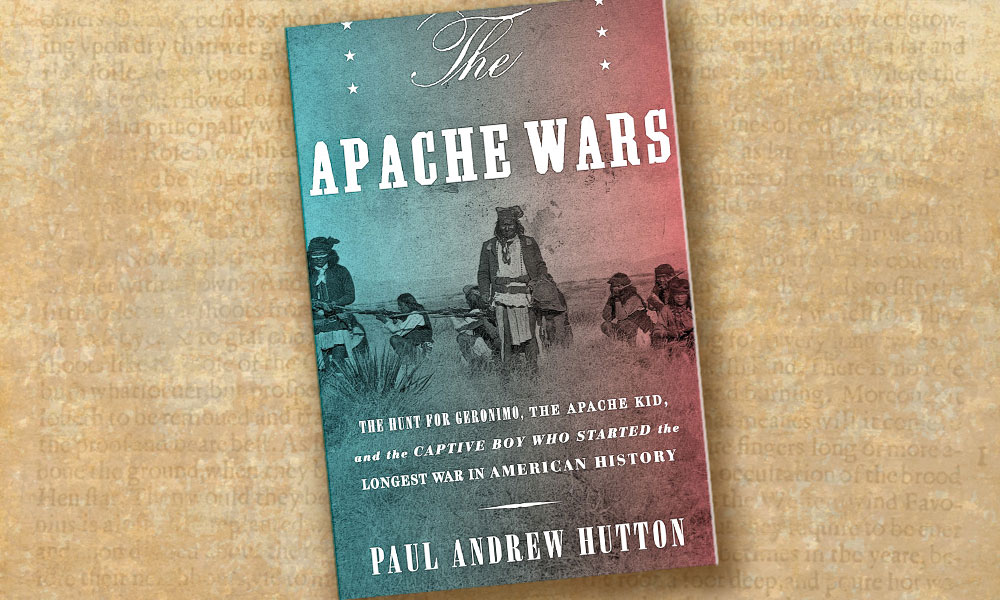

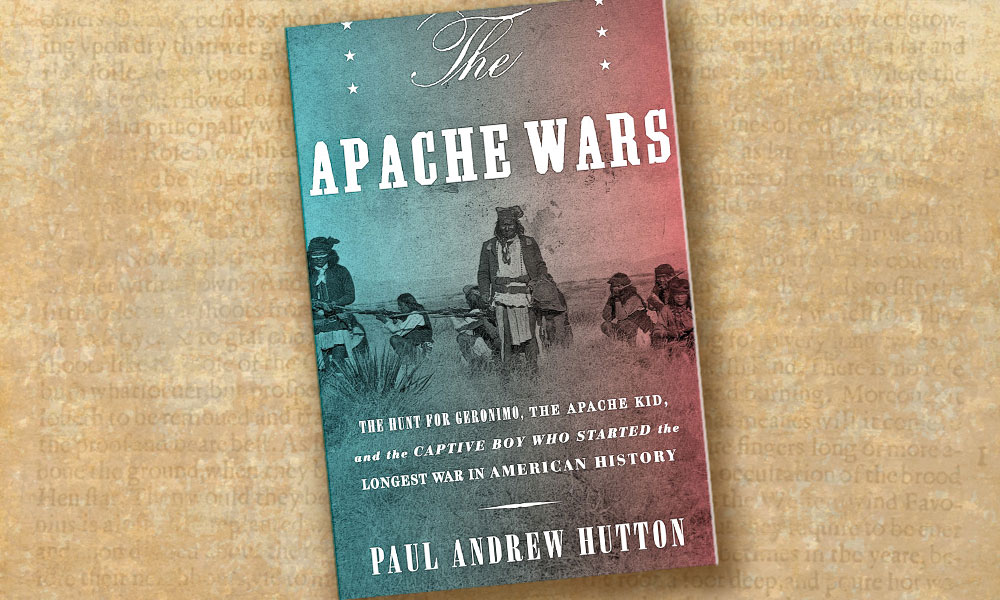

In the Bible’s Book of Revelation, John the Apostle prophesizes the coming of the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse: Conquest, War, Famine and Death. Paul Andrew Hutton’s The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy who Started the Longest War in American History (Crown Publishers, $39) offers readers the most comprehensive military synthesis of the United States’ longest international border war. Hutton’s vivid and dramatic prose will lead readers to wonder if the 18th- and 19th-century people of the Southwest believed that the Four Horseman had been unleashed amidst their homelands in one of North America’s most murderous wars of fratricide. “Unprotected by the army, the Mexican peasants were helpless to resist the Apache raiders, with scores carried off into captivity and hundreds more slaughtered. …Skeletons lined the roads, littered the burned haciendas, and were picked clean by scavengers in deserted villages. It was a perfect reign of terror.”

For historians and students, Hutton’s The Apache Wars definitively and dramatically redefines the violent conflict between the indigenous Athabaskan people of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Sonora and Chihuahua and the citizens, militias and armies of the United States and Mexico from the 1861 to 1886. He also provides a succinct, contextual history of the Spanish entrada into the region from the 16th century to the 1840s, the beginning of the American era in the Southwest that is prelude to the unmerciful decades that follow. The University of New Mexico historian’s decision to focus on the years 1861 to 1886—beginning with the kidnapping of Felix Ward and the Bascom Affair and ending with Geronimo’s surrender and the removal of the Chiricahua from the Southwest—neatly bookends the international civil war.

Many who read Hutton’s synthesis of the bloody conflict will be reminded of the highly detailed and readable prose of popular historians William Manchester, Barbara Tuchman, David McCullough and David Halberstam—as well as Western chroniclers Robert Utley, David Lavender and Bernard DeVoto. Hutton’s ability to synthesize such a well-known, complex, academic, ethno-historical topic, and create empathy for a cast of hundreds into a page-turning tale of pathos, triumph and tragedy is both remarkable and masterful. The endnotes and bibliography provide the reader with insights that could keep the most interested student reading about Apache history for years, but will long for Hutton’s next distillation.

The author’s first submission to Crown Publishers could have been two or three volumes, which leads me to wonder who or what will be the Albuquerque-based historian’s next topic? Will Hutton return to flush out the life and legend of the Apache Kid, whose biography clearly could be a stand-alone volume? Or the story of Mickey Free, a tragic human being whose proverbial life seems immemorial? In the interim, Hutton’s masterful chronicle of The Apache Wars is both a homily and eulogy: a homily about the scourge of Conquest, War, Famine and Death, and a long-overdue eulogy for windswept spirits of the dead long forgotten in the dark, blood-stained canyons of Apachería.

—Stuart Rosebrook