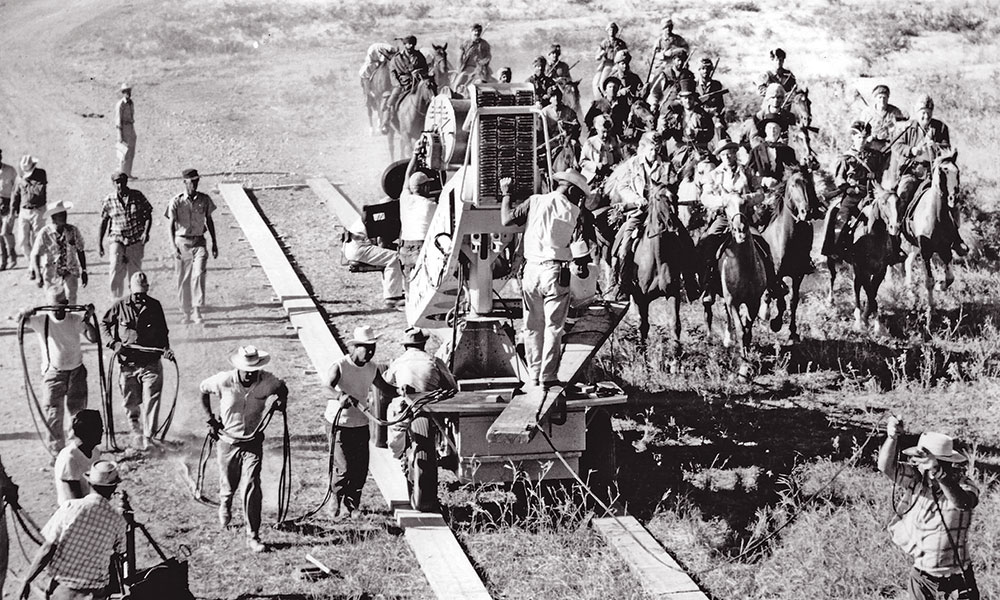

— Courtesy United Artists —

The Western, be it a novel or a film, always carries with it the burden of history. For much of our nation’s existence, the West was the story of America. Frederick Jackson Turner, our greatest historian, wrote that the American character—and thus American exceptionalism—came from the settlement of the frontier from Jamestown to Wounded Knee. That history provides the setting for every Western film: be it a historical epic, such as 1924’s The Iron Horse, 1936’s The Plainsman, 1941’s They Died with Their Boots On, 1950’s Broken Arrow, 1960’s/2004’s The Alamo or 1993’s Tombstone; a morality play, such as 1939’s Stagecoach, 1953’s Shane, 1943’s The Ox-Bow Incident, 1952’s High Noon, 1962’s Ride the High Country or 1969’s/2010’s True Grit; or even a whimsical farce, such as 1954’s Destry, 1965’s The Outlaws is Coming, 1959’s Alias Jesse James, 1962’s Sergeants 3, 1974’s Blazing Saddles or countless Gene Autry and Roy Rogers Singing Cowboy pictures. All are set in a seemingly mythical land and yet are grounded in a particular time and place—the American frontier.

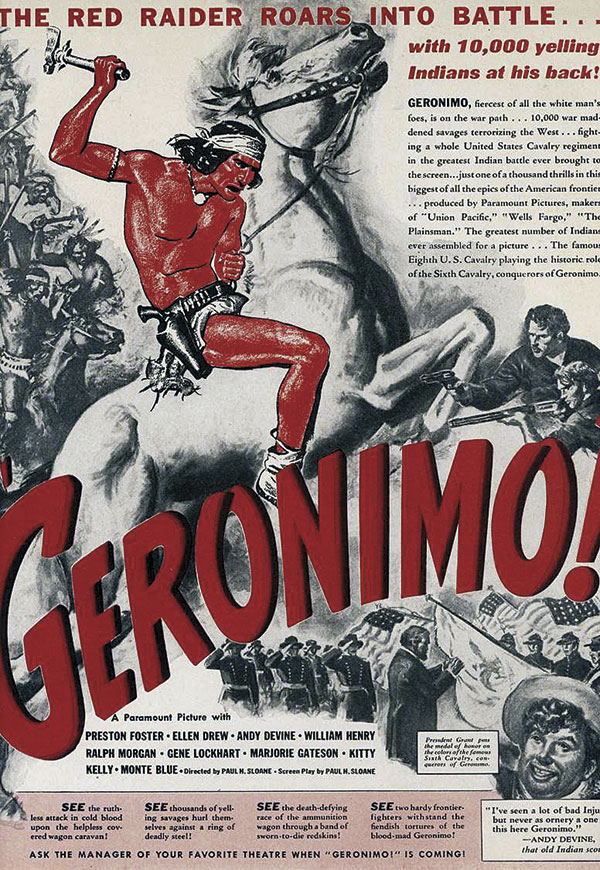

— Courtesy Paramount Pictures —

To seek points of accuracy in the Western film is at best a delightful parlor game, and, if taken too seriously, it is a fool’s errand, for every movie is essentially a three-act play. Once the first word of dialogue is written, it is a work of fiction. Thus every Western film, just like every Western novel, is fiction, not history, entertainment, not fact. Many so-called Western documentaries, with invented dialogue, are also fiction masquerading as history.

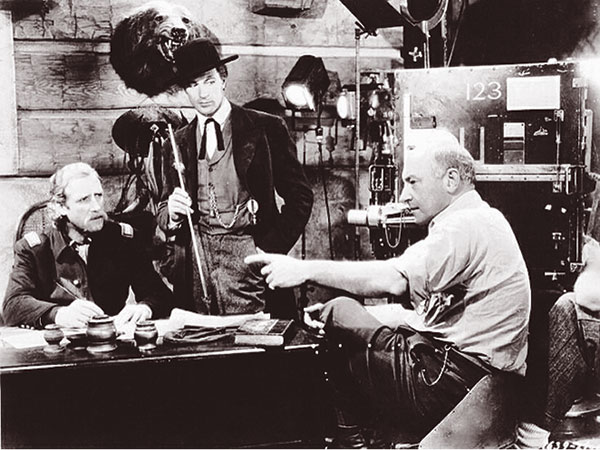

Westerns often go to great pains to be historically accurate in detail, but then go off the rails in terms of story. I call this The Plainsman syndrome, after one of my favorite films. In Cecil B. DeMille’s epic, the wallpaper and a ceramic statue in Gen. George Custer’s office are correct (copied from a famous photo of Custer and his wife, Libbie, that is in the DeMille research collection at Brigham Young University), but almost everything else in the film is wildly inaccurate. DeMille even had to fight with the studio to be allowed to kill Gary Cooper’s “Wild Bill” Hickok at the end of the movie—the studio heads wanted a happy ending.

— Courtesy MGM —

A nice touch can be seen in 1988’s Young Guns, the most historically accurate of dozens of Billy the Kid films—the pistol used by the Kid is the correct type. Tables turn though when the outlaw uses it to kill Jack Palance’s villainous Murphy at the film’s climax. This is a good piece of story development, but alas, some bad history.

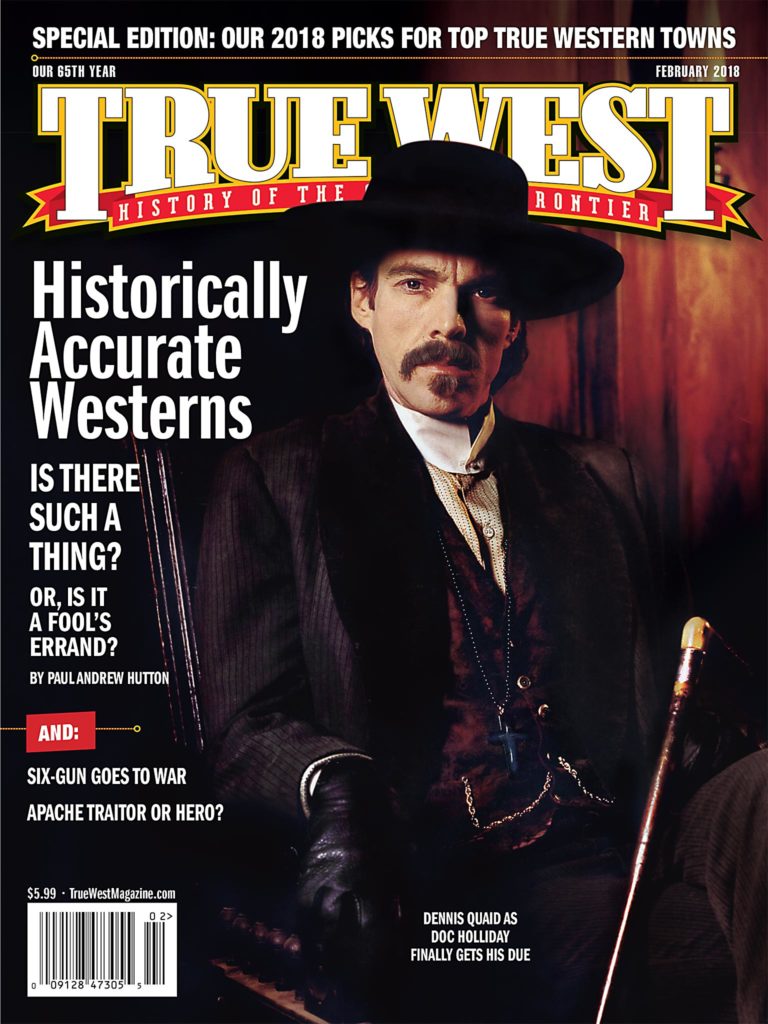

In 1993’s Tombstone, an elaborate dance of death is played out between Johnny Ringo and “Doc” Holliday so that the dead outlaw can be properly laid out under a tree with an accurate head wound (a detail grasped by only a handful of viewers). The only problem is that Holliday did not kill Ringo (see Classic Gunfights in this issue).

— Courtesy Paramount Pictures —

In 2004’s Alamo, great stock is put in historical accuracy. Yet the set designer changed the scale of the set, so that the famed chapel façade could be seen from most camera angles, and the costume designer placed almost all the defenders in top hats and frock coats, to distance the film from John Wayne’s buckskin-clad defenders in the 1960 version. It was as if every defender was a lawyer or businessman, not the farmers and frontiersmen they were at the time. Crockett is stripped of his signature coonskin cap as well. To make matters worse, Crockett is repeatedly called David, not Davy, and it is even pointed out in dialogue that he prefers to be called David. In reality, the famed backwoods politician was called Davy by contemporaries, even though he signed his name David.

In 2015’s The Revenant, Hugh Glass hunts down and kills the man who deserted him after the bear attack—once again a good story that satisfies the audience, but totally inaccurate history. More often than not, when a film claims in opening credits to be true to history, it often goes wildly astray—two classic examples are 1967’s Hour of the Gun and 1970’s Little Big Man.

My favorite historical Westerns tend to be those that get at the heart of why we remain so fascinated with the West and why that story still resonates today. John Ford was the undisputed master of this. Thus, my favorite Custer film is 1948’s Fort Apache, in which the names and locales are changed, but which perfectly explains the necessity of a false Western legend to our national identity. My favorite Wyatt Earp film remains 1946’s My Darling Clementine, in which almost every historical detail is wrong, and yet the mythic power of the Tombstone saga is perfectly captured. These films go to the heart of James Warner Bellah’s oft-quoted line from 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance—“This is the West sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

These historical epics are most valuable to students of American history as cultural artifacts. They reflect the time in which they are made, the political, cultural and historical vision of the filmmakers, and if they are successful the mood of the country that embraces them. Thus we can learn much about the mood of the country in 1941 and 1970 or in 1946 and 1993 by comparing the George Custer figure in They Died with Their Boots On and Little Big Man or the Wyatt Earp character in My Darling Clementine and Tombstone.

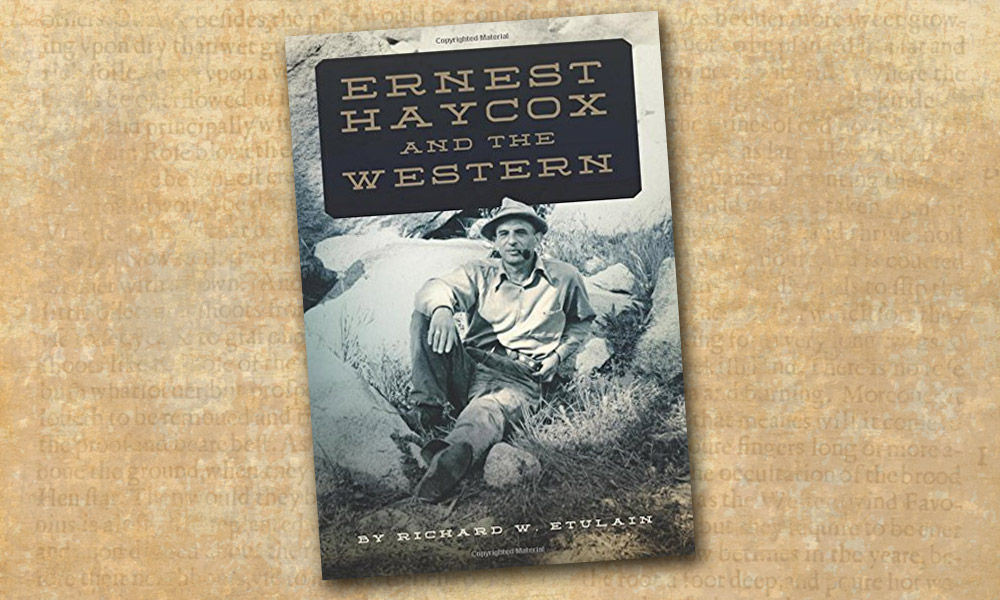

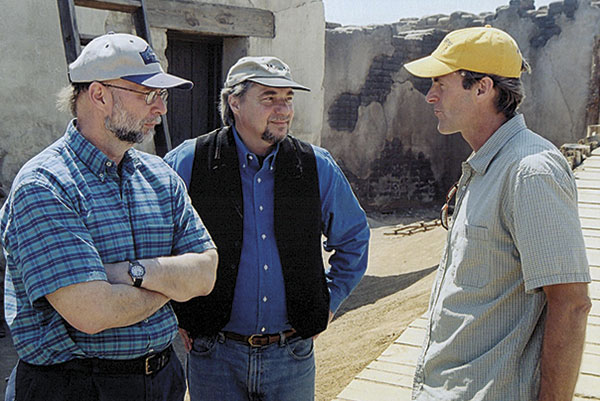

— Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton —

I love historical Westerns—both films and novels. My first interest in history came about as a result of Disney’s Davy Crockett in 1955, and my fascination with the Apache Wars can be attributed to Elliott Arnold’s novel Blood Brother and the 1950 film based on it (Broken Arrow). My love of the Custer story, however, came from the famed Cassilly Adams saloon print that hung in the bar my parents frequented in San Angelo, Texas. I studied that painting for hours while they drank. When I finally saw They Died with Their Boots On, I was confident that the painting and film were “correct in every detail”—a wonderful line about a history painting, from John Ford’s Fort Apache.

During the 19th century, historical paintings toured the country and, along with Wild West shows and stage plays, presented a version of frontier history for mass consumption. The conventions of these paintings and shows were later adopted by filmmakers. The cinematic image of Custer’s Last Stand comes directly from paintings (and, in DeMille’s The Plainsman, is essentially a living tableau of Alfred Waud’s famous Custer illustration).

The visual imagery from 19th-century canvas flowed easily into 20th-century celluloid. Be it a painting, a stage play, a novel or a film, it was always a constructed version of history with often scant resemblance to fact. The goal is entertainment, not education. As a famous producer once quipped: If you want to send a message, call Western Union!

The great legacy of these historical paintings, plays, novels and films about Western history is that they have inspired generations of Americans—including this writer—to further explore the frontier story and to delve much deeper into our nation’s history. They are the starting point of many a lifetime of adventure in history.

—Paul Andrew Hutton