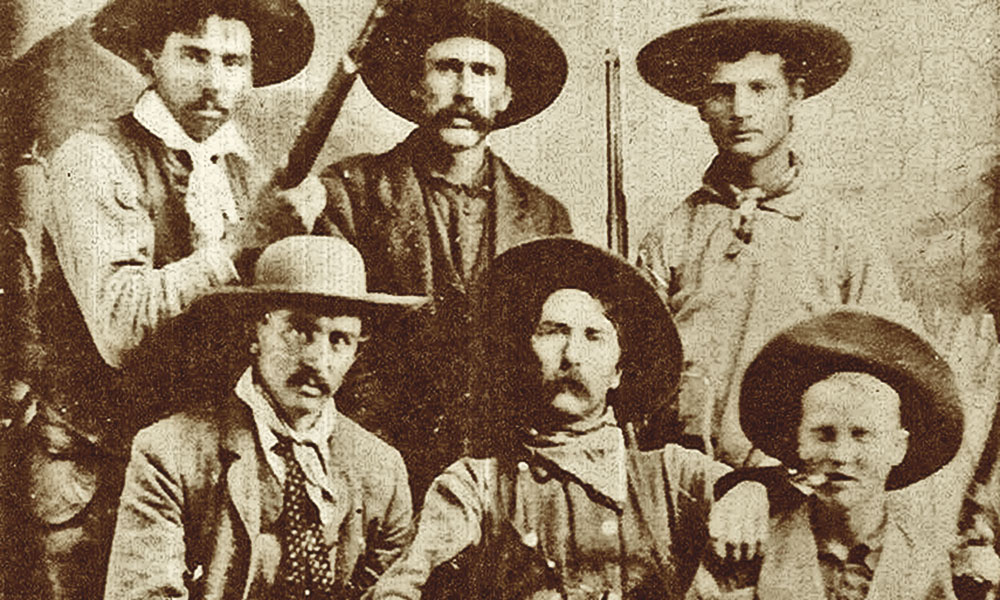

— Courtesy Jan Lundy —

A black kid with a shining smile suddenly appeared in Colorado City, Texas, in 1886, hoping to make two bits a pop as a bootblack for blacking a pair of boots.

Scripio “Zip” Means was nicknamed after his father, Zip, who had moved to Freestone County from Alabama with the family’s slave owner, Dr. J.S. Means. Once the boy reached Colorado City, though, he changed his first name to Harvey.

Harvey became the best rag popper in town. In 1886, the 18 year old was asked to move his bootblack stand to the barbershop in the St. James Hotel. One day three years later, when barber Gus Bertner was away, cowboys demanded Harvey cut their hair, so he gave in. Thus, began his 54-year career as a barber.

His notable customers included John B. Slaughter of the U Lazy S Ranch and C.C. Slaughter, sons of George Webb Slaughter, messenger during the 1836 Alamo battle; Guff Beal, a Borden County cattle king; Mitchell County Sheriff Dick Ware, one of the Texas Rangers credited with killing Sam Bass; S.B. “Burk” Burnett, 6666 Ranch owner; and Archie Johnson, the founding father of Colorado City.

— Courtesy Mitchell County Museum —

In 1912, when the St. James Hotel burned down, Winfield Scott and other cattlemen helped Harvey set up his barbershop in Fort Worth, a major cowtown about 220 miles east. Harvey led civic, religious and fraternal affairs, including the establishment of Greenway Park, a first in the city for blacks, and Fort Worth’s first black hospital. His 10 children all attended college.

When Harvey died of heart failure on May 19, 1943, one of the first to be notified was his old boss, Bertner, an insurance man in Little Rock, Arkansas. He had learned his lesson; Bertner had no fire insurance when his barber shop burned down with the St. James Hotel.

Harvey’s scissors had busied themselves on the locks of many of Texas’s most famous cowmen and businessmen, who were followed by their children and grandchildren, until, at the last, he was cutting the hair of the fifth generation.

A row of old-fashioned shaving mugs, inscribed with the names, initials or brands of their owners, provided proof of his pioneer cattlemen customers. Some of these mugs had been lost in the St. James Hotel fire, but Harvey took the remainders with him to Fort Worth. He eventually gave them to descendants of those early-day cowmen.

Harvey was like a father to many citizens of Fort Worth. Even though his name is displayed on a historical maker on a remote country road six miles west of Teague, near his birthplace, time has almost erased his story—of a man who came from a humble beginning, with little or no education, and ended up one of the most successful black men in West Texas.

Norman Wayne Brown is the coauthor of Early Settlers of the Panhandle Plains and A Lawless Breed: John Wesley Hardin, Texas Reconstruction, and Violence in the Wild West.