Many fans of Westerns, especially the True West maniacs, are guilty of picking them apart for the anachronisms all too often found in such films. I recall having a conversation about the 1969 flick Little Big Man, with a friend who raved on about it, and I answered that although I enjoyed the film, there were several period errors in it. By the time I’d picked it apart, he commented, “Gee, I thought I liked it until I talked to you!”

For the past 40-plus years, I’ve had the opportunity to put in my two cents on a number of movies, television shows and live theater, striving to give Westerns a more authentic look. For my humble efforts, I’ve been honored with Hollywood’s “Cowboy Oscar,” the prestigious Golden Boot Award for achievements in film and live Western entertainment. I’ve also earned the nickname one of “Hollywood’s Hired Guns,” and have been told that the gunleather my Red River company supplied to various prop houses was largely responsible for starting the trend of seeing more authentic holsters and belts on the screen. While serving as a technical or historical advisor/consultant, I’ve learned that one can only advise as to what is correct—not dictate! Producers and directors have the final word, and they are often quick to remind the expert that the production is a dramatic story, not a documentary. Nonetheless, I have done my best to add to the realism of every production.

Hollywood Calls

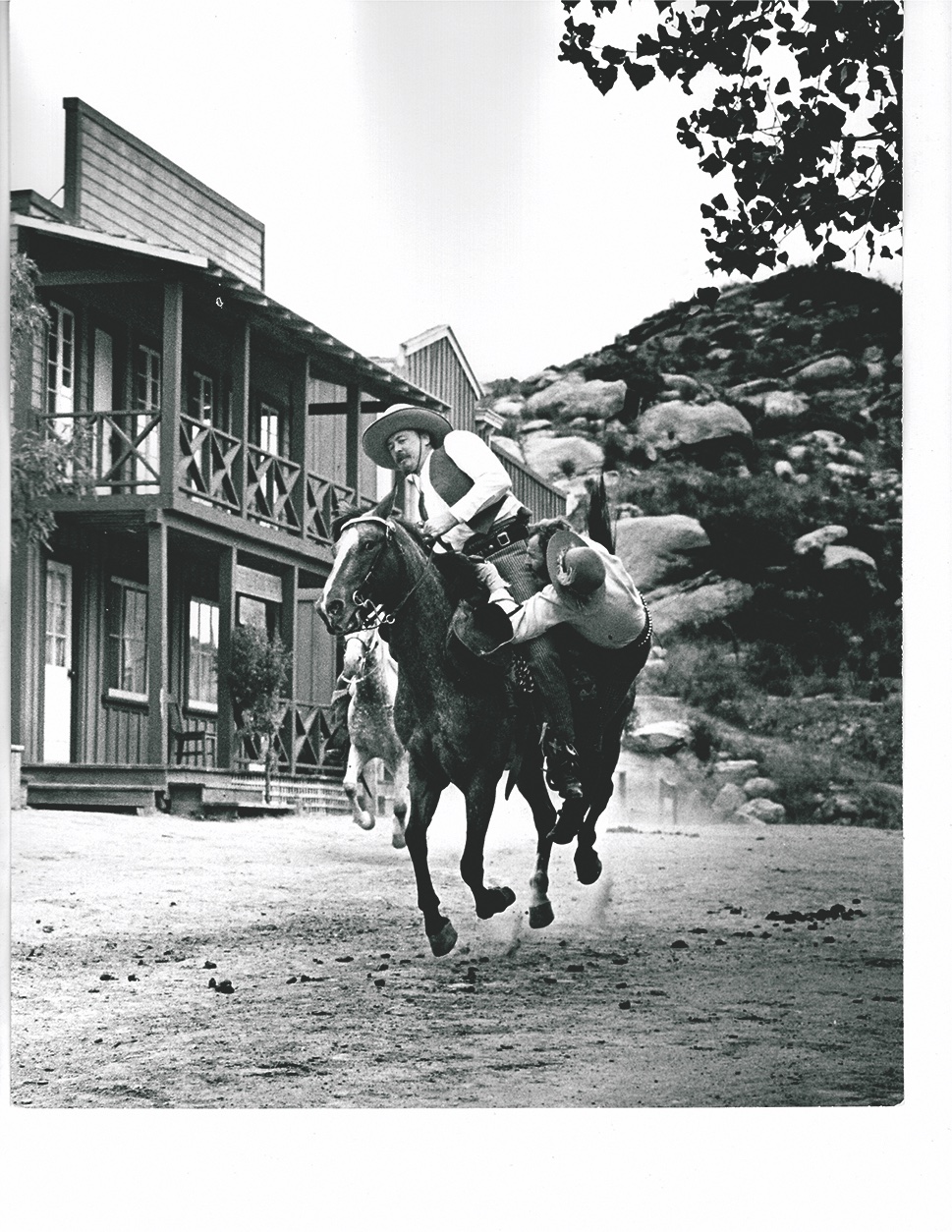

Although I’d produced and performed in live Wild West shows in the U.S. and abroad, and worked on small independent films for years, my career with Hollywood movies and TV started around 1979, when a call came in from my friends at Stembridge Gun Rentals, then located on the Paramount movie lot. My relationship with them had begun years before, when I obtained firearms from them for use in the Wild West shows I performed in around the globe.

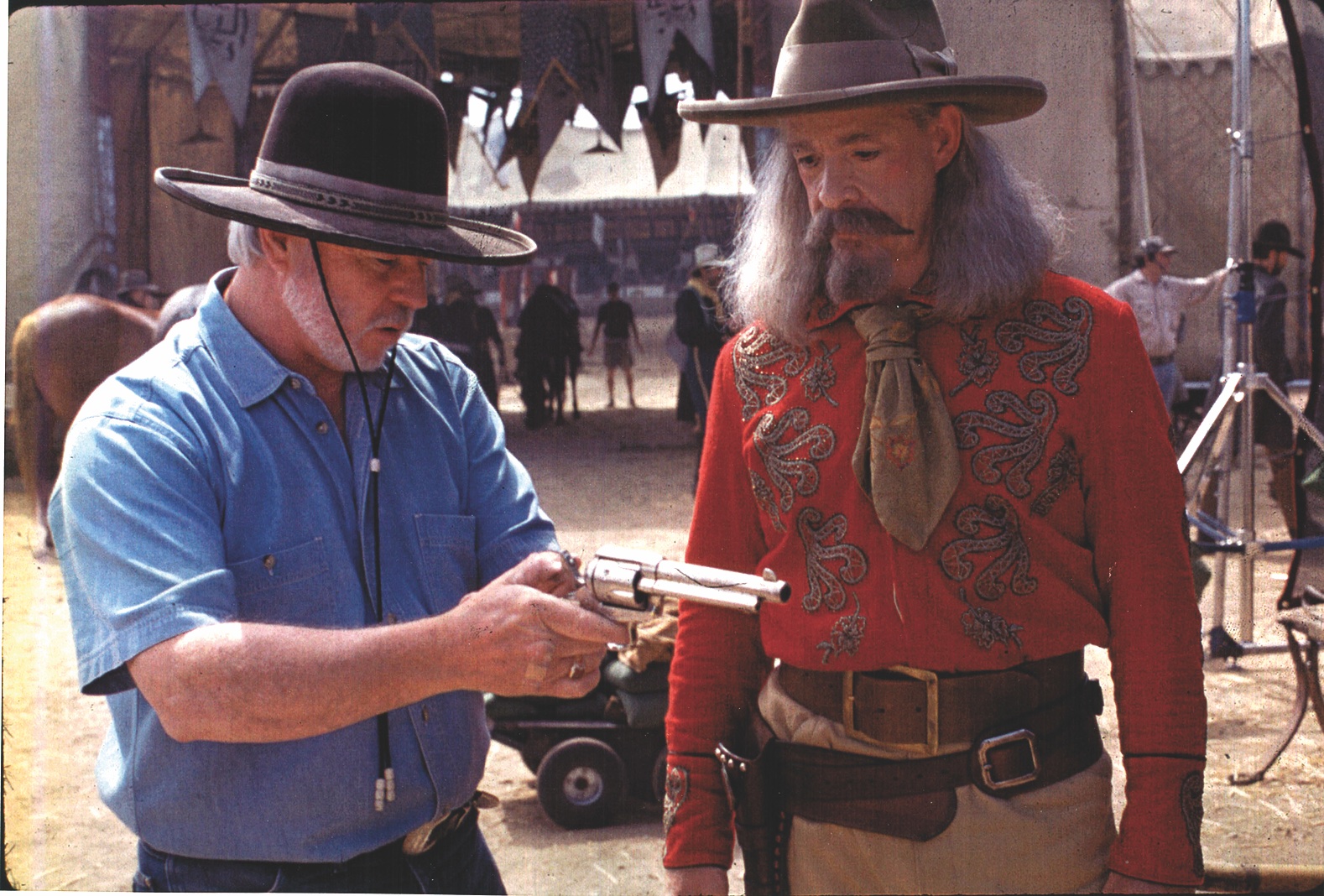

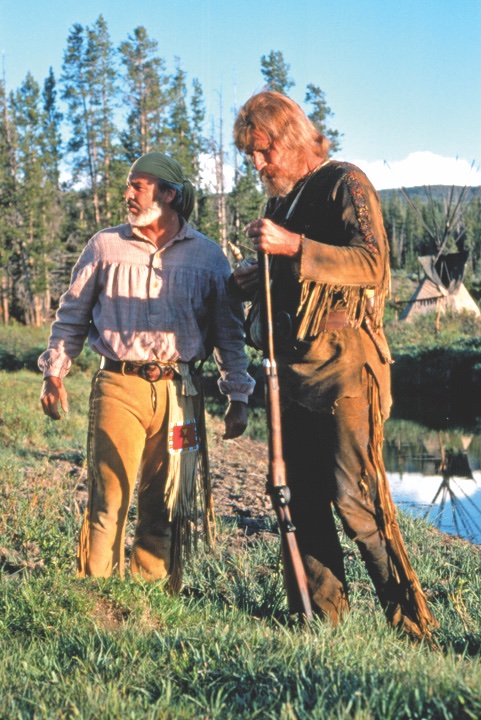

When I was the black powder editor at Guns & Ammo Magazine (G&A), Syd Stembridge called and asked if I could help prop man Bud Shelton select some authentic firearms for Charlton Heston’s then-latest movie The Mountain Men (1980). Bud had purchased several commercially produced, so-called “Hawken” muzzle loading rifles, but they were too modern looking with their polyurethane coated stocks, short blued barrels and brass furniture. Unfortunately, Shelton said he’d already purchased them and had to use them. When I suggested that I knew an artisan who could give them a proper 1830s look, he agreed to have them “uglified.” The guns were sent to my longtime pal Frank Costanza, who within about ten days, transformed these modern-looking smokepoles into what looked like well-used, cut-down, tack-decorated with rawhide repairs, frontier-era Plains rifles—the real deals!

Everyone was so pleased with how authentic these guns now looked, that I was asked to train Heston in the use of muzzleloaders. Jumping at the chance to meet and work with one of my favorite actors, this black powder enthusiast was soon found on a reserved firing line at Angeles Shooting Range, in northeast L.A., showing the man who portrayed Moses, El Cid, Andrew Jackson and so many other historical icons, how to manage my Green River Rifle Works Hawken and a caplock pistol. As an added bonus, Director Richard Lang invited me to be a mountain man extra in the movie’s rendezvous sequence, and eventually, I wound up traveling to the Jackson Hole, Wyoming, location for about 10 days to do some additional coaching and background work with a passel of muzzle-loading amigo extras. My involvement became a lead story in G&A, and a featured spot on ABC-TV’s The American Sportsman. Incidentally, much credit for the overall authentic look and feel of that fur-trade era movie goes to friend and renowned Western artist, Jerry Crandall, and his wife, Judy, who were technical consultants and were present during filming.

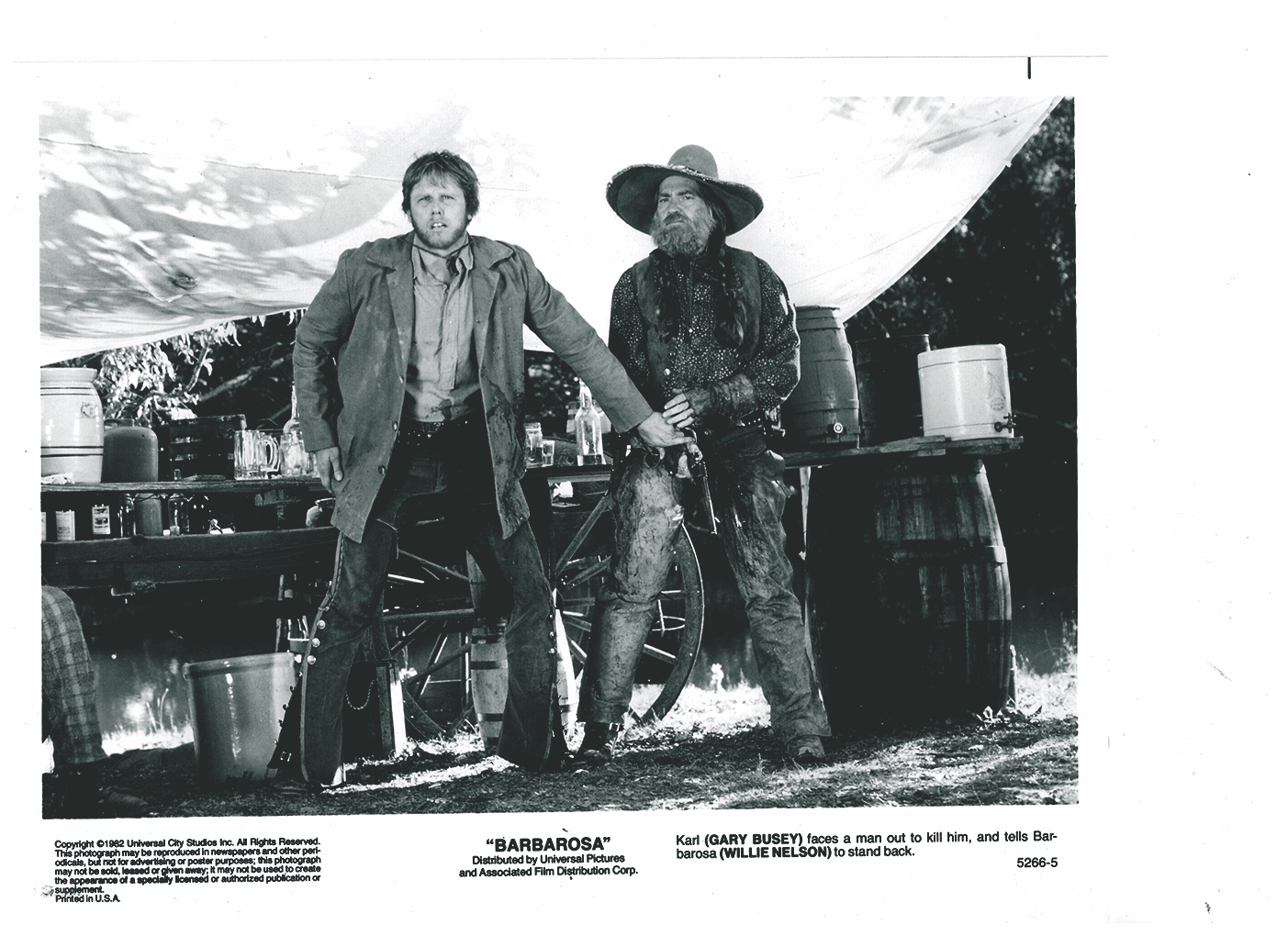

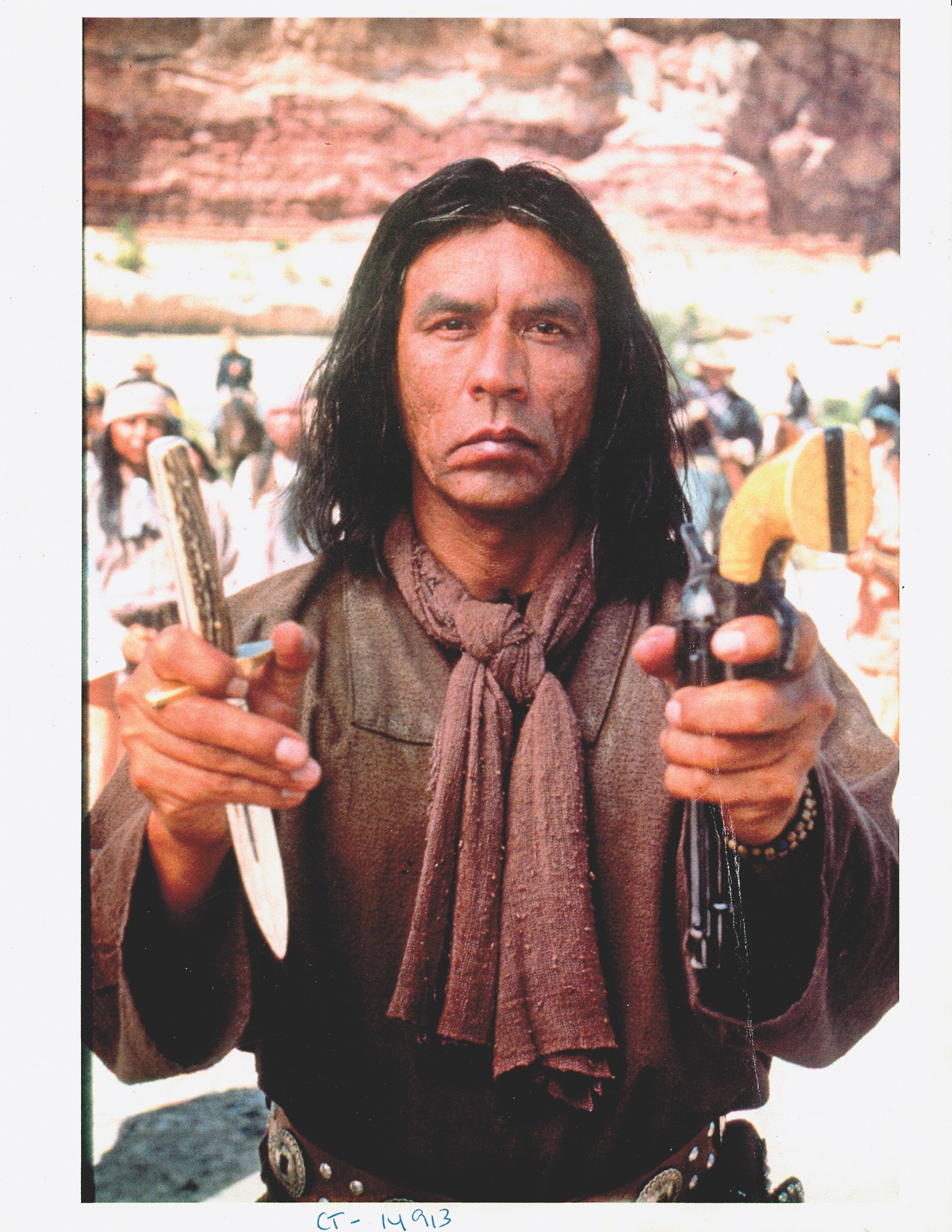

While I worked at G&A, calls would come in from Stembridge, and various film producers, seeking firearms information. I suggested to the The Long Riders (1980) prop people that one or more of the James-Younger gang use Smith & Wesson) Schofields, since they were known to have carried them. Stacy Keach’s Frank James character packs one in the film. Another time I suggested the use of the Auto Mag pistol, and connected the filmmakers with Harry Sanford, then president of the Auto Mag Corp., so they could acquire two (made from leftover parts) for Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry 1983 action thriller, Sudden Impact. I’m particularly proud of having played a small part in the Australian Western Quigley Down Under (1990), by suggesting they use the 1874 Sharps (rather than a percussion breechloading rifle, that could not produce any believable accuracy at 1,200-plus yards) and put the producers in touch with Shiloh Rifle Mfg. Co., in Big Timber, Montana. (See the full story in the April 2021 issue of True West.)

On-Set With Firearms

Sadly, a couple of tragic incidents in Hollywood led to more work in film for me. After a couple of unfortunate gun mishandling accidents that caused the death of two young popular actors, I received a call from a studio prop man who was giving a two–day seminar on firearms safety. He had his classes divided into specific genres—military, law enforcement, full auto and more. I was brought aboard to host the class on guns for the Western/Period. I did so while dressed in an Old West frock coat outfit, accompanied by my wife, Linda, who appeared in a Victorian bustled day dress, to show the many places in 19th-century garments a woman could hide weapons. After my firearms handling and safety discussion, I performed a fancy gun handling and blank shooting demonstration a la Wild Bill Hickok.

At the conclusion of the class, I was approached about working with Mel Gibson for his 1994 production of Maverick. After a successful audition with the film’s production people, including Mic Rodgers, stunt coordinator, and Gibson’s stunt double, I soon found myself in Mel’s production offices. I must say that Mel, and most of the big names I’ve worked with were a joy to be around. Mel in particular, was a quick and eager learner, whose on-screen fast and fancy gun-handling with an 1873 Colt Peacemaker proved to be an excellent calling card for me for years afterward. Also helpful was the fact that our initial one-hour session was videotaped and a few moments of my gun coaching with Mel made it to a televised “Making of Maverick” special.

Boomtime

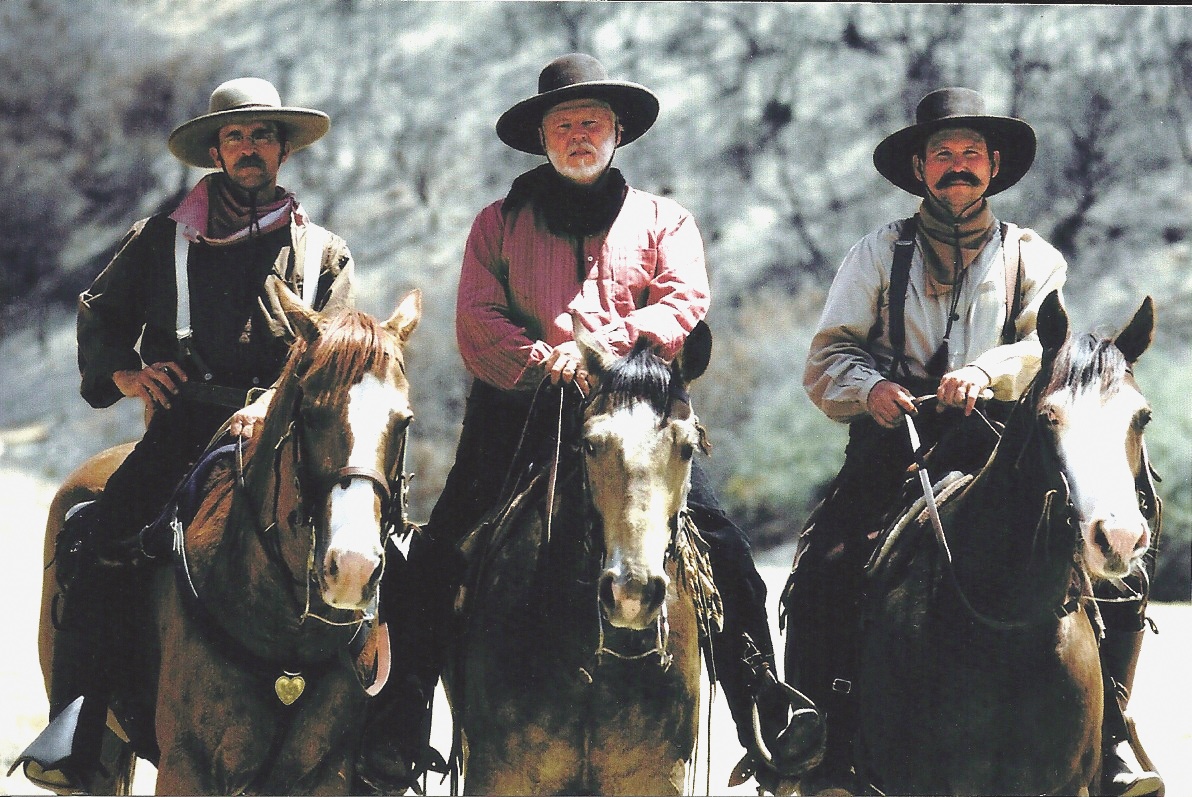

The mid-1990s was a booming time (pun intended) for Westerns, and I was kept quite busy. This latest rage with trail dust sagas brought the opportunity to work with Rob Lowe for Frank & Jesse (1994), Armand Assante’s 1994 HBO oater Blind Justice, as well as Lightning Jack with Paul “Crocodile Dundee” Hogan (1994), and with Patrick Swayze and Catherine O’Hara in that same year’s Tall Tale.

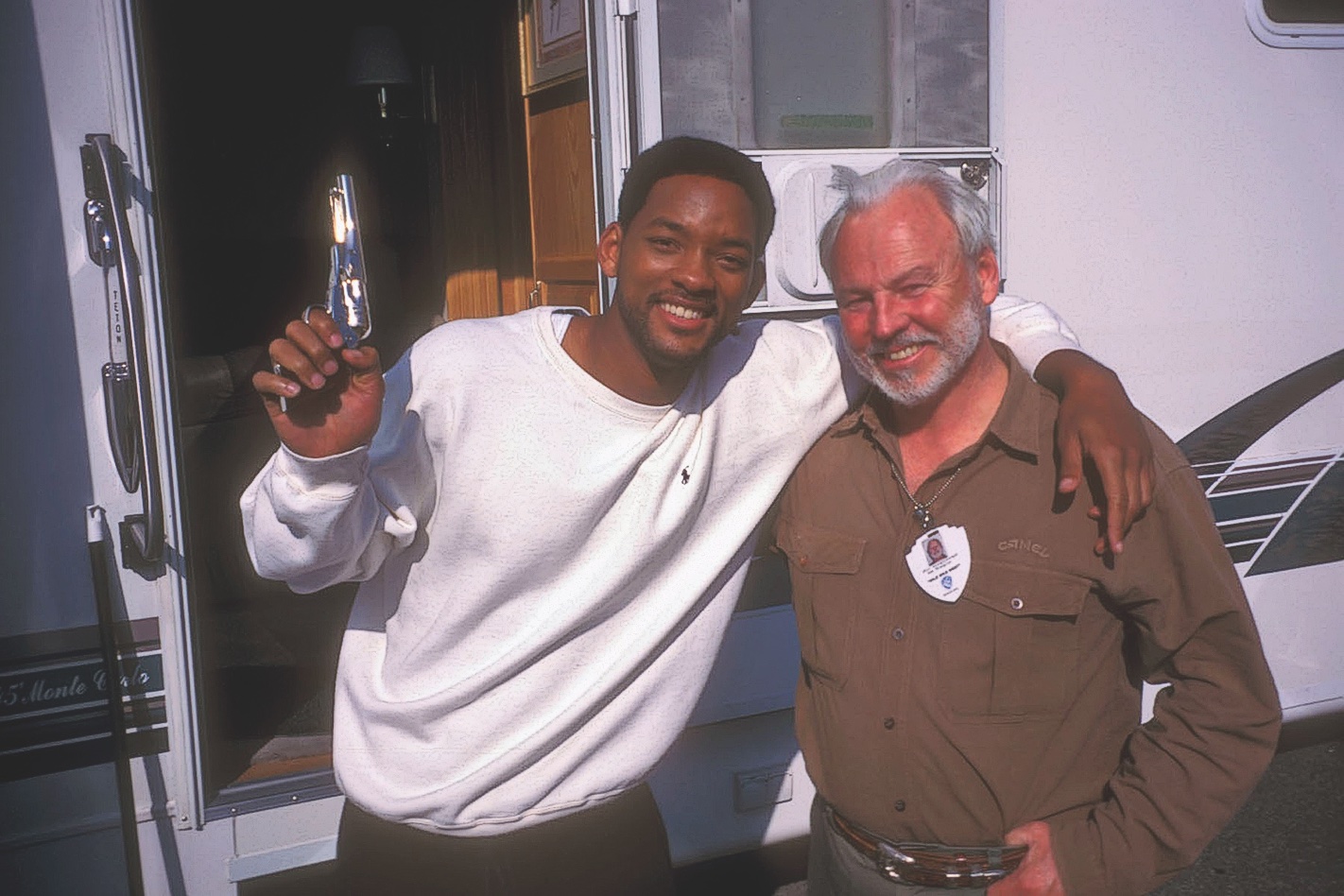

As the cowboy craze receded, film work still came my way as an on-camera “talking head” historical interviewee and/or behind the scenes as a consultant, and sometimes wrangling horses (including my own), on a host of History Channel series—the popular Tales of the Gun, Modern Marvels and others. While I was working on the cable network shows, along with hand doubling actors for trick gun scenes (including twirling a pair of power drills for a scene in TV’s Parker Lewis Can’t Lose), calls came in for more “A” pictures. Coaching Will Smith in some fancy gun work for 1999’s Wild Wild West, and a one-day flintlock-loading stint with Mel Gibson again for The Patriot (2000), produced more opportunities to add my two cents’ worth of authenticity to movies. For that Mel Gibson epic, I spent several sessions getting Heath Ledger and a 12-year-old Trevor Morgan to where Heath could load and fire a Brown Bess flintlock musket at the same rate as a British soldier of the 1770s (three shots per minute), while little Trevor, who was but a few inches taller than Miss Bess, fired his trio in 70 seconds flat!

Safety First

When training or working on set with actors, we took special care while loading and handling any gun. We wouldn’t hand the actor any loaded firearm until the moment before “action” was called and filming commenced. We instructed actors to treat any gun as loaded, never aim directly at anyone, and to point any firearm at an angle slightly off to the side of their make-believe adversary in a safe direction (camera angles can adjust to give the desired look). Firearms safety was always our utmost concern, and we’ve never had any accidents with guns.

While working on various projects, my goal was to add little bits of realism, not only in the type of guns used for the different eras in Westerns, but also gunleather, period costuming and other areas that depict the film’s timeframe more accurately. In November 2002 I was on location in South Dakota, schooling 50 of 150 cavalryman extras assigned to me in the dismounted drill and manual of arms (with trapdoor Springfield carbines), circa 1890, for the Touchstone Pictures movie, Hidalgo (released in 2004). Director Joe Johnston teased me, saying I had my own army, since I had formed all of the troopers into squads of 25 men each, for ease of management. He laughed, but said he appreciated that I had them under control and not wandering around aimlessly. Fortunately, I had friend Jim Hatzell, a technical consultant himself on many Westerns, act as second in charge, along with some military veterans who pitched in, as our “regiment” marched informally to the “front” when troopers were called for on-camera shots.

Movie Magic

Working in movies has been fun, and some of the most rewarding experiences were working with small production crews, as we did for shows like the History Channel’s highly popular Wild West Tech series, which ran for three years (2003-’05). On an independent, non-union project, one often wears many hats, and historical advice is generally appreciated by all. Having played a part in many of the episodes filmed for that series, either as a consultant, an on-camera interviewee, an actor, assistant director, wrangler, or just helping out in a number of ways, I had some of the most fun and worked on shows I am quite proud of. On these productions, I had the opportunity to work closely with my pal Al Frisch of Hollywood Guns & Props, and together we feel we definitely affected the overall look of those programs. We were able to use period-correct firearms, saddles and tack, costuming—even casting many of the character actors in those colorful shows. Eventually, we had our own stock company of players for these and other projects we were involved with, including the History Channel’s Conquerors, and Texas Rangers, the Discovery Channel’s Unsolved History, American Heroes network’s Secrets of the Arsenal, and others.

Of all the “movie magic” tricks we used to add realistic touches to a show, one bit of creativity that stands out in this Westerner’s mind was for a sequence about buffalo hunting. It was a scene where Frisch and I set up a hide hunting camp with two men skinning an animal on camera. However, because of the difficulty in obtaining a real animal carcass, we created a “dummy” critter, using a taxidermy buffalo head and shoulder mount, a tanned hide and several boxes and blankets stuffed up underneath. Once we rounded the hide off, giving it the appearance of a dead buff, it was filmed from the animal’s hide side, while the skinners worked on the stomach side with hands and skinning knives bloodied. Even from a couple of feet away, it looked like they were actually skinning a buffalo! That’s just one example of the extra effort we put forth to give a film authenticity. On any project I’ve been involved in, my goal has always been to make it look authentic. I sincerely hope the audience feels we’ve succeeded.

Phil Spangenberger is a longtime Old West historian, professional gun writer, world-traveled Wild West mounted showman, Hollywood gun coach, technical consultant and character actor. He has written for Guns & Ammo Magazine and is True West’s Firearms Editor.