While fighting for the citizens they swore to protect, two horseback-era Texas Rangers were cut down by a deadly killer.

Maybe in the flag-waving fervor following America’s April 2, 1917, entry in the Great War, 56-year-old Ben Pennington saw joining the Texas Rangers as a patriotic act. Too old for the military, Pennington per-

haps thought he could help guard the border from Mexican bandits or German spies and saboteurs. If he could not take on the Huns himself, he could take part in rounding up slackers (draft dodgers) or jailing anyone speaking disloyally of America.

For whatever reason, on October 4, 1917, Pennington enlisted as a ranger under Captain James Monroe Fox in Brewster County. Though new to the Texas Rangers,

Pennington had toted a pistol for two decades, a dozen years as marshal of the Central Texas town of Holland, followed by eight years as a Bell County constable. Heavyset with light hair and brown eyes, he stood 5 feet 10 inches.

An easygoing cowboy from San Angelo with light brown hair and blue eyes, 34-year- old Bob Hunt was as tall as Pennington if shorter in overall law enforcement experience. He had first signed on as a ranger in El Paso-based Co. B on June 8, 1915. The fol- lowing spring, on April 11, 1916, he resigned for reasons not noted on his records. But on August 20, 1918, the affable bachelor rejoined the Texas Rangers as a private under Co. L Capt. W. W. Davis.

Like most rangers, Pennington didn’t talk much about his business, but since first stepping off the train in far West Texas, he had heard the whine of bullets more than once. One of those slugs, though sparing his life, had cost him his right eye. Still, the ranger rode the river for Texas, keeping his one good eye out for trouble. He deserved his reputation for fearlessness.

When Co. L moved from the Big Bend to the El Paso area, the rangers camped for a time near Cline before moving to a farm adjacent to the Rio Grande near Fabens. Known to his comrades as “Old Dad,” Pennington served as company cook, using the farmhouse’s kitchen. The adobe house also served as a makeshift fortification on one occasion when rangers traded shots with suspected Mexican smugglers across the river. A large dinner bell atop the farmhouse provided cover for Pennington, who said to his fellow rangers, “I’ll fight ’em from behind the Liberty Bell, boys!”

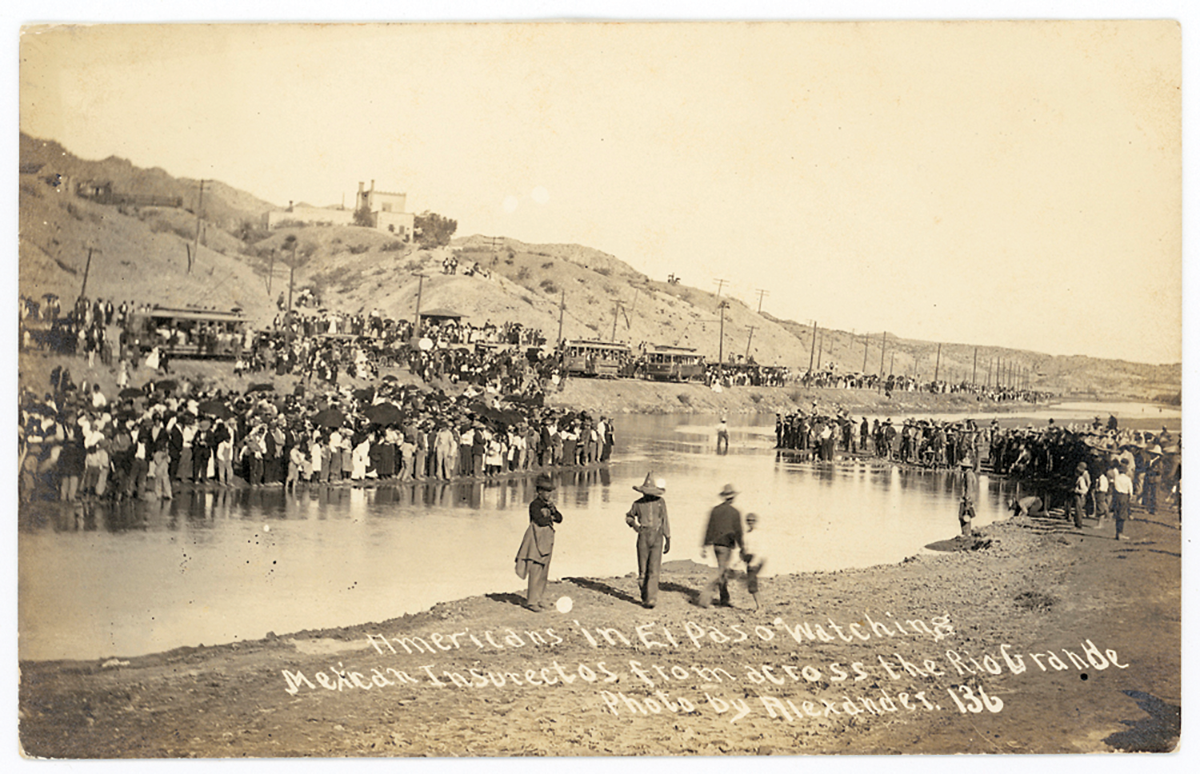

In addition to the outlaws plaguing both sides of the Rio Grande, another source of trouble along the border was El Paso’s Fort Bliss. On payday, when the soldiers hit the city’s 250 bars and numerous houses of prostitution, El Paso police often called on the Rangers to help keep the rowdy sol- diers in line. Local sentiment was to let the boys have a good time, within reason. The U.S. War Department, however, wanted El Paso and other Texas cities with large mili- tary posts to clean up their act. So did Congress, which passed wartime legisla- tion prohibiting the sale of alcohol as a food-conservation measure.

While America dried up in the social sense, as the prickly pear and ocotillo began to bloom in the desert around El Paso in the early spring of 1918, another form of change— albeit one that was quite random—occurred. Seven hundred miles northeast of El Paso, in a biological process that would not be even partially understood for decades, a normally stable avian virus migrated from a bird to a pig. When the pig’s immune system attacked the invader, the virus mutated to survive. Soon the resultant new strain sought a new host.

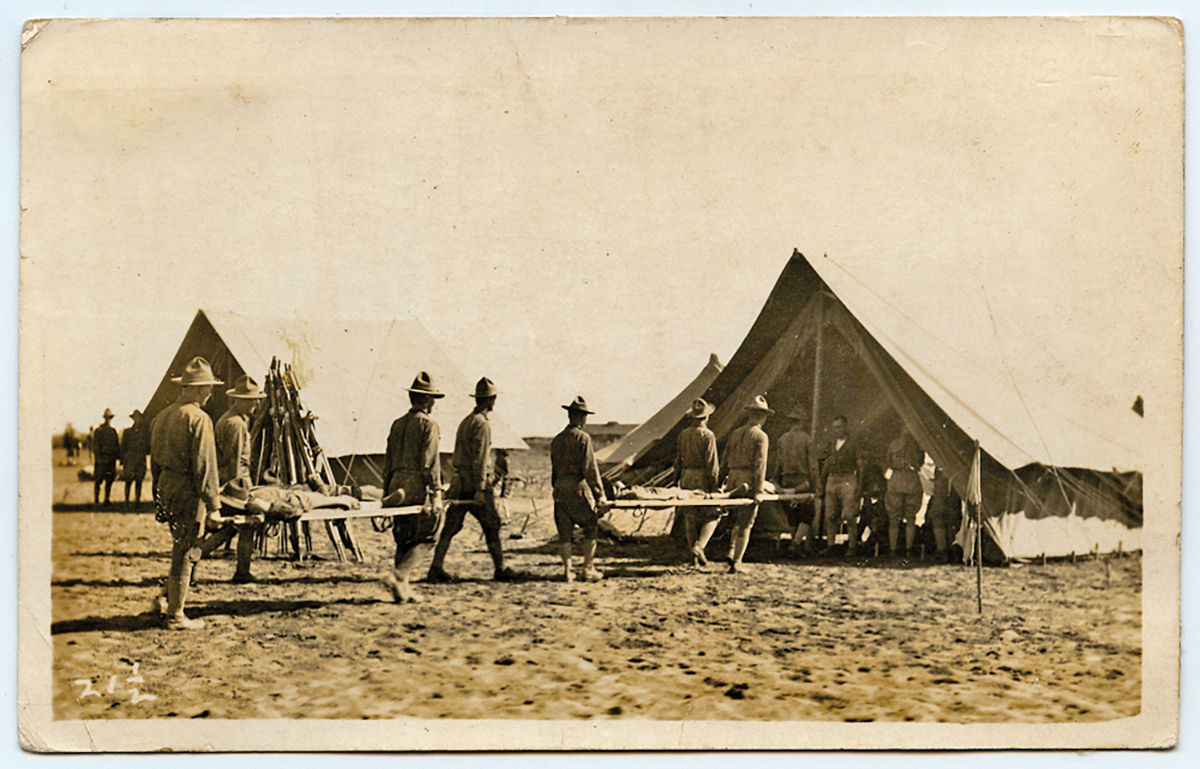

On March 11, company cook Albert Mitchell reported to the infirmary at Camp Funston, Kansas, a Fort Riley sub post. He had a slight headache, mild sore throat, and low-grade fever. His appetite was off, and his muscles ached. A post doctor put Mitchell on sick leave and ordered him to spend the day in his bunk. By midday, another 106 Camp Funston soldiers were ailing. Two days later the number of sick soldiers at the Kansas camp reached 522.

The disease quickly spread across the nation—from San Francisco Bay’s isolated Alcatraz prison to sailors aboard ships along the East Coast. Despite the disease’s rapid transmission, the medical community and the general public did not initially take it seriously. Recovery seemed as rapid as its onset. At first doctors referred to it as “three-day fever,” but they finally realized it was a new influenza strain. Soldiers in the trenches “over there” in Europe began calling it the Spanish flu, believing it had originated in Spain. But in Spain, people referred to it as the French flu.

Newspapers were crowded with war news—President Woodrow Wilson had just given his famous 14 Points speech—but little if any attention was paid to the flu epidemic. Meanwhile, the flu spread from post to post in the military. Soon the virus was well embedded into the general population.

In West Texas, ranchers also were getting sick of incursions by Mexican bandits. Raiders struck the Neville Ranch on March 25, killing two people. The next day, U.S. troops—accompanied by some of Captain Fox’s rangers—crossed the river and struck the suspected bandit stronghold in Pilares, Chihuahua, Mexico. In the wake of the Pilares attack, and an earlier Ranger action in the border town of Porvenir, Texas, that left 15 men and boys dead, Gov. William P. Hobby ordered Adj. Gen. Jason Harley to discharge five of Fox’s men. Seven other rangers received transfers to other companies. Pennington kept his job but got assigned to Company L, joining Ranger Hunt. Captain Fox resigned from the Rangers.

The flap eventually died down, overshad- owed by other events. As the great armies of Europe and America battled that summer in the deadliest war the world had known, each side gained another vicious enemy. Symptoms of the flu became more severe. Twenty percent of all sufferers developed life-threat- ening secondary infections: bronchial pneu- monia or septicemia blood poisoning. With antibiotics yet to be invented, a large per- centage died. Those who developed helio- trope cyanosis turned blue from lack of oxygen and within a day or two, 95 percent died. In America, many blamed the sickness on a secret German biological weapon. But the disease knew no flag or boundary. It deci- mated an already war-weary German army as well as that nation’s civilian population. From the Western front to the home front, tens of thousands died from a disease deadlier than bullets, shrapnel or mustard gas.

– ALL IMAGES COURTESY DEGOLYER LIBRARY, SMU, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED –

In El Paso, east-west railroad traffic and routine Fort Bliss troop rotation carried the disease to the southwestern desert, an area generally noted for its healthfulness because of its high, dry climate. On September 30, 1918, El Paso newspapers casually noted that some people in the city had the flu. A week later, nearly a thousand people lay sick. Then many of them began to die.

The situation worsened daily in early October. The city’s board of health ordered the closing of schools, churches,

theaters, lodges, pool halls and

other public places. All public meetings were canceled. In addition, Fort Bliss soldiers were confined to post, forbidden to pass beyond the intersection of Overland and El Paso streets.

El Paso officials asked the Rangers to help enforce the quarantine. Rangers Pennington and Hunt, along with others, were pulled from border duty to see to it that Fort Bliss troops, normally an economic asset, stayed on post. Armed with six-shooters that could do no harm to the real enemy they faced, Pennington and Hunt followed orders and tried to keep people put for their own good.

Soon, both lawmen began feeling ill. In following orders, the two rangers had contracted the flu. The disease progressed rapidly in both officers. Pennington died on October 12, only four days after becoming symptomatic. “Famous Fighter of Border Guard Finally Downed,” the El Paso Times reported the next morning. The newspaper noted:

Pennington was one of the oldest and best known men of the border guards. The story is told of one fight in which he and another Ranger entrenched themselves in the sand near the river and stood off alone a body of raiders, doing such deadly work with their rifles that the attacking bandits finally beat a retreat across the line. He carried 16 wounds in his body, the marks of various frays… Among his associates he was known as one absolutely fearless and one who could be depended upon to stick out any fight in which they were engaged.

Ranger Hunt survived only four days longer than his older colleague, dying in an El Paso hospital on October 16. In five days, his disease had progressed to pneumonia. With many of its reporters, editors and print- ers also sick, the Times barely noted Hunt’s passing. A one-paragraph article reported only that “Robert Hunt, state ranger, from Fabens, Tex., died in a local hospital Wednesday morning.”

The rangers and others afflicted with the flu died hard. One doctor described the pneumonia associated with the flu as “the most vicious type… that has ever been seen.” Once cyanosis appeared in a patient, the physician continued, “it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate.”

El Paso Mayor Charles Davis announced that 131 people, including the two rangers, had died locally the week of October 9-16, most from flu. Thirty-one people alone died on October 12. Nationwide, 10,561 people died that week from the flu. That figure did not include military personnel. Hospitals across the country were full but short-staffed, as many doctors and nurses were sick or dying. El Paso and other cities ran short of funeral directors, coffins and grave- diggers. The American Red Cross mobilized to meet a domestic crisis as severe as the one abroad.

The quarantine the Rangers helped enforce probably saved lives. In El Paso, flu deaths were more common at Fort Bliss and in predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods. “Army and civilian doctors continue confident that they have the situation under control,” the El Paso Times reported on October 14. “That the Spanish Influenza epidemic among the civilians has not been as serious as it might have been is indicated by the fact that only one death has occurred among the 1,500 members on the roll at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.”

– COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS –

In addition to the quarantine, good hygiene and wearing face masks also helped. Other methods, however, were ineffective. In Britain, the government sprayed streets with chemicals dangerous in their own right. Some thought tobacco smoke would kill the virus, or brisk walks, or eating plenty of porridge, or forcing yourself to sneeze once each morning and night after thoroughly washing the inside of your nose with soap and water.

In El Paso, the epidemic finally began to abate in November. On November 9, only 17 new cases had been reported. Three people a day were still dying, but that was a significant improvement from October. The viral siege was declared over, and public places were allowed to reopen. But Fort Bliss, still with 2,000 cases, remained under quarantine.

Three days later, at 1 a.m. on November 11, El Pasoans awakened to pistol shots and whistles. Soon the city’s two newspapers had extras on the street announcing in huge type that the war was over. A wild, spontaneous celebration swept the city, continuing through daybreak. Those not inclined to offer a toast to liberty headed to special church services. Honking cars jammed the streets. At 9 a.m. the commander of Fort Bliss sent his soldiers—mounted, in vehicles, and on foot— marching into town. Townspeople fell behind the troops as a victory parade wound through downtown.

People in El Paso and across the nation may not have realized it, but they were celebrating two victories—a military triumph over Germany and, for the time being, the defeat of a deadly virus. America had won a war, and its people had endured a terrible pandemic that due to wartime censorship had been even worse than they thought. The virus infected roughly 28 percent of all Americans, killing more than 600 people in El Paso (which had a population of 75,000) and an estimated 20,000 in Texas. Nationwide, some- where between 675,000 and 850,000 people died of the disease. The flu had claimed the lives of more American military men and women than German warfare. Worldwide, one-fifth of the planet’s population had been infected. Some 20 to 40 million people died in the worst pandemic the world had known.

Though the pandemic peaked in Texas during the fall of 1918, it continued elsewhere through the first few months of 1919. Suddenly, 18 months after it appeared, the virus vanished. Except for their families and friends, few remembered Pennington and Hunt—two horseback-era rangers who died in the line of duty trying to protect Texans from a killer bullets couldn’t stop.

Once a Ranger, Always a Ranger

“Young Texas Ranger Dies of Influenza,” read the headline in the October 18, 1918, edition of the Austin Statesman.

The brief article reported the death of Thomas Hughston Beverly from complications of the Spanish flu at the Army’s Camp Cody in Deming, New Mexico—101 miles northwest of El Paso. A lawyer from McKinney, north of Dallas, Beverly came from an old-line Texas family. His late father had been a respected district judge in Collin County, and his uncle had served as a sheriff in West Texas.

While indeed a pandemic victim, the 32-year-old Beverly had resigned from the Rangers the previous summer for a higher-paying job as a U.S. Department of Justice agent. First stationed at the border town of Eagle Pass, he had recently been transferred to New Mexico.

– MIKE COX –

A bachelor, Beverly had joined the Rangers on December 29, 1917, and served in Company M until resigning effective May 31, 1918. Prior to his Ranger service, he had been in private legal practice in McKinney. From 1914 to 1916, he had held office as a Collin County justice of the peace.

Though trained in the law, the future law enforcement officer clearly knew how to handle a firearm. That came in handy on December 5, 1915, when an ex-con named Carroll McCown assaulted the judge in his courthouse office. Newspaper accounts did not say whether McCown was armed, but Beverly was. The JP fired four shotgun blasts into the man, blowing off the top of his head. The killing was ruled self-defense.

Beverly had visited his mother in McKinney only two weeks before his death. When she received word that her son had become ill after returning to New Mexico, she rushed to Deming to be at his bedside, but he died before she got there. Beverly’s body was returned to Texas, where he was buried in McKinney’s Pecan Grove Cemetery.

—M.C.