— Courtesy Kevin Mulkins —

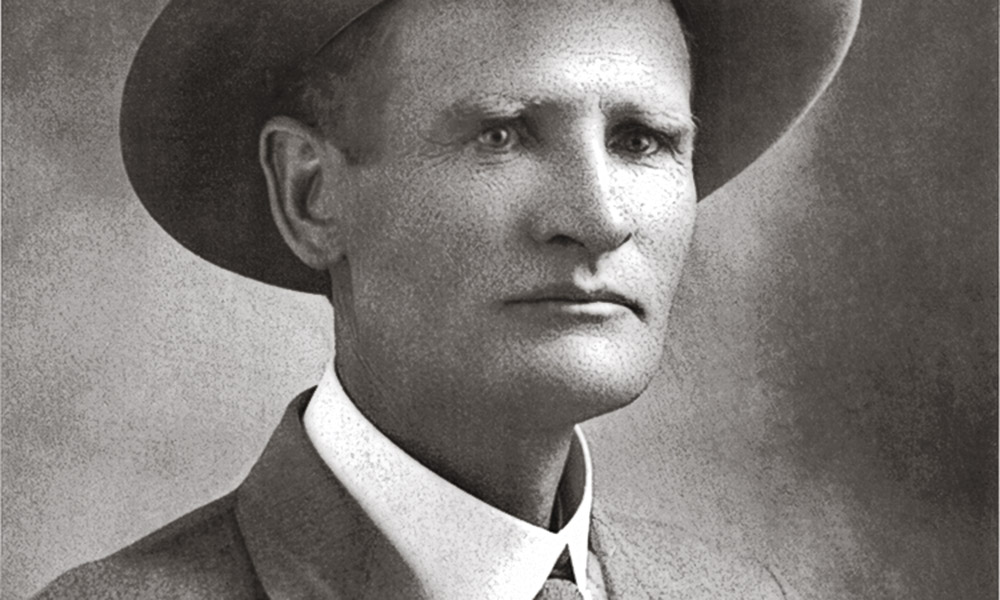

Jeff Power, like his ancestors, had clawed out a living in unforgiving terrain, continually forced to defend what little he had from predators, both human and non-human.

He inherited his distaste for war from his family’s experiences during the Civil War, while his years of combating aggression in Texas and New Mexico Territory instilled in him a populist bent, sentiments he would pass on to his three sons.

Life in Rattlesnake Canyon brought him a reprieve from the clamor of the outside world, until the draft of WWI threatened his ability to develop his gold mine, leaving him with the prospect of losing everything he had: his sons and his ability to earn a living.

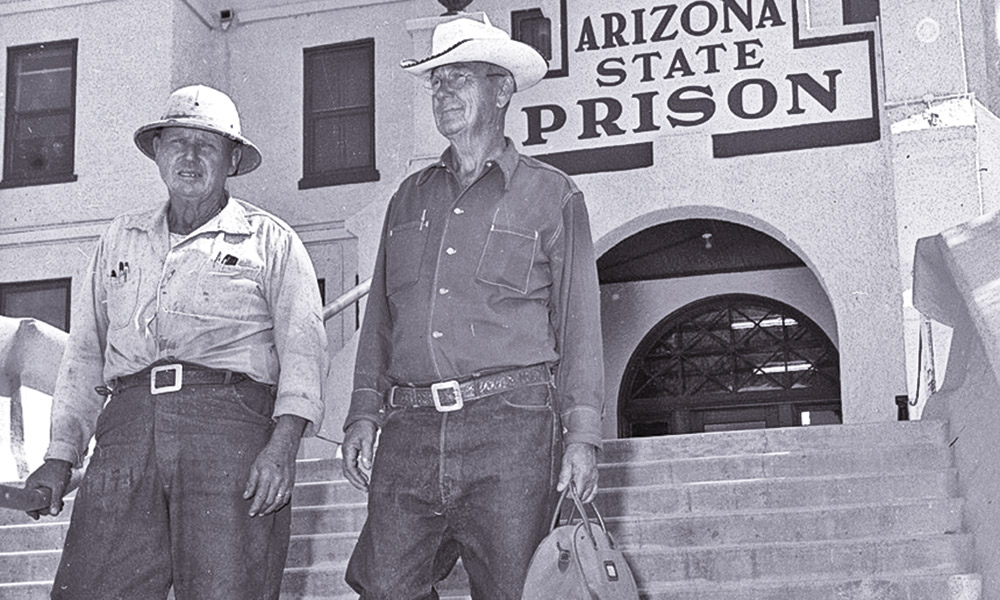

— Courtesy The Arizona Republic —

He was wary of government and eschewed society, an outcast even among the numerous outcasts living in the canyon, but the Great War required the assistance of every able-bodied person and would not allow his family to remain in isolation.

“As Americans we like to mythologize about the rugged individualist, but the truth of the matter is the rugged individualist is celebrated only in certain times for certain reasons,” historian Eduardo Obregón Pagán said about Jeff Power. “As a nation when we need to band together, we need to band together, and that individualist will pay the cost for who they are.”

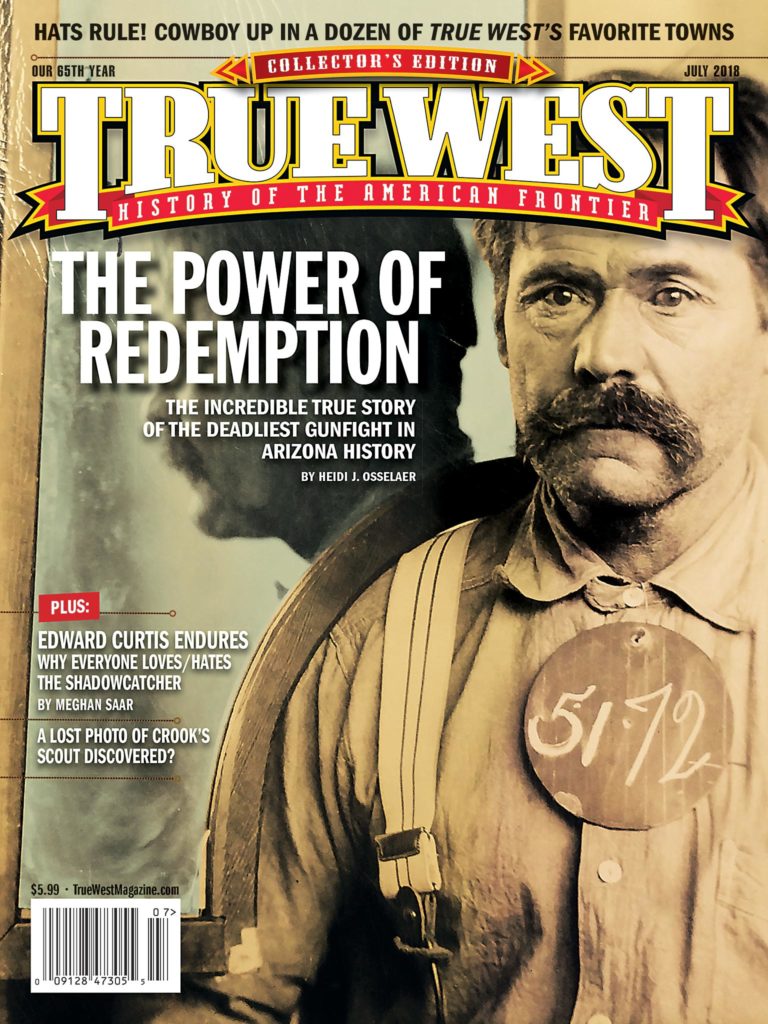

The Power shoot-out should have been forgotten long ago, an obscure side story to WWI history. Instead, the story was kept alive precisely because enough people believed the outcome was unjust.

In the end, only the death of Tom Sisson and the advanced ages of the Power brothers brought the story to light outside of Graham County and the state prison system. Even then, the path to John and Tom Power’s release was paved with distortions that transformed a straightforward case of draft evasion into a tale of feud and conspiracies.

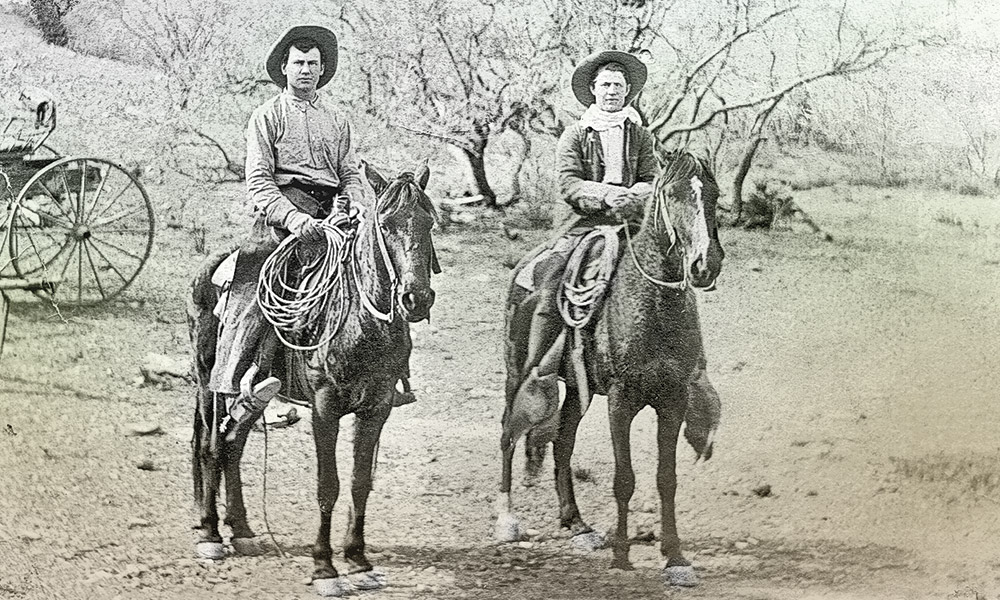

— Courtesy McBride Family —

Investigating Injustice

In the fall of 1958, Don Dedera, who wrote the most popular editorial column for The Arizona Republic, the state’s largest circulation newspaper, was at the state prison to write about one of the inmates.

Warden Frank Eyman suggested Dedera also talk to the Power boys to hear their interesting story. As a former Marine and police beat reporter, Dedera was guarded with convicted felons, who he knew often claimed to be wrongfully incarcerated.

Dedera had tremendous respect for Eyman, so he listened patiently to John and Tom Power as they told their “well-rehearsed” story of injustice at the hands of Graham County officers.

John, “slumped over like a turtle,” barely said a word the entire interview, but Tom was well-spoken and impressed the reporter with his knowledge of the law.

Their first meeting struck the columnist. The brothers had spent four decades in prison, yet, in all that time, had been granted only one formal parole hearing. Leadership in the prison considered the brothers exemplary prisoners; the same held true for Sisson, who had died the previous year, yet was never considered fit for release.

Dedera wondered why John and Tom were still incarcerated when so many others who committed similar crimes had been paroled. He decided to investigate.

Dedera soon discovered the Power brothers were their own worst enemies. They unrealistically demanded complete exoneration because they refused to shoulder any blame for the shoot-out. Had they been less stubborn, “they would not now be in prison,” said attorneys whom they had fired over the years.

The brothers gave Dedera a paper bag filled with $100 bills, explaining to him that each time they hired an attorney, they had to pay him a retainer. Dedera laughed and told them to keep their money. He did not intend to retry the case in court, but rather hoped to present both sides of the story in his newspaper columns, allowing society the opportunity to weigh in.

— Courtesy McBride Family Courtesy Millie Wootan Barnes —

Dedera’s first column about the shoot-out appeared on November 10, 1958, and primed his readers for much incendiary material to follow: “America was at war with the Central Powers. T.J. Power was at war with the people around him.”

Dedera’s Jeff Power was a domineering and “obstinately independent” man who refused to allow his boys to serve in the war. “The Power boys wanted to join up,” reported Dedera, but their father’s reply was, “I’ll see you in hell first!”

His sons were not to blame for their predicament, the columnist argued; they were victims of circumstance.

Dedera offered the Power brothers’ version of the shoot-out in his second column: “They say they were asleep when the officers surrounded their cabin…. They woke when a belled mare ran past the front of the cabin. [Jeff Power], thinking a mountain lion was after the mare, stepped outside dressed in long johns and carrying his rifle. When Kane Wootan shouted, ‘Throw up your hands!’ he complied, responding, ‘Don’t shoot.’”

Within the next six days, four more columns appeared. Dedera expressed his doubts about some of the claims made by the Power brothers, especially their suggestion that “they were railroaded by a stacked jury, unfair judge, perjured testimony and inept counsel,” noting that “much of society had judged them guilty before the trial began. But the Power boys were given their rights.”

— Courtesy Ryder Ridgway Collection, Held by Maxine Bean —

The Feud

Dedera learned a feud existed between the Powers and the Wootans. Although he was unsure what had caused the “bad blood” between the two families—people he interviewed in Aravaipa suggested Deputy Kane Wootan either had been spurned by Tom and John’s sister Ola or had sparred with the Power brothers over grazing rights—Dedera agreed with Tucson journalist J.F. Weadock’s conclusion that father Jeff, “in his stubborn attitude toward the draft, coupled with Kane Wootan’s desire for vengeance…juggled the two boys into a mess which was not of their making.”

A primary source of the feud narrative was Lee Solomon. Everyone acknowledged that the Power family was not welcomed in Aravaipa; residents were suspicious of outsiders who threatened already scarce resources. Kane became the designated ringleader, allegedly exchanging harsh words with Jeff and chasing off his cattle.

Although the Solomons were related by blood and marriage to the Wootans, the family was apparently closer to the Powers than the Wootans. When Sam and Jane Power lived in Gillespie County, Texas, from the 1860s to 1890, Lee Solomon’s parents, David Lee and Jane “Dee” Wootan Solomon, were their friends. After both families moved to Arizona, Lee Solomon punched cattle with Charley, John and Tom Power, as well as relative Kane Wootan, in Aravaipa.

Lee’s sister Delila married Kane’s father, Black Bill, in 1909 after his divorce from his first wife, Sarah, so she was Kane’s stepmother at the time of the shoot-out. Years later, her marriage also ended in divorce, adding to the existing acrimony between the Solomons and the Wootans.

— Courtesy Martin Kempton —

Dedera received corroboration of the feud from Glenn Kempton, Deputy Martin Kempton’s son, who admitted it was “common knowledge that Kane Wootan had had disputes with the Power family, that the Wootan family had conflicting claims with the Powers and that Kane Wootan and John Power had long carried on a personal vendetta.”

Although both the Power brothers and the Wootans acknowledged they had disagreements prior to the shoot-out, Tom stated, “I would not have thought that our brushes with the Wootans were cause enough for them to try to kill us.”

Tom and John Power believed the scourge had been Graham County Sheriff Frank McBride, who wanted their gold mine, tapping into long-held prejudices that Mormons stole and murdered, and then conspired to cover up their crimes. But their accusations that the sheriff was willing to kill for their mine fell on deaf ears.

After conferring with visitors to the prison during the 1950s, supporters who knew the brothers would have to find someone else to blame in order to win over public opinion, Tom and John began to entertain the possibility that the Wootan feud had precipitated the shoot-out.

Yet public records do not support a feud. Neither side had filed civil suits or injunctions over water or land rights in Graham County. Neither Kane nor any other Wootan owned property near the Power Mine, Gold Mountain or Power Garden Place, and Kane had moved to Safford a year prior to the shoot-out, far from Rattlesnake Canyon.

The most convincing evidence that the feud was not real can be found in the Bureau of Investigation reports and U.S. marshal records for the Power case. Correspondence between Sheriff McBride and federal officials, from June 1917 to January 1918, confirmed Kane Wootan played no role in orchestrating the arrest of the Power brothers. Rather, Sheriff McBride was the one determined to bring to justice every slacker in his jurisdiction.

The sheriff’s son, Darvil McBride, denied the Wootan feud was to blame, saying, “Such a story has been kicked around quite a bit since the affair, but has been proved to be only imagination…manufactured by those who must always weave intrigue and romance into any controversial and ‘old west’ affair.”

— Courtesy Arizona Daily Star —

Public Anger

Yet the Wootan feud narrative captured the public’s imagination. The men whom the press had once portrayed as the “monsters of 1918” were suddenly transformed by Dedera into “kindly old men” who had paid sufficiently for whatever role they played in the shoot-out.

Day after day, angry letters arrived addressed to the editor-in-chief and publisher of The Arizona Republic. To the lawmen’s relatives who wrote to him, outraged over public support for the Powers, Dedera acknowledged, “Personally, I am not convinced that the Power brothers should be released. That is a decision for society.”

The case could not be retried because so many documents had vanished and witnesses had died, but, as Dedera went on to say, “society, I believe, is on trial. Our way of justice has an issue before it.”

These men had been in prison longer than anyone else in Arizona history, Dedera wrote, for a crime that “from the outset was fraught with controversy and confusion and contradiction. Others convicted of similar crimes had been released, why not them?”

Attorney General Wade Church agreed to investigate the case. He made the startling discovery that someone pretending to be employed by his office had tried to defraud the Power brothers. A “Mr. Smith” told the brothers to pay $1,000 for the attorney general’s office to reopen their case. Staffers tracked down the culprit and forced him to return the brothers’ payment, but the incident piqued Church’s interest.

Church was a Harvard Law School graduate and a Democrat who had clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who, before becoming a justice on the highest court, had investigated the Bisbee Deportation in Arizona. Church undoubtedly recalled the state’s explosive conditions during WWI, allowing him to understand how a miscarriage of justice might have been carried out in the Power case. The attorney general told Dedera he was sympathetic to freeing the Powers.

In March 1960, the parole board announced it would hold a public hearing the following month for the Power brothers. Dedera expressed his opinion that the brothers had little chance for success in their bid for freedom because, “Hate is strong. Mercy is weak.”

— Courtesy Howard Morgan —

Help the Power Boys

Based on the stories he had heard about “clannish” Mormons in Gila Valley who colluded to hide any evidence that would convict one of their own, Dedera hinted of a Mormon conspiracy.

Tapping into more than a century of suspicion between the Gentiles and Saints of Graham County, established during anti-polygamy campaigns and the federal investigation into the Wham payroll robbery, Dedera suggested, “So intense has been the hatred of the [Gila Valley] group, there is a fear, unjustly founded as it may be, that the wrath of a church group will fall upon any politician who dares to help the Power boys.”

To lay the conspiracy rumor to rest, Dedera proclaimed: “Anybody who says the Mormon Church holds the Power boys’ prison key is a liar.”

Sensing the brothers might be released, McBride and Kempton’s children expressed fears that Tom and John Power might harm them or their elderly mothers. They asked the governor’s assurance that, if the brothers’ sentences were commuted, Tom and John would remain on parole, so their every move would be monitored.

— Courtesy Howard Morgan —

On April 20, 1960, Lorenzo Wright, who had served as prison warden during the 1930s and was a former stake president for the LDS church in Maricopa County, addressed the Latter-day Saint families in attendance: “I’m related to both of these wonderful families, the Kemptons and the McBrides…. God has said, if you will not forgive, he will not forgive you…. The killings were a horrible thing. If they paroled today, it will hold no jurisdiction over what God has for them. This board won’t satisfy him. They will have to face their God.”

Wilford Rene Richardson, the attorney retained by the Wootans and McBrides, told the board: “If it were made clear that these prisoners think they made a tragic mistake, the situation might be different. But they believe they were not wrong, that they were right.”

Wright confronted the prisoners: “Are you men enough? I have come here to speak in your behalf. If you are not men enough to ask forgiveness and to forgive, then I withdraw my support.”

When Tom and John failed to respond, he repeated, “Are you men enough?”

Tom, in a shaking voice, mumbled a barely audible, “We are.”

Wright demanded he repeat his answer. Tom did in a more convincing tone, adding, “We hold no hatred for anybody. We are not much acquainted with the [lawmen’s] families. We hold no bitterness. We will forgive and would like to be forgiven. What happened 42 years ago is out of our control now. We are sorry about all that happened, but there is nothing we can do about that. I thank all of you.”

The audience erupted with applause, stomping of feet and wild cheering. Bob Thomas, whose story went out on the news wires, called it “one of the most spine-tingling experiences I’ve ever covered as a reporter.”

Then came John’s turn. He had doggedly insisted on the brothers’ innocence for more than four decades, firing countless attorneys who recommended settling for anything less than complete exoneration. The words he chose at that moment were characteristically concise: “I hold no hatred for anybody. I beg for forgiveness.”

Dedera was flabbergasted, later telling his readers, “Those who knew him would more expect the San Francisco Peaks to topple into Lake Mary than to hear John Power, in a voice loud and free, beg forgiveness of the people he had considered his tormentors for 42 years.”

The next day, Republican Gov. Paul Fannin signed the papers for their release. A few days later, John and Tom walked out of the gates of Arizona State Prison and greeted their liberator, Dedera.

They presented Dedera with spurs they had made in prison. Tom told him, “We knowed you wuz a dude, so we made ’em so’s you could wear ’em in parades.”

Dedera was no real cowboy, but he had ridden to their rescue nonetheless.

— Courtesy Ryder Ridgway Collection, Held by Maxine Bean —

Plea for Pardon

Mustered out of prison on April 27, 1960, John and Tom had savings from the sale of items they made in prison—about $3,000—and the roughly $10,000 military pension Tom Sisson had bequeathed John, but additional income would be hard to find. The terms of their commutation prohibited them from receiving pay for participating in television, magazine or newspaper interviews or for publishing their story. They found work as seasonal cowpokes.

In 1963, the brothers won a partial victory from their parole restrictions, allowing them to return to Klondyke to reopen the mine. During the 1950s, the lawmen’s widows and partners had abandoned the Power mine in Kielberg Canyon. Brother Charley Power took back some claims, which he now deeded to John.

However, Tom and John had neither the physical strength nor the financial resources to reopen the claims. Even if they had, the mine probably would not have produced for them. Between 1915 and 1922, only 53 ounces of gold were found in the Rattlesnake Mining District.

Still unsatisfied with the conditions of their release, they continued to petition for a full pardon. During the Powers’ years in prison, as the country fought two world wars and the Cold War, folks had little sympathy for the aging slackers, but Vietnam changed all that. Letters supporting a pardon arrived until January 1969, when the parole board agreed to hear the plea.

The board unanimously approved the pardon, signed by Republican Gov. Jack Williams on January 25. Williams later stated, “The dramatic gun battle in Keilberg [sic] Canyon…was a story from which myths were woven…. Who will ever know the rights and wrongs of it?”

After the pardon, the two refused to admit guilt. John was emphatic: “They was out to kill us, they weren’t trying to arrest us. Hell, we didn’t even know they wanted us. They just started shooting, shot down our daddy in the doorway. You’d fight back too, wouldn’t you, if they shot down your Pa?”

Now pardoned, the brothers could profit from their story. Tom allowed John Whitlatch to write down Tom and John’s story in Shoot-Out at Dawn.

The book made many outlandish claims and demonized anyone who ever had a hand in the Power brothers’ arrest or conviction, perpetuating the far-fetched notion that greedy lawmen had plotted to kill the Power family for their mine and ignoring the fact that the brothers had evaded the draft. Despite the book’s failings, it remains the popular version of the shoot-out because it captures the sense of injustice the brothers felt about their conviction and lengthy incarceration.

Who shot first on February 10, 1918? The only men who were in a position to know—Jeff Power, Frank McBride, Martin Kempton and Kane Wootan—all died that day.

This is an edited excerpt from Arizona’s Deadliest Gunfight, by Heidi J. Osselaer, published by University of Oklahoma Press, May 2018. All images and maps appeared in the book, with the exception of the photos provided by Kevin Mulkins, Bob Boze Bell Arizona Daily Star and The Arizona Republic.

https://truewestmagazine.com/babbitt-brothers-co-bar-ranch/