Hit the road and discover the historic and mystic lands of New Mexico’s legendary author.

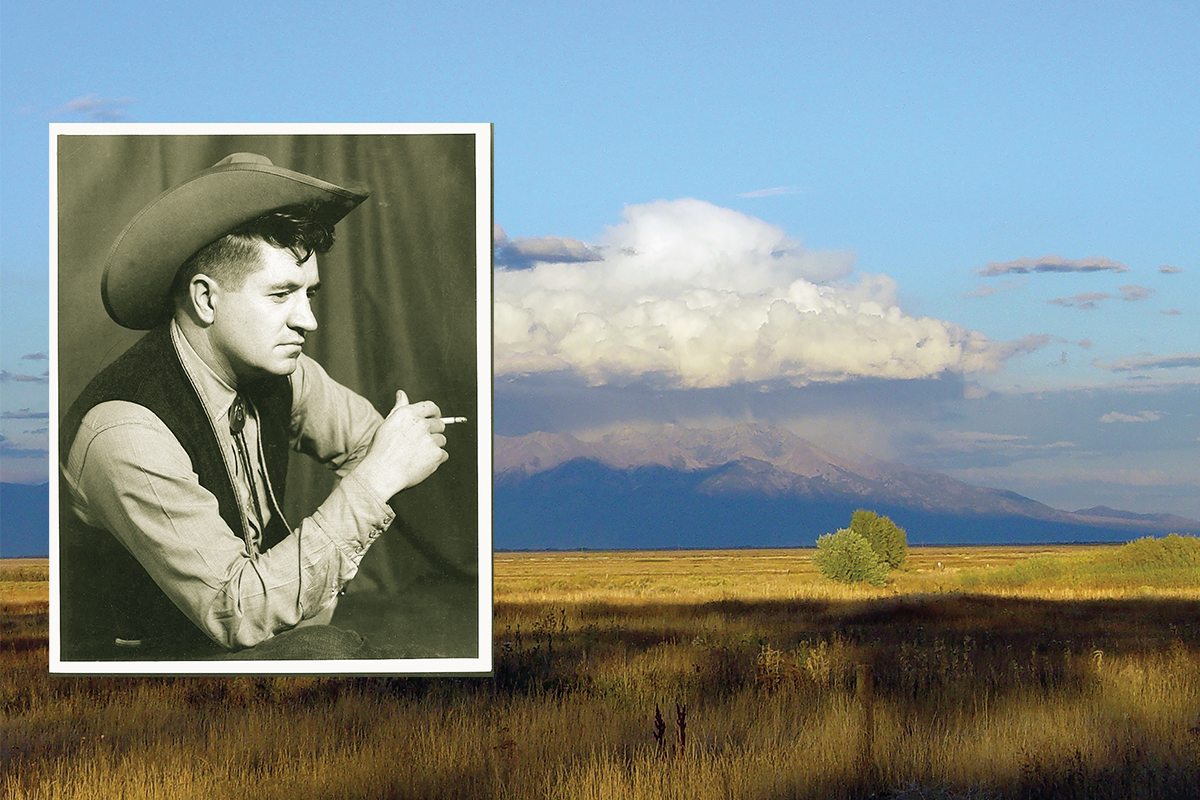

– SANGRE DE CRISTO MOUNTAINS PHOTO COURTESY USFWS/MAX EVANS PHOTO BY MARTIN SCHAEFER, 1960 COURTESY MAX EVANS –

Technically, Chama isn’t in the Hi Lo Country, but it’s a great starting point for this Renegade Road trip, as this town defines just how important Ol’ Max Evans was to New Mexico.

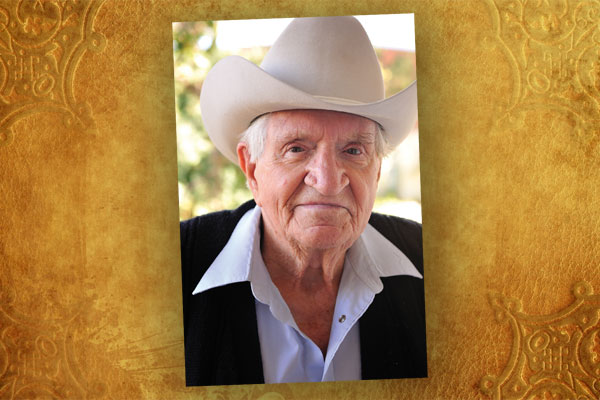

Who’s Ol’ Max Evans? A literary legend—once dubbed “a range-land Mark Twain”—he wrote novellas, novels, short stories, biographies and nonfiction books. Hollywood turned two of his works—The Rounders and The Hi-Lo Country (Hollywood added a hyphen)—into post-World War II Western films. He palled around with Sam Peckinpah, when they weren’t beating each other senseless. And he died August 26, three days before his 96th birthday—a long life, but even longer in Max Evans years (let’s call it 1,219).

While Evans wrote about all of New Mexico, the Hi Lo Country was the name he gave the region that shaped him and most of his writings: the windy grasslands, arroyos and buttes that cover northeastern New Mexico and stretch into southern Colorado, the Oklahoma Panhandle and parts of West Texas. “The indomitable spirit of that land should cover the world and beyond,” Evans wrote.

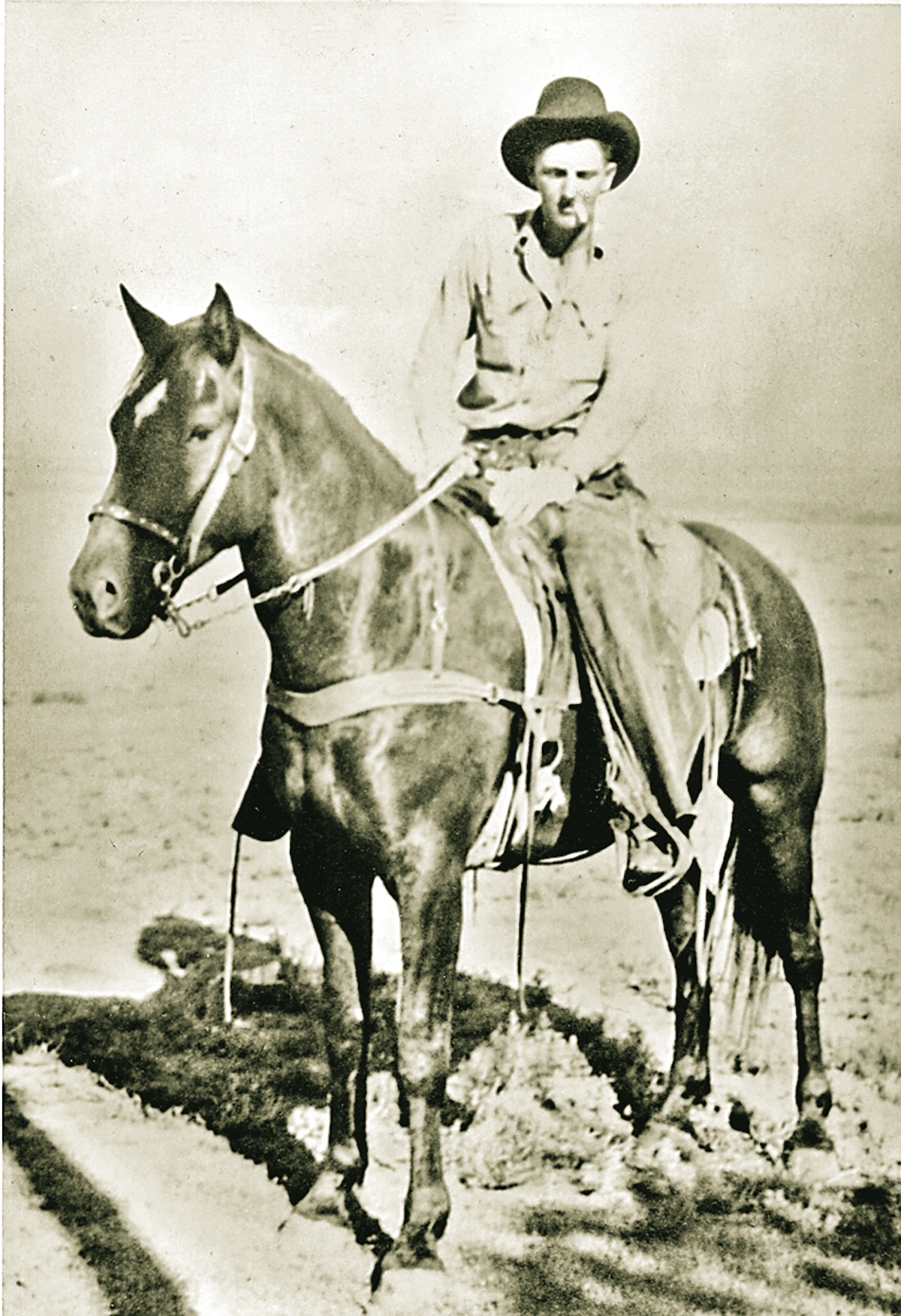

But Evans was more than just a writer. He was a cowboy, wrangler, artist, mystic, smuggler, actor (The Ballad of Cable Hogue), producer, under-the-table script doctor and World War II veteran who fought in France from D-Day until a mortar explosion sent him home before the Battle of the Bulge.

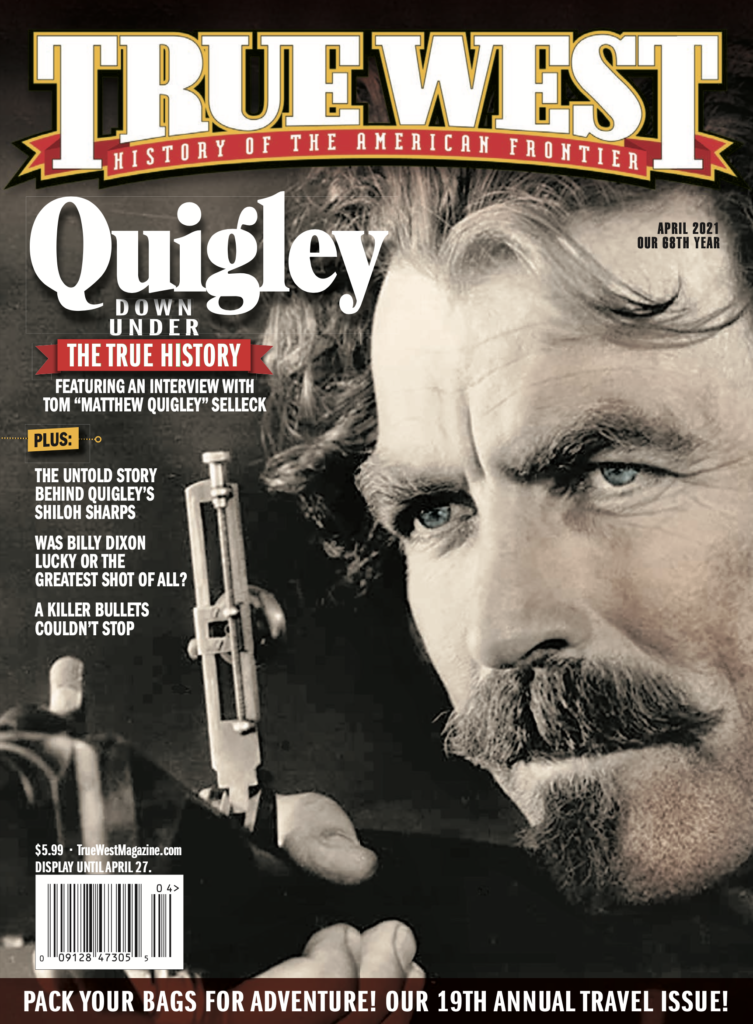

I’m in Chama because Evans also helped found the New Mexico Film Commission in 1968. America’s first state film commission lured The Good Guys and the Bad Guys (1969), starring Robert Mitchum, George

Kennedy and the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad.

The narrow-gauge railroad was built in 1880 to connect the silver mines in the San Juan mountain range in southwestern Colorado. Preservationists saved the railroad in 1970, and since 1971, tourist trains have run out of Chama and Antonito, Colorado.

Evans also made sure The Hi-Lo Country (1998) was filmed in New Mexico, too.

– ALL PHOTOS BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED –

Taos

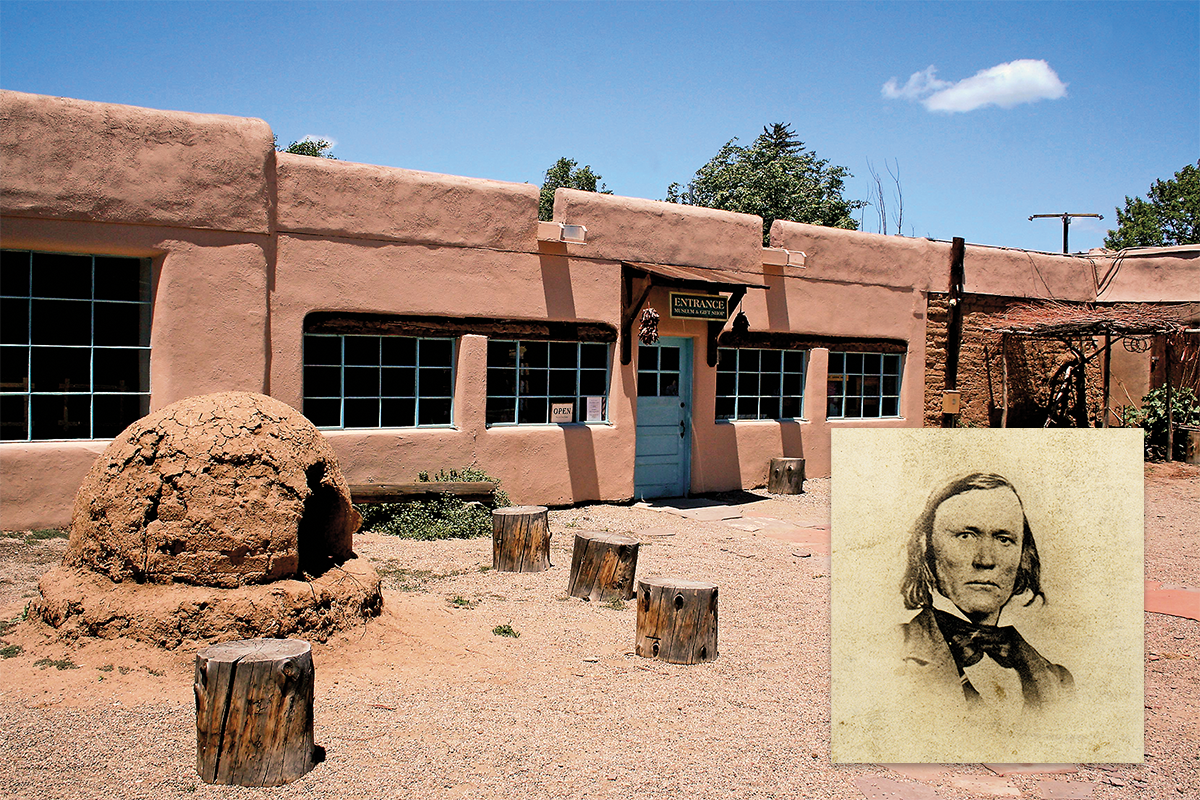

But Ol’ Max’s career really began in Taos, where he settled in the late 1940s to paint, mentored by Potawatomi artist Woody Crumbo. Artists had been flocking to Taos since the 1890s, and the Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915, included Ernest Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp and Eanger Irving Couse. Art still thrives here (Taos Art Museum at Fechin House, Harwood Museum of Art, Millicent Rogers Museum) as does Western history (Kit Carson Home and Museum, Martinez Hacienda).

Evans’s oil-on-canvas Normandy Night Fire landed him into a juried art show. He took his soon-to-be wife (and editor), Pat, to the show on their first date. They married in 1949, and when he decided to become a writer, Pat toughed it out.

– CARSON HOME BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS/KIT CARSON PHOTO COURTESY TRUE WEST ARCHIVES –

A short story collection, Southwest Wind, was published in 1958, and his first book- length work, Long John Dunn of Taos, followed in 1959. But it was the next novel, The Rounders (1960), that launched his career. The Hi Lo Country (1961) found its way to Peckinpah, whose options on it over several years kept the Evans family out of poverty. Evans’s last novel, The King of Taos, a comic look at life in Taos after WWII, was published shortly before his death.

Sangre de Cristos

Before moving to Albuquerque in the 1960s, Evans still dallied in other enterprises, some legal, some not. Mostly, he prospected— Questa became a key setting in Evans’s Now & Forever (2003)—and he explored the mountain towns of Red River (Red River Schoolhouse and Orin Mallette Cabin are designated heritage buildings), and probably even the ghost town of Elizabethtown, about five miles north of Eagle Nest (Enchanted Circle Gateway Museum & Visitor Center) and Cimarron (Aztec Mill Museum). Cimarron, which attracted Western figures including Carson, Black Jack Ketchum, Lucien Maxwell and Clay Allison, became one of the models for Evans’s fictional cowtown, Hi Lo. The northern New Mexico towns of Des Moines and Springer also morphed into Hi Lo: “all small, wind-scoured hamlets in New Mexico that prosper or suffer with the price of beef or copper and other ores,” Charles Champlin wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 1999.

Raton

Raton (Raton Museum), maybe the Hi Lo Country seat just south of Raton Pass, also played a part in Evans’s career. He cowboyed a few times for the nearby T.O. Ranch, and he wound up in the Raton jail after trashing the Big Chief Bar.

The brawl happened in the late 1940s when Ol’ Max, a new pal and the pal’s monkey were drinking. Robert Nott, who cowrote Evans’s Goin’ Crazy with Sam Peckinpah and All Our Friends (2014), told the story in 2014 for Pasatiempo, the Santa Fe New Mexican’s weekend arts supplement:

“Evans, his new buddy, and the buddy’s pet primate were all having a friendly drink. (In those days, monkeys were allowed in Raton bars.) Then the spunky simian sprang onto a nearby table, where a couple of would-be society matrons and their big bruiser boyfriends sat. The liquor bottles toppled over, someone got whiskey on their nice white dress, the two angry suitors began cussing out the monkey and, well, Evans had to step in, all for the honor of a monkey. Fists started swinging and furniture went flying. Evans and his pals got a night of free board in the local jail. The next day, Evans returned to the Big Chief Bar and paid for the damages.”

This trip could end here, but there’s one more stop, roughly 36 miles east on U.S. 64. It’s where The Hi Lo Country, Ol’ Max’s most personal novel, began.

Before moving to Taos, Evans had owned a small spread, day-working as a cowboy to make ends meet, and befriended cowboy Wiley “Big Boy” Hittson Jr., a decorated

– PHOTO COURTESY MAX EVANS –

WWII vet. On November 5, 1949, Hittson’s younger brother shot and killed “Big Boy.” The novel and movie open with the funeral and burial. The real “Big Boy” still rests in the lonely, windswept Des Moines Cemetery. “I watched them lower Big Boy Matson into his grave,” The Hi Lo Country begins. “It was a large coffin, and yet I half expected it to burst apart from the weight and size of the man. Not only his physical bigness but from the whole of his being.” Ol’ Max Evans wasn’t a big man, but he was a Western literary giant.

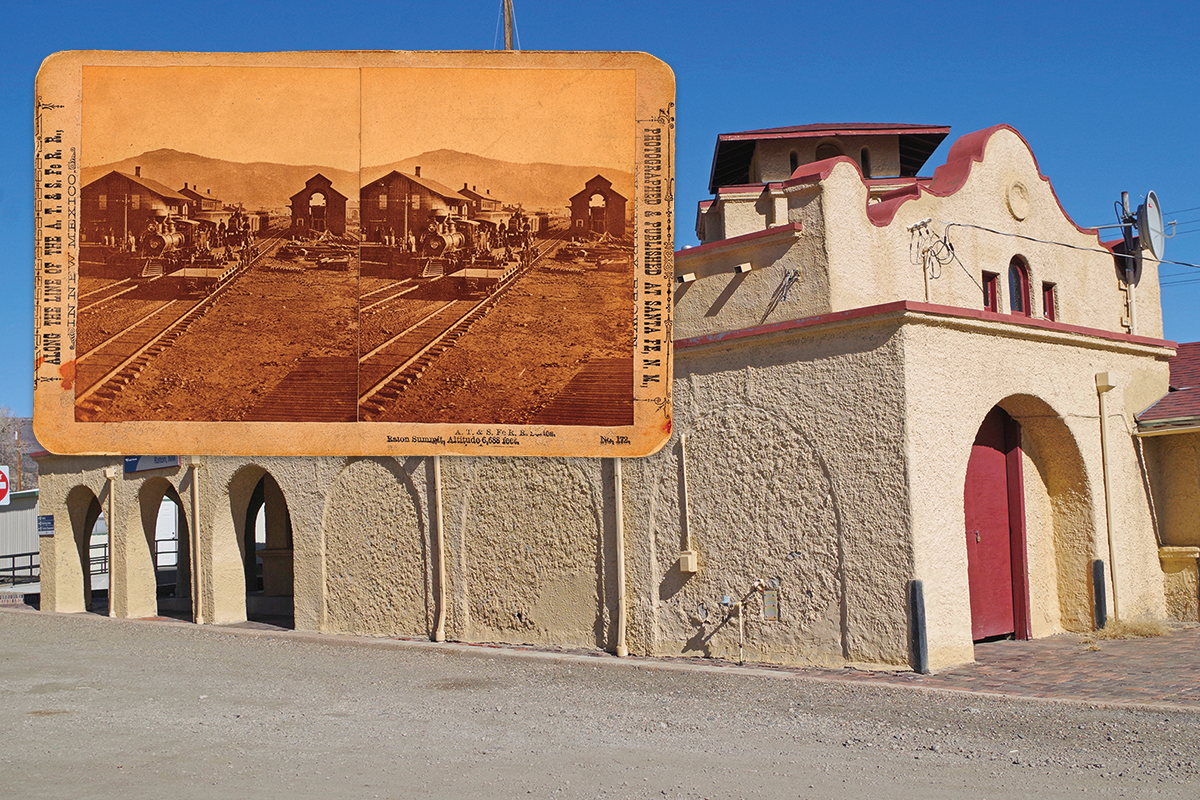

The first Santa Fe trains chugged into Raton in 1878.

¬– HISTORIC RATON STATION COURTESY NYPL DIGITAL COLLECTIONS/SFRRDEPOT COURTESY JOHNNY D. BOGGS –

A Wide Spot in the Road

ST. JAMES HOTEL

Abraham Lincoln never stayed in the St. James Hotel in Cimarron, New Mexico, but he probably would have had he lived longer. After all, Abe knew how well the owner, Henri Lambert, could cook. Lambert was the president’s personal chef. After Lincoln’s assassination, Lambert went west, landing in Elizabethtown. But he didn’t strike it rich until he came to nearby, rip-roaring Cimarron, where the Frenchman built Lambert’s Inn, home to 43 rooms, a restaurant and saloon and, reportedly, 26 or more murders. Bullet holes can still be found in the dining room’s ceiling at what’s now the St. James Hotel, with several restored rooms in the original building and more in a modern annex. Known for its food, lodging and a history that includes having the likes of Clay Allison, Black Jack Ketchum and Buffalo Bill Cody under its roof, the St. James today entertains aficionados of Western history. ExStJames.com

GOOD EATS AND SLEEPS

GOOD GRUB:

- Chili Line Depot, Tres Piedras

- The Burger Stand @ Taos Ale House, Taos

- Red River Brewing Company & Distillery, Red River

- La Cosina Café, Raton

GOOD LODGING:

- Elkhorn Lodge, Chama

- La Doña Luz Inn, Taos

- Laguna Vista Resort, Eagle Nest

- St. James Hotel, Cimarron