Was he Alaska’s greatest backwoodsman and trailblazer?

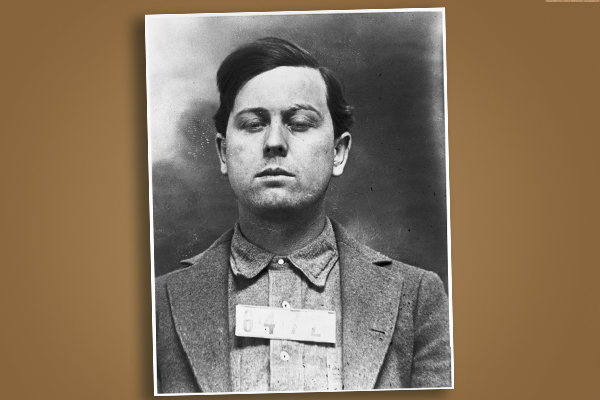

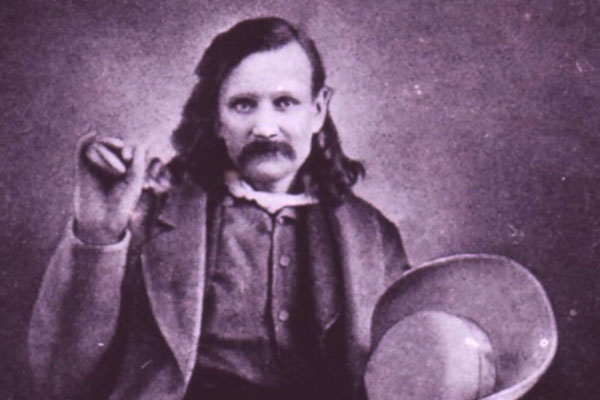

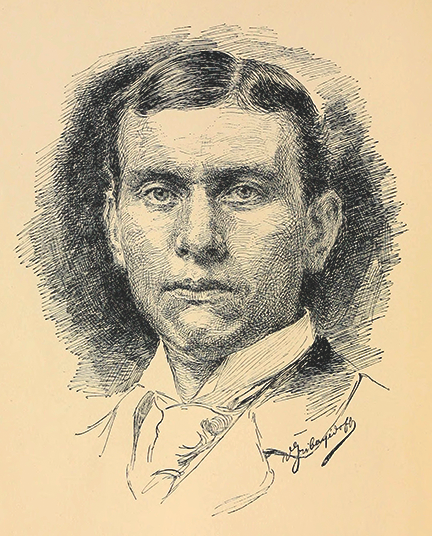

A Haines woman who’d known John “Jack” Dalton as a frequent guest at her girlhood home described him as “a dapper, well dressed, ladies’ man” even at 50. Others dismissed him as a scoundrel. His achievements, however, were undisputed. Skagway’s paper, The Daily Alaskan, lauded him as “perhaps the most famous pathfinder” in the Territory. In an 1898 photo, he looks like a good man to have on your side.

Small of stature, with broad shoulders somewhat out of proportion to the rest of his body, Dalton, unrelated to the notorious Dalton brothers, yet a marksman nevertheless, normally went about armed. The Van Dyke beard and thoroughly parted hair added a pinch of respectability to a brawler’s round face with high cheekbones and a flat-bridged nose. A fireman aboard a Yukon River sternwheeler deemed him preeminently fit, a square shooter in business, and agreeable, “but a bad hombre to cross or run up against.” Dalton thought nothing of snowshoeing 50 miles to a cache in one day, admitting to an appetite afterward. Despite his size, he cut an imposing figure in a black, wide-brimmed hat, suspenders, calf-high moose-skin moccasins, and sporting a Colt holstered high on his hip—in a working stiff’s, not a gunslinger’s, way of packing heat. He cleaned up nicely, donning a suit and loosely knotted necktie.

His zest for roughing it kept him spry long after his Alaska days. The early 1920s found him prospecting for diamonds in British Guyana. He lived moderately wealthy to be 89, and his longtime physician’s impression in 1929 would have made a great epitaph: when Dalton was nearing 75, he looked 55, and, if provoked, flared up like the 25-year-old firebrand he’d once been.

The Great Northwoods to the Alaskan Frontier

Details of Dalton’s early career are hazy and sometimes contradicting. Probably born in Michigan in July 1856, Jack got little formal schooling. Self-taught, he was rather well read and well spoken. Some scrape during his teenage years might have caused him to light out for Oklahoma. He cowboyed for the Hadley Ranch in Baker, Oregon, before moving to Burns, where he ran a small logging outfit. In 1883 he sailed north on a sealer.

Already an expert wrangler, hunter and cook, Dalton became fluent in Chinook, the trade jargon that entwined the Pacific Northwest. His English travel companion, Edward Glave, an associate of the African explorer Henry M. Stanley (who located Livingston in Tanzania), considered Dalton one of the two best men he ever saw handle a paddle. Spending two years total with the scout, he likened his route-finding abilities to “the talent of a gifted musician, who hears a new piece only once, and then repeats the whole without difficulty, note for note.” In 1886, these skills earned Dalton a place as roustabout and camp cook on a New York Times-backed expedition to climb 18,000-foot-high Mount Saint Elias astride the Yukon-Alaska border, the second highest peak in the U.S. and Canada. Struggling with fast, silt-laden rivers and through Tyndall Glacier’s crevasse field, hampered by an ill, corpulent leader, the men had to backtrack.

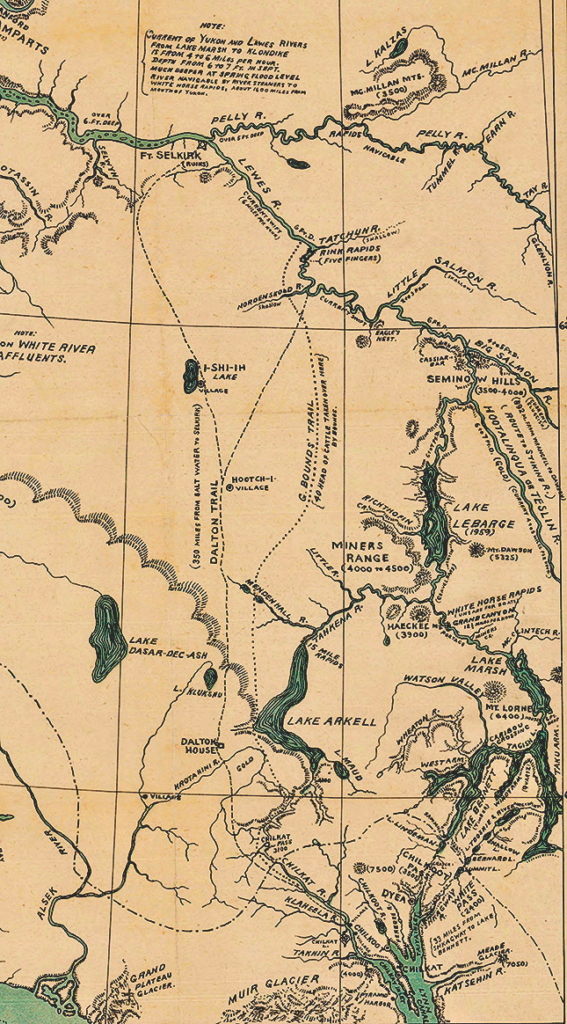

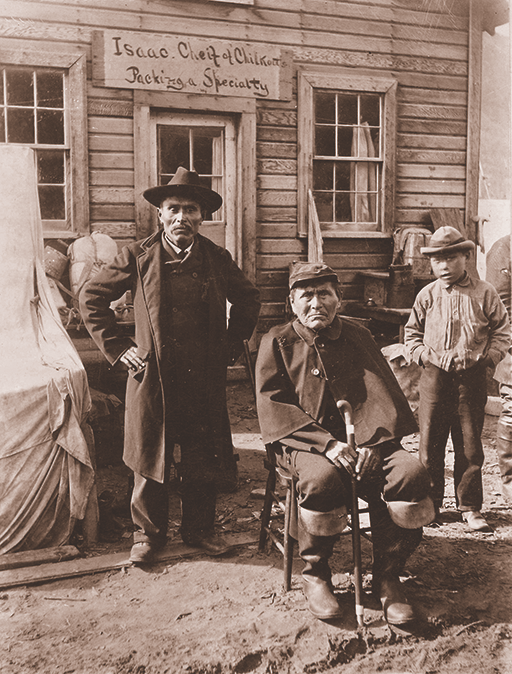

In 1890, Dalton joined a party to chart Southeast Alaska’s boondocks funded by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. His practical and parleying finesse cleared passage on one of several ancient paths inland called the “Grease Trails.” The coast’s Chilkats, a Tlingit Indian band, controlled this particular access. Two other bands ruled the Chilkoot and White Pass corridors respectively. The trail network’s name referenced oil rendered from tiny eulachon “candlefish,” a commodity the Chilkats bartered for furs, hides and copper nuggets from upcountry Athabaskan tribes. Decades before, Chilkats raiding the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s upper-Yukon post, Fort Selkirk, had exiled its factors for the next 80 years.

After paying a hefty toll to chief Kohklux (who’d fortified his clan house with two canons from a Russian shipwreck), the six White men sponsored by Frank Leslie probed the headwaters of their Chilkat porters’ home river. They traversed ravines, icy creeks, crusty snowfields and the “cheerless” heading glacier before descending the pass to Kusawa Lake. There, Dalton and the expedition’s executive officer, Edward Glave, parted ways with the others to loop back to the gulf. Dalton schlepped three pairs of snowshoes, a gold pan, a bread pan and four saucepans belted around his waist, besides a rifle, revolver and ammunition. Glave, an artist and journalist—lugging one big kettle, teapot, blankets, a sack of books, camera, overcoat and one wild duck—commented on their clanging, which “might have aptly served as the heralding strains of the Salvation Army.” At one point, perhaps simply because he could, Dalton piggybacked Glave and his burden to ford a stream: Christopher with a hogleg, patron saint of bush travelers. Glave, whom fever killed in the Congo, remembered him as “a most desirable partner, having excellent judgment, cool and deliberate in time of danger, [who] possessed great tact in dealing with the Indians.”

The two secured a canoe and the services of a shaman as guide on the rowdy Alsek that split the Coastal Range. It spat them out in Dry Bay soaked through and sore.

Hauling Horses and Hauling Ass

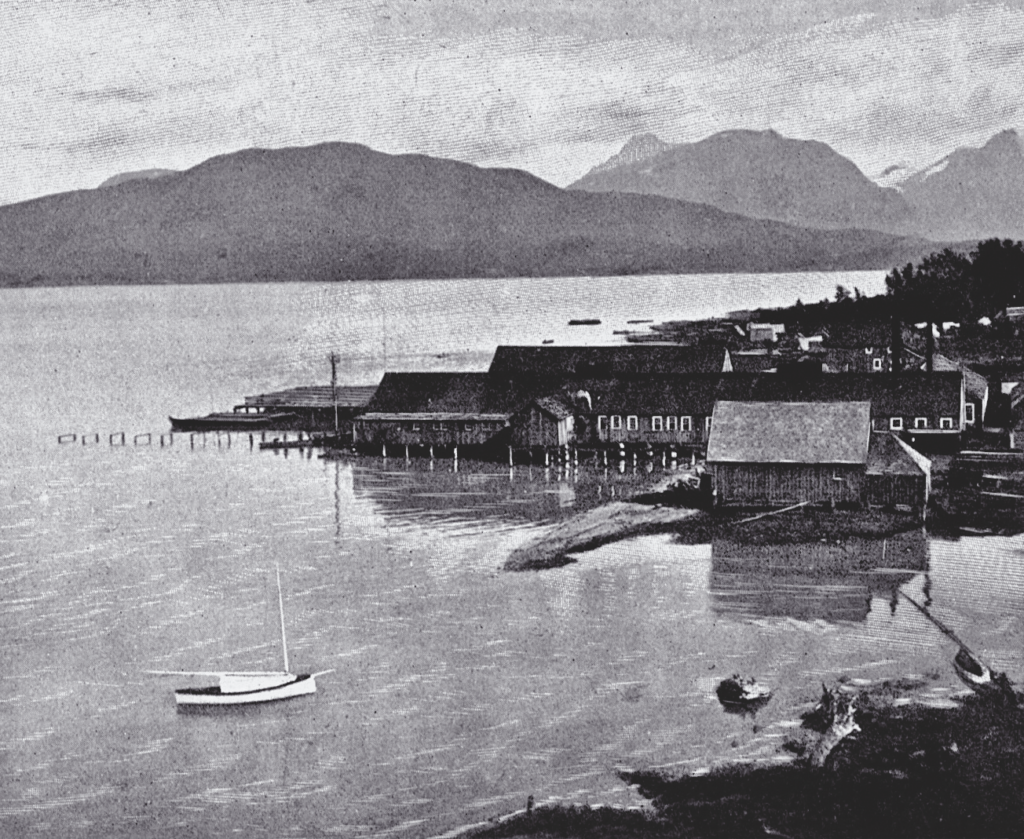

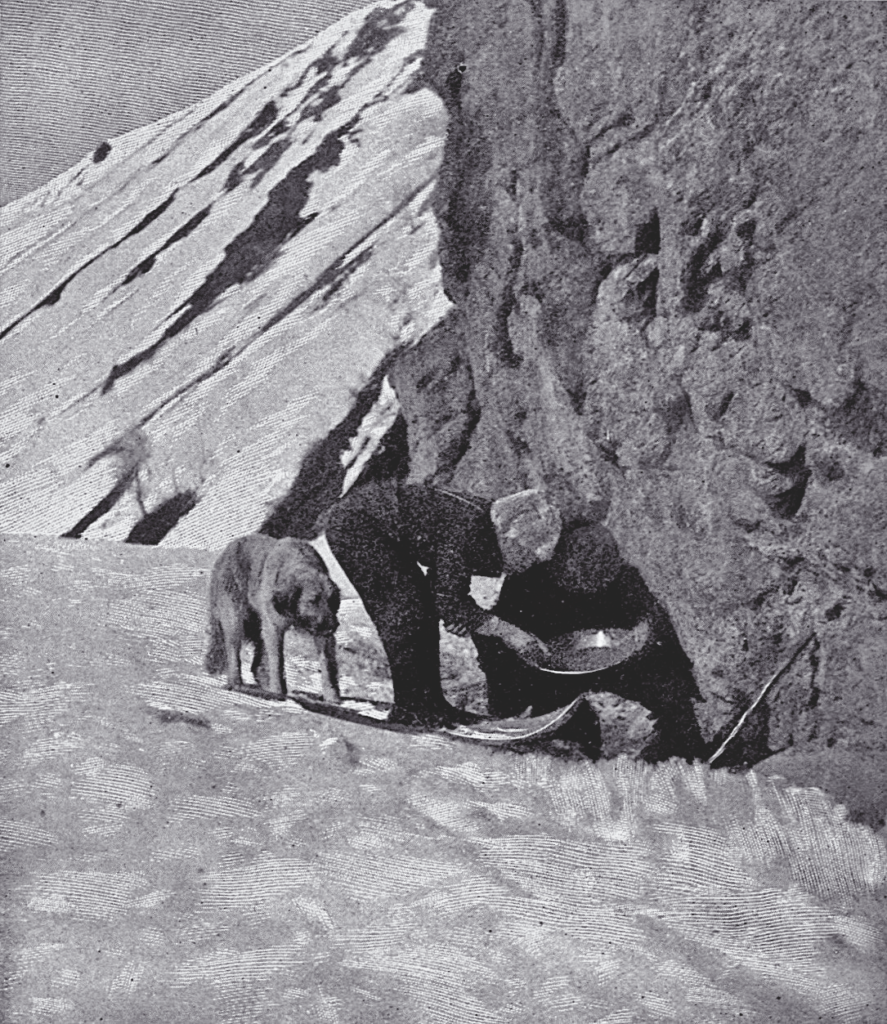

Regrouping in the spring of 1891, realizing the potential for a byway of their own, the partners adopted a freighting method unseen in the north. They pastured four “short, chunky” packhorses bought in Seattle and landed at Lynn Canal’s Pyramid Harbor, near present-day Haines, Alaska. Wanting to keep this trek to the interior low profile, they hired just two Chilkat guides and an interpreter. No horses had ever been in that country—the Indians and miners doubted their worth in such rough, steep terrain. Before Dalton introduced pack stock, Native trade parties—snowshoeing in winter—could take more than a month, with up to 100 men each carrying 100 pounds or more.

Dalton, expecting deep, soft snows at the 4,750-foot summit, cobbled together four sets of horse snowshoes from spruce-sapling loops webbed with plaited rope that resembled oversized lawn-tennis rackets. The horses at first did not value these trappings. Snorting and trembling, they reared up, savagely flailing, and flopping like stranded salmon, trying to shake the things off. Somewhere on their journey, a snow bridge collapsed, and a horse plunged into a stream coursing underneath. In the lowlands, their mounts floundered up to the saddle blankets in morass, but the riders, unloading, unsaddling and pulling on lead ropes, saved them. The mosquitoes were so thick that the men sometimes couldn’t discern the horses’ outlines. At camp, Dalton hobbled the string, lest bugs stam-pede it for a hundred miles. Those nags soldiering on under 250-pound packs in subzero temperatures impressed Indians used to crawling on hands and knees up treacherous pitches with their wares while strapped into tump-lines; they soon paid Dalton for hauling goods into the Yukon River watershed. Challenge came air-borne also. Exploring Kluane Lake in an Indian cottonwood dugout with oars and a jury-rigged sail, Dalton and Glave almost drowned, hypothermic and dashed against cliffs, when a freak storm capsized their boat. They lost irreplaceable gear, Dalton’s pocket watch, a compass and sextant, rifles, ammo and cooking utensils.

Dalton spent most of 1892 and 1893 scouting a better packhorse trail from Pyramid Harbor. Felling timber, corduroying marshy spots with logs cut short, and building bridges, he smoothed out the trail that would bear his name. Roads to the claims often were poorly maintained, arduous and risky. Streams had to be crossed and recrossed dozens of times. Ice banks girdling them meant wagons teetered several feet to a trough’s bottom where currents endangered men and beasts. Snowmelt on hot days swelled rivers; quicksand posed further obstacles.

Dan McGinnis, a store clerk in Haines, accused Dalton of trying to monopolize trade in the region, which on March 6, 1893, led to a showdown. McGinnis had told some Chilkats about Dalton’s planned trail and post in the southwestern Yukon that would siphon off their profits. During a struggle for Dalton’s revolver at Murray’s cannery store, a shot wounded the clerk, who died on the way to the Juneau hospital. According to sworn court testimony from the sole eyewitness, Dalton had confronted the seated McGinnis and called him a liar before pistol-whipping him. The fourth blow triggered a shot that tore into McGinnis’s shoulder. With the final blow, Dalton’s weapon again discharged, putting a fatal slug in the clerk’s gut. Dalton, initially jailed in Juneau, was acquitted to the dissatisfaction of citizens who asked him to leave Alaska or face consequences. A lynch mob was swayed into granting him three days to skedaddle back onto his Yukon turf.

Three Houses and a Graveyard

That terrain, familiar by now, ranged from mosquito-riddled swamps to a “good hard road covered with reindeer moss.” The trail he’d blazed by chopping bark from trees as bright beacons culminated after 1,700 feet of switchbacks gaining a pass, the only steep part. At Glacier Camp, 30 miles past the summit, a panorama of 26 ice floes greeted the weary. His trails were well suited for horses, cattle and sheep, easier yet longer than the alternate routes over the Chilkoot and White Pass trails, but Dalton’s dream realized never drew comparable numbers.

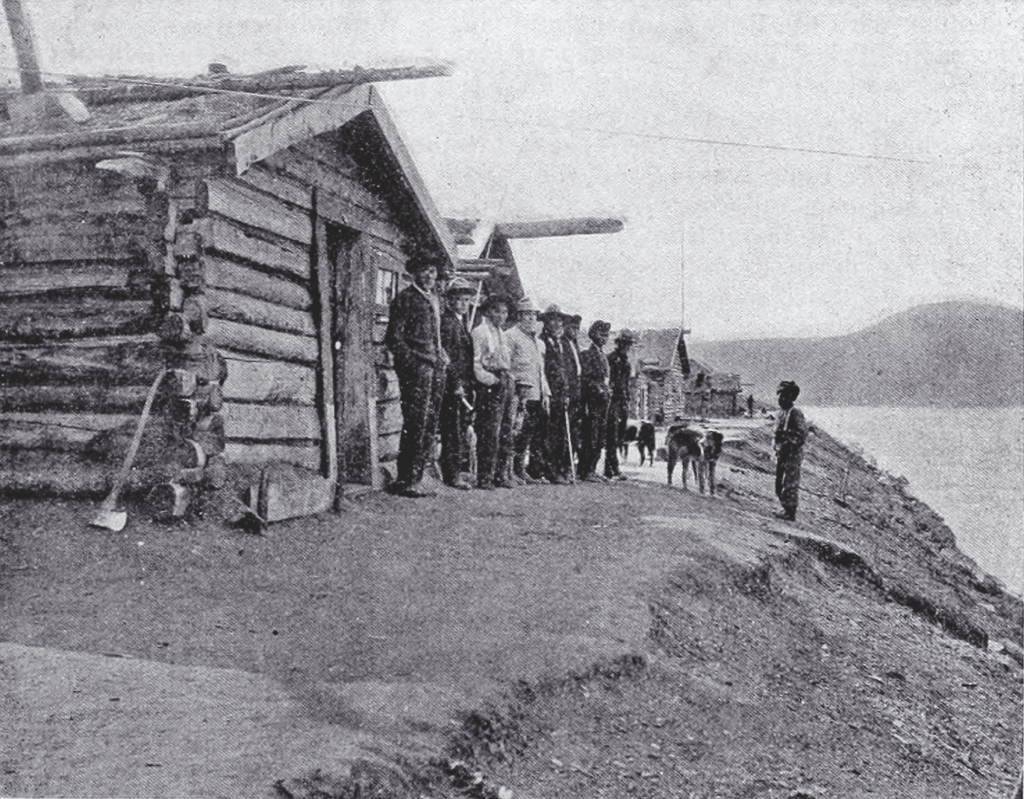

Living with a common-law Native wife, the bad hombre in 1895 established Dalton’s Post near Neska-ta-heen—“three houses and a graveyard”—at an Alsek River crossing. He exchanged blankets, guns, powder, flour, knives, axes, matches, kettles and tobacco for mink, marten, bear, otter, beaver and fox pelts his wife’s people trapped.

Horses proved to be hardy enough to winter at that elevation. The Natives, marveling at the snorting, antlerless creatures, feared them. A surveyor Dalton hired fixed the approximate border, the grandiloquently named Dalton Trail International Boundary Line, beyond the summit. A North West Mounted Police detachment at Neska-ta-heen curbed smuggling and protected Klondikers. One ’98er reported Dalton’s Post shelves “piled high with calicoes, and ginghams, shoes, hats, tin pans, plates, and cups, while from the roof-beams depended kettles, pails, steel traps, guns and snowshoes.” In 1898, with the owner gone guiding, members of Soapy Smith’s Skagway gang supposedly robbed several thousand dollars there, but their operating in Canada is unverified.

In 1894, Dalton had leased a parcel of land and a warehouse at Haines Mission to trade with local Tlingits. Working with the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Co., he also improved commercial freight “bobsleds” billed to withstand “rough hard usage over the almost impassable Alaska trails.” His summit trail fully functioned when Klon-dike fever broke out in 1897. About 2,000 beeves for feeding the miners tramped it the following summer. Even reindeer were herded up that subarctic Silk Road. A presumed food shortage in the previous winter had prompted the U.S. government to finance a relief effort. Five hundred Norwegian reindeer left Haines, though most starved to death before reaching the alpine zone’s lichens. A mere 114 trotted into Circle City nearly a year later, in January 1899.

Courtesy Hathi Trust

Pioneer Grit

From that year on, with the Secre-tary of the Interior’s approval, Dalton charged stampeders dearly for the right to use his highway to riches on the American side—$2.50 per head of cattle, horse, mule or burro, the daily wage of a brewer or baker, collected at a toll tent three hours from Lynn Canal. Goats, sheep and swine brought 50 cents each and walkers $1. Merchandise was one cent a pound. The government decreed that Chilkats got to commute for free. At Rink Rapid or Fort Selkirk, endpoints of a fork in Dalton’s trail, livestock boarded scows or timber rafts, which whisked it downstream to Dawson. Pack trains numbered up to 250 horses, and oxen pulled winter sled loads. McClure’s Magazine advised tenderfoot “cheechakos” not set out before May 15, because of the lack of forage in the high country before then, and to each take a saddle horse and a few packhorses. A Dalton sideline, the Pony Express Co., conveyed passengers (and once, mail) from steamers anchored in Pyramid Harbor to those plying the Yukon River below Rink Rapid, which made for a 10- to-12-day trip between Southeast Alaska’s Panhandle and Dawson. Keeping horses at both ends and personally guiding some parties, Dalton charged $150 for the Haines-to-Rink Rapid leg or the reverse.

Spring transformed many Klondike approaches into hoof-churned sludge. “When the roads are in a mire, then the freighters earn their hire,” a drovers’ song went. They slathered pitch or bacon fat around the ears and eyes of pack animals plagued by “a hideous assortment of teasing insects.” When freighters’ bitten heads got too lumpy to fit into hats, men smeared these ointments on themselves.

Dalton jealously guarded his brainchild against trespassers. He shadowed one group wanting to skip the toll while it wandered through bogs and underbrush and lost most of its stock. His trace stayed competitive until The White Pass & Yukon Route railway was finished in 1900 but still attracted some business in the decade after.

Highways of History

Further inviting progress, in 1905 Dalton reconnoitered a railroad right-of-way from the central Gulf of Alaska port Cordova up the Copper River. He pummeled a foreman who’d supplied Dalton’s employees with liquor there and a government agent who refused to sign the payroll for men Dalton supervised.

The pugnacious pathfinder managed a hotel in Haines before leaving Alaska forever in 1919. He kept a shotgun loaded with rock salt under the bar of his saloon for unruly patrons. Perhaps owing to his reputation, many challenged him. The Chilkat chief Cutewait (“Indian Jim”), afraid of losing his edge on trade, tried to sabotage Dalton’s trail venture. Taking a potshot, he nicked one of his target’s fingers. Another tough threatened to open a bar next door to one of Dalton’s establishments, but the proprietor told him off with his fists.

Courtesy Library of Congress

A trailblazing gene marked one of Dalton’s progeny too. Today’s 414-mile, gravel umbilicus linking Fairbanks and Prudhoe Bay’s Arctic oilfields was named after his second son, James W. Dalton. A University of Alaska graduate serving with the Naval Construction Battalions (CBs or “Seabees”) in the Pacific Theater, James helped engineer the Distant Early Warning Line during the Cold War and worked as a consultant for the North Slope’s Naval Petroleum Reserve.

While James fought Japan, the Haines Cutoff stretch of his father’s trail revived as the Haines Highway, connected tidewater with Haines Junction in the Yukon, on the strategic Alaska-Canada or ALCAN Highway. The rest of the original 350-mile track to Fort Selkirk lies overgrown or has been erased by logging roads or rivers’ channel-switching. Still, the Klondike’s only trail built largely by one man and as a toll road, remains a token scar, a sign of pioneer grit , on North America’s final frontier.