— All photos Courtesy Library of Congress unless otherwise noted —

Everyone loves the Edward Curtis Indians,” Sioux scholar Vine Deloria Jr. famously declared in the introduction for Christopher M. Lyman’s The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions.

But Deloria Jr. also cautioned that Curtis’s images should be viewed as photographic art. “…if they come to represent an Indian that never was,” he continued, “and color our appraisal of things Indian with romantic shibboleths that shield us from present-day realities, then our use of them is a delusion and a perversion of both Indians and the artful expressions of Curtis.”

Since the beginning, controversy has colored what The New York Herald dubbed, in 1907, as the “most gigantic undertaking in the making of books since the King James edition of the Bible.” That enterprise began in 1906, when financier J.P. Morgan paid $75,000 for a book series on American Indians. What may surprise many is that Curtis did not earn a salary; that money was earmarked to support fieldwork for the books.

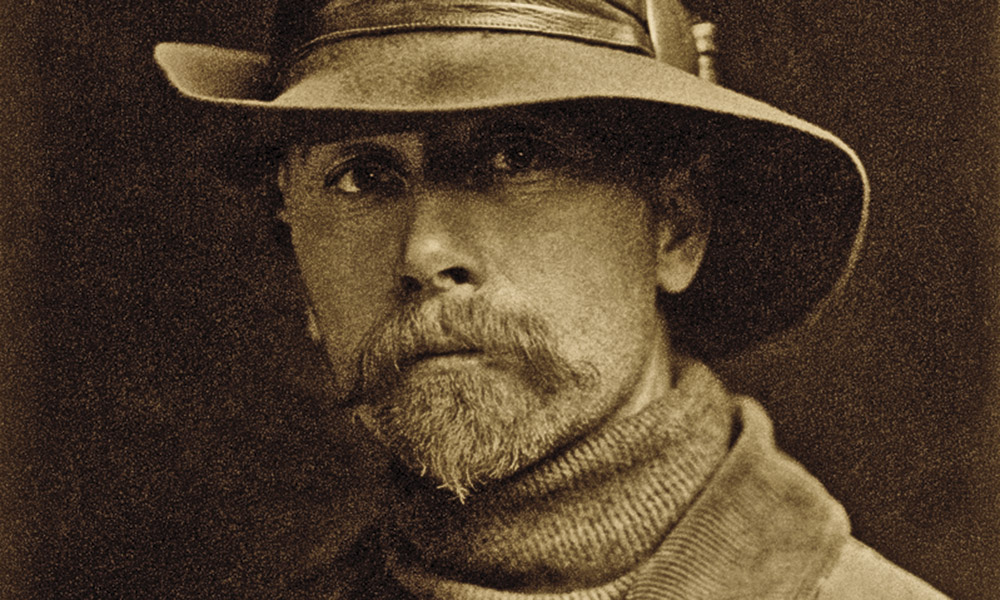

Curtis, born 150 years ago this past February, lucked into what would become his most important work. While taking pictures of Washington’s Mount Rainier in 1898, Curtis came across a group of lost scientists. One was George Bird Grinnell, who studied Indians. The two developed a friendship, particularly in 1899, when Curtis was working as an official photographer for the Harriman Alaska Expedition. The following year, Grinnell gave Curtis the keys to a new world: photographing the Blackfoot Confederacy in Montana. The prestige Curtis earned for those images had attracted Morgan’s attention.

Curtis’s first portrait of an American Indian was actually taken years earlier, in 1895, when he photographed Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle, in Seattle, Washington. Three years later, the National Photographic Society was the first to recognize his painterly style, awarding him a gold medal for “Homeward,” a sunset scene of Indians paddling to the Puget Sound shore in a canoe.

At the turn of the 20th century, over roughly 20 years, 40,000 photographs of more than 80 tribes and 10,000 wax cylinder recordings, Curtis documented tribal lore, history, food, housing, ceremonies, garments and customs. In most cases, his work is the only written recorded history, although a vast oral history also preserves the rich lifestyles of these tribes.

Dressed up in a mythic sepia gauze, his photographs of various tribes across the West, in their original environments and traditional clothing, offer a romanticized and re-created lost way of life. Yet Curtis grew up in his own project; he may have started with the idea of a “noble savage” and a “vanishing race,” removing any personal identities from his earliest photos, but over time, he built friendships and expanded his cultural understanding so that his subjects ended up with names and wearing contemporary clothing they usually wore. They became a people who were surviving, not dying off.

To be fair, when Curtis began focusing on our nation’s Indians, in 1896, total tribal population had dwindled to less than 250,000, reported biographer Timothy Egan, adding, “Many scholars thought they would disappear within a generation’s time.”

But by volume 19, the population was already increasing, having grown to nearly 350,000. Curtis did not ignore that shift. He adjusted his camera’s perspective to show the tribes as contemporaries in America, not people lost to history forever.

Even those who feel a love-hate relationship with his work cannot miss the humanity captured by Curtis’s camera, and that is why his images, more romantic than realistic, have endured. They are not anthropological specimens. They are artistic works that sometimes reveal the truths of these living souls.

So long as we do not allow Curtis’s images to pervert our understanding of the real lives led by these Indians, we should all “love the Edward Curtis Indians” preserved beyond memory by his camera and his words.

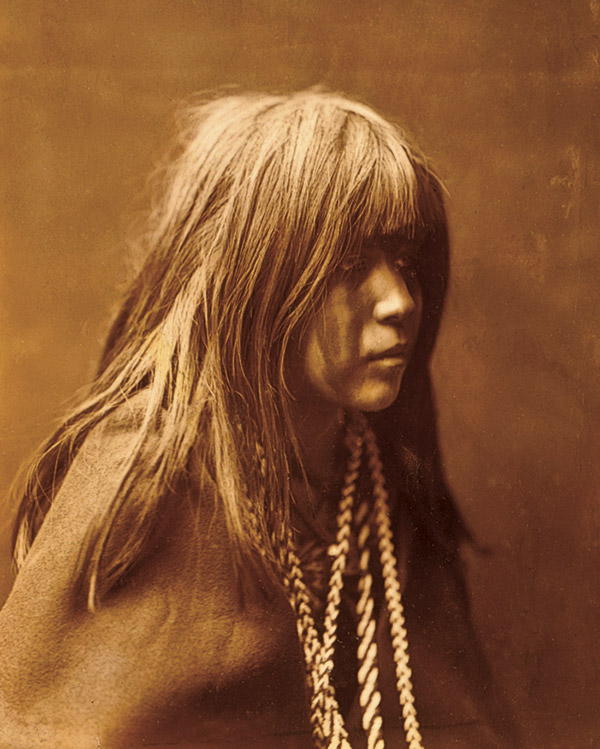

The Girl Who Sold the Project

According to Timothy Egan’s biography Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, Edward S. Curtis won over J.P. Morgan once he showed the financier his photographs of Mosa, a Mohave girl whose face was painted and who wore a series of braided necklaces over a dark blanket covering her body.

Curtis took at least two photographs of her, one showing her in profile and another one showing her facing the camera.

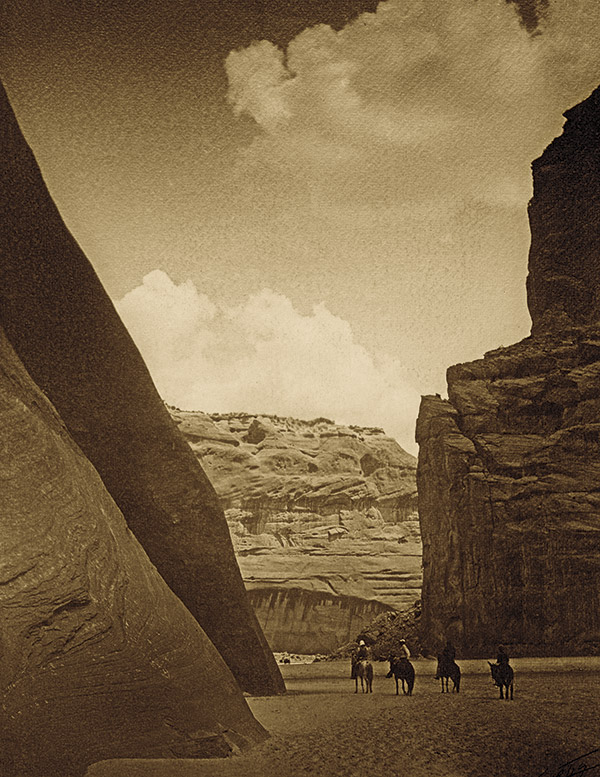

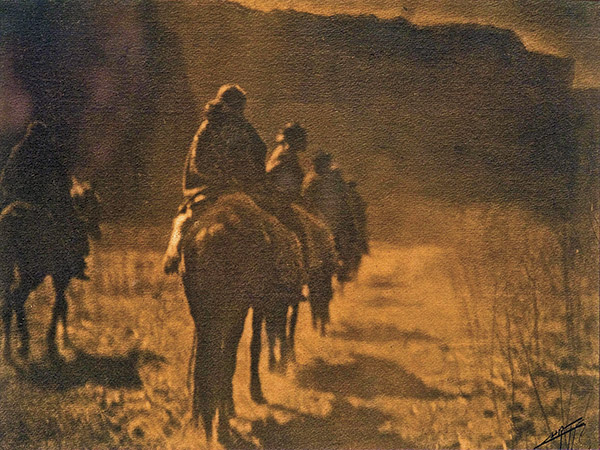

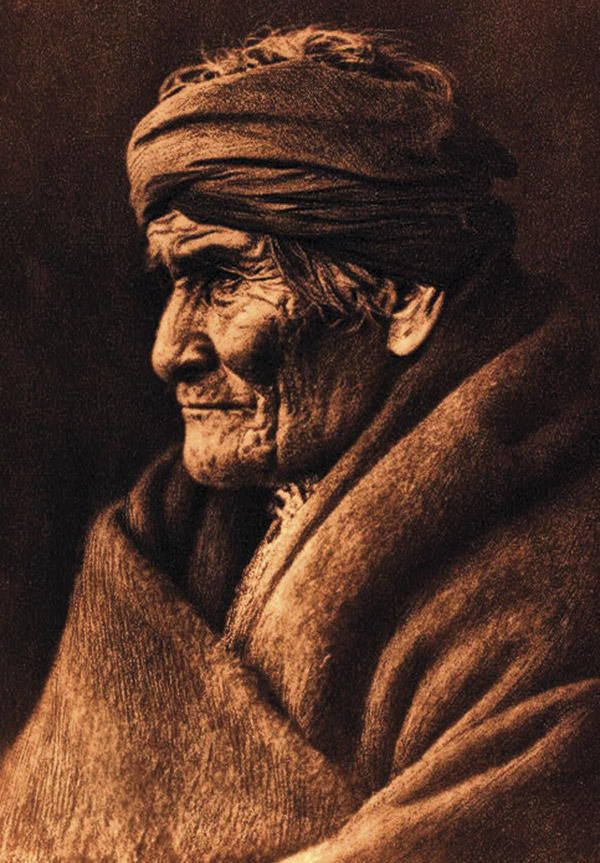

The Vanishing Race

Curtis set up the premise for his series by beginning his first portfolio of large plates with “The Vanishing Race—Navaho [sic],” followed by “Geronimo—Apache.”

Of the first photo, Curtis wrote, “The thought which this picture is meant to convey is that the Indians as a race, already shorn in their tribal strength and stripped of their primitive dress, are passing into the darkness of an unknown future. Feeling that the picture expresses so much of the thought that inspired the entire work, the author has chosen it as the first of the series.”

When Curtis photographed Geronimo, the Apache medicine man was roughly 66 years old and was waiting to appear the next day in President Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in Washington, D.C. in 1905. Curtis portrayed this venerable, famous warrior wrapped in a blanket, making him appear frail, thus further reinforcing the concept that Geronimo was among the vanquished, and that the likes of him would never be seen again.

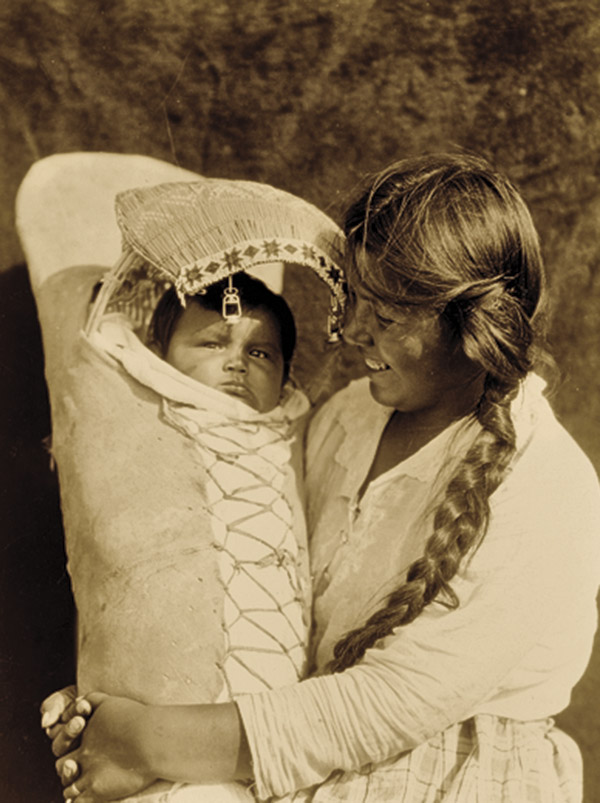

Women Through a Window

Ojibwe author Louise Erdrich showed her appreciation for Curtis’s work in her essay published in Christopher Cardoza’s Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks: “Curtis mastered the art of making his subject so dimensional, so present, so complete, that it is to me as though I am looking at the women through a window, as though they are really there in the print and in the paper, looking back at me.”

Of “A Clayoquot Maiden,” from plate nine in Volume 11), Erdrich loved how she was “hiding a laugh in her blanket of fur and cedar.” She later added “To me, Curtis’ images of women with their children are as disquieting as they are profoundly beautiful.” (See above “Achomawi mother and child,” of the Pit River tribe of California, as an example.)

At the same time, she recognized the sad truth that these children were ripped away from their mothers and sent to government boarding schools.

The Human Photoshop

For his earliest American Indian images, Edward Curtis removed modern clothes and other signs of contemporary life.

Two portraits of a Piegan Lodge, for example, originally showed an alarm clock between Little Plume and son Yellow Kidney, as seen in the negatives, preserved at Library of Congress.

In the view published in his The North American Indian series, Curtis cut out the clock.

Evolution of a Photographer

Curtis evolved as a photographer over his roughly 20 years of capturing American Indians through his camera lens for this project. He did not remove evidence of contemporary life, umbrellas, from this photo, labeled, “At the Pool, Animal Dance—Cheyenne,” from plate 663 of Volume 19, The Indians of Oklahoma.

Evoking Past Freedoms

Riding across Montana’s “primal upland prairies” and stopping at one of its “limpid streams,” these three Blackfoot Chiefs—Four Horns, Mountain Chief and Small Leggings—evoked wonder at why civilization would appeal to a people used to the freedoms of their old way of life. “A glimpse of the life and conditions which are on the verge of extinction” was part of Curtis’s label for what has become one of his best-known pictures.

Teddy’s Endorsement

In 1906, the same year Teddy Roosevelt received the Nobel Peace Prize, the president endorsed Curtis’s project. The photographer’s work included touching images of children, although not all got published in his series, including the above photo of a Hopi boy herding horses and sheep across sand dunes in New Mexico Territory.

Roosevelt wrote, “Our generation offers the last chance for doing what Mr. Curtis has done. He has lived on intimate terms with many different tribes of the mountains and the plains. He knows them as they hunt, as they travel, as they go about their various avocations on the march and in the camp. He knows their medicine men and sorcerers, their chiefs and warriors, their young men and maidens. Mr. Curtis, in publishing this book, is rendering a real and great service; a service not only to our own people, but to the world of scholarship everywhere.”

At the same time, Roosevelt was also the same man who had said, in 1886, about the people Curtis was capturing on film: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” During his presidency, his staff took steps to encourage assimilation and erase tribal ties, including the famous “haircut order,” five months into office, which argued that forcing males to wear short hair would “hasten their progress towards civilization.”

Curtis met the President in 1904, after he won a 1903 portrait contest by the Ladies Home Journal for “Prettiest Children in America.” Curtis got invited to the White House to photograph the Roosevelt children, and thus begun a lifelong friendship. Shown in the photo above is newspaperman Walter Russell with Quentin Roosevelt on his shoulders as Archie digs in sand and Nicholas lies buried in sand at Sagamore Hill.

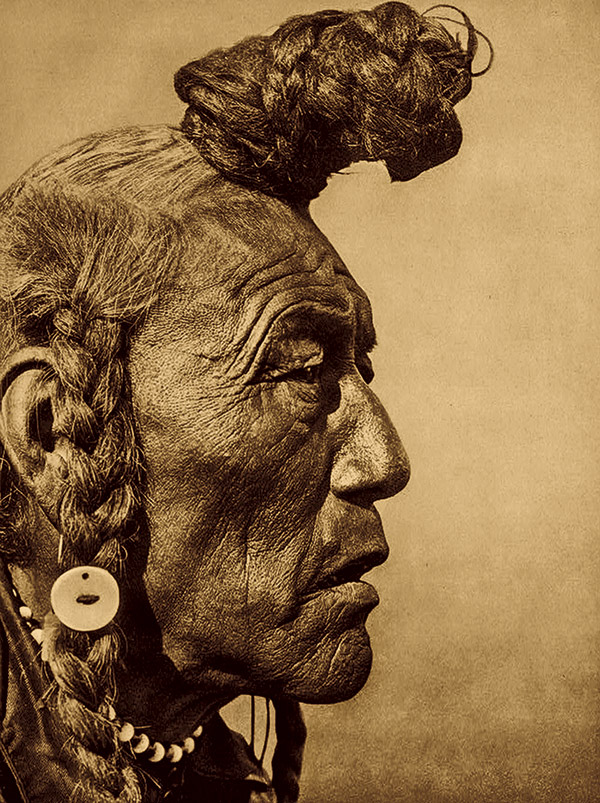

The Bald Indian

Assimilationist practices to “civilize” American Indians took place at reservations and particularly at boarding schools. Beyond attempts to erase the language and cultural traditions, even long hair was shorn. Curtis solved the problem by adding hairpieces, as he did in his photograph of Blackfoot Bear Bull (above, notice the top knot is darker than his real braids).

Sometimes Indians wanted to wear a wig, as in the case of Blackfoot Chief White Calf below). In October 1900, San Francisco’s Sunday Call reported Curtis saying:

“White Calf, though he urged the others to pose, was very coy when it came to taking the medicine himself. Finally he consented. I was anxious to get him not only because he was chief but he is one of the few baldheaded Indians I have ever heard of. He appeared as promised, but alas! instead of the picturesque everyday garb he was got up regardless in a faded misfit blue uniform, obtained heaven knows how. His bald head was covered with an elaborate blond wig, on which perched an army hat several sizes too small.”

The “Authentic” Look

Curtis attempted to preserve the traditions of North American Indians via both text and photography. But cultures evolve and change over time, which he communicated admirably in Volume 13, plate 441, “A Klamath,” shown below.

In his caption, the photographer admitted, “The entire costume here depicted is alien to the primitive Klamath. The feather head-dress and fringed shirt and leggings of deerskin were adopted by this tribe within the historical period, along with other phases of the Plains culture, which extended its influence to the Klamath country by way of Columbia river and the plains of central Oregon.”

To describe one view of a Klamath, or any other American Indian, as more “authentic” than another is to ignore that, over time, communities alter and adopt practices they’ve learned from other communities. This Klamath elder man differed in attire and weaponry from his ancestors, but he was still quintessentially a Klamath.

At the same time, Curtis was guilty of using various props in elaborately staged scenes. For example, you can see the jewelry Mosa wears elsewhere. His most glaring additions were hairpieces.

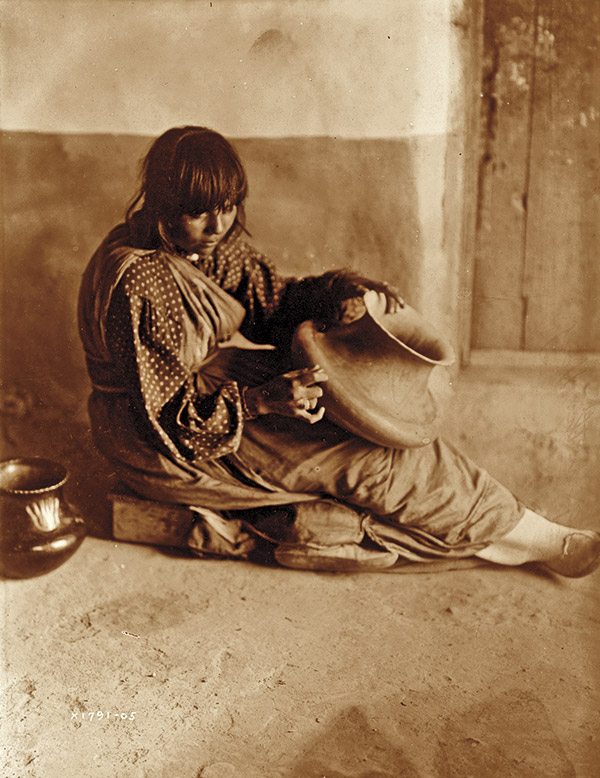

Women’s Work

Ojibwe author Louise Erdrich’s favorite Curtis images were those celebrating women’s work. “His eyes linger on the feel of thing, the baked earthen vessels, the clay under the potter’s hands as she mixes it, the motion of the reaper, the tensile beauty of a loom set against a canyon wall,” she wrote in her essay for Cardoza’s book.

These “humble arts [remain] the strength of Native culture lives,” she continued. “Women still make pots using the same techniques and designs.

Women still reap crops and harvest rice in canoes. And into their rugs and baskets, their clothing and beadwork, Women still weave the sacred symbols of their nations.”

Curtis the Filmmaker

One controversial Curtis subject was the Oraibi snake dance performed by the Hopis in Arizona Territory. Curtis captured this dance in a photograph published in Volume 12 (bottom, showing onlookers in the background), and he also documented the dance on movie film, in November 1904. Yet the Hopis had never meant for this ceremony to be recorded.

During his fieldwork for The North American Indian series, Curtis decided to film the fictionalized Kwakwaka’wakw drama In the Land of the Head Hunters, released in 1914. In the above photograph, Curtis is shown behind the camera, next to interpreter and Assistant Director George Hunt, who holds a megaphone.

The next decade, Curtis graduated to Hollywood. In 1923, he served as second cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille’s silent epic The Ten Commandments.

He continued to work with DeMille, probably also on his Tarzan films, and he ended his film career with a Western, 1936’s The Plainsman.

https://truewestmagazine.com/curtiss-big-dream/