— All Photos by Courtesy PaulHorsted.com Unless Otherwise Noted —

“GOLD!” proclaimed Dakota Territory’s Bismarck Tribune, August 12, 1874. Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s Black Hills expedition had discovered gold. The newspaper predicted the Black Hills would “become the El Dorado of America.”

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty established Dakota Territory’s Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation prohibiting white access, but the government believed forts were needed in the Black Hills. General William T. Sherman authorized Custer to lead an expedition to reconnoiter potential fort locations. The Black Hills were relatively unexplored, shrouded in mystery. Many hoped the expedition would confirm rumors of gold.

— C.F. Bates, April 6, 1874, Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University —

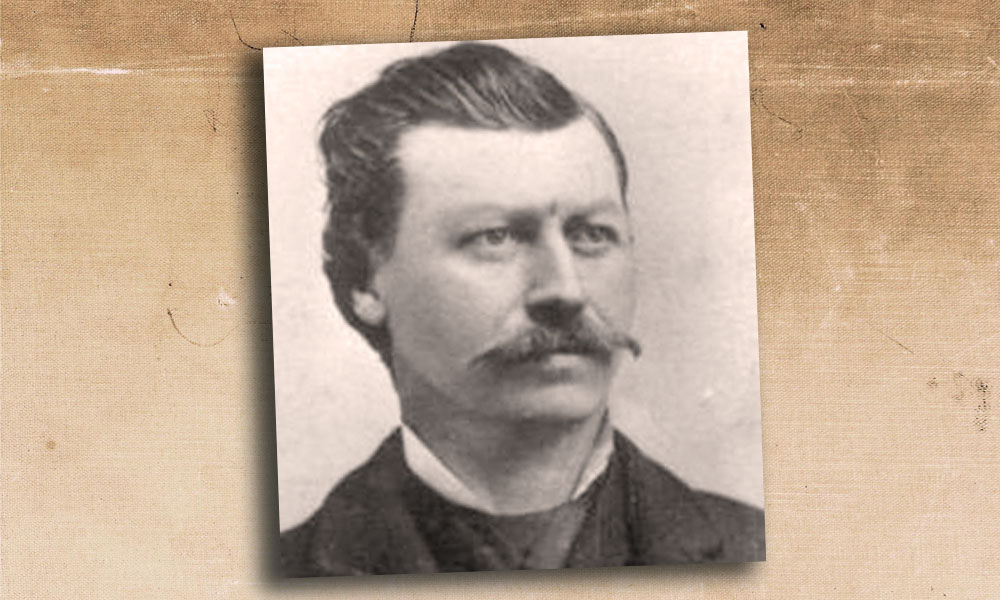

Custer organized his expedition at Fort Abraham Lincoln along the west bank of the Missouri River, Dakota Territory. The expedition comprised ten companies from the 7th Cavalry, one from the 17th Infantry, and one from the 20th Infantry, three Gatling guns, and a Rodman rifled cannon. Captain William Ludlow led an engineering detachment. Personnel included Indian and white scouts, a sixteen-piece band, teamsters, reporters, scientists, photographer William H. Illingworth and two miners.

On July 2, 1874, the band played “The Girl I Left Behind me,” as Custer, dressed in buckskin and riding his horse, Dandy, led 995 soldiers and civilians, 660 mules pulling 110 wagons, 700 horses and a large herd of beef cattle westward from Fort Abraham Lincoln. Using sextants, chronometers, compasses and odometers, Ludlow’s engineers recorded the expedition’s route as well as its 47 campsites, later creating maps.

— Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism —

Paul Horsted, Ernie Grafe and Jon Nelson have been enthralled with Custer’s trail for years. Studying maps, survey notes and journals, they rediscovered the trail and campsites, publishing their findings in two books. They overlaid Ludlow’s maps with GPS coordinates, pinpointing locations along the trail. As technology advanced, they superimposed Ludlow’s maps over Google Earth maps, further refining their search. They found most of Ludlow’s observations extremely accurate, considering distances involved.

I tagged along with Paul and Jon traveling Custer’s route as they reminisced about rediscovering the trail. “I became involved when I realized the expedition passed near my Black Hills home,” Paul said. He searched for Illingworth’s photograph locations, taking photos from the same positions. “I have used celestial navigation the same as they did, and set out to discover their camps using it,” Jon said.

Custer’s Black Hills trail begins at Fort Abraham Lincoln located on North Dakota Highway 1806, seven miles south of Mandan, North Dakota. Custer’s 7th Cavalry was stationed there in 1873. Today, one can visit reconstructed barracks, stables and blockhouses, and tour Custer’s house furnished the way it was when George and Libbie lived there.

Bearing southwest, crossing a treeless prairie under a scorching sun, plagued by clouds of choking dust, and slurping warm alkaline water, the expedition was led by Lakota scout Goose to Hiddenwood Creek on July 8. They rested by a grove of trees growing along the creek. You can find the Hiddenwood campsite on US Highway 12, 3.3 miles east of Haynes, North Dakota. A roadside display explains the expedition’s camp location.

July 11: They reached the Cave Hills. Goose led them to a sacred cave which Custer named Ludlow Cave. The cave is on Custer National Forest land, but hard to find. Obtain site information from the National Forest Service, and adjacent property owners. Driving can be difficult over rough roads. When hiking to the cave, watch for rattlesnakes.

July 21: The expedition crossed today’s Interstate 90. At the interstate’s Northeast Wyoming Welcome Center, a sign explains Custer’s expedition passed three miles to the west. The Crook County Museum in Sundance, Wyoming, and the High Plains Heritage Center in Spearfish, South Dakota, display expedition artifacts discovered by Jon Nelson.

Pvt. John Cunningham died from diarrhea on July 21. The next morning, Pvt. William Roller found his horse cross-hobbled which would not allow it to move without falling. Pvt. George Turner believed Roller was accusing him of the deed. The two men, who had been feuding, reached for their revolvers. Roller shot Turner in the stomach, killing him. Cunningham and Turner were buried in a double-grave. Their markers stand along the eastside of Wyoming Highway 585, 14.5 miles south of Sundance.

July 23: Custer and a small group climbed 6,500-foot Inyan Kara. A trail leads to the top on Black Hills National Forest land, but it’s surrounded by private land. Ask permission before crossing.

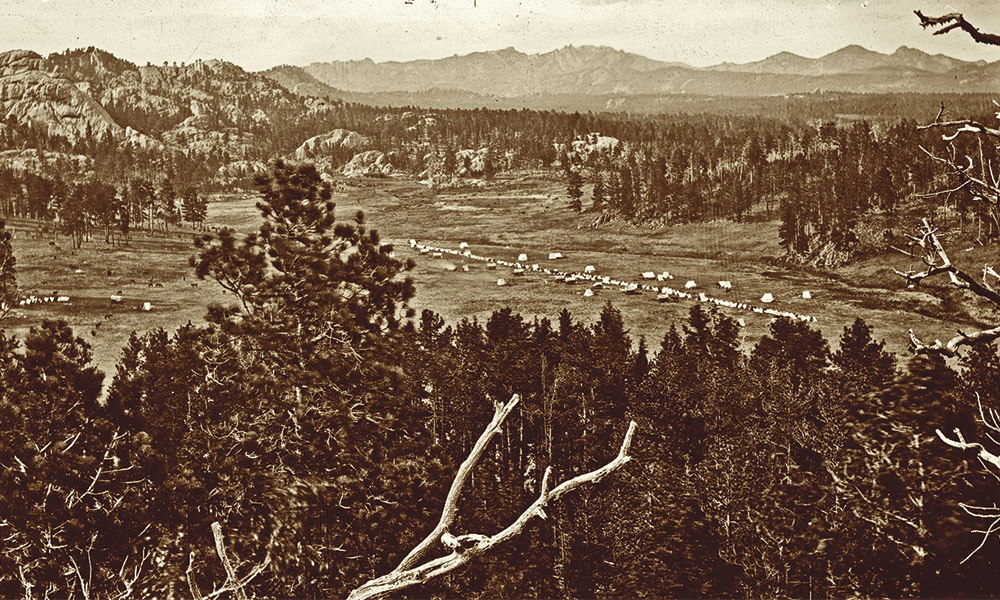

The expedition entered the Black Hills on July 25, and on July 26, they proceeded into Castle Creek valley from the northwest. Illingworth climbed a ridge to take an iconic photograph of the wagons in the valley. From the back end of Deerfield Lake, drive northwest 1.2 miles on Deerfield Road. Turn left onto West Deerfield Road. Drive 5.3 miles; look right for an old logging road. Stop and look to the southeast for two limestone columns. Illingworth’s photo site is on the ridge above.

That same day, they encountered a Lakota village led by One Stab. Custer’s Indian scouts prepared to attack, but Custer stopped them. He allowed the villagers to leave, but held One Stab as a guide. The expedition camped by Castle Creek, July 26 and 27. From Illingworth’s photo site, return toward Deerfield Road; just before the intersection is the expedition’s camp on Forest Service land.

— Courtesy Custer County 1881 Courthouse Museum —

July 30: They camped two days in present-day downtown Custer, South Dakota. The miner Horatio Ross, panning soil in French Creek, discovered a few gold pinpoints. Custer, leading a small group, climbed Harney Peak. While he was gone, the officers drank champagne after the men played baseball. Harney Peak, now renamed Black Elk Peak, at 7,244 feet, is accessible by several trails, the most scenic has its trailhead at Sylvan Lake.

The expedition moved three miles downstream on French Creek, camping for five days. Here, on August 2, miners Ross and William McKay discovered gold flakes, enough to consider profitable. East of Custer, where American Center Road crosses French Creek, is where they found gold. US Highway 16A cuts through the expedition’s campsite. Camp where the expedition camped at either Wheels West Campground on the northside of the highway or at Custer’s Gulch Campground on the southside.

The expedition began its return trip on August 6. The next day, Custer and a few others were in advance of the column when they encountered and killed a grizzly bear. This site is on private land.

August 13: The Army expedition forded Boxelder Creek then blazed a trail through Custer Gap. You can view Custer Gap on the east side of Nemo Road, three-tenths of a mile east of the intersection of Nemo and Norris Peak Roads.

That evening, Pvt. James King died of dysentery. He was buried the next morning as the expedition headed east out of the Black Hills. You can see King’s gravestone on private property on the westside of Nemo Road, approximately two miles southeast of Custer Gap.

The Army marched along the Black Hills’ eastside, camping five miles south of Bear Butte on August 14 and 15. From Sturgis head east on South Dakota Highway 34. Two miles past Fort Meade, turn south on Fort Meade Way. After two miles, a marker on the east side designates the campsite.

A small group of scientists and officers climbed Bear Butte, which rises 1,200 feet above the prairie. Sacred to the Cheyennes, Lakotas, and others, Bear Butte is a state park. To reach Bear Butte, take State Highway 79, 2.5 miles north of South Dakota Highway 34. As an Indian sacred site, visitors are asked to respect those in prayer and not to disturb offerings.

The expedition proceeded north over prairie studded with massive buttes. Taking South Dakota Highway 79 north to Castle Rock will keep you in the expedition trail’s proximity.

Follow South Dakota Highway 168 west then north on US Highway 85. Custer’s trail bears northwest of the highway toward Camp Crook on the Little Missouri River. No paved roads are close to the trail, so take US Highway 85 to Interstate 94.

Custer’s trail joins Interstate 94 at Gladstone, North Dakota. The interstate follows the Northern Pacific Railroad survey route, and this is the route Custer took returning to Fort Abraham Lincoln. Nearing the fort on August 30, correspondent William Curtis wrote “…the mules of the wagon train lifted up their voices and wept for joy.” After traveling 883 miles, the expedition returned with the band playing “Garryowen.”

Jon and Paul discussed the results of their work. Most landowners had no idea the expedition crossed or camped on their land. Now many are stewards of the sites, taking precautions to protect them. Paul has experienced eureka moments: examining Ludlow’s hand-drawn map at the National Archives, taking photographs where Illingworth did, and finding the spot Custer posed with his grizzly bear.

“You can see tree stumps in Illingworth’s photos that are still there today,” Paul said.

“The trees were dead in 1874,” Jon added. “And look, the trees are still dead today!”

A few campsites elude Jon and Paul. “It would help if people at the National Archives, West Point or the Minnesota State Archives, could find Ludlow and his men’s fieldnotes,” Paul said. “There are five known diaries out of an expedition of one thousand people. There’s got to be more.”

If you follow Custer’s trail, take along Paul and Ernie’s book Exploring with Custer and Paul, Ernie, and Jon’s book Crossing the Plains with Custer. Most campsites are on private property or you need to cross private land to reach them, so make sure you have permission. Be prepared to travel unpaved roads. Let someone know your travel plans. Ensure you have food and water in case you break down. Use sunscreen and bug spray. Watch for rattlesnakes. Taking these measures will enhance your experience as you follow Custer’s Black Hills Trail.

Bill Markley, author of Deadwood Dead Men, thanks Paul Horsted and Jon Nelson for taking him along on a Custer’s Black Hills Trail road trip.