“I sold my photographs for twenty-five cents, and was allowed to keep ten cents of this for myself. I also wrote my name for ten, fifteen, or twenty-five cents, as the case might be, and kept all of that money. I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money—more than I had ever owned before.”

Geronimo Cashes In

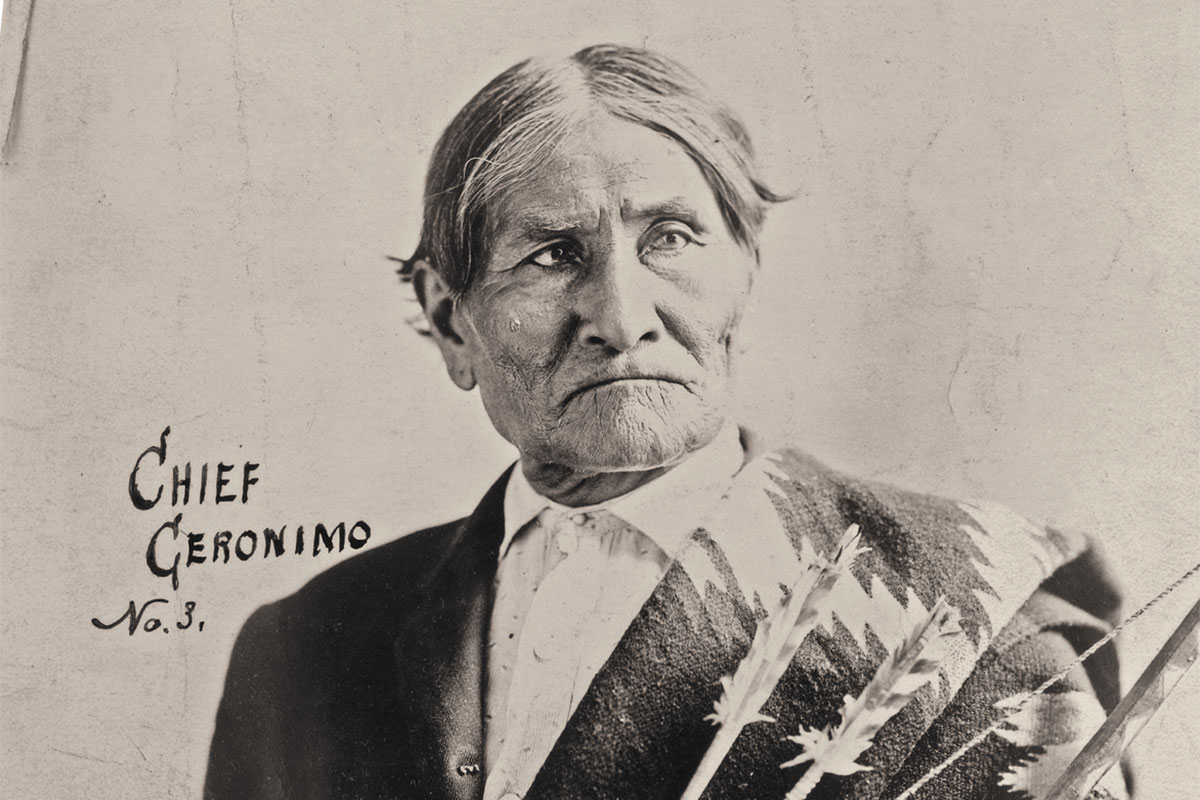

When the Apaches were transferred from Alabama to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1896, Geronimo had been a prisoner of war for ten years. It was during this period that Goyathlay and his brand name really started to take off.

In May of 1904 Geronimo is invited to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition being held in St. Louis. He’s offered a dollar a day, but settles on $100 a month. He stays at the fair for six months.

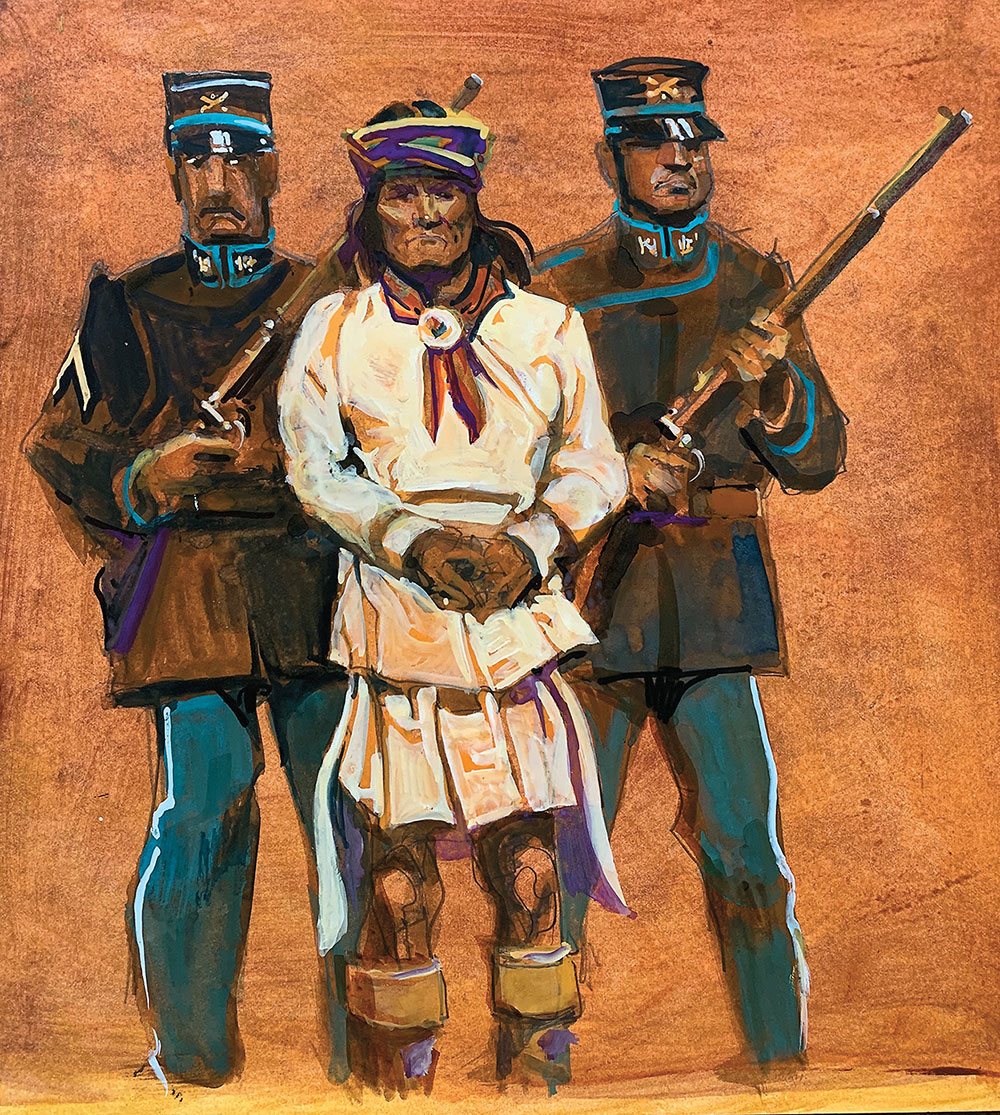

Geronimo is accompanied everywhere by two armed soldiers, who stand on either side of him. The effect creates the aura that the warrior is still dangerous, even though he is close to 76 years old. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the “prisoner of war” trappings, Geronimo is becoming quite a celebrity, and as he puts it, “Many people in St. Louis invited me to come to their homes, but my keeper always refused.

“I am glad I went to the Fair. I saw many interesting things and learned much of the white people. They are a very kind and peaceful people. During all the time I was at the Fair no one tried to harm me in any way. Had this been among the Mexicans I am sure I should have been compelled to defend myself often.”

March 5, 1905

Geronimo is invited to ride in Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. The Army gives him a check for $171 before he leaves (to pay for traveling expenses, etc.). Geronimo takes the check to Lawton, deposits $170 in his bank account and leaves for Washington DC with $1 in his pocket. He is not in need of cash, though—all the way to the capital, at every stop of the train, he sells his autographs as fast as he can print his name. When he runs out of photographs, he sells his hat, then the buttons off his coat. When the train leaves the station, Geronimo pulls out his suitcase and sews more buttons on his coat, and buys a new hat at the next stop.

When he gets to Washington the G-Man is asked where his horse is, and he tells them they will find him one. They do.

The inaugural parade moves along Pennsylvania Avenue with Teddy in the lead, doffing his silk hat and grinning his big-toothed grin. Next comes the Army band and then come six “wild” Indians. (This was supposed to be a “before” and “after” demonstration with the “wild” Indians followed by a unit of well-dressed, disciplined Carlisle cadets, showing off the government’s success in guiding the Indians to “civilization.”) The “wild” party, and Geronimo in particular, steal the show. No one even takes a picture of the Carlisle cadets—or remembers them in the parade. Geronimo is a huge hit and holds himself erect, completely calm and self-possessed. Men along the route throw their hats in the air and shout, “Hooray for Geronimo!” and “Public Hero Number Two!” A disgusted Woodworth Clum (son of former Apache agent John Clum) has been on the inaugural committee, and he takes the opportunity to ask Roosevelt, “Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President? He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American history.”

“I wanted to give the people a good show.”

March 9, 1905

Geronimo and a group of old-time warriors visit the White House. This is his chance to appeal to the highest authority for a return to Arizona. His appeal, interpreted by George Wratten, is touching: “…When the soldiers of the Great White Chief drove me and my people from our home we went to the mountains. When they followed us we slew all we could. We said we would not be captured. No. We starved but we killed. I said that we would never yield, for I was a fool.

“So I was punished, and all my people were punished with me. The white soldiers took me and made me a prisoner far from my own country…”

“Great Father, other Indians have homes where they can live and be happy. I and my people have no homes. The place where we are kept is bad for us…We are sick there and we die. White men are in the country that was my home. I pray you to tell them to go away and let my people go there and be happy.

“Great Father, my hands are tied as with a rope. My heart is no longer bad. I will tell my people to obey no chief but the Great White Chief. I pray you to cut the ropes and make me free. Let me die in my own country, an old man who has been punished enough and is free.”

Teddy Roosevelt answers him with compassion, tinged with hard-nosed political reality: “…I do not think I can hold out any hope for you. That is all I can say, Geronimo, except that I am sorry, and have no feeling against you.”

June 11, 1905

The National Editorial Association holds its annual convention in Guthrie, Oklahoma. An excursion by train brings the visiting editors to the 101 Ranch, where they witness “the tiger of the human race” and “the Apache terror” in person.

Geronimo is the main feature of the morning events and he shoots a buffalo (provided by Charles Goodnight’s JA Ranch in the Texas Panhandle) from a fast-moving car. This is where the photograph of Geronimo behind the wheel of a car is taken. The buffalo meat is served to the guests in the afternoon.

October 1905

Lawton School Superintendent Stephen M. Barrett approaches Geronimo about writing his life story. Geronimo agrees on the stipulation that Barrett can ask no questions. Geronimo also refuses to be questioned about details or to add another word. He simply says, “Write what I have spoken.”

After striking a deal with Geronimo (the wily old horse trader will get half of anything the author gets), Barrett tries to get the Army’s permission, but the officer in charge, George A. Purington, bluntly refuses, saying Geronimo should be hanged instead of being “spoiled by so much attention from civilians.” Barrett finally appeals directly to President Teddy Roosevelt, and after a series of communications through channels (five pages of fine print, ten endorsements and six weeks of bureaucratic paper shuffling), permission is approved on the stipulation that the manuscript be submitted to the Army before publication.

July 4, 1907

After attending a parade and picnic in Cache, Oklahoma, Geronimo starts home in the evening but turns south and hides in the timber (speculation is that he was drunk). The newspapers have a field day reporting he is on his way to join the still-hostile Apaches in Old Mexico (he’s 84 years old!) The soldiers find him the next day and bring him back to Fort Sill.

February 12, 1909

Not far from Geronimo’s house, Mrs. Jozhe sees his horse saddled on the bank of a creek. She and others investigate and find Geronimo lying partly in the water. They deduce that he was thrown from his horse on the ride home and has been lying in the cold water, unconscious, all night.

February 15, 1909

A severe cold has turned into pneumonia. One of the scouts has told the post surgeon, who sends an ambulance to Geronimo’s house. The bedridden war leader is surrounded by about a dozen Apache women who refuse to let him go to “the death house,” which is the Apache name for the hospital. Finally, returning with a scout, the ambulance brings the old warrior in. The post surgeon expects him to die within the next few hours, but Geronimo asks that his son, Robert, and his daughter, Eva, be brought from Chilocco.

February 17, 1909

For two days his strong spirit has refused to give up until he could see his children one more time. They have not arrived. Now, at 6:15 a.m. he closes his eyes and surrenders for the last time.

February, 18, 1909

The funeral is at three o’clock. The Army grants a half-day work furlough for the Apache men so they can attend. Robert and Eva finally arrive by train and the funeral procession starts for the cemetery.

Before the grave is filled, relatives solemnly place his riding whip and blanket in the casket. (Before he died, Geronimo told his wife to tie his horse to a certain tree and to hang up his belongings on the east side of his grave, and in three days he would come and get them.)

When his bank account is checked in Lawton, it is revealed that Geronimo had more than $10,000 in the bank at the time of his death! It turns out the old boy had cashed in on his fame. In today’s money, this would be more than a quarter of a million dollars.

After Geronimo’s death, Asa Daklugie and Eugene Chihuahua pushed the U.S. government hard to let the Apaches in Oklahoma return to the Southwest. With World War I approaching fast, the U.S. Army was all too willing to rid themselves of the burden, and so, in the spring of 1913, most of the Fort Sill Apaches (some chose to remain in Oklahoma) loaded all their household goods, people and dogs on a train which took them to Tularosa, New Mexico. Members of the Mescalero Apache tribe met them at the train station with wagons and they began their long trek up the mountain, to a new life.

Geronimo had at least 10 wives (some historians say 12) and his last wife, Zi-yeh, gave him a daughter, Eva, when the old warrior was 66. Zi-yeh also gave him a son, Fenton, who was about six when Eva was born. Eva was the apple of Geronimo’s eye and he worried about her and doted over her. Eva had her womanhood ceremony in September of 1905 when she was 16. She started to show signs of debilitating illness and Geronimo became convinced a witch was doing it so he had a local medicine man, Lot Eyelash, do a ceremony to identify the witch. During the ceremony, the witch turned to Geronimo and said he was the guilty party and had traded the sickness of his children so that he could love longer. That Lot Eyelash lived to see another day is pretty hard to believe.

From this point on, Geronimo refused to let Eva marry anyone. So, on his deathbed, Geronimo sought a promise from his nephew, Asa Daklugie, which Eve Ball finally coaxed from the reticent old Apache.

Geronimo took care of the domestic chores of his children and his extended family after Zi-yeh came down with a tubercular infection and died. He washed dishes, swept the floor, cleaned the house, and treated the children kindly. He was devoted to his Eva, born in 1889. One visitor said, “Nobody could be kinder to a child than he was to her.”

Geronimo’s Final Request

“He moved. I bent over him and took his hand. His fingers closed on mine and he opened his eyes.

“‘My nephew,’ he said, ‘promise me that you and Ramona will take my daughter Eva into your home and care for her as you do your own children. Promise me that you will not let her marry. If you do, she will die. The women of our family have great difficulty, as Ishton [Daklugie’s mother] had. Do not let this happened to Eva!’

“He closed his eyes and again he slept, but restlessly. When he spoke again he said, ‘I want you to promise.’

“Ramona and I will take your daughter and love her as our own, but how can I prevent her from marrying?”

“‘She will obey you. She has been taught to obey. See that she does.’

“He died with his fingers clutching my hand.”

–Asa Daklugie, telling Eve Ball what Geronimo said to him on his deathbed

Daklugie and his wife, Ramona, did, in fact, take in Eva, and she married Fred Godeley (a.k.a. Golene) sometime in the fall of 1909. She had a daughter, Evaline, born June 21, 1910. Evaline died August 20, 1910. Eva died of tuberculosis on August 10, 1911. All of Geronimo’s fears came true. In spite of the glorious success he had made out of his prisoner of war status, the tragedy of his life was the fate of his favorite daughter.