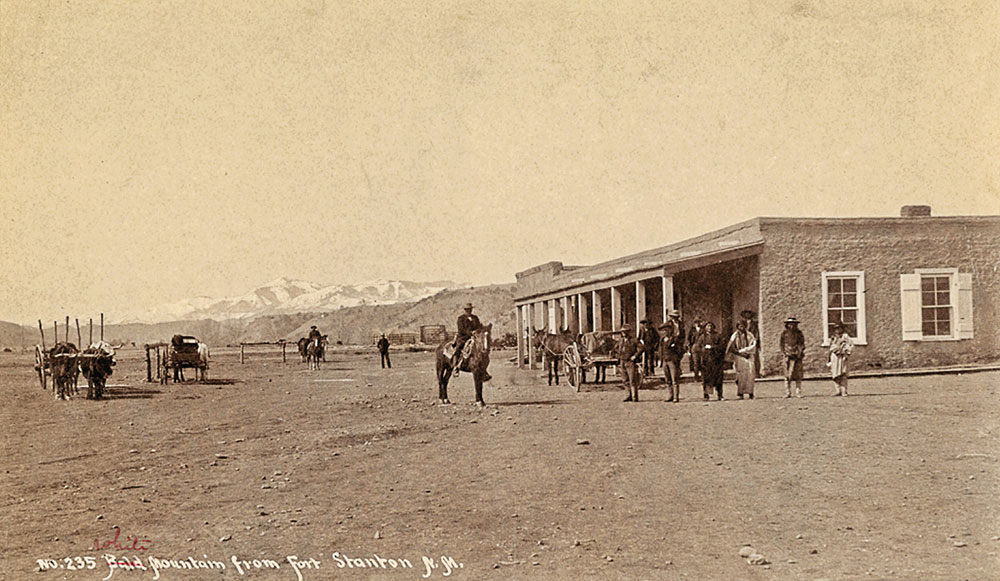

— Courtesy Lynda A. Sánchez Collection —

Like a hive of angry wasps!

The Apaches were more than fighting mad over the white men invading their country. Their reaction was like hurling a spear into a huge hive of angry wasps.

Of course, the Mescaleros were trying to protect their lands and especially their families. As later reported, near the Stanton death site, many lodges (tipis) were found abandoned as the Mescaleros fled their winter camps for rougher and safer country in the rugged Guadalupes on the New Mexico/Texas border. That, too, was Apache country. There, they took refuge and were safe for a while as the war-weary group of Dragoons and Infantry retreated to Fort Fillmore. So much for a Dragoon’s duties being “more pleasant than those of other regiments.”

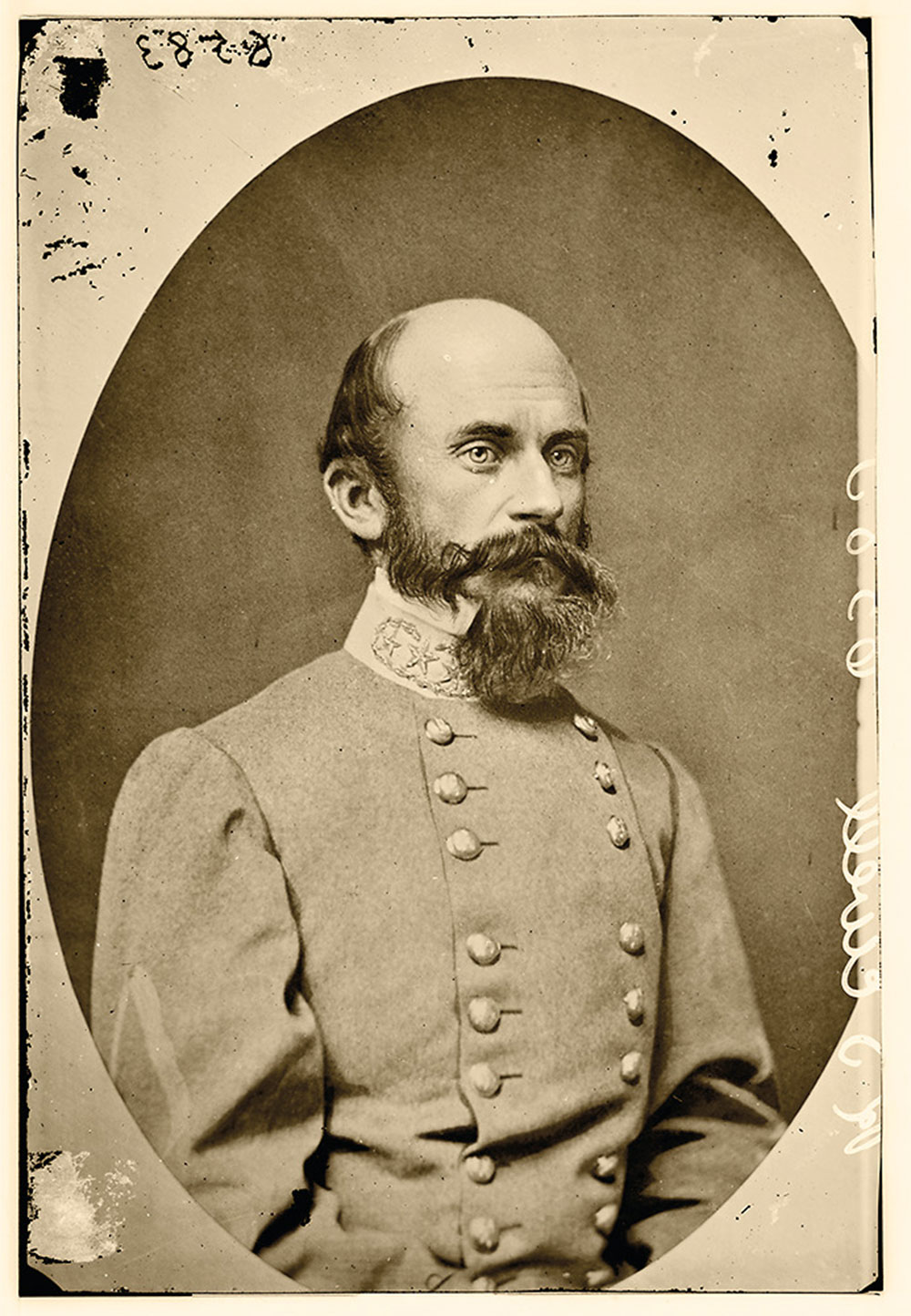

“Very flattering accounts are given of the First Dragoons,” wrote Capt. Richard Ewell. “Their duties are said to be more pleasant than those of most other regiments of the service, and the officers are reported to be some of the best specimens of the army.”

Captain Henry Whiting Stanton was one such proud Dragoon. He was excited about serving his country out West.

Stanton came from a family tradition of service to his country. He was the son of Gen. Henry Stanton and Eliza Keyes. When he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps, it must have greatly pleased the general. Graduating from West Point on July 1, 1842, he saw duty on the frontier at several forts including Forts Towson, Gibson and Leavenworth. He fought with the First Dragoons during the 1846 War with Mexico and was soon promoted to first lieutenant. Stanton was stationed in California, Oregon, Kansas and Missouri. In 1854 he was promoted to captain and posted to Fort Fillmore, near present-day Las Cruces, New Me xico.

Fort Fillmore can barely be seen today as its adobe walls have crumbled into nothingness near the Rio Grande. Founded in 1851 and decommissioned in 1862, it continued to be used for the Butterfield stage line and a few settlers until the 1870s. As with many forts of that era, it was established to protect the settlers from the ravages of Apache and outlaw attacks. It also was considered to be a way station along the route to California because Westward expansion was just beginning. Being located close to the Mexican borderlands, it was always in a state of turmoil. Captain Stanton was assigned here in 1854 and it was the fort to which his body was returned in February of 1855. Falling into disrepair after the late 1850s the fort briefly saw a flurry of activity during the early part of the Civil War. Abandoned to the Confederate forces for a while, this rather drab fort was decommissioned in 1862.

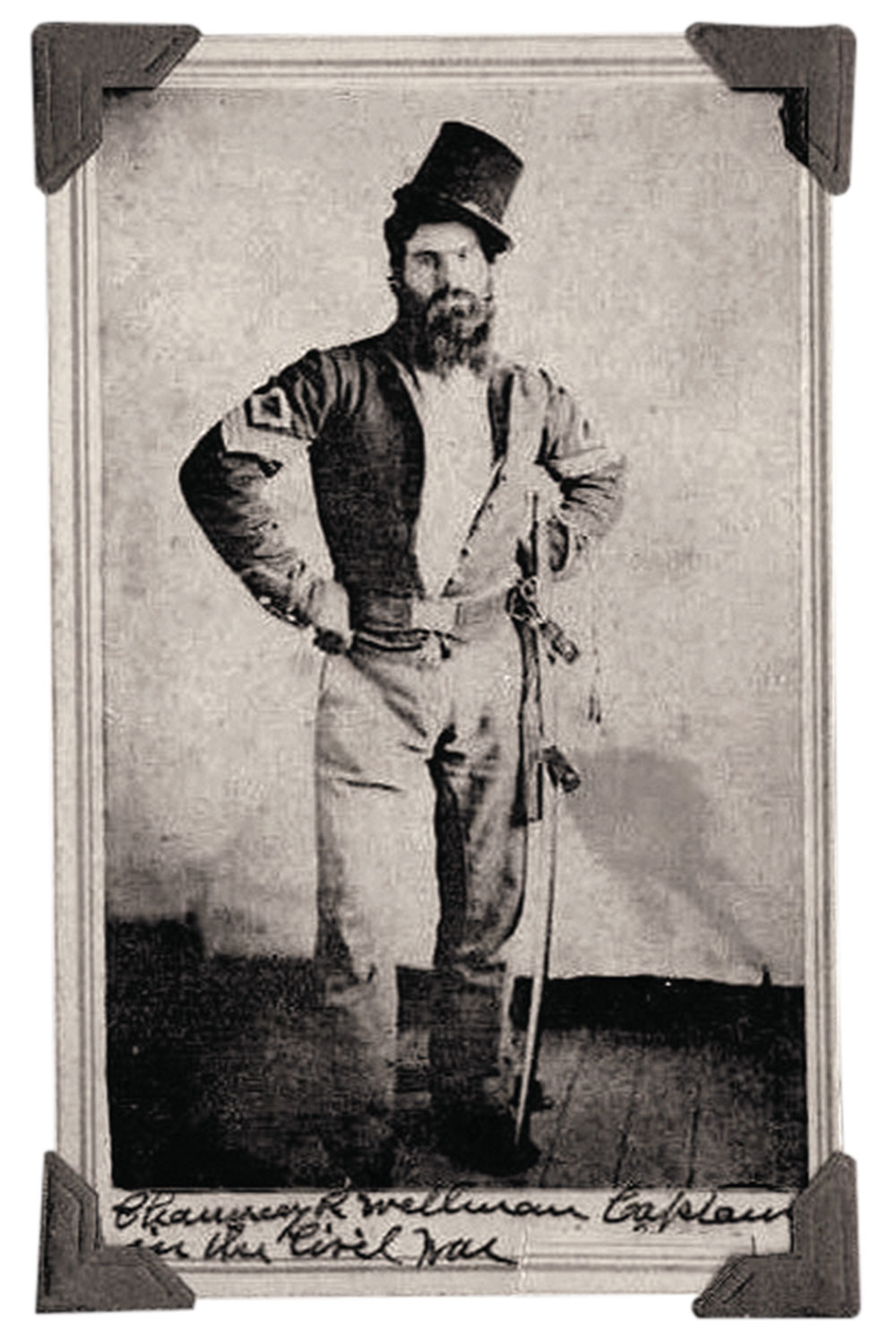

— General Richard Ewell, C.S.A., ca.1860, Courtesy Library of Congress —

The Death of Captain Stanton

On January 18, 1855, Capt. Henry W. Stanton (Co. B, 1st Dragoons) was ambushed and killed by Mescalero warriors. Also killed in the battle were Pvts. Thomas Dwyer and John Hennings. It was a cold, miserable duty for both Apache warriors and the troops pursuing them. Ewell’s report gives numbers of men and supplies. The amount of territory they covered on horseback is amazing. It is doubtful if most could cover it today, even with jeeps, in such a quick and efficient fashion with minimal supplies. Worn out horses were also a continual problem and it seemed that the Mescaleros had an unending supply, mostly stolen from local ranches and farms.

Los Lunas, N. M. (1) Maj. W. A. Nichols, U. S. Army Feb 10 1855 A.A.G. Dept. of N. M.

Sir: I have the honor to report my return from the scout ordered from your office December 21. …on the 13th of January, as previously arranged by Gen. John Garland, I met Capt. Henry W. Stanton, 1st Dragoons, Lieuts. Junius Daniel and Henry W. Walker, 3rd Infantry, and 50 Infantrymen and 29 Dragoons.

After combining the two commands I moved south toward the Guadalupe and Sacramento Mountains and then on January 17th, 1855, encamped on the Peñasco, a fine stream running from these chains toward the Pecos… This night the camp was attacked by the Indians with arrows and firearms and at the same time they tried to burn us out.

Next morning the Indians seemed in force with every mark of defiance and during the whole day opposed our march, disputing every ravine at times under cover within arrow shot. A body of skirmishers, first of Infantry, under charge, at different times, of Lieutenant Daniels and Walker, and then of mounted and dismounted dragoons, under Lieutenant Moore, was engaged the whole day in clearing the line of march. The country was broken into high hills, with deep ravines crossing the line of march. Lieut. Moore, with some of the best horses, gave chase to some Indians on the open ground but a winter march of 450 miles had reduced the horses too much to catch the Indians on their fresh animals. The Indians gave the impression from their boldness that they were trying to keep us from their families…

During this time about 15 Apaches were shot from their horses yet they continued to harass the troops. Another problem was that Ewell’s guides had never been into this part of New Mexico Territory and it was a slow slog. On the afternoon of January 18, his command halted for the day and he ordered Captain Stanton and his men to examine a small valley where a ranchería had been sighted. He charged up a hillside and…according to Ewell, “in the ardor of the chase, became separated from some of his men, badly mounted, who were unable to join him when he sounded the rally. After rallying about a dozen men he proceeded up the valley until he became satisfied that the Indians had not retreated in that direction, then he started back, leading his horses. About three-fourths of a mile from the camp the valley narrowed with trees, and here he was ambushed and fired into, the first fire killing one of his men. He ordered his party to take to the trees, but the Indians being in too great force, he mounted and ordered his party to retreat, remaining in the rear himself, firing his Sharps carbine, when he received a shot in the head and was instantly killed…”

One can just imagine the morale of the men as they quickly and temporarily buried the three bodies of brave men who had been their comrades in arms. They continued tracking Mescaleros for two more days in the mind-numbing cold. Harsh winds blew relentlessly up the ravines and into hidden canyons where Mescaleros might be lying in ambush. During this time they lost about 10 horses per day, which also added to the misery of everyone. Ewell concludes:

I had the hearty cooperation of Officers and men. Enclosed is a map of my route, drawn by Lieutenant Moore. The signal smokes of the Indians, on my return, satisfied me that they retreated towards the lower range of the Guadalupe Mountains.

–I remain, R. S. Ewell, Captain, 1st Dragoons

— Courtesy Lynda A. Sánchez Collection —

The Long Journey Home

Alas, this was not the only indignity suffered by Stanton and his men. They had been temporarily buried with intentions of retrieval of the bodies at a later time after the scout for Apaches was completed. Private James Bennett wrote about their return:

“Came to where we buried Captain Stanton and the two men. Found the bodies torn from the grave, their blankets stolen; bodies half eaten by wolves; their eyes picked out by ravens; their bones picked by ravens and turkey buzzards. Revolting sight. We built a large pile of pinewood, put on bodies; burned the flesh. Took the bones away.”

Bennett implies that the blankets were stolen, but by whom? It is well known that Apaches feared the dead and the spirits (chindi) that would haunt such a burial. Would their desire for blankets overcome their fear of the dead? It is doubtful. They probably had no idea the men were wrapped in blankets as the grave was covered with dirt and rock. Hungry wolves and coyotes were probably the culprits who had created such havoc in their quest for food.

It was, indeed, a sad and weary group that rode toward Fort Fillmore where Captain Stanton had been stationed. Also it was noted by Private Bennett that a hopeful Mrs. Stanton awaited the troops. “Poor woman. She asks for her husband. The answer is evaded. An hour passes. Her smiles are fled…tears stain her cheek.”

On the edge of the frontier such happenings were multiple and no doubt many historians gloss over the gruesome details. Bennett’s descriptions of such horrendous death and destruction is rare for the era. This was no Hollywood scenario.

— Courtesy Larry Pope, Ranger, Fort Stanton Historic Site —

Epilogue

Even in death, Stanton’s remains never found rest until years later. They were taken first to Fort Fillmore on February 3, 1856. He and his men were buried with military honors. In about 1866 he was removed to Fort Selden near present-day Radium Springs, New Mexico, and later when that fort was closed, all military burials were transferred to the Santa Fe Veterans’ Cemetery. Stanton was eventually buried at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. However, the simple gravestone does not reveal the hell he went through or the tortured manner in which his men brought him home. It had been a long journey indeed.

Author Lynda A. Sánchez was actively involved in the battle to preserve and save Fort Stanton from over commercialization. The fort is now a New Mexico Historic Site. She is a member of the Western Writers of America and is currently working on a book about the fort.