— All Photos Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Stated —

The year 1876 proved the turning point in Calamity Jane Canary’s career. It began with two quick trips to the Black Hills with Gen. George Crook and his army in the winter and spring of that year. Calamity may have served informally as a scout (so a good source claims), but primarily she was a camp follower, hitching rides with soldiers and sneaking in among the teamsters and bullwhackers until she was discovered, chased out and sent back south. Several travelers on these trips and other observers reported her with Crook—and not always traditionally dressed or sober. One teamster described her as “dressed in buckskin suit with two Colts six shooters on a belt.” To him, she was one of the roughest persons he had ever seen. Calamity’s travel itinerary in the late spring and early summer of 1876 was chockablock, and more. In March she was with Crook to the north, in May back in Cheyenne, where she was arrested for stealing clothes, but was declared “Not. Guilty” [sic]. In early June she zipped back north for a second jaunt with Crook. Heading out of Cheyenne, “greatly” rejoicing “over her release from durance vile” [jail], she “borrowed” a horse and buggy. After overindulging in “frequent and liberal potations” of “bug juice,” she headed for Fort Laramie, 90 miles up from Cheyenne. By mid-June, Calamity was celebrating with soldiers from Fort Laramie. The rhythm of her life, already in uncertain high gear, whirled into overdrive in the coming months.

At the end of June, an encounter took place that would forever change Calamity’s story. In spring 1876, Wild Bill Hickok, newly married to circus owner Agnes Lake, and his partner Charlie (also Charley) Utter were in Cheyenne, making plans to ride north. Hickok would try his hand at mining, he promised his new wife, who stayed in Cincinnati. Charlie hoped to establish a stage line into the Black Hills. Soon after mid-June they were on their way. When the Hickok-Utter train stopped just north of Fort Laramie, the officer of the day at the fort asked them to take along several prostitutes, to keep them away from the soldiers. Calamity may have been among these prostitutes. One credible source describes her as drunk and “near naked.” Here in late June, in northeast Wyoming, Calamity met Wild Bill for the first time. They would know one another as acquaintances, and no more, for about the next five weeks. Members of the train gave Calamity a suit of buckskins for their trip into the Hills.

Contemporaries made much of the dramatic entrance of Wild Bill, Calamity and other members of the train into Deadwood in early July, picturing them as prancing along the entire main street, greeting friends. But in the weeks to come Wild Bill and Calamity were rarely together. Then tragedy struck on August 2, when Jack McCall, a drifting ne’er-do-well, sneaked up behind Hickok while he was playing poker and shot him in the back of the head.

From 1876 to 1881 Calamity was in and out of Deadwood. In man-deluged, female-starved Deadwood, Calamity became an in-demand worker, hostess and dancer in the boomtown saloons and lively theaters. But a transformation was necessary. “Boys,” she told the men camped with Wild Bill and Charlie Utter, “I wish you would loan me twenty dollars. I can’t do business in these old buckskins.” The men dished out the money, and the redressing worked. A few days later, Calamity returned to the men’s camp dressed attractively as a woman. “She pulled up her dress,” one eyewitness recalled, “rolled down her stocking and took out a roll of greenbacks and gave us the twenty she had borrowed.” Saloons and all-night dance halls, theaters and the ubiquitous, indefinable “hurdy-gurdies” offered positions to the very small group of women as hostesses, entertainers and “dance hall girls.” Calamity worked in several of these establishments but mostly in the Gem, ruled over by the unsavory manager Al Swearingen, who turned the theater into a “notorious den of iniquity.”

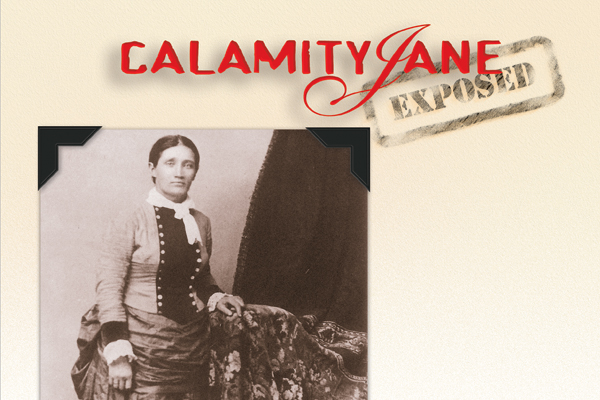

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

One observer claims that it was “generally well-established that Jane was a prostitute.” Perhaps, but unproven. No irrefutable evidence exists that Calamity sold sex in Deadwood. That she worked in houses of prostitution and hog ranches, where the main occupation was selling sex, and that she had several “husbands” without benefit of clergy is established. Still, no patron of the “joy palaces” nor any madam or worker therein ever testified to Calamity’s being an out-and-out prostitute.

During the Deadwood years, strong evidence suggests Calamity often served as a nursemaid for the sick or a helper for the needy. Granted, sometimes these stories of Calamity as Ministering Angel seemed attempts to balance harsh criticism of her unwomanly and socially aberrant acts. Illustrating this ambivalence are the stories of Jesse Brown and A. M. Willard, two early arrivals in Deadwood. At first they labeled Calamity as “nothing more than a common prostitute, drunken, [and] disorderly.” They quickly countered that negativity by praising her efforts as a nurse, particularly during a devastating invasion of smallpox. Other sources were more certain of Calamity’s positive actions. One memoirist remembered her as “the heroine of the Deadwood smallpox epidemic.” Another recalled her as “a perfect angel sent from heaven when any of the boys was sick.”

Editor’s Note:

“Calamity Jane: Devil in Buckskin” is excerpted from Richard W. Etulain’s Calamity Jane: A Reader’s Guide (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015). He is also the author of The Life and Legends of Calamity Jane (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), which True West’s editors plan to excerpt as a full-feature cover story in the near future.