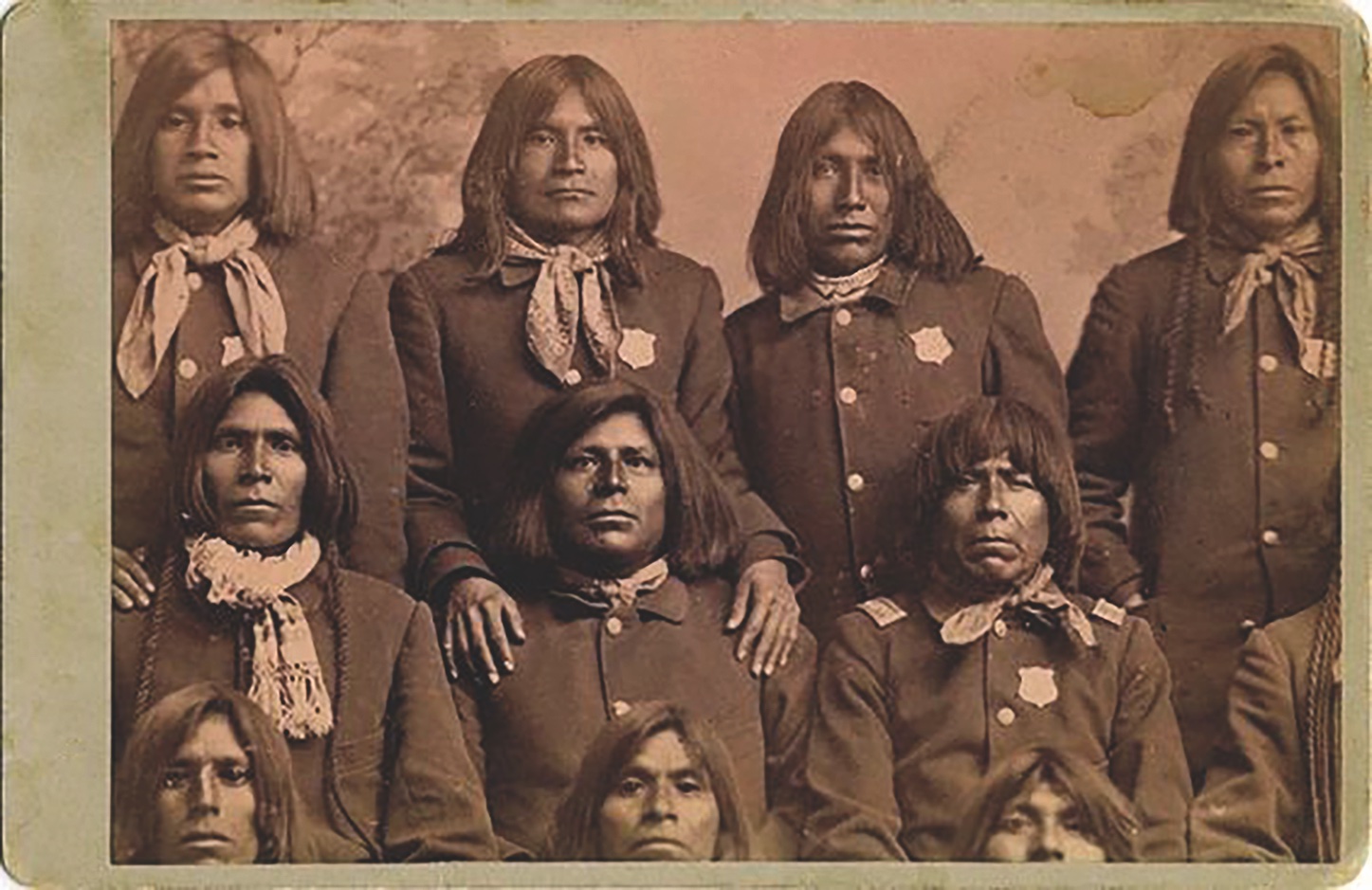

Early American Indian Police played a strong role in the settlement of the West.

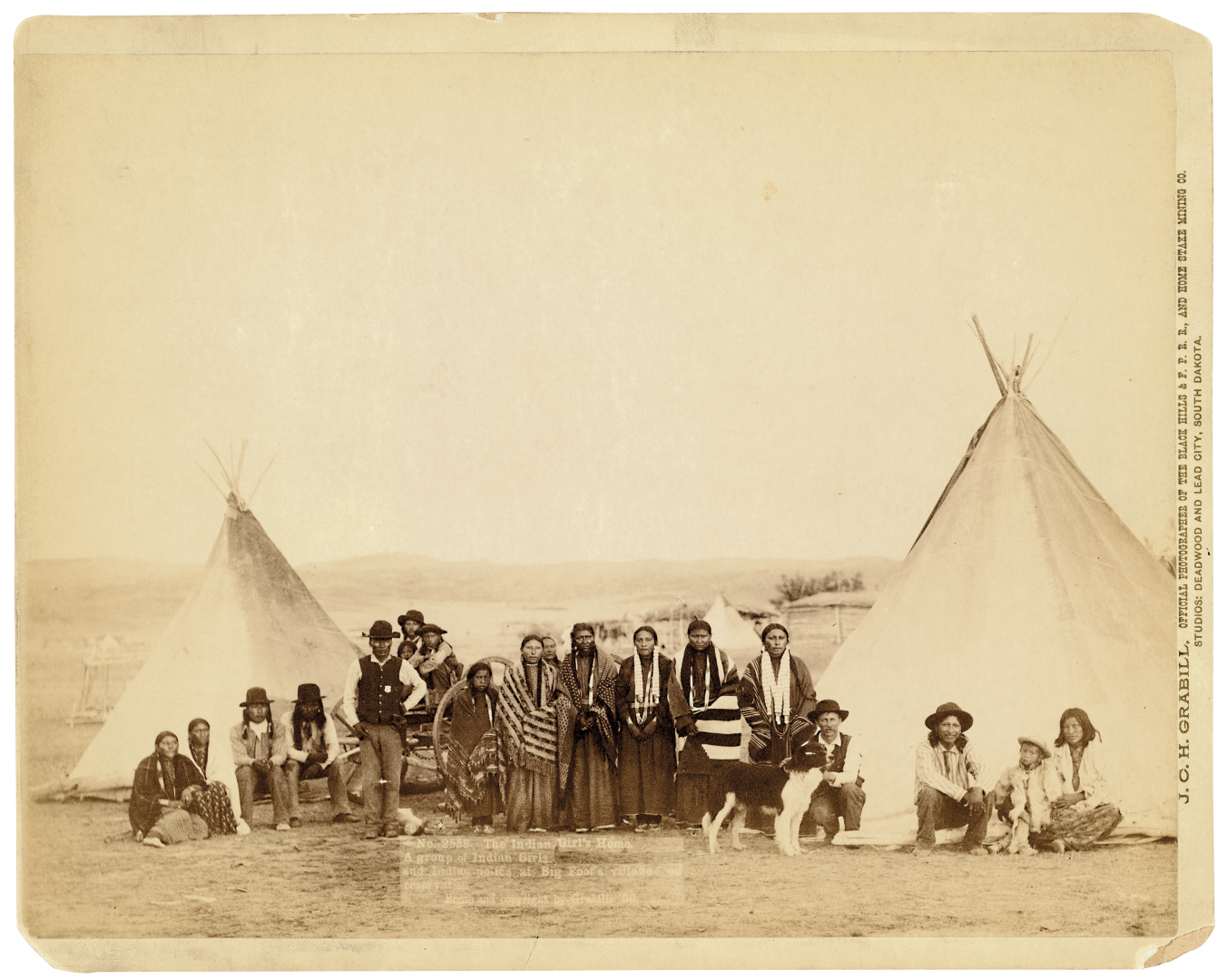

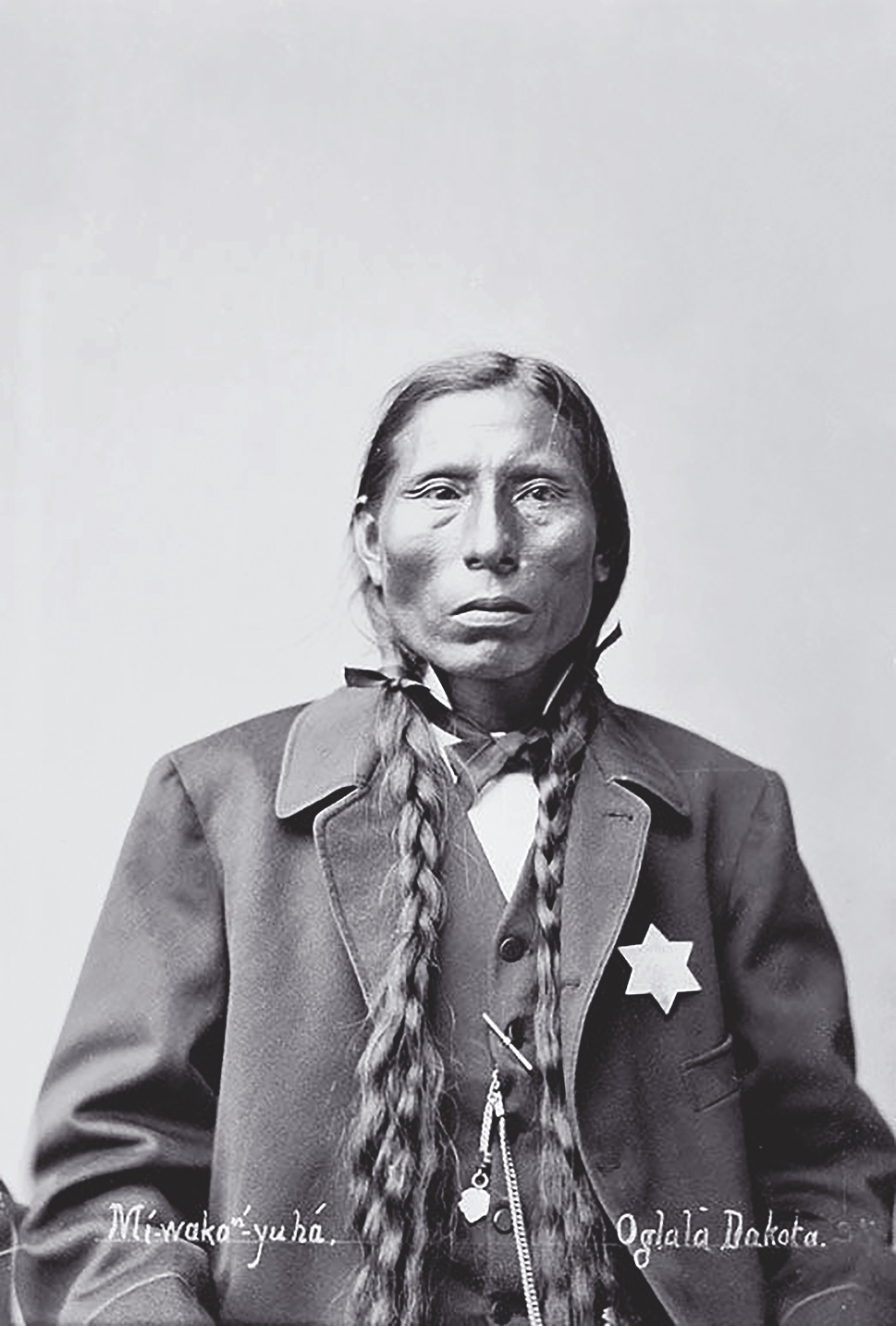

Before recorded history, American Indians practiced some form of policing. The Sioux possessed the most organized tribal police society called the Akicita, also known as warrior societies, policing societies or whip bearers. Their duties included general social control. They especially played an active role during the annual hunts, keeping tribal members from starting too early or making unnecessary noise and controlling stragglers. Once the buffalo hunt ended, they ensured the equal distribution of meat and probably intervened in discussions of who could claim a specific kill.

But the Cherokees created the original tribal police force recognizable to Europeans. By 1779 “Regulating Companies” came into being mainly to deal with horse thefts, some by the whites. In 1808 the Cherokees appointed sheriffs and a group of small companies called the “lighthorse” who patrolled the villages and enforced the first written code promulgated by an Indian tribe.

“I have appointed a police, whose duty it is to report to me if they know of anything that is wrong.”

—Thomas Lightfoot, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1869

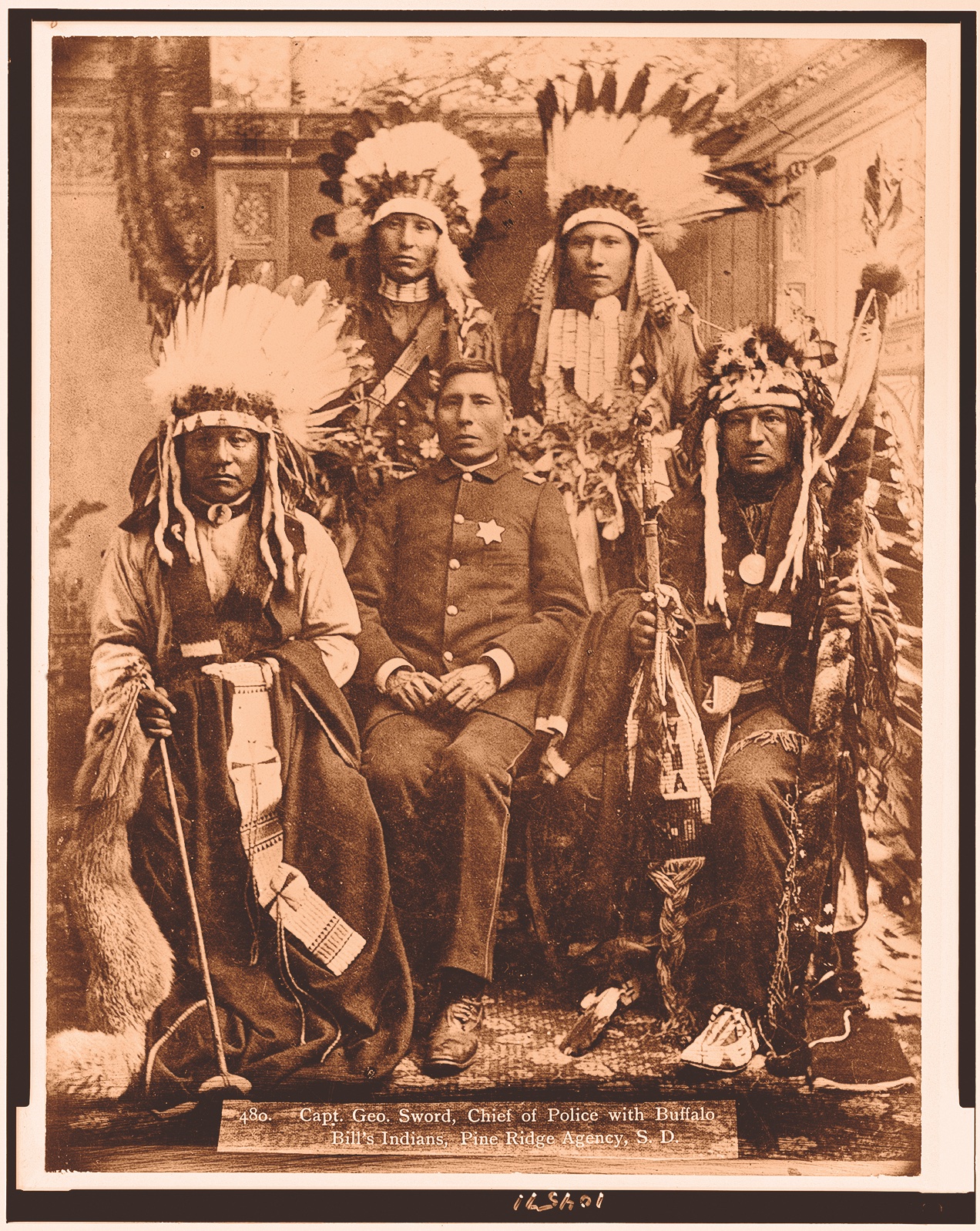

The First Indian Police

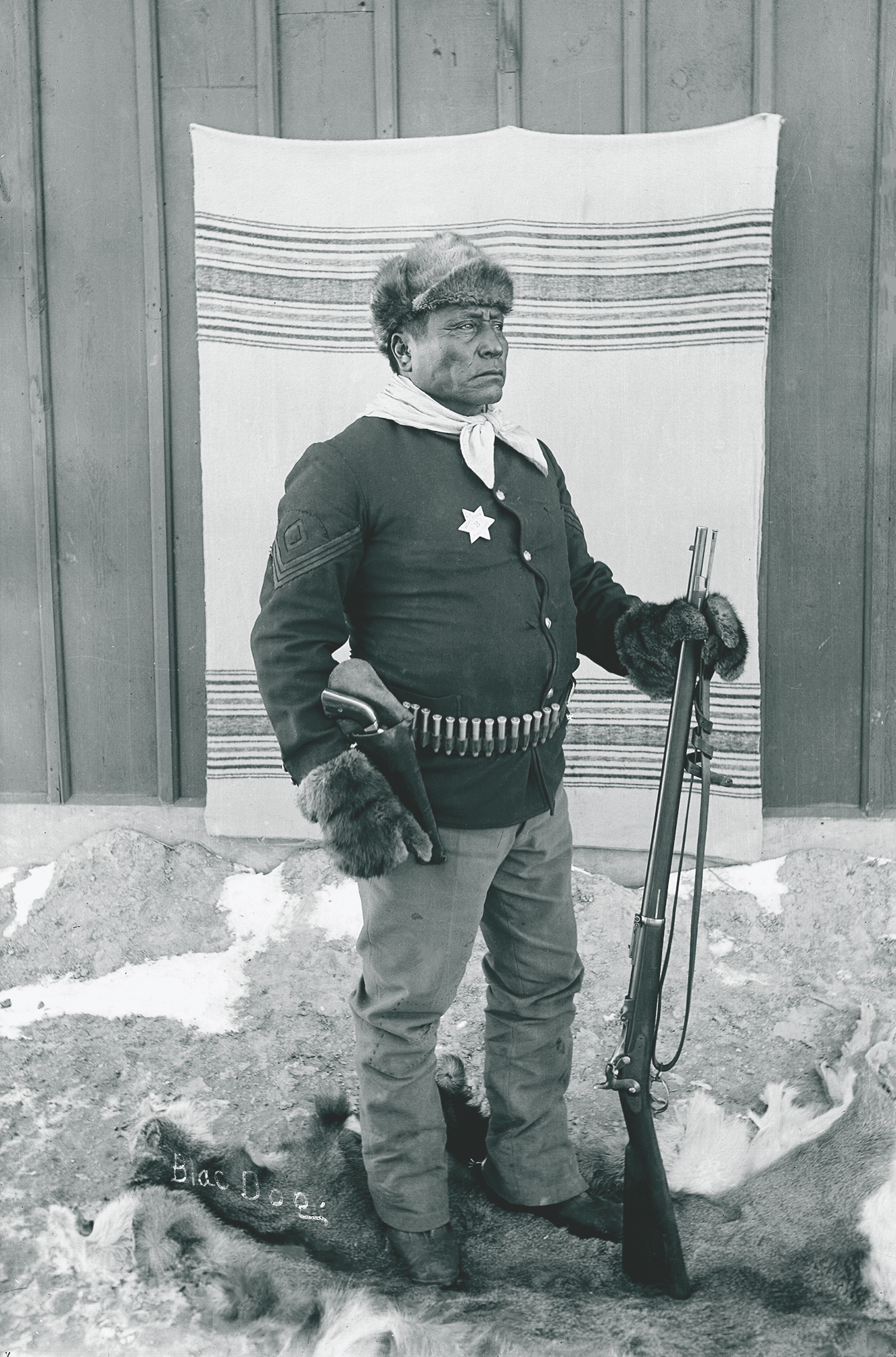

Nearly a century later, in 1865 at Fort Laramie, some Sioux wishing to remain aloof from growing conflict with the whites on the Northern Plains, set up camp east of the post. They received rations “for which, in return, they were to serve as scouts and camp police. Trader Charles Elliston commanded the paramilitary unit….” During May “some of Elliston’s police apprehended the Oglalas Two Face and Black Foot,” who the local commander, Col. Thomas Moonlight of the 11th Kansas Cavalry, subsequently hanged.

By 1869, Thomas Lightfoot, United States Indian agent to the Iowa and the Sac and Fox tribes in Nebraska, established a federally sponsored Indian police. Agent Lightfoot acted in response to a major shift in United States policy toward the Indians. Instead of viewing tribal peoples as sovereign nations, the evolving approach meant the government would engage with Native people as individuals. In 1869, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely S. Parker (U.S. Grant’s chief of staff at the end of the Civil War) expressed this view when he urged an end to treaty-making.

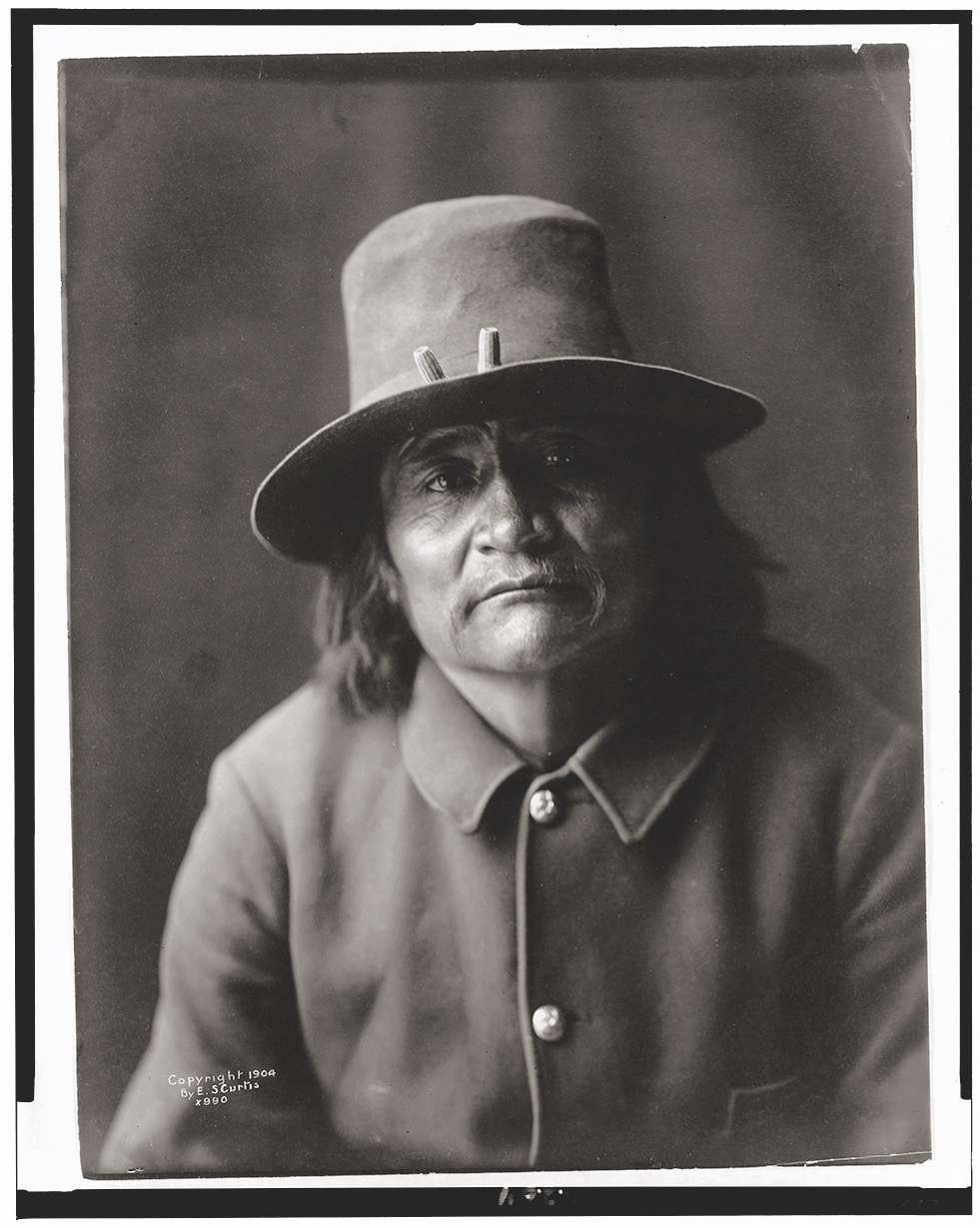

The Navajo Police

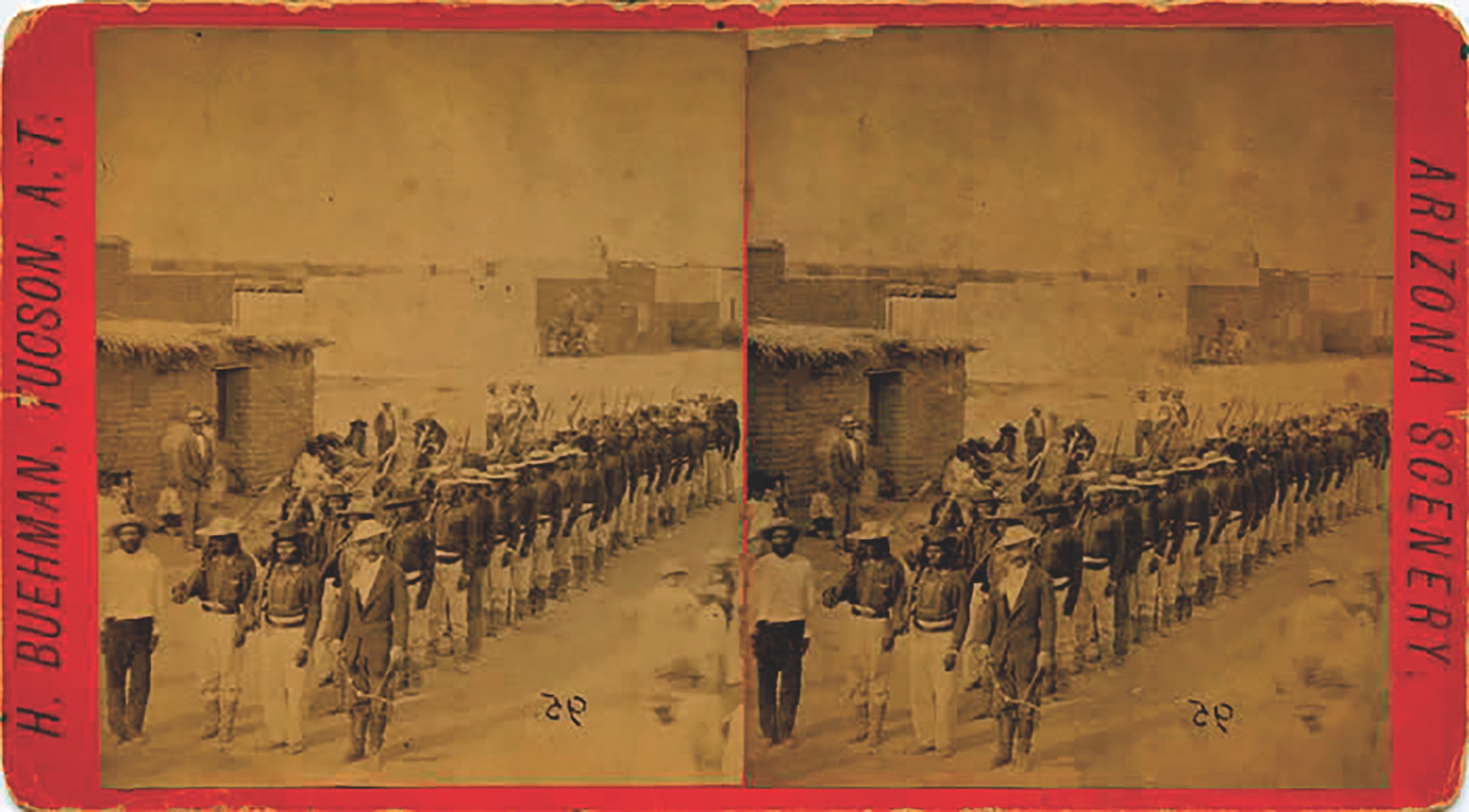

While policy waxed and waned, Lightfoot and others improvised. For example, in 1872, Agent William Arny commissioned Navajo police to guard the reservation borders and control cattle- and horse-rustling, while Special Indian Commissioner for the Navajos Gen. Oliver O. Howard organized a cavalry of 130 Navajos to guard reservation boundaries, arrest thieves and recover stolen stock. The force successfully recovered 60 head of stock in three months and continued to exist despite orders from Washington that it be disbanded.

In fact, although they were effective and served as a model for others to follow, the Navajo units were disbanded by the Department of the Interior partly because they lacked official funding or approval. A similar, long-lasting initiative, however, took root among the Apaches in Arizona.

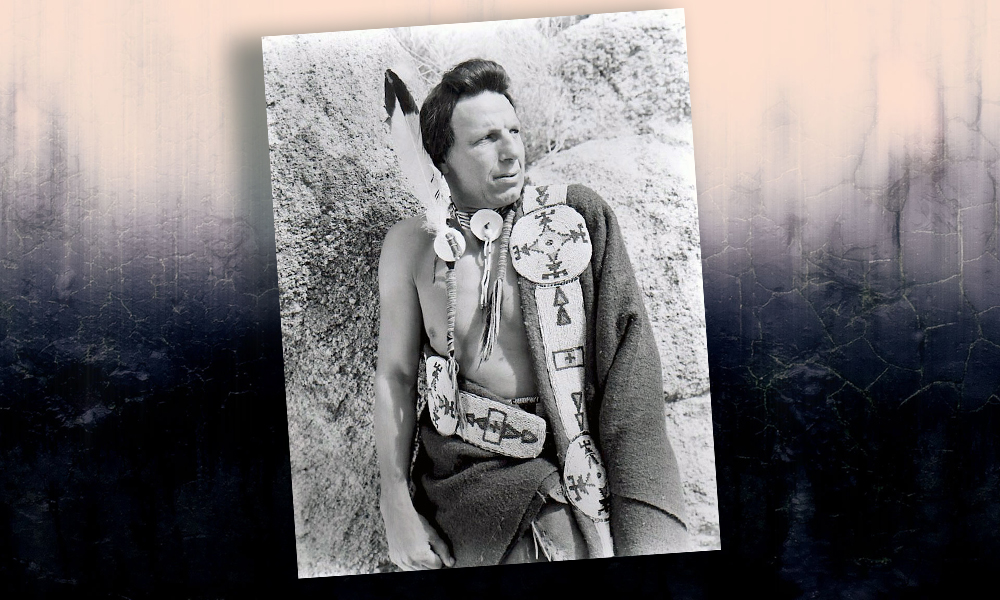

John Clum Arrives

On February 26, 1874, John P. Clum received an appointment as Indian agent for the White Mountain Apaches at the San Carlos Reservation. There he was charged with the well-being of 4,500 Apaches. Recently discharged from the U.S. Army Signal Corps in nearby New Mexico, he arrived at San Carlos on August 8, which, according to his son, Woodworth Clum in Apache Agent; the Story of John P. Clum, opened “a new era in southwestern Indian affairs.” The 22-year-old New Yorker “soon demonstrated his innovative character,” although his “cocky” demeanor alienated many important Army officers who resented Indian Bureau interference into Arizona matters.

Clum came onto the scene in the wake of the ever-changing approach to settling the “Indian Question” during another experiment by U.S. Grant’s administration dubbed the “Peace Policy.” Several different religious denominations assumed operations of various Indian reservations. The Dutch Reformed Church took on responsibilities for San Carlos, which resulted in the need for a new agent.

Despite “no experience with Indian affairs, based on recommendations of former classmates at Rutgers College, Clum accepted a commission from the church, which also supported his alma mater. His knowledge of the Southwest was limited to a three-year stint” taking meteorological observations in Santa Fe.

Clum travelled to Tucson and from there to the agency. According to Clum’s son, wise heads in that community advised him not to go to San Carlos, warning “Better go back to the farm and save your money as well as your scalp.” He answered, “The Government is paying my traveling expenses so I cannot lose any money by going to San Carlos, and having no hair, I cannot very well lose my scalp.”

When Clum arrived, he was not pleased by what he saw: “Of all the desolate, isolated human habitations! Wikiups [sic], covered with brush and grass, old blankets, or deerskins, smoky, smelly. Lean dogs, mangy, inert. A few Apaches strolling around as wild and vicious as the inmates of an old folks’ home!” The agency office consisted of adobe chinked between small poles. The same poles served as the roof with dried grass as a covering.

Fortunately, Clum was not easily frightened, otherwise he might have resigned after he was shown where an agency employee was stabbed to death, another location by the Indian trader’s store where 5th U.S. Cavalry 1st Lt. Jacob Almy met his death on May 27, 1873, and a third spot where two teamsters were murdered—all by reservation Apaches.

The next morning five Apaches brought a gunny sack into Clum’s office which contained the head of an Indian renegade, an instigator of a recent outbreak. General George Crook, a major proponent of deploying Indian scouts as part of his strike force against Geronimo, had told them they could only return to the agency if they brought in the man. They had not been able to bring him in alive, and could not carry the body, so they brought the head!

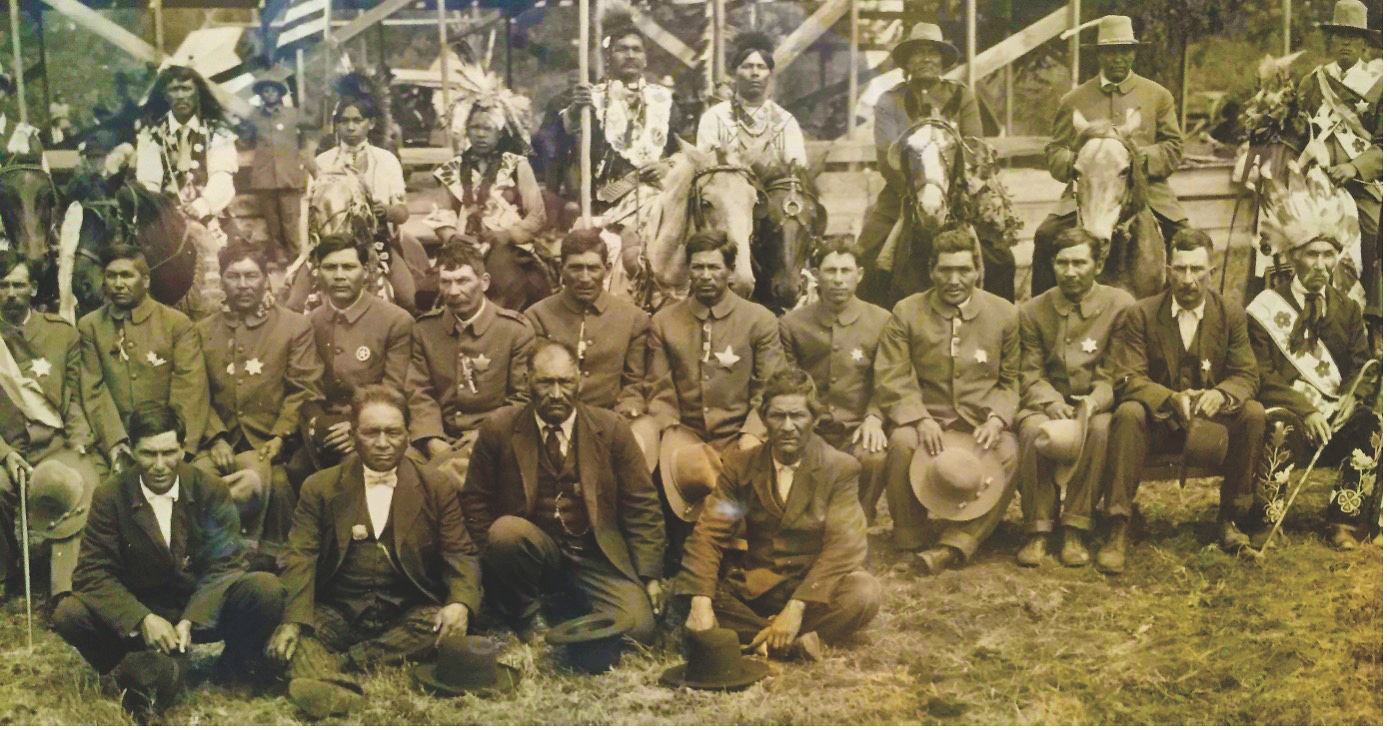

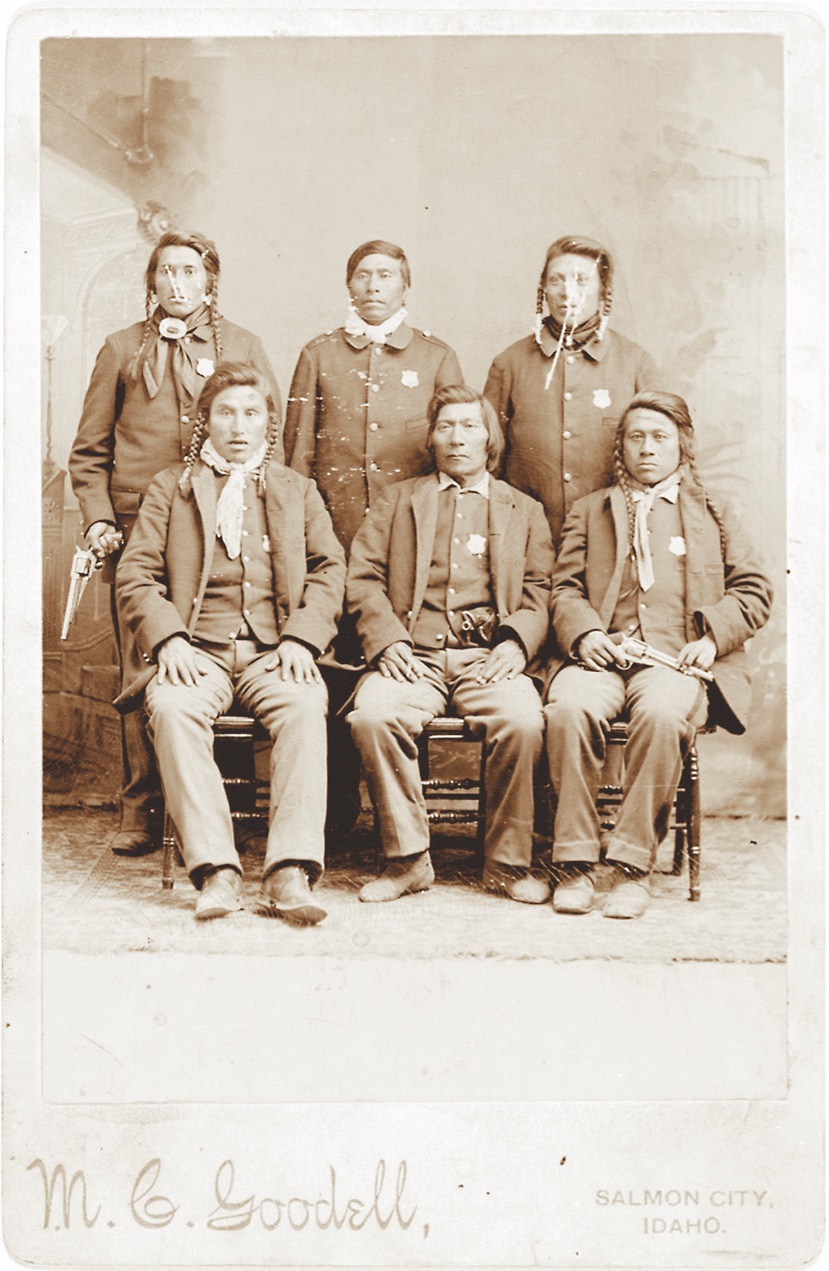

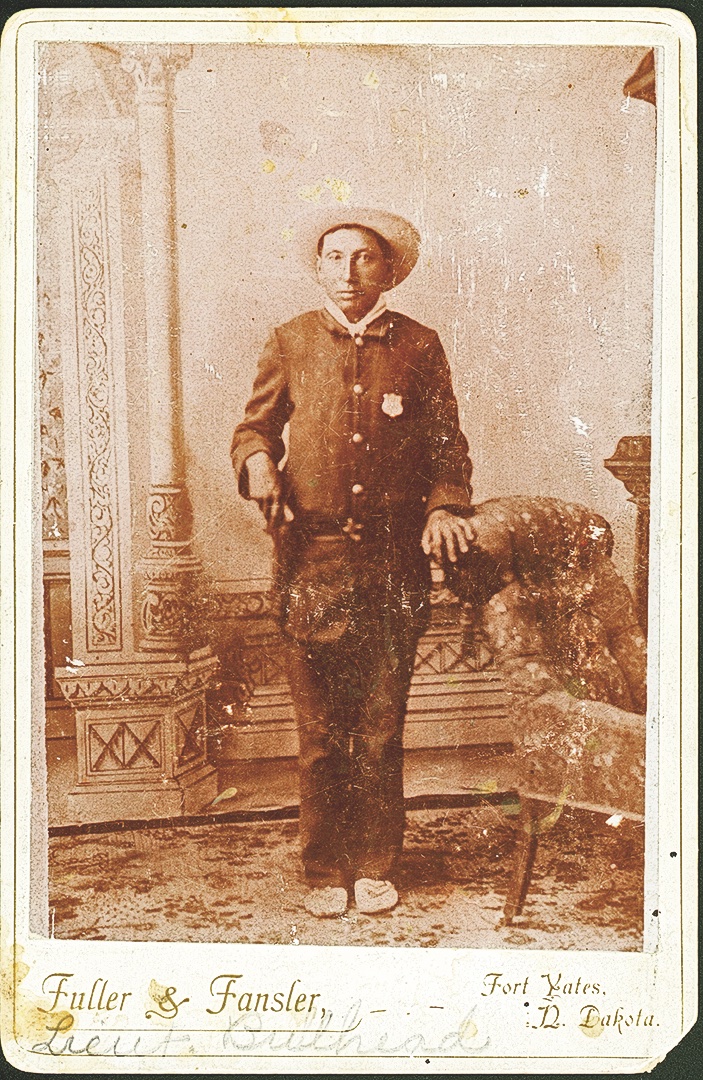

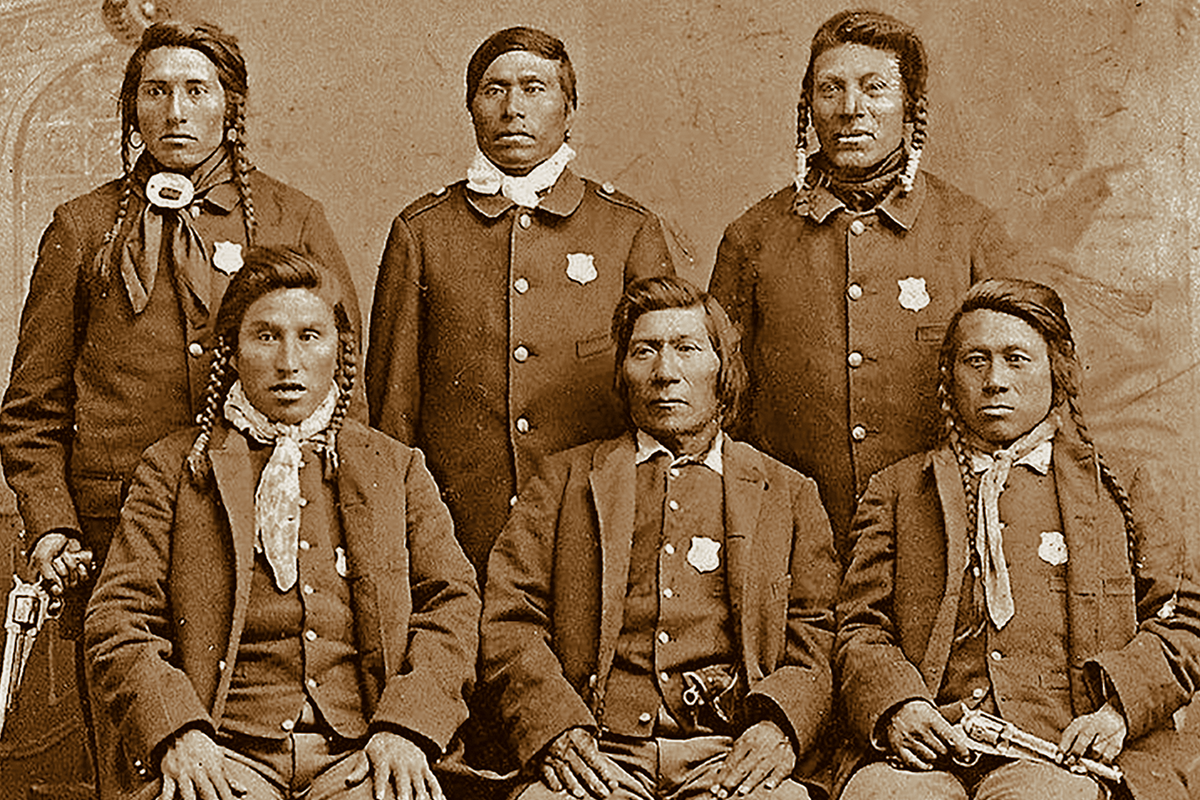

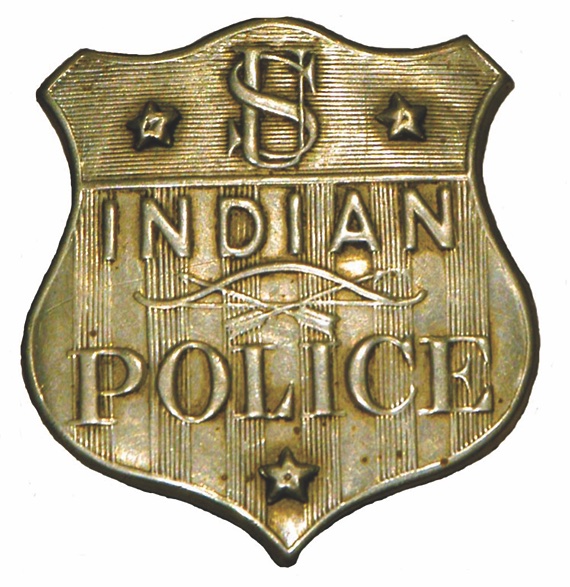

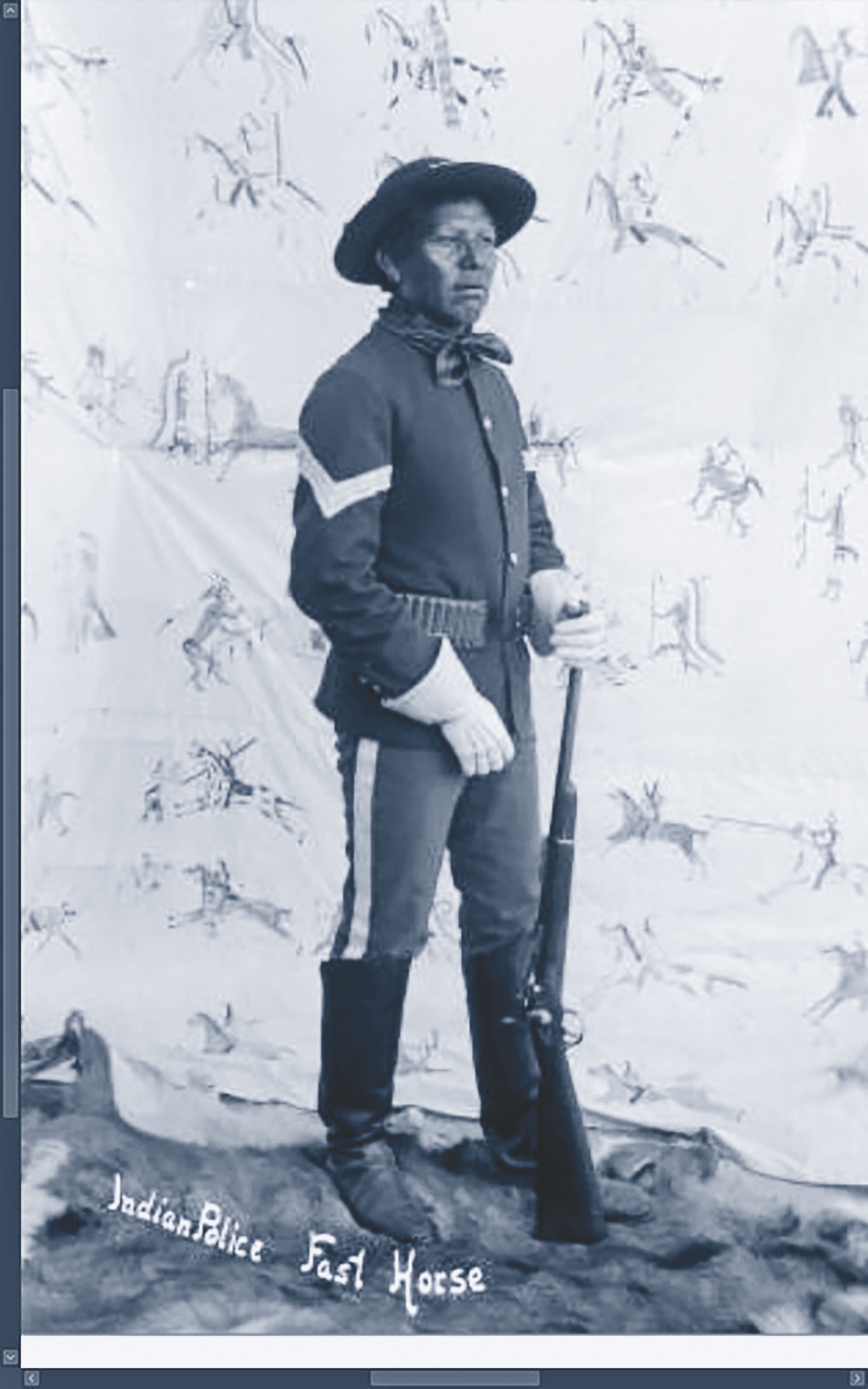

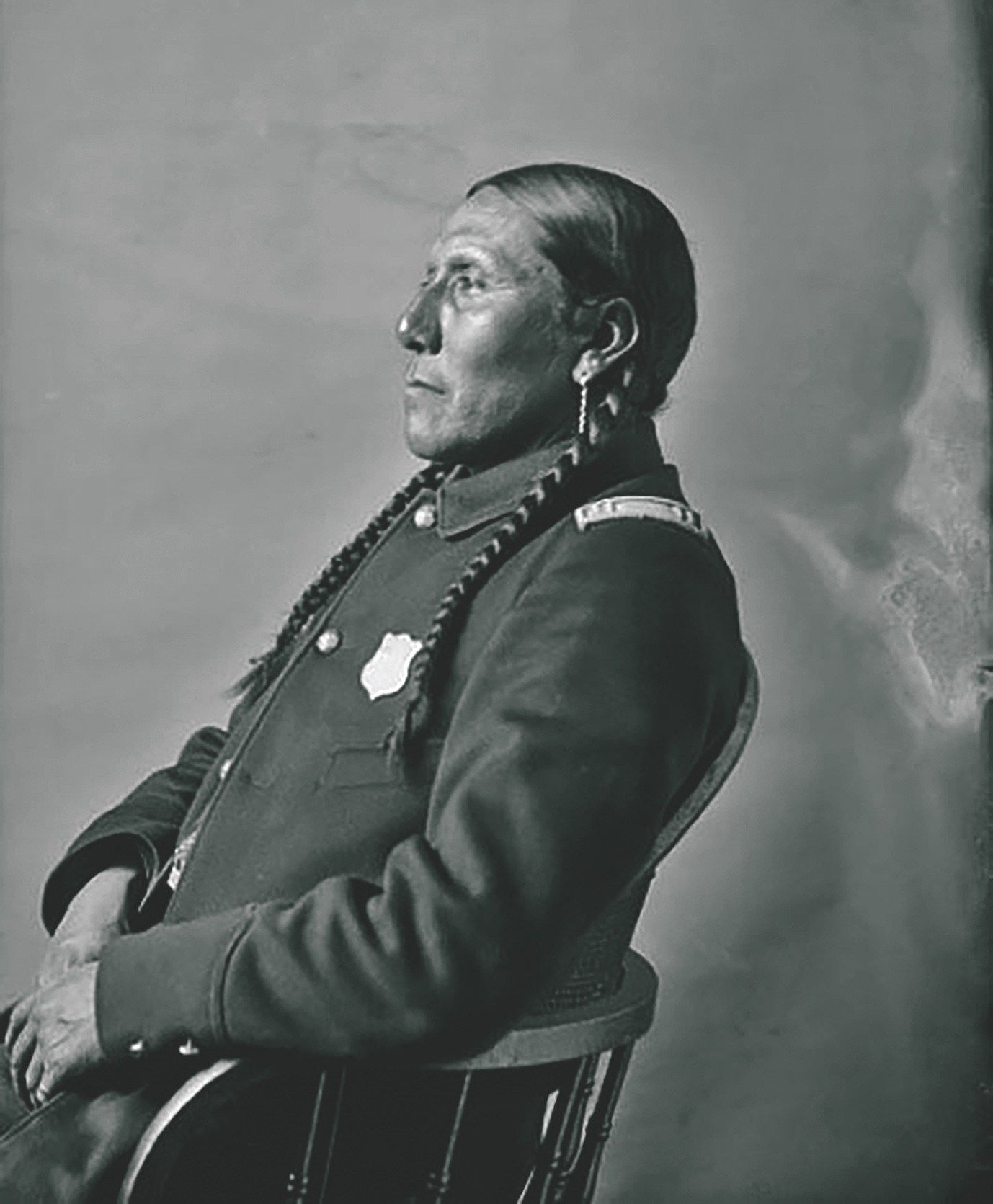

Impressed with Clum’s progress, in 1878, the U.S. Congress approved $30,000 for the employment of 430 privates and 50 officers at various agencies in the West. In 1880, appropriations provided for 480 Indian police; but in 1881, 49 of 68 agencies had Indian police. Nevertheless, in its 1883 session Congress authorized 1,000 privates and 100 officers.

The rest is history. Tribal police remain a vital part of life on reservations to this day.

John Langellier provided this abbreviated excerpt from a work in progress—Indian Scouts, Police, Judges, and Soldiers, based on preliminary efforts by the late Glen Swanson.