– Andrew J. Russell, Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

GOLD!! The glittering metal that dreams and fortunes are made of. California in 1849 and Alaska in 1896 were the most well-known American gold rushes, but Wyoming had three major gold strikes from 1850 until 1895. The biggest was at South Pass City, and went on for ten years; Centennial, in the 1850s, and Bald Mountain City, in the 1890s were the three most promising areas for gold. Let’s follow the miners on their journeys through Wyoming.

Southeastern Wyoming

The first strike was in 1850, when gold was discovered near Keystone, Wyoming. Later, Cheyenne, Wyoming, was the jumping off point for many miners, as the UP Railroad came to Cheyenne in November of 1867.

– Cynthia Vannoy –

Although it wasn’t built until 1911, the Historic Plains Hotel in Cheyenne is representative of hotels of the late 19th century. Small rooms, a restaurant on the ground floor and, what was probably a real luxury in the 1911, an elevator. The elevators are original, and very tiny, the story being that it kept cowboys from bringing their horses into their hotel rooms.

I enjoyed my stay at the Plains Hotel, and felt as if I had stepped back in time. Don’t be surprised by the size of the rooms; they do have all the modern amenities.

In 1875, Col. Stephen W. Downey of Laramie discovered gold in the Medicine Bow Mountains on Centennial Mountain. As miners and prospectors started coming to the area, they established a community in 1876 and named the town Centennial in honor of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

– Image Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

Laramie City, founded in 1868, was the hub of industry, where miners bought supplies before heading into the Medicine Bow mountains in search of gold, and then came back when the streams froze and the snow locked in the mountains.

Most of the gold was gone by 1877, but Centennial endured and it is still a small town today, complete with a small museum, two cafes, a bed and breakfast and a motel.

The Mountain View Hotel was built in 1907 in time for the July 4th celebration of the first train to Centennial. At the time, the hotel cost $8,000 and featured 20 guest rooms, a dining room and a “most improved system of plumbing.”

It was restored, and in 2007 boasted six guest rooms and suites all with private bathrooms, though the history of the building has not been diminished with these modern amenities.

Although the Mountain View was booked up the week I was there, I did eat at the Bear Tree Cafe, which serves not only burgers but interesting sandwiches, such as the Tomato Hummus. There is also a tavern and an outdoor patio that has live music from local musicians.

– Image Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

Centennial, an hour’s drive from Laramie, sits at the base of the Medicine Bow Mountains. There are still several remains of miners’ cabins and old mines around the town and up into the Medicine Bows. Several hiking trails lead to the old cabins and the old mine sites.

South Pass City

Going north, following the gold strikes, the best known gold camp in Wyoming was South Pass City. First established as a stage, Pony Express and telegraph station on South Pass along the Oregon Trail, the original town was about ten miles southwest of the gold mining community and was only two miles from South Pass. When the Overland Stage company abandoned the northern route due to Indian hostilities and moved south, the first South Pass City was abandoned.

In August 1861, Samuel Clemens (later known as Mark Twain) passed through the first South Pass City on his way west. He wrote about the experience in Roughing It, first published in 1872: “…we have in sight of South Pass City…South Pass City consisted of four log cabins, one of which was unfinished.”

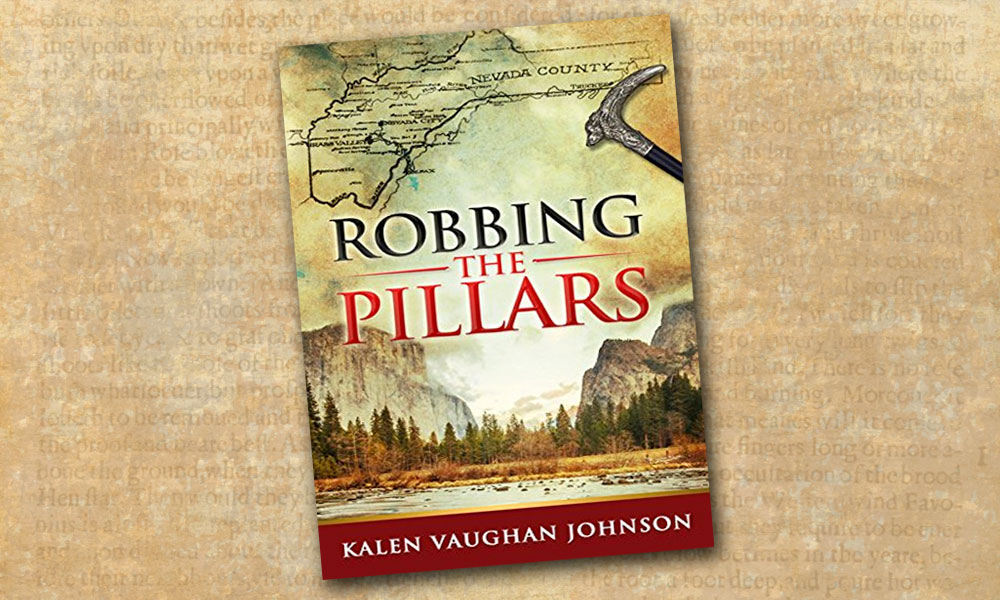

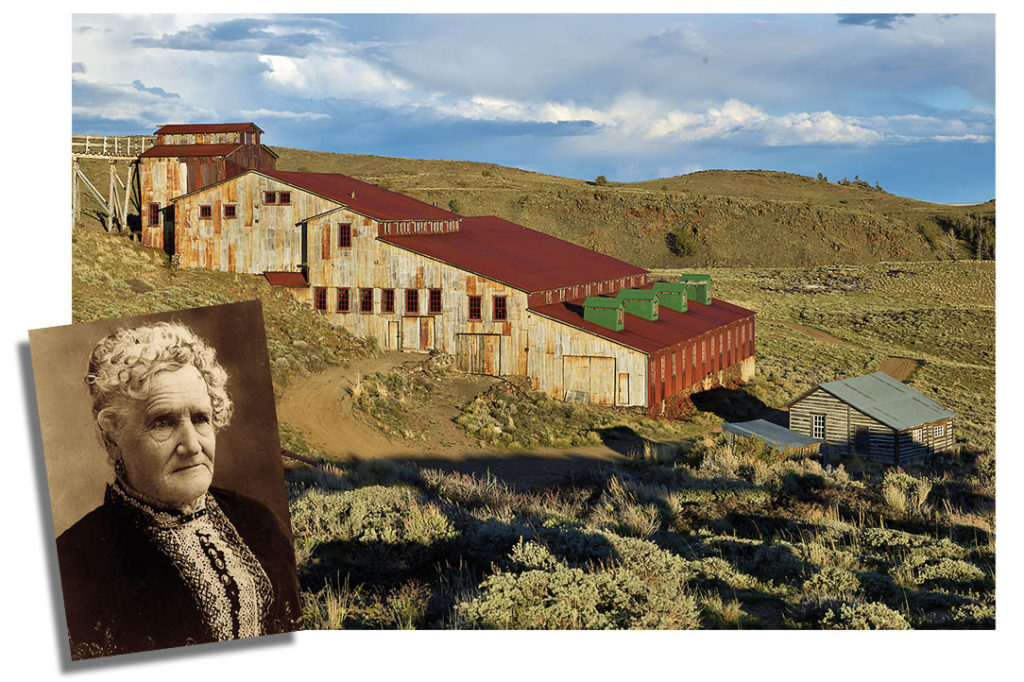

– Esther H. Morris Photo Courtesy Library of Congress/Carissa Mine Photo Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

When gold was discovered in 1866, the town grew up nearer the mines, but the founders decided to retain the name, South Pass City. Two other towns, Miner’s Delight and Atlantic City, also grew up. Miner’s Delight is gone, but Atlantic City has about 50 residents, and a merchantile/cafe that serves a variety food and drink.

The mine that made the town is the Carissa Mine, about a half mile above the town. Although a great deal of gold was produced, many owners of the mine had bad luck and it changed hands several times over the years of operation.

The gold boom lasted about ten years, then the gold declined, although some gold and silver are still being mined today. In 1867 the community boasted about 2,000 people. One of the better known residents was Esther Hobart Morris. In 1870 she became the first woman in the United States to serve as a justice of the peace and was instrumental in helping to introduce a bill to give Wyoming women the right to vote in 1869. Nationally, woman suffrage did not become law until 1920.

Today, South Pass City is an authentic and well-preserved ghost town that gives a sense of what it was like to live during that bygone era. Thirty historic buildings stand on 39 acres of land. A yearly festival, Gold Rush Days, recreates the glory days of the town.

The nearest town is Lander, about an hour away. We stayed at a fairly new hotel/casino, Shoshone Rose. The large rooms offer scenic views from their large windows. We ate at the Cowfish Restaurant in downtown Lander. I mean, with a name like that you just have to try it. Food is rather pricy, but excellent, with an innovative menu of steaks, seafood and pasta dishes, and a full bar—a good place to enjoy a relaxing evening when in the area.

– Image Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

Big Horn Gold

The last gold strike was in 1892, when a mining company purchased a group of claims in the Big Horn Mountains, near Sheridan, Wyoming. Discoveries of fine-grained gold north of Bald Mountain were made in 1890. In 1892, the Fortunatas Mining and Milling Company purchased a group of claims on the head of the Little Horn River and Porcupine Creek. The excitement led to the establishment of Bald Mountain City, the most extensive attempt at a settlement in the Big Horn Mountains. At one time there were as many as 50 buildings, including a saloon, meat market, an “eating house,” a hotel, blacksmith shop, general store and drug store.

In 1895, with talk of a rich vein being discovered, mining machinery was hauled up the steep slopes by ox team from Dayton. Fortunatus poured about a half million dollars into the effort, and in late 1896, Fred D. Smith, mining engineer at the University of Montana, exposed the claims as being exaggerated. Although some mining continued near Bald Mountain City as late as 1903, the gold was not commercially viable.

– Image Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

After several attempts on a road that was rougher than I wanted to travel, I finally found, if not the Bald Mountain City townsite, at least Half-Ounce Meadows, along Half Ounce Creek, where a great deal of panning went on. I found one ruin near there, and although the logs appeared to be hand-hewn and of the era of the late 1800s, there was no concrete evidence that it was a miner’s cabin during the time of the gold rush.

Another ruin is about five miles away, on a high, rocky, windy ridge that also was constructed of very large hand-hewn logs, and could have started life as a miner’s cabin. Seeing as the elevation of the area is around 9,000 feet, with deep snow in the winter, cold winds and chill temperatures, it is little wonder that the settlement didn’t survive.

Because the gold rush lasted for the six years that the Sheridan Inn was being constructed (1892), and the inn was right next to the railroad, it is safe to assume that some of those with gold fever stayed at the Sheridan Inn on their way to Bald Mountain City. Today, the Historic Sheridan Inn is a fine hotel, with 22 modern rooms furnished in the period, although at present there is no restaurant on the premises.

Early prices at the inn were $1/day for a room, 25¢ for breakfast and 50¢ for lunch or dinner.

From Centennial, through South Pass, and the Carissa Mine; to as far north as Bald Mountain City, Wyoming’s gold mining towns added a rough and rugged side note to the history of Wyoming.

– Image Courtesy the Wyoming Office of Tourism –

Cynthia Vannoy still lives on the Wyoming ranch where she was raised. She enjoys researching and writing about Wyoming and frontier history, and traveling, especially to historic sites and museums.