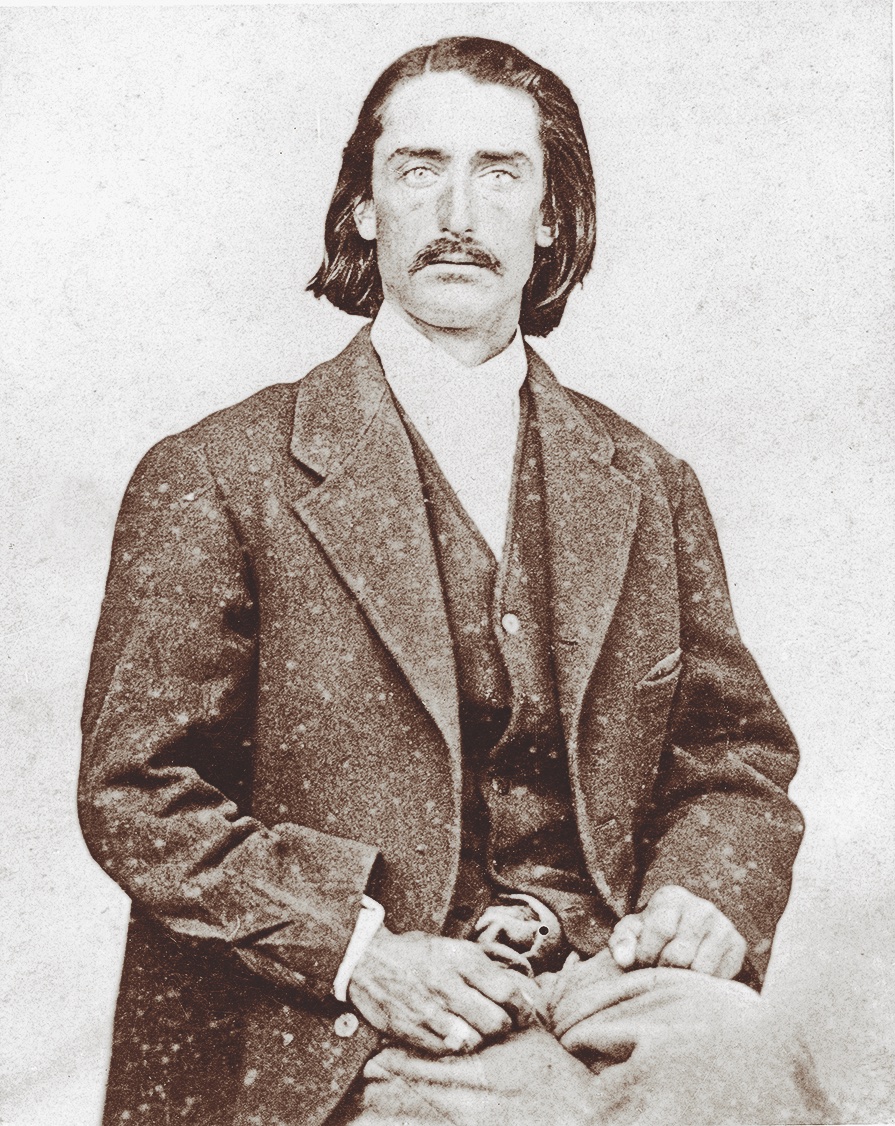

Will “Medicine Bill” Comstock was an enigma to many of his contemporaries. Some claimed he was a half-breed Cheyenne, and others that he had been stolen by the Indians as a child, but preferred to live with the whites. However, the Junction City Weekly Union of February 9, 1867, reported that he had been born near where Fort Wallace then stood and was “acquainted with all that vast region from the British Possessions south to Texas” and that he had never been farther east than Leavenworth, Kansas.

In truth, Comstock was neither a half-breed, a stolen child or Western-born. Rather, he came from genteel Eastern stock and was a grand nephew of James Fenimore Cooper whose Leatherstocking Tales of the revolutionary frontier had inspired an ongoing fascination with the West. Born on January 17, 1842, in Comstock Township, Kalamazoo, Michigan, William Averill Comstock was orphaned at an early age, and he and his sisters were brought up by relatives. By 1860, however, young Will was reported to be an Indian trader in Cottonwood Springs, Nebraska Territory, and by the middle 1860s he was well known as an Indian scout and interpreter.

General George Armstrong Custer in his book My Life on the Plains wrote that “No Indian knew the country more thoroughly than did Comstock. He was perfectly familiar with every divide, water-course, and strip of timber for hundreds of miles in either direction. He knew the dress and peculiarities of every Indian tribe, and spoke the language of many of them.” Custer found him to be very knowledgeable on all manner of subjects and to be the perfect gentleman.

Other Army officers shared Custer’s opinion, and Comstock’s services were always in demand. In fact, it was his presence with the command that prevented what could have led to the deaths of Custer, Hancock and many of the troops who accompanied them the summer of 1867 in what was recalled as “Hancock’s Indian War.” To understand why, we must go back to 1864 and the Sand Creek Massacre when Black Kettle’s Cheyenne were massacred at Sand Creek. Black Kettle had escaped as did Edmund Guerrier, the half-breed son of William Guerrier, a French trader, and Tah-tah tois-neh, a full-blooded Cheyenne, and his brother-in-law George Bent.

“No Indian knew the country more thoroughly than did Comstock . . .” —General George Armstrong Custer

Guerrier (generally called “Ed Geary”) never again trusted the whites. In later years Bent claimed that Ed did his best to lead Custer’s troops away from the Indians and warn them in advance, while at the same time he plotted revenge. But once Comstock arrived, with his personal knowledge of Indians and ability to speak their language, Ed realized that it would not be long before Will found out what he was up to and informed Custer.

Comstock was known as “Medicine Bill” among his companions primarily because of his superstitious nature. Even his “evil-looking” dog was said to have had a “medicine collar. ”The Indians, however, called him “Medicine Bill” because Bill had cut off a man’s finger in order to save him from a rattlesnake bite.

Despite his high reputation among fellow scouts and the Army, there were those who, because of his long association with Indians, regarded Comstock as a renegade. Will, however, dismissed such claims and continued placing himself at risk in the fervent hope that peace could be restored to the plains country.

Many who have compared Will Comstock with the likes of Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill and other well-known scouts and guides, have speculated that with the right kind of publicity he would have achieved similar nationwide notoriety and enduring fame. Perhaps, but apart from a few inaccurate news reports, he managed to avoid too much attention from the press. As for his so-called rivals, it is believed that he and Hickok knew each other—there is a story that they were both at Monument Station, Kansas, when a bunch of Denver thugs got out of hand and Comstock watched in awe as Hickok beat up their leader for insulting the agent’s wife.

In so far as Buffalo Bill Cody was concerned, he claimed to have beaten Comstock in a horseback buffalo-hunting contest for the title “Champion Buffalo Killer of the Plains.” According to Cody he killed 69 buffalo against Comstock’s 46. No contemporary evidence has been found, and we have only Bill’s word for it.

Early in 1868 at Fort Wallace, Comstock blighted his impeccable record when he confronted H.P. Wyatt, a wood contractor for the post. Wyatt owed him money and refused to pay. Comstock, who was already incensed by Wyatt’s claim to have been with Quantrill when he sacked Lawrence, Kansas, in 1863, is reported to have pulled his pistol and shot him (some reports say in the back) before making his escape to Hays City. M. E. Joyce, justice of the peace, is reported to have let him go for “want of evidence,” and by August, Comstock was again scouting for the army.

He and Sharp Grover, another scout, were ordered by Lt. Fred Beecher (of the Battle of Beecher’s Island fame) to go to the camp of the Cheyenne chief Turkey Leg to try and persuade him to dissuade his young men from going on the warpath. Both men had lived with the chief and hoped he would cooperate. But the meeting was tense, and though they thought they were being escorted safely from the village, both scouts were shot down and left for dead. Wounded, Grover faked death, and in darkness made his way to the railroad and was picked up. It has been reported that Will’s body was never recovered, but it is now believed that it was, and that he was buried at Fort Wallace.

As a scout, courier, interpreter, all-round brave and adventurous individual, William Averill Comstock was in a class of his own, an opinion shared by many of his contemporaries. The Omaha Daily Herald (Nebraska) of August 27, 1868, eulogized that he also “had the confidence of his officers, and many warm friends wherever known.”

Joseph G. Rosa co-edited our September 2001 Wild Bill Hickok Collector’s Edition and wrote the definitive biography, They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok.