– All Images by Stuart Rosebrook Unless Otherwise Noted –

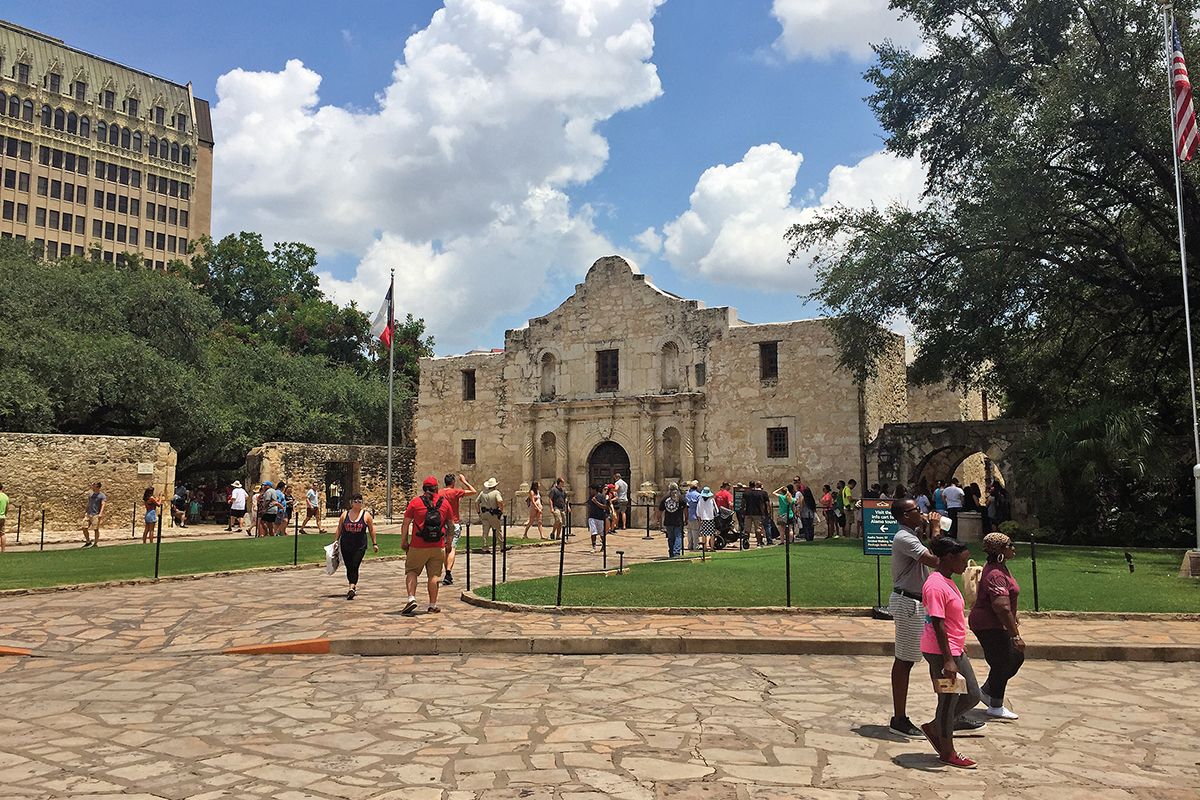

Gary Foreman is in a new phase of life. Some good. Some not so good. Much yet to be determined. But the man who is the visionary behind the Alamo restoration project, the effort to return the mission to its 1836 configuration, seems a bit calmer these days.

Some of it is personal. A few months ago, his wife, Carolyn Raine Foreman, died after a long illness. She had been the kinder and gentler force on the Alamo project, balancing out Gary’s insistence, persistence and pushiness. Gary seems more contemplative, more thoughtful in conversation.

Or maybe it’s because his vision—at least part of it—is finally becoming reality, some 38 years after it came to him on a visit to the Alamo. The project’s Phase 1 is now underway. Included in that are street closures around the Crockett and Menger Hotels, to the south of the mission. Parts of Bonham Street, located behind the area, will be widened. Landscape design architecture and lighting will be installed on the south end of Alamo Plaza from Crockett Street to the mall. And the massive Cenotaph, located in the plaza, will be restored. All of that should be done by the fall of this year. That means larger parts of the project—including moving the Cenotaph, tearing down buildings to the west of the Alamo, and building a museum—are still in the future.

And it’s those plans that still draw most of the opposition.

Members of the Conservation Society of San Antonio, along with some black groups, want the Woolworth Building saved. It’s located just west, across the street from the current plaza. But in 1836, that spot was part of the western wall of the Alamo. Built in 1921, the building has a history of its own. In 1960, it had one of the first lunch counters in the South to desegregate. Supporters want that history preserved and honored. But the interior of the Woolworth is in bad shape and would require massive work to restore it to its former appearance. San Antonio City Councilman Roberto Treviño, who’s on the Alamo Master Plan committee, says, “We have an agreement with the Alamo museum to make sure that we tell the story of the Woolworth Building and how it played a critical role in the civil rights story of San Antonio.” So far, that still hasn’t placated those who want to keep the Woolworth Building from facing the wrecking ball.

In November, three sets of human remains were found during archaeological digs at the Alamo. As of this writing, tests are continuing to determine how old they are and to what ethnicity they belong. Soon after, leaders of the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation filed suit to stop any construction at the site and instead to focus work on finding any more remains on the premises. The Tap Pilam believe that there could be a large number of Indians buried at the mission, which served local tribes for much of the 1700s. But there’s a problem. The Tap Pilam is not a federally recognized Indian tribe, so it lacks standing in court proceedings. And it has not been proven that the remains are, in fact, Indians. It should be noted that an Alamo archaeology committee overseeing the treatment of human remains found during digs includes members of federally recognized tribes. None of those groups have sought to stop work on the project.

The Alamo Defenders Descendants Association has filed suit and held protests to keep the Cenotaph where it is. The monument, which was built and dedicated on the centennial of the battle, honors all of those killed in the fight. The ADDA says that the Cenotaph is basically a headstone, marking the graves of some of the heroes of the Alamo. Supporters of the project deny that, saying all of the defenders’ bodies were burned and the ashes taken away. Lee White of the ADDA says the entire Alamo area should be treated as a cemetery; he fears that the reclamation project will turn it into an urban park. It should be noted that part of Phase 1 calls for the Cenotaph to be restored (it’s had little work done since its construction) and for the list of names on it to be corrected—some were inadvertently left off.

But even with all those bumps in the road, the Alamo project is off and running. Alamo Trust CEO Douglass McDonald says, “This is the home stretch, where we will actualize our goal of making Alamo Plaza a more reverent space to better honor the Alamo defenders. The plan is progressing as expected and is on track to be completed by 2024, in time for the 300th anniversary of the Alamo Mission moving to where it is today. Texans and visitors from all around the world will experience a world-class historic site that tells the whole story of the Alamo, where history happened.”

And as for Gary Foreman, the instigator, the bur under the saddle, the person Doug McDonald once called “tormented”? He hasn’t totally mellowed. He still wants the proposed museum to be located in the old post office building, located northwest of the plaza. He’s fighting the proposal to locate it to the west, where the Crockett Block now stands. When he talks about that, some of the old Foreman fire comes out again.

But now he also talks about bringing people together. “As we see this enter a higher professional realm, I think there will be a lot of people that will understand the interconnectedness of everything—whether it be religion, or military, or economic, or whatever. And that’s where we start healing, when we see it that way.”

Perhaps for Gary Foreman, the healing has already started.

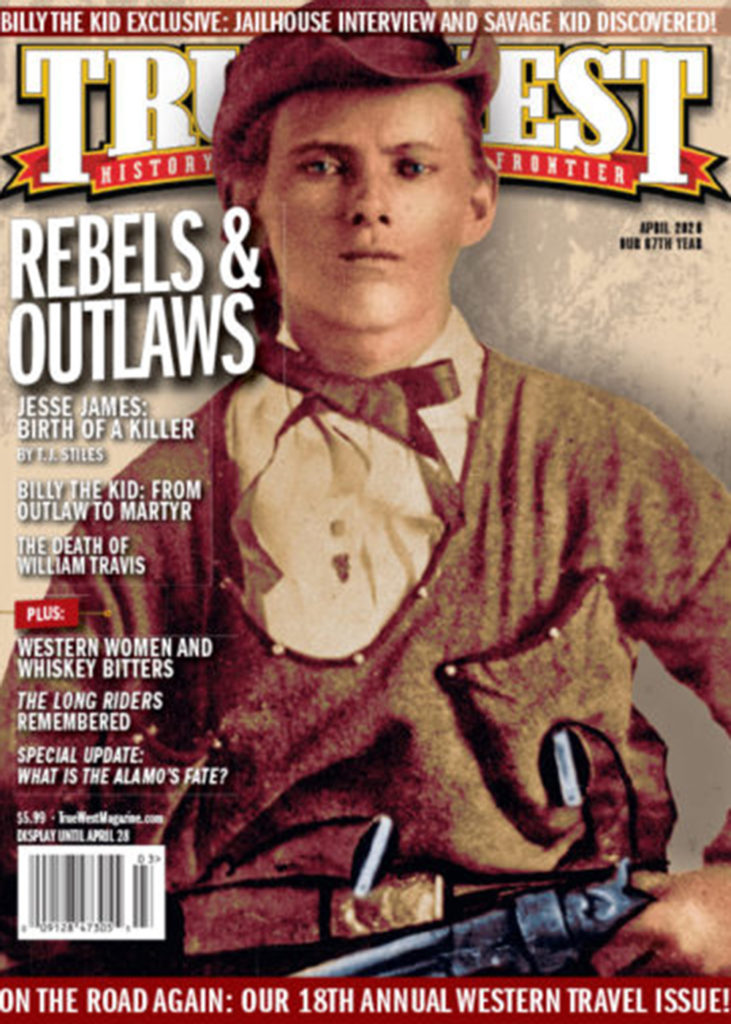

Editor’s Note: Interested in knowing more about the Alamo Restoration project, including past, present and future phases? Visit the Alamo’s website at TheAlamo.org. For an in-depth feature on famed Alamo commander William B. Travis and the controversy surrounding his death fighting for Texas independence, turn to page 50 to read William Groneman’s “And Die Like a Soldier.”