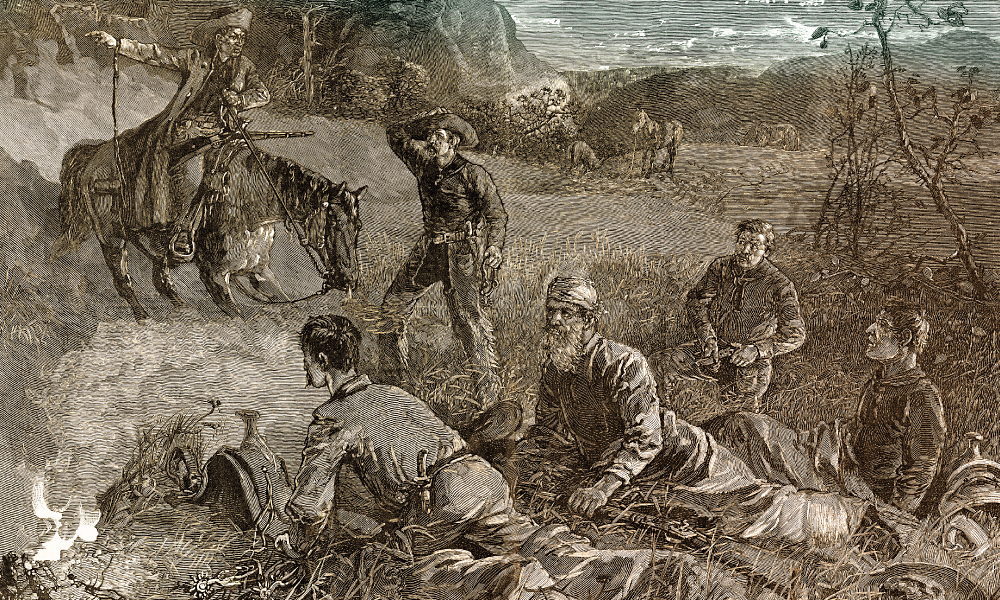

– Published in Harper’s Weekly, February 25, 1882 –

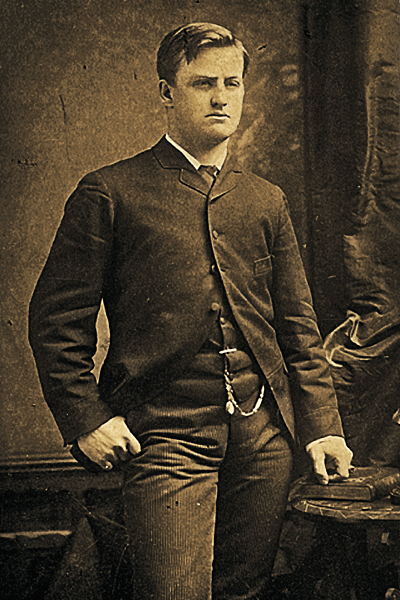

At the age of 19, Frederic Remington had yet to find a purpose in life when he boarded a train west on August 10, 1881. By August 13, he was in Dakota Territory, switching from railway to stagecoach on his way to Montana. Hundreds of miles away, where Arizona, New Mexico and Old Mexico meet, August 13 marked the violent death of Newman Haynes Clanton, a patriarchal Westerner whose unruly brood, unsavory friends and questionable activities would encourage mythmakers to transform him into a Godfather of borderlands crime. The two events were unrelated in every way except in the imaginative mind of a young and as yet undisciplined artist.

Like many young Easterners, Remington was on vacation, but he had an eye to finding get-rich-quick opportunities. He found none except those, like ranching, that required far more capital than he could put his hands on. But he did soak up the country, the big sky, the jagged mountains and endless prairie, the disappearing bison and the first Montana and Wyoming cattle herds. He saw, sitting effortlessly upon their horses, the cowboy, the cavalryman and the Indian, the latter no longer free to roam the Northern Plains.

Although Remington brought no artist’s tools with him on the journey, his experiences in Montana and Wyoming encouraged the young man to draw using any tools at hand. Remington had sketched illustrations for his college newspaper, but he had never offered anything for sale. The rugged land and men inspired him and reinforced self-confidence in his artistic ability. From Wyoming, he dispatched to Harper’s Weekly illustrated magazine in New York a sketch that became his first sold work of art, one that bore an eerie resemblance to a bloody massacre that ended the life of Newman Clanton.

Clanton’s Last Breath

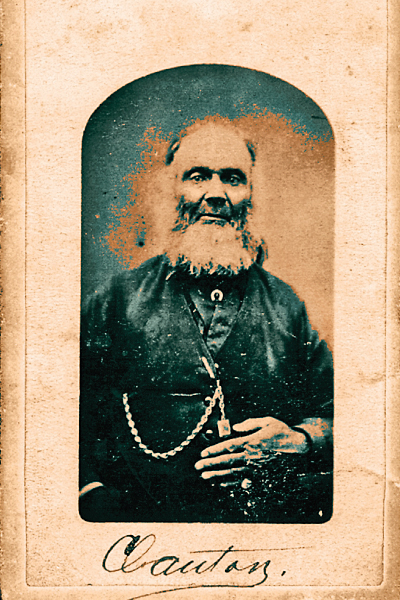

In the early morning hours of August 13, 1881, while Remington was still making his way to Montana, Old Man Clanton, as the 65-year-old Arizona rancher is more widely known, leaned over a campfire to get breakfast started for himself and six companions. The camp was yards north of the Mexican border in Guadalupe Canyon, a well-traveled corridor of legal commerce and contraband cattle straddling Arizona and New Mexico Territories.

The herding of cattle west from New Mexico’s Animas Valley had brought to the canyon that August seven Americans—four herders and three tagalongs looking for safety in numbers. Because the seven were a mixed-bag company of murderous criminals and honest cattlemen (or what passed for honest along a section of border where smuggling was rife), we do not know for sure the nature of their business. Were the herders driving their own cattle, or beeves recently stolen during a raid inside Mexico? Was Old Man Clanton simply the cook, or was he a leader of a band of rustlers? The argument goes on.

At least five of the group, including Clanton, were awake in the pre-dawn light, but all were figuratively caught napping that morning. The party had settled themselves and the livestock into a hollow surrounded by three hills. Near daybreak, the cattle became uneasy.

– Courtesy Frederic Remington, ca. 1880 / Notman Photographic Company. Mary Fanton Roberts Papers, 1880-1956. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution –

Billy Byers, who survived, was awakened by the noise. He heard Bill Lang, naturally fearing a stampede, call out to Charley Snow, at that time mounted and on guard, “Charley, get your gun, I think there’s a bear up there, and if so, kill it.”

Snow rode up a hillside past Clanton, who was preparing breakfast. Then gunfire erupted from all directions. The first volley, as many as 25 or 30 shots, killed Snow and peppered the entire campsite. Harry Ernshaw saw Clanton “fall face forward into the fire he had started for breakfast.” Dixie Lee “Dick” Gray and Jim Crane were still in their bedrolls where bullets struck them multiple times. They never rose. Bill Lang was killed exchanging shots with his attackers. Within minutes, a force of Mexican soldiers, taking revenge for the ravaging of Sonoran ranches and villages by American smugglers, had killed five of the cattlemen and their companions. Only Byers and Ernshaw made it out alive.

From Wyoming to Arizona

The massacre of five Americans in Guadalupe Cañon made The New York Times and other major newspapers from Chicago to San Francisco. If any of these dailies reached young Remington during his adventures on the Northern Plains, they might have stirred his imagination. That he read or heard the story in any detail is highly doubtful, which makes the imagery of his first sold artwork an uncanny coincidence.

More than likely, some story told to the aspiring artist by a Wyoming cowboy or cavalryman gave him the idea. Perhaps he was inspired by his own personal experience. We don’t know, because Remington recorded few recollections of his first trip out to the West. Whatever moved him, Remington formed a mental image, roughly translated it with pencil onto a piece of crumpled wrapping paper and mailed the resulting sketch to Harper’s Weekly, one of the premier periodicals noted for the work of graphic artists.

In New York, Harper’s Weekly’s art director Charles Parsons examined the sketch. “Intrigued” by the Wyoming postmark and by the rough drawing on even rougher paper, Parsons decided that Remington’s illustration was right for the magazine, once a bit of polish was applied. He turned it over to 27-year-old William Allen Rogers, already a veteran fine-line illustrator and the heir to Harper’s most famous cartoonist, Thomas Nast. Rogers took the original sketch and redrew it on wood.

Following his return to New York in October, Remington met with Harper’s Weekly editor George William Curtis, who agreed to buy the artist’s wrapping paper sketch, although we don’t know the purchase price.

Harper’s Weekly finally published Rogers’ redrawn version of Remington’s sketch in the February 25, 1882, edition. The image served as a companion to an article titled, “The Cow-Boys of Arizona.” That item drew upon messages from acting Arizona Territorial Gov. John J. Gosper and President Chester A. Arthur to describe the lawlessness of the cowboys, the ineffectiveness of both the county sheriff and city police in dealing with the problem, and the need for military intervention in support of civil authorities. The accompanying wood engraving, although based on Remington’s experiences in Montana and Wyoming, was titled, “Cow-Boys of Arizona—Roused by a Scout.” The drawing was signed, “W.A. Rogers,” but the original artist was credited in the caption, “Drawn by W.A. Rogers, from a sketch by Frederic Remington.”

The redrawn sketch received full-page space. Rogers was a talented artist, but his unfamiliarity with the West may account for the six cowboys in the scene appearing seriously under-armed. Only two rifles and two knives can be seen among the group, although one cowboy might be carrying an unseen revolver on his gunbelt. Remington was not yet a skilled artist, but he was from the start a keen observer, and he likely had placed more weaponry at the disposition of these just-roused cowboys.

Art Imitates Life

In depicting the moment of the cowboys’ arousal by their scout, Remington opted not to portray a subject common to many of his works, a violent struggle-to-the-death. He instead chose to illustrate the threshold of danger, at least to an unseen herd, and quite possibly to the men themselves. The life-or-death character of the scout’s news is seen fourfold: in his rush into camp, by his horse’s sudden stop, in the disbelief, dread or determination in the faces of his companions, and in the quick strapping of a gunbelt by one alerted cowboy.

A look of grim resolve marks the visage of the salt-and-pepper bearded cowboy, a countenance that Old Man Clanton might have shown if Charley Snow had been able to warn his trail companions of Mexican soldiers on the heights, to which Remington’s scout is pointing. Of course, Remington is not illustrating a moment in Guadalupe Canyon. The artist had not yet been to Arizona. He probably had not read or heard of the massacre. And Snow never made it off the bluff to warn anyone. Snow, Clanton and two of their still-sleeping companions were killed without warning in the first volley.

Yet Remington’s scene strongly calls to mind the Guadalupe Canyon Massacre. The editors of Harper’s Weekly created the association through their decision to pair this Northern Plains illustration with an Arizona article. Nothing in the illustration gives away the men’s purpose in the canyon setting or their identification as rustlers. Instead, the caption brands them as “Arizona Cow-Boys,” a title given its criminal meaning by the accompanying article. The illustration presents these figures, in Remington’s phrase, as “men with the bark on,” frontiersmen who willingly placed themselves in situations fraught with dangers, including whatever they now faced. Here, evidently, the figures have put themselves in the right place to get attacked, possibly massacred, by unseen enemies on the heights.

Interestingly, the landscape of the Clanton massacre site is strikingly similar to what Remington imagined for his scene of early morning danger. Together, Remington and Rogers successfully captured the confused reaction of men just awakened by the dire warning issued by their scout, a response Snow likely would have received had he been able to warn of the impending danger. While the cowboys in Guadalupe Canyon were instead aroused by bullets raining down from the heights, the individual reactions of those who survived the first volley speak to fear, presence of mind and gutsiness in the face of certain death, qualities on the faces etched by Rogers. Perhaps the eeriest element of the Harper’s illustration is the arresting presence in the central foreground of the elderly, bearded man. His resemblance to Old Man Clanton is uncanny.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

Unknown to the eventual Master Artist of the American West, who conceived this remarkable drawing, art nearly imitated a real-life event, proving that, as a 19 year old on vacation, Remington already grasped, even intuited, how brutishly life could play its last hand in an unpredictable and violent land. Remington’s first drawing would be joined by thousands more illustrations, paintings and sculptures that helped create and solidify the myth of an adventurous and violent contest for the right to live life as one chose in the frontier West.

Arizona author Paul Cool won the Southwest Book of the Year, among other awards, for his first book, Salt Warriors: Insurgency on the Rio Grande. For more on Frederic Remington, he recommends you read Peggy & Harold Samuels’s Frederic Remington: A Biography and John Plesent Gray’s When All Roads Led to Tombstone, edited by W. Lane Rogers.