ENJOY THE ADVENTURE AND HISTORICAL SITES BETWEEN ST. LOUIS AND FORT LARAMIE.

When we think and write about the over- land trails, we usually start somewhere in the east at a place like St. Louis, Independence, Kansas City or St. Joseph and follow the trail west. But the trail went both directions, so this time I am starting at Fort Laramie. Never fear, we will get back to the West on this journey.

Fort Laramie, established as a military post in 1849 to provide protection for travelers along the overland trails leading to Oregon, California and the Mormon settlement in Utah, became the most valuable post in the region. In that period almost everyone traveling east or west passed through Fort Laramie, where they could find supplies, collect or deposit a letter, and learn news of the trail.

Near the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers, the post for three decades provided for overland travelers, served as a military post, and played a role in negotiations and relations with the tribes of the Northern Plains. Fort Laramie is now a national historic site.

On from Fort Laramie

The area near the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers became strategically significant in 1834 when Robert Campbell and William Sublette established Fort William as a center for fur trade. Fort William was close to the site where Fort Laramie was later constructed.

Thomas Fitzpatrick guided the first wagon train over the Oregon Trail in 1841, and he also led John C. Fremont’s first expedition into the West in 1843. The importance of Fort William had dwindled after the last big Rocky Mountain fur rendezvous in 1840, but the value of its strategic location was clearly evident, which led to Fort Laramie’s construction as a military post in 1849.

In 1812, Robert Stuart and a party of fur men from Astoria on the coast in Oregon, traveled back to St. Louis. They located a pass—which would be the funnel for people headed west later in the century—and rightly called it South Pass. They did not cross that pass, but instead broke over the

Continental Divide farther south. They reached the Sweetwater River and then the North Platte, which they followed until finally striking southeast to the Missouri River and back to St. Louis. In essence, they followed the Oregon Trail from Oregon to Missouri—west to east. Their trip would be replicated by tens of thousands half a century later with most then headed east to west.

– IMAGES COURTESY NPS.GOV

Western Nebraska

In far western Nebraska in 1828 fur trapper Hiram Scott lost his life at a sandstone outcrop that now bears his name, Scotts Bluff. A pass just south of the outcrop was the site of the Robidoux Trading Post, which was

established at the end of the fur trade era by members of the Robidoux family, prominent fur traders and residents of St. Joseph, Missouri. At Scotts Bluff National Monument you can hike the overland trail route through Mitchell Pass, where the landscape is much the same as it was when Stuart and his Astorian party came through in 1812. The nearby Legacy of the Plains Museum has exhibits on trail history.

– COURTESY NPS.GOV –

– COURTESY CANDY MOULTON –

– COURTESY NPS.GOV –

– COURTESY CANDY MOULTON –

Another key provisioning point on the trail was at Fort Kearny, established in 1849 beside the North Platte River in central Nebraska. This post, which succeeded earlier posts of the same name that were near the Missouri River in Nebraska City, is a Nebraska State Historic Site today.

The overland route, like an old rope, is frayed at its eastern end as travelers used various routes until they merged at Fort Kearny. One braid links to places in eastern Nebraska, including the Omaha area, where Mormon travelers had a major encampment before they set off toward their new home in the Great Salt Lake region. The more well-traveled trails led to jumping off places including St. Joseph and Independence, Missouri, then extended on to the gateway to the West: St. Louis.

Captain William Clark lived in St. Louis after the Corps of Discovery completed its exploration of Louisiana Territory in 1806. President Thomas Jefferson appointed Clark as the U.S. Agent of Indian Affairs. When Missouri Territory was established in 1813, Clark became the Territorial governor, under appointment first by President James Madison and later by President James Monroe.

– COURTESY NPS.GOV –

Gateway to the West

In 1822, Gen. William H. Ashley and Maj. Andrew Henry organized a fur company in St. Louis, which sent scores of trappers into the field, making the mountain men the vanguards of westward expansion beyond the Mississippi River. Among them were Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, William Sublette and Hugh Glass.

Visit the Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis to learn of the legacy of Thomas Jefferson and the American Western expan- sion, then head west!

Just west of St. Louis is St. Charles, established in 1821 as Missouri’s first state capital. The first legislature in the territory met in St. Charles. Debates on issues of states’ rights and slavery dominated the early sessions held in the House and Senate Chambers on the second floor of a new structure built by Charles and Ruluff Peck, who operated a general store in the first-floor rooms. This first state capitol served four Missouri governors until a new capitol was built and opened in Jefferson City in 1826. The St. Charles historic district has plenty to offer in buildings that date to the 18th and 19th centuries, and figure in Lewis and Clark and fur trade history.

Trails East and West from Independence

Most recognize Independence, Missouri, as the eastern terminus of the overland trails because thousands began their journeys by wagon to Oregon country from the Independence courthouse square. The National Frontier Trails Museum provides the background you’ll need to follow the trail west, and you can learn more about the trails from the Oregon- California Trails Association, also headquartered in Independence.

A number of important trail sites in the Kansas City area are identified and interpreted in a program managed jointly by local, state and federal organizations.

The best way to find them is to pick up a copy of one of the National Park Service auto tour guides to the trails. These guides also will take you to other sites on the main routes of the Oregon and California trails.

– IMAGES COURTESY PONY EXPRESS MUSEUM –

St. Joseph and the Pony Express

The Pony Express Trail, established in April 1860 and in use until October 1861, started in St. Joseph, Missouri. Headquarters was at the

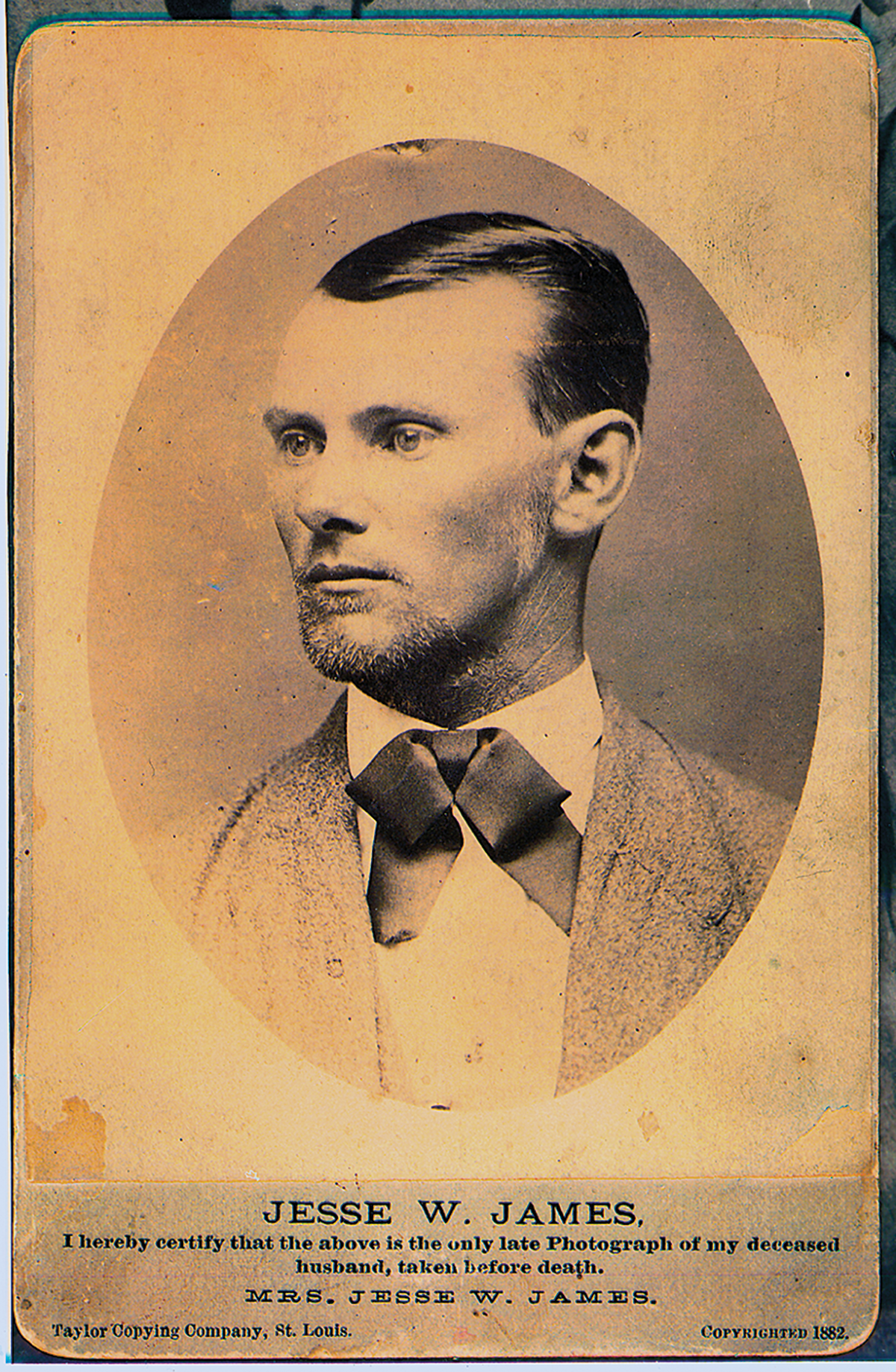

Patee House, which today is the Patee House Museum and Jesse James Home. Constructed in 1858 by John Patee, the luxury hotel served travelers and later housed the office of the provost marshal and was used as a courtroom following the Civil War. Today’s museum includes interpretation of those uses and the building’s importance to the Pony Express story. The significant hotel structure dwarfs the Jesse James

home, located behind it, but of course the James story remains larger-than-life and this is just one of the Missouri sites directly related to the famous outlaw and his family. With his wife, Zerelda, and two small children, James lived here under an alias name beginning in 1881. In this home he was shot and killed by Robert Ford.

– PHOTO OF JESSE JAMES HOME INTERIOR COURTESY PATEE HOUSE AND JESSE JAMES HOME/PHOTO OF JESSE JAMES COURTESY TRUE WEST ARCHIVES –

The original stables used by the Pony Express were in disrepair by 1950, when the structure was purchased and restoration began. The structure is now a focal point of the Pony Express National Museum. Among the original artifacts housed in the museum are saddlebags believed to have been used by express riders during its 18-month history, a variety of saddles demonstrating their evolution during the period, and dioramas that interpret the express riders and the three men who started the service, Alexander Majors, William Russell and William Waddell. The museum presents details about the Pony Express Trail, which has endured despite its short life of linking the East with the West at a critical time in our nation’s history.

Also worth visiting in St. Joseph is Robidoux Row Museum, an early apart- ment house owned by the city’s mayor, Joseph Robidoux, who was part of the extensive Robidoux clan of fur traders, trappers and business owners.

Traveling west, the best-known Pony Express Station in Kansas is Hollenberg Station, used by the express riders during their brief heyday, and still standing strong as a Kansas State Historic Site.

Distinct swales caused by wagon traffic in the 19th century are visible at Rock Creek Station near Fairbury, Nebraska. This site, built in 1857, served late-era wagon trains of pioneers headed west, and also was a stop on the Pony Express Trail. It is recognized for its connection to James B. (Wild Bill) Hickok and the shootout that killed David McCanles in July of 1861 when McCanles came to the station to collect a debt. The Nebraska State Historic site provides information about the Pony Express and the Hickok killing of McCanles, but the greatest value in stopping here is to see the trail swales.

As noted in our eastbound trip, Fort Kearny was a layover point for 19th-century travelers, and the place where most of the braided trails came together, so continuing back to the west, stop at the Gothenberg Pony Express Station, which was moved from its original location and now is operated as a museum in the town of Gothenberg, Nebraska. It is certainly one of the best- preserved Pony Express stations along the entire route.

Wagon travelers on these trails were challenged by California Hill, west of Brule, Nebraska, and found the descent of Windlass Hill daunting. They generally rested and regrouped in Ash Hollow before following the North Platte River into the area they called the Valley of Monuments. Much of the trail crossing Kansas and Nebraska is across rolling grassland, which had few land- marks. But now they could see sandstone outcroppings that were easily distinguish- able and visible for many miles—often for days before actually drawing near to them.

These landmarks soon had names: Ancient Bluff, Jail and Courthouse. Chimney Rock became a universal symbol of the trail—one of the most noted land- marks in all overland journals and diaries, second only to Independence Rock, farther west. Chimney Rock State Historic Site is not right at the rock (which is on private

property), but offers great views. There you will learn the stories of this important landmark and the trails and people who passed by it, including American Indians, fur trappers, trail pioneers and the Pony Express.

We are now full circle, back to Scotts Bluff, Mitchell Pass and Fort Laramie. You may feel as if you are coming or going on this trail adventure, so remember that while many went west, others turned back, or simply had a need to travel east to resupply for another journey or adventure in the West.

Wide Spot in the Road – Julesburg, Colorado

The Pony Express route crossed the length or width of several states: Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and had key locations in Missouri and California. The Pony riders also crossed into the extreme northeastern corner of Colorado, covering just 26 miles within the state’s boundaries. At the time the Pony Express operated, Julesburg had a station for the riders. Today you will find markers and a monument to the Pony Express. But there is much more history in Julesburg and the surrounding area along the South Platte Overland Trail.

One of the early structures in the area was Fort Sedgwick, a military post in use from 1864 to 1871 and also known as Post at Julesburg, Camp Rankin and Fort Rankin. Far more people may recognize it because as Fort Sedgwick, it was a key site in the 30-year-old film Dances with Wolves. Julesburg was raided twice and burned by Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota Indians in 1865, but the town rebounded and rebuilt.

– COURTESY NPS.GOV –

GOOD EATS AND SLEEPS

GRUB:

- Switchlist Restaurant, St. Louis, MO

- Ophelia’s Restaurant, Independence, MO

- Gates Bar-B-Q, Kansas City, MO

- Betty’s Café, St. Joseph, MO

- Rowdy’s Steakhouse, Fairbury, NE

- Cunningham’s Journal, Kearney, NE

LODGING:

- St. Louis Union Station Hotel, St. Louis, MO

- Intercontinental Hotel, Kansas City, MO

- Rowse’s 1+1 Ranch, Burwell, NE

- Fort Robinson State Park, Crawford, NE