The most celebrated Colorado convict was wooed and loved—despite his life sentence for eating his camping compadres.

Why do some women become infatuated with heinous serial killers and mass murderers confined in jail cells? Why, in some unusual cases, do they go so far as to open communications with these men? Mental health professionals refer to this disorder as hybristophilia. In popular culture, the ailment is referred to as Bonnie and Clyde syndrome. The condition is usually characterized by a woman who will communicate with a high-profile criminal to try and kindle a relationship with them.

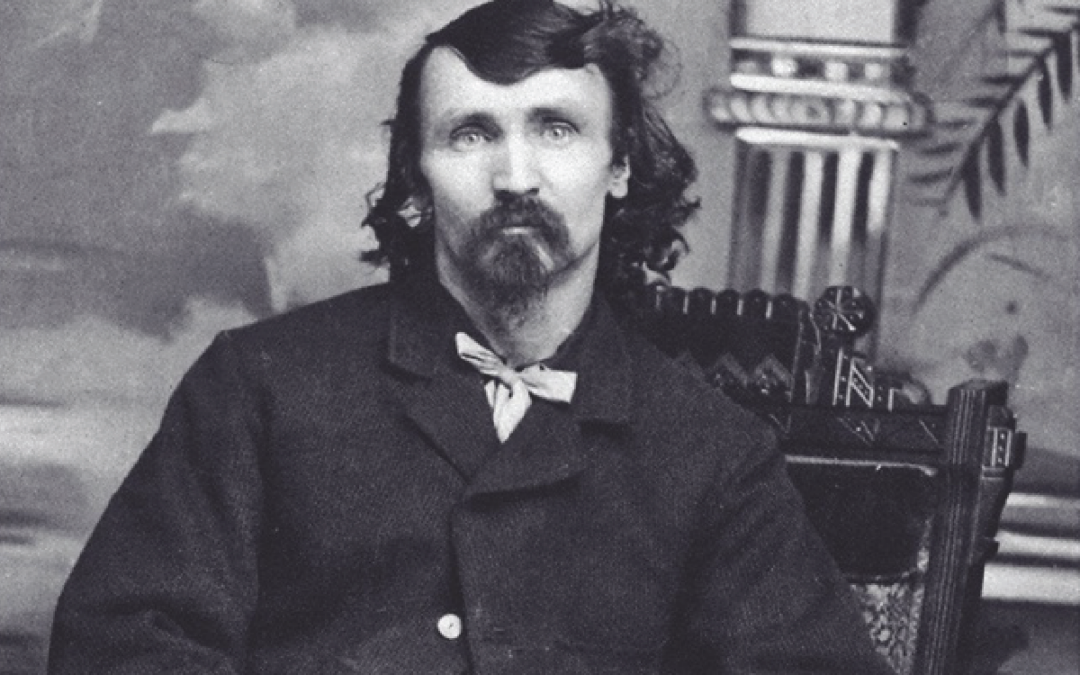

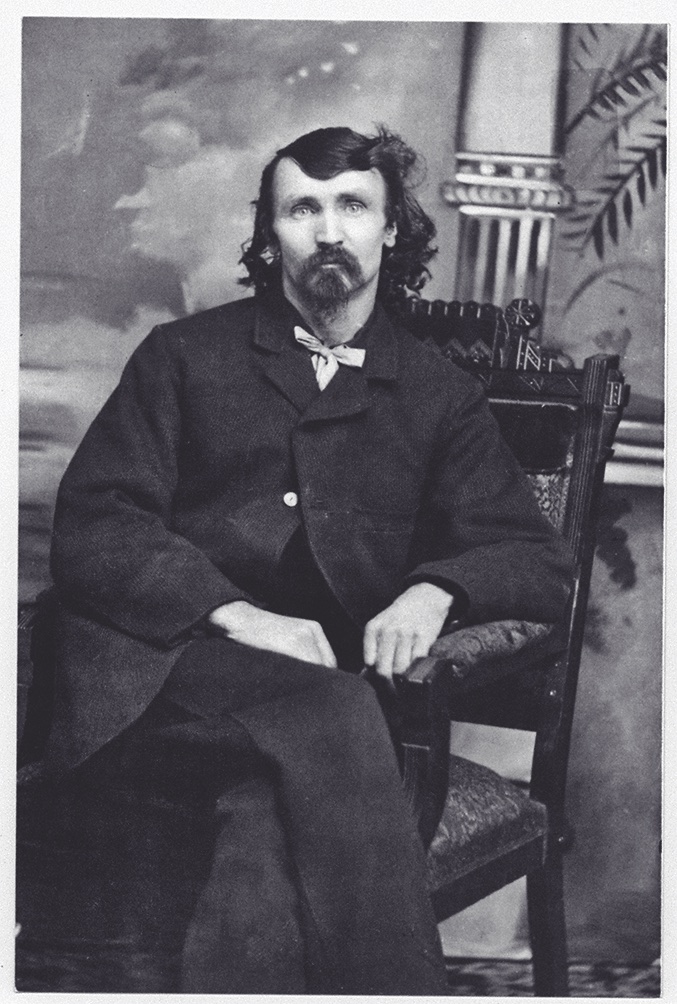

This syndrome is not solely a 20th-century phenomenon. In fact, the most notorious cannibal of the Old West, Alfred Packer (or Alferd, depending on which spelling you accept), received “fan mail” from several adoring women while he was incarcerated for his crimes.

Packer is infamous for committing cannibalism during the winter of 1874 after guiding a group of five men into Colorado Territory’s San Juan Mountains during a horrendous snowstorm. After arriving by himself at the nearby Los Pinos Indian Agency, Packer spun a story about his comrades having left him while they searched for food. He stuck to this tale, saying he was unaware of what happened to his companions, even though he carried large sums of their money and possessed a rifle known to have belonged to one of the men.

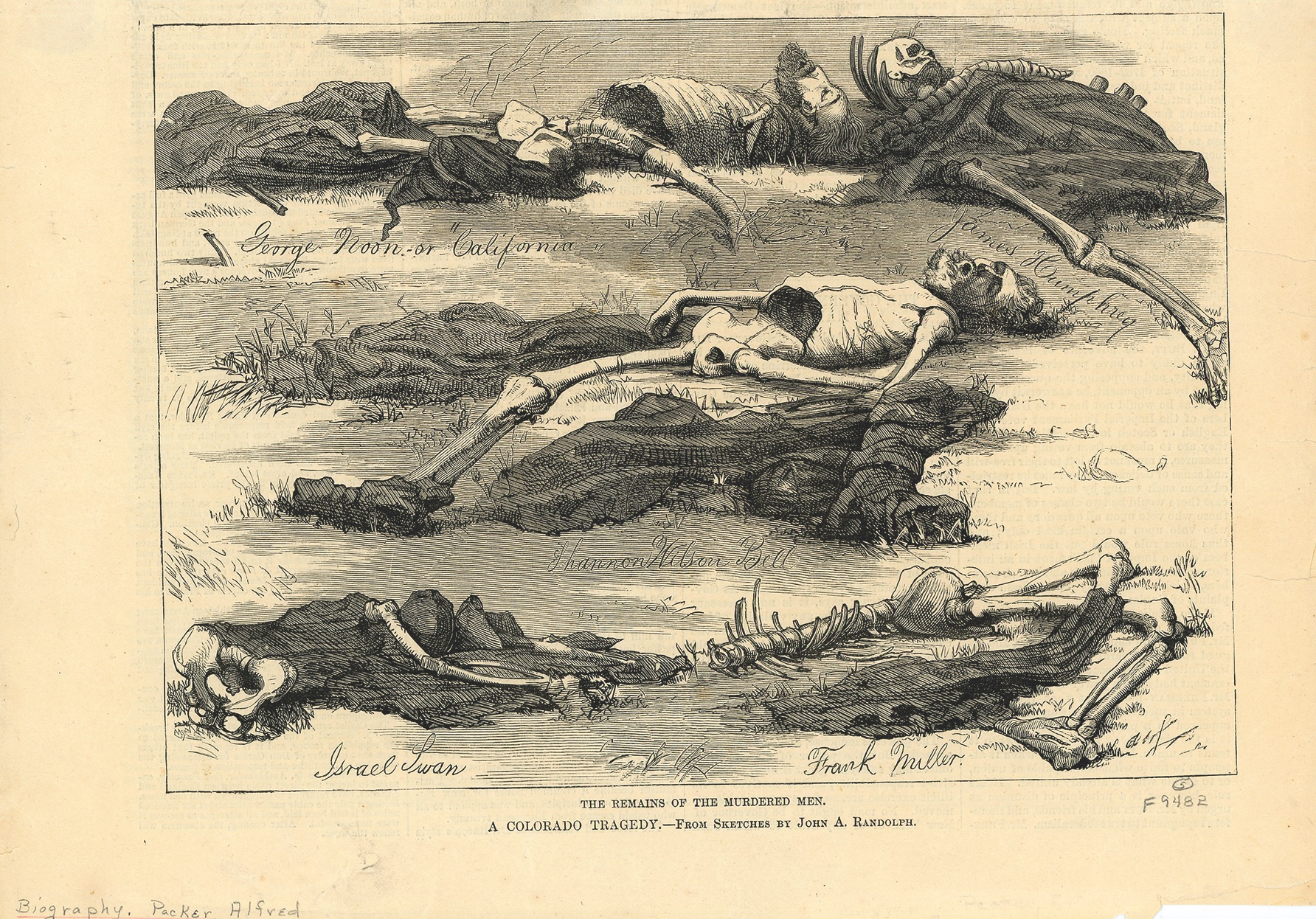

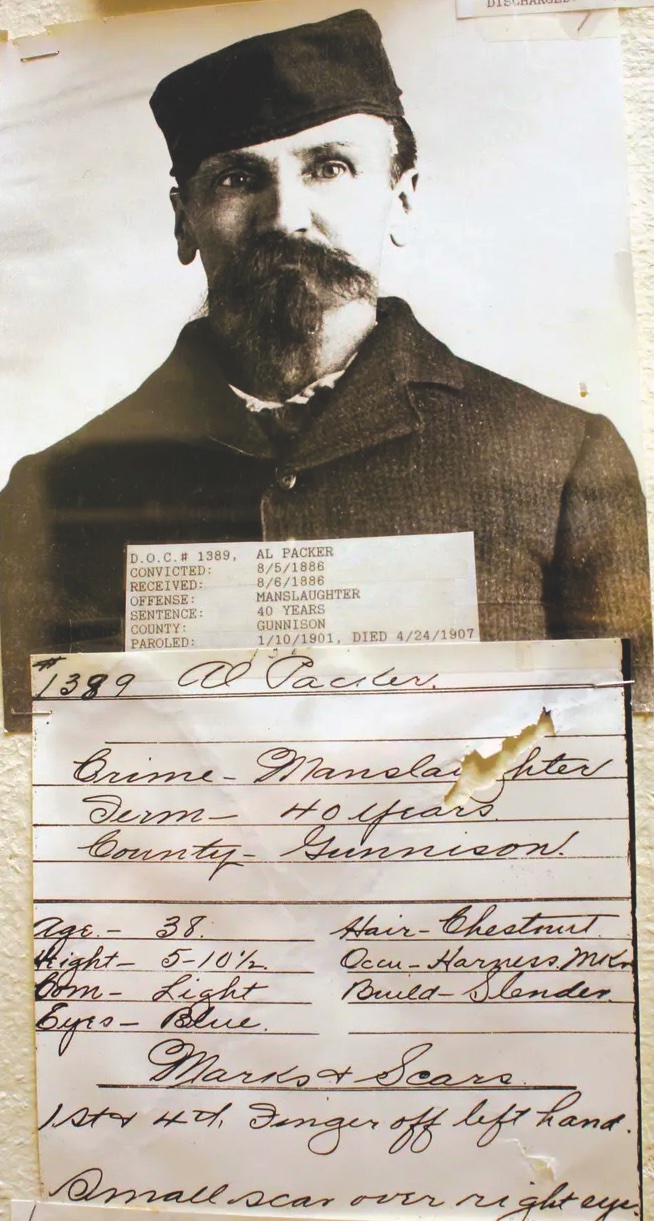

Packer’s flimsy account was questioned by those who knew him, and he was soon arrested. Under interrogation, he admitted to partaking in cannibalism. However, he denied committing murder. Following Alfred’s incarceration, the mutilated bodies of his five companions were discovered, and most historians conclude that the remains were found near the Gunnison River by an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, who was on assignment in the area. The corpses showed signs of intense violence with fractures of the skulls consistent with blows delivered by a hatchet. Following this discovery, Packer escaped from jail and went on the lam for nearly 10 years until March 1883, when he was discovered in Douglas, Wyoming, living under the alias “John Swartze.”

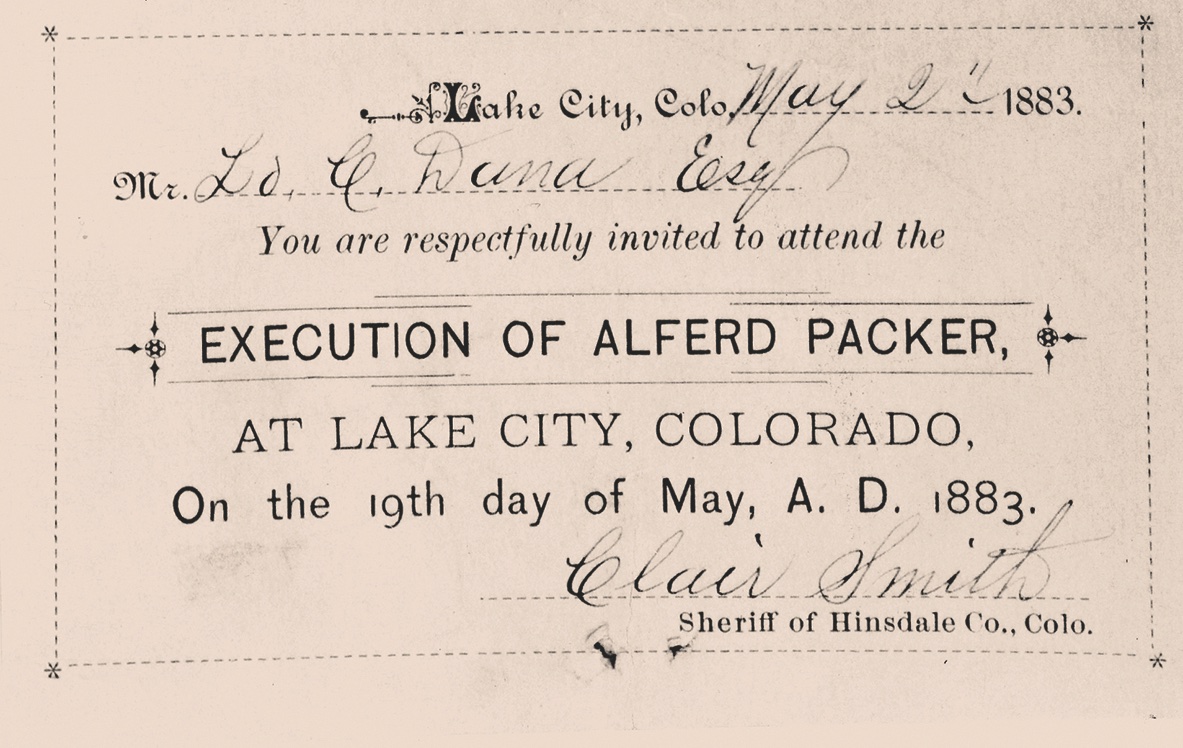

After this arrest, Packer was put on trial, convicted of murder, and sentenced to death for killing “some [five] other persons for their money and a vicious desire for human flesh and blood.” During sentencing the judge famously uttered the words, “I sentence you, Alfred Packer, to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, dead, dead.” However, Alfred would escape death on a technicality and receive a second trial. At the outcome of that trial, Packer was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to a 40-year prison term in the Colorado State Penitentiary in Cañon City. Throughout his incarceration, Packer maintained his innocence, saying he only acted in self-defense when attacked.

Perhaps the most prominent woman to champion Packer’s cause while he was in prison was the popular journalist known by the pen name “Polly Pry.” Supposedly, Polly, whose real name was Leonel Campbell Ross O’Bryan, received her nickname from fellow reporters because they said she had the ability to “pry” information out of anyone. Pry first met Packer and interviewed him while researching an article about Colorado’s prison system, focusing on the Colorado State Penitentiary.

Polly, who was also the first female reporter for the Denver Post, believed Packer to be innocent of murder. She used her column to argue that “since sailors were legally allowed to eat people if they were lost at sea, the same rules should apply to people stranded in the mountains.” Through the popularity of her Packer column that brought increased revenue and readership, Polly persuaded the owner of the Post, Harry Tammen, to pay for Packer’s defense and demand a retrial. The retrial eventually led to a pardon for Packer on January 7, 1901.

But before Polly Pry helped secure his eventual release, Packer received “a constant stream of the curious” who came to ogle “Colorado’s Nationally Known Prisoner.”

Along with the influx of onlookers coming to his prison cell, Packer began receiving loads of letters from adoring well-wishers. One of these sympathizers was Mrs. Rebecca A. Newman. Born in 1846 in Herkimer, New York, Newman worked as a schoolteacher while residing in the Bronx neighborhood of New York City. By opening communications with Packer, she apparently hoped to form a friendship with him and express her sympathy for his circumstances.

When Colorado’s Governor-Elect Alva Adams learned of Newman’s affections he warned her, writing, “If you knew Packer—knew his career and was acquainted with all of the details and surroundings of his horrible crime that you would not care to be his defender and to offer excuses for his conduct.” Not dissuaded by Adams’ alarm, Newman insisted communications be opened anyway. In 1887, he relented and forwarded her letter to the State Penitentiary.

Disturbingly, Rebecca implored Packer to delve deeply into his crimes and give, “a full detailed statement of the whole circumstances connected with [your] most extraordinary trials and sufferings.” Alfred, unsurprisingly, was willing to comply. Detailing his account to Newman, Packer stuck to his story of self-defense and only committing cannibalism for survival. However, he did divulge several interesting details about his ordeal.

Before the deaths of his five companions, in November of 1873, Packer lied to those men and 15 other miners near Bingham Canyon, Utah Territory, telling them he had the ability to guide them to Colorado Territory’s rich precious metal region. Because of his ineptitude, Packer caused the men to slog through the San Juan Mountains for nearly two months, only covering 250 miles at a meager average of three miles a day.

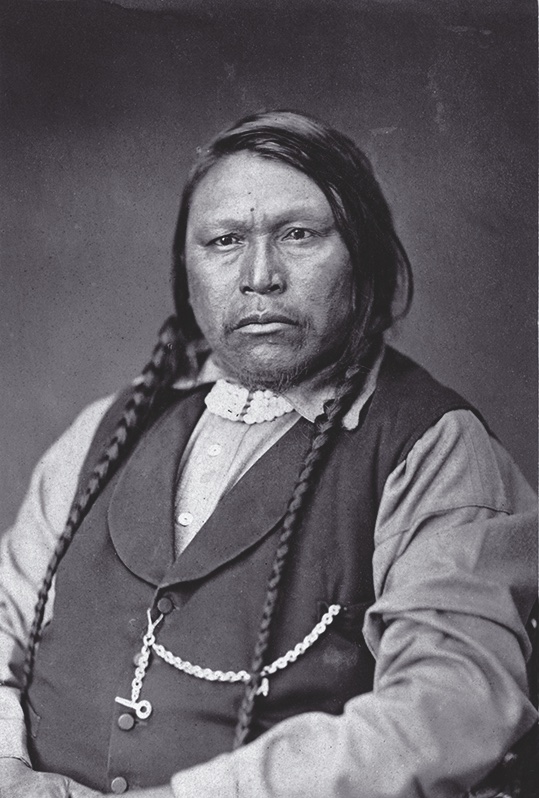

After wandering in the wilderness, the beleaguered party were eventually discovered by warpainted Ute Indians. Among the Ute braves was Chief Ouray, who took them to a spot near his village where they set up a makeshift camp. Known as “The White Man’s Friend,” Ouray exchanged food and supplies with the travelers while advising them to shelter at their encampment until the winter passed.

However, a contingent of five men—George Noon, Shannon Wilson Bell, James Humphrey, Frank Miller and the elderly Israel Swan—wanted to reach Breckenridge before thousands of fortune hunters descended on the area. These men would be the five who, on February 9, 1874, foolishly followed Packer into the maw of a ferocious storm. The hope of this contingent was to reach the Los Pinos Indian Agency, the closest outpost to Ouray’s camp, and from there head to Breckenridge.

Addressing these events in his correspondence, Packer attempted to deflect blame for leading his comrades to their doom by throwing Ouray under the wagon’s wheels. He wrote, “From conversations with the Indian Chief, the noted Ouray, we learned that in his opinion we could reach the Los Pinos Agency in not over 5 days on foot across the mountains. I had never been at the Agency and was only guided by general reputation and information rec’d from Ouray.”

Packer was a known pathological liar, and the account he gave to Newman concerning Ouray is not entirely truthful. Ouray never told Packer that they were only five days from the Los Pinos Agency because there was at least three to four feet of snow blocking their path. In fact, the prospectors who remained at the camp stated, “[Ouray] told them…they would all die, and that he had not an Indian in the band that would go to show the route…as they were afraid of the deep snow.”

However, when Ouray realized Packer’s party was still going to stupidly stagger into the storm, he graciously provided them with provisions. Alfred wrote that they were given, “scanty fare… about 20 lbs of flour and not over 10 lbs of good meat.” Ouray also drew a crude map on the ground with a stick giving them, “all the directions he could as a route.” Somehow, these men still did not grasp the desperation of their circumstances and trudged on.

Not surprisingly, Packer told Newman, “At the end of 9 days the last provisions had been eaten. We ate our goatskin moccasins and subsisted on rosebuds until we were weakened and emaciated and mentally completely distracted.” Those conditions clearly led to the deaths and cannibalization of all in Packer’s party.

Alfred also attempted to downplay going on the run for a decade, telling Newman, “I was not arrested or even censured by any one until 1883 when I was arrested. Though I was in the country and seen by all men during all the time.” This is also a ridiculous statement considering Packer was living in a different territory and under an alias for the very reason of evading capture.

While in prison, Packer often crafted leather belts, bridles, wooden canes and watch fobs fashioned from dyed and braided horsehair. He normally sold these items as souvenirs to the gaping gawkers visiting him. However, he would occasionally gift one of these items to people he thought were special. He gave a chain bracelet to Rebecca as a sign of his affection and desire for a relationship. Like most manipulative criminals, however, Alfred clearly had hidden intent. Through his correspondence with Newman, he hoped to find out what she could do for him. Packer wrote, “[I will make] you proof I am worthy of the aid of the philanthropic and those better situated than I am financially and otherwise.”

Newman died in 1926 at the age of 80. Packer died alone in 1907 in Littleton, Colorado, a suburb of Denver at the age of 69. Whether Newman and Packer ever met is lost to history, but women like Newman still exist today. They play a dangerous game when contacting famous criminals who are experienced manipulators. And, for those who do not proceed with caution, sometimes end up being eaten alive.

Courtesy Denver Public Library Special Collections, C Photo Collection 516

Kellen Cutsforth is a ghostwriter and author who has published numerous books and articles on the American West. His titles include Buffalo Bill, Boozers, Brothels and Bare-Knuckle Brawlers, the co-authored Old West Showdown, and its sequel Standoff and High Noon.