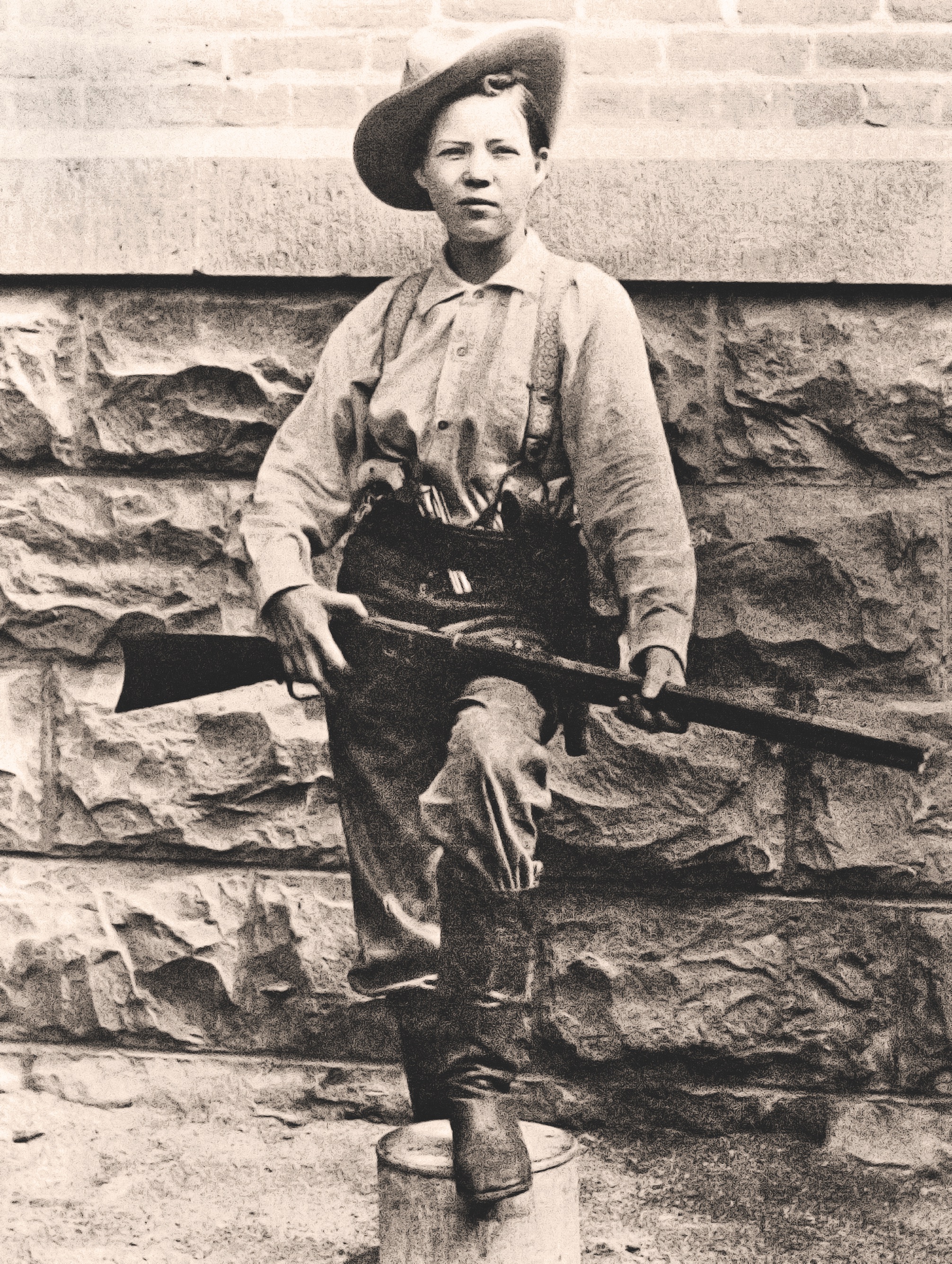

Pearl Hart was a wildcat on and off the outlaw trail.

Few Old West outlaws have had so many myths written about them as Pearl Hart, the Arizona stage robber. Despite the legends, Pearl, unlike almost every notorious woman of the Old West, was a real frontier bandit. For the last hundred years, misinformed Western writers have featured a plethora of purported female Western desperadoes. However, few of these “wild women” were outlaws. Annie Oakley was a sharpshooter and performer, not a criminal. Calamity Jane (true name Martha Jane Canary) claimed to have been a U.S. Army scout, but in fact she was a frontier prostitute and camp follower. Eleanor Dumont, better known as Madame Moustache, was a Western gambler, not a desperado. Many writers have claimed that Belle Starr (1848-89) was a frontier robber, and she is known today as the Bandit Queen of Oklahoma. In fact, Belle Starr was primarily a consort of outlaws. Although she was once convicted of horse theft, she never robbed anyone.

Pearl Hart’s true story has been long lost in the mists of the past. Her real name, her real background, and her real adventures have been lost and replaced by folklore and fiction. But today, genealogical data banks and digital newspaper sites have provided the key to unraveling the facts of her life. She was born Lillie Davy in Lindsay, Ontario, Canada, in 1871, and raised by an abusive, rapist father and a kindly but badly abused mother. Several times she and her younger sister ran away from their troubled, impoverished home, hopping freight trains and dressing as boys to ward off unwanted sexual advances. There was no social safety net in that era, so Lillie and her sisters, all physically attractive, turned to prostitution for survival.

Arizona-Bound

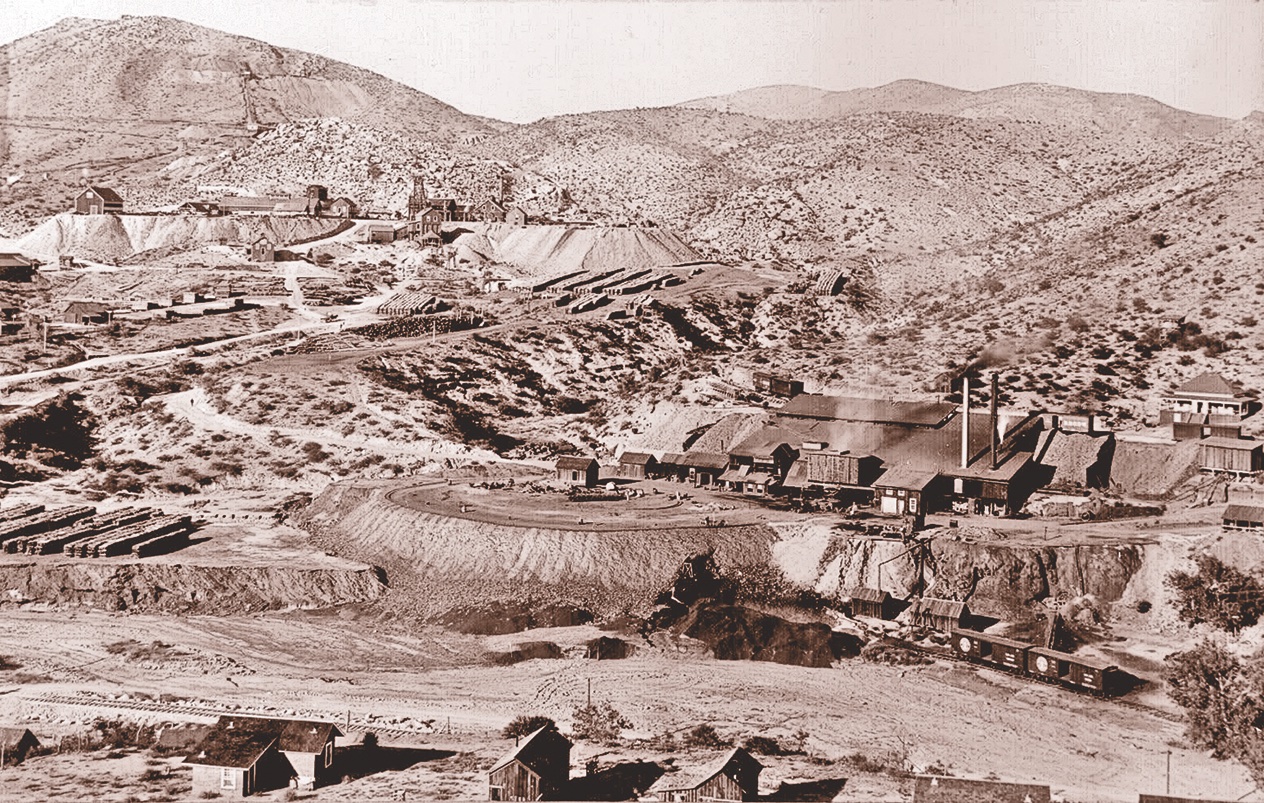

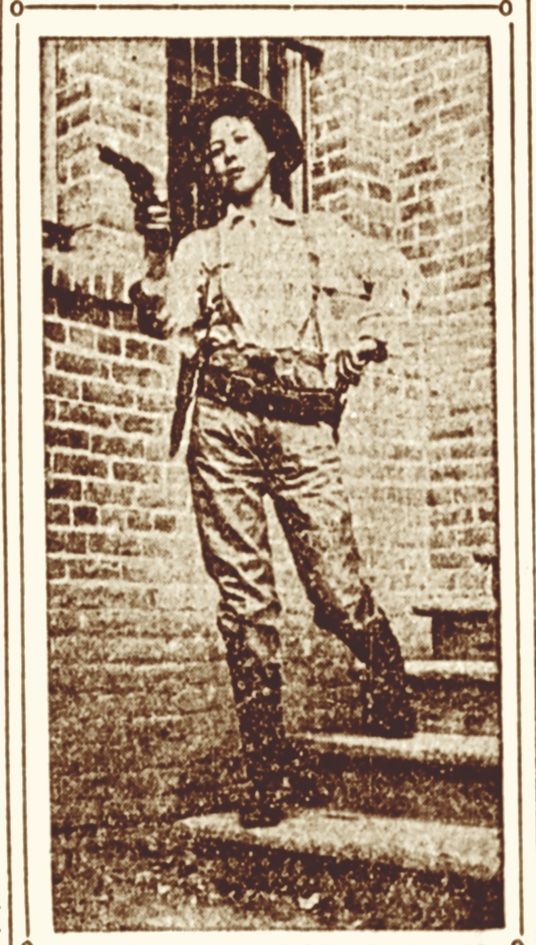

After many misadventures, Lillie married an abusive, morphine-addicted piano player named Dan Bandman. In 1893 she fled her violent husband and went west. In 1894, Lillie landed in Arizona Territory, where she adopted the alias Pearl Hart and found work in brothels in Tucson and Phoenix. She later said that she came up with the idea of robbing a stagecoach in order to get enough money to return to her mother in the Midwest. Pearl teamed up with an out-of-luck miner named Joe Boot. They procured horses, guns and supplies and rode out of the mining town of Globe in late May 1899. Pearl dressed like an Arizona cowboy, with wide-brimmed hat, men’s knee boots, six-shooter and rifle.

The two rode through Pioneer Pass, then descended into Kane Spring Canyon. According to a journalist of the day, “The road at that point is one of the worst in the Southwest, following the bed of a creek.” The trail was steep and skirted high cliffs. Finally Pearl and Joe rode into Riverside, on the Gila River. It was a small settlement with a stagecoach stop and a population of about 50. Nearby, they made camp and watched the coaches as they came in and out of the station. Pearl and Joe soon figured out the stage schedule and learned that Wells Fargo guards did not regularly ride the road from Globe. That was good news, for only a very daring or very stupid bandit would tangle with a Wells Fargo shotgun messenger.

Several townsfolk spotted the two strangers in Riverside, and one of them later said that the holdup plan originated with Pearl, not Joe. The witness overheard them discussing a possible robbery, and Boot declared, “I can never do it. Never, never, never!”

“But you must—we must!” she insisted. “And it’s easy. All you’ll have to do will be to hold your gun out straight and keep quiet. I’ll do the rest.”

The Robbery

On May 29, 1899, the pair rode out of their camp near Riverside, splashed their horses across the Gila River, and headed back to Kane Spring Canyon. Pearl later told the story:

“On the afternoon of the robbery we took our horses and rode over the mountains and through the canyons, and at last hit the Globe road. We rode along slowly until we came to a bend in the road, which was a most favorable spot for our undertaking. We halted and listened till we heard the stage. Then we went forward on a slow walk, till we saw the stage coming around the bend. We then pulled to one side of the road. Joe drew a forty-five, and said, ‘Throw up your hands!’ I drew my little thirty-eight and likewise covered the occupants of the stage. Joe said to me, ‘Get off your horse.’ I did so, while he kept the people covered. He ordered them out of the stage. They were a badly scared outfit. I learned how easily a job of this kind could be done.

“Joe told me to search the passengers for arms. I carefully went through them all. They had no pistols. Joe motioned toward the stage. I advanced and searched it, and found the brave passengers had left two of their guns behind them when ordered out of the stage. Really, I can’t see why men carry revolvers, because they almost invariably give them up at the very time they were made to be used. They certainly don’t want revolvers for playthings. I gave Joe a forty-four, and kept the forty-five for myself. Joe told me to search the passengers for money. I did so, and found on the fellow who was shaking the worst 390 dollars. This fellow was trembling so I could hardly get my hand in his pockets. The other fellow, a sort of a dude, with his hair parted in the middle, tried to tell me how much he needed the money, but he yielded 36 dollars, a dime and two nickels. Then I searched the remaining passenger, a Chinaman. He was nearer my size, and I just scared him to death. His clothes enabled me to go through him quickly. I only got five dollars, however. The stage driver had a few dollars, but after a council of war, we decided not to rob him.”

Good-Hearted Bandit

Pearl gave another account in which she provided more details:

“When the coach came in sight we rode down into the canyon to meet it. Our masks were lost in going to the camp, but we didn’t mind that. So on we rode. As we came upon the coach the driver reined his horses to have a word with us, as travelers out there do, and as the three passengers stuck their heads out to see why the stop was made, we covered them and ordered all four men to line up outside. While Joe kept their hands up at the point of the Winchester, I searched the men. I had to pull off one of my gloves to do this, and in this way the men saw by my hand that I was a woman. I can still see the Chinaman, who was one of the passengers, holding our horses. He was smiling at the thought that he was so kind we would not rob him. You can bet he was smiling on the other side of his face when I was through with him. I left about two dollars for each man, and told them to continue their journey and not to look back under penalty of being shot.”

Pearl later claimed that, after returning the driver’s money, she told him with a laugh, “You may keep that. I believe you’ve earned it by driving three such cowards across the hills.”

Pearl added that after giving a few dollars back to the passengers, she told them, “Being a good fellow, I kind of hate to see folks dead broke, so I’ll stake you all. And now take a run back along the trail for the good of your health.”

Then, watching the stagecoach disappear down the canyon, she exclaimed, “Come on, Joe!” The two then walked to the spot where their horses were tied, mounted up and rode off.

Pearl’s account was reasonably accurate and differed slightly from the details later provided by the stage driver, his passengers and lawmen. She and Joe set up their ambush at a spot in Kane Spring Canyon that was four miles from the Gila River. It was a narrow, twisting bend where the driver could not see more than twenty feet ahead of his lead horses. The outlaws waited for three hours for the coach to arrive. It was five p.m. when the stage from Globe came rattling down the rough trail. It was not a large, six-horse Concord coach of the type commonly seen in television and film. Instead the stage was a much lighter conveyance that looked like a carriage, known as a “mud wagon.” It had three seats, a canvas top, and a four-horse team. At the “ribbons,” or reins, was stage driver Henry Bacon. He had three passengers: Oscar J. Neil, a traveling salesmen; an old man named Harding; and a Chinese passenger whose name was never recorded. Pearl and Joe stepped out from the roadside brush and Joe called out, “Halt!”

Bacon pulled back on the reins and quickly set his brake.

“Climb out of there!” Joe barked. The driver and passengers meekly complied, even though Bacon and Neil were armed with large revolvers. Pearl and Joe lined the four men up and went through their pockets. From Neil they took 390 dollars, his pistol and a gold pocket watch worth 50 dollars. Henry Bacon coughed up his six-gun and eight dollars, but Pearl handed the money back to him. They relieved the Chinese passenger of 30 dollars. The bandits took 40 dollars from the other passenger, Harding. However, before climbing out of the stage, Harding had slipped into his mouth a tobacco pouch holding 80 dollars in gold. A journalist who later interviewed the passengers wrote, “He presented a ludicrous appearance with his cheeks swelled out and the strings of the pouch hanging from his lips. The highwaymen failed to notice it, however.”

Joe Boot did most of the talking, probably because Pearl did not want her voice to reveal that she was a woman. The only words she actually spoke were to one of the passengers who was slow in handing over his cash. Pearl barked, “Cough up, partner, or I’ll plug you.”

After completing the search, Pearl handed back four silver dollars to each of the victims. The passengers later said that they were convinced that “the smaller of the two robbers was a woman. Her figure had only been illy concealed by the crude garb she wore of rough shirt and blue overalls, the latter tucked into coarse boots that were plainly far too large. Under the dirty cowboy hat…there showed a curl or two of dark hair, and the hands that had deftly turned their pockets inside out were small and white.”

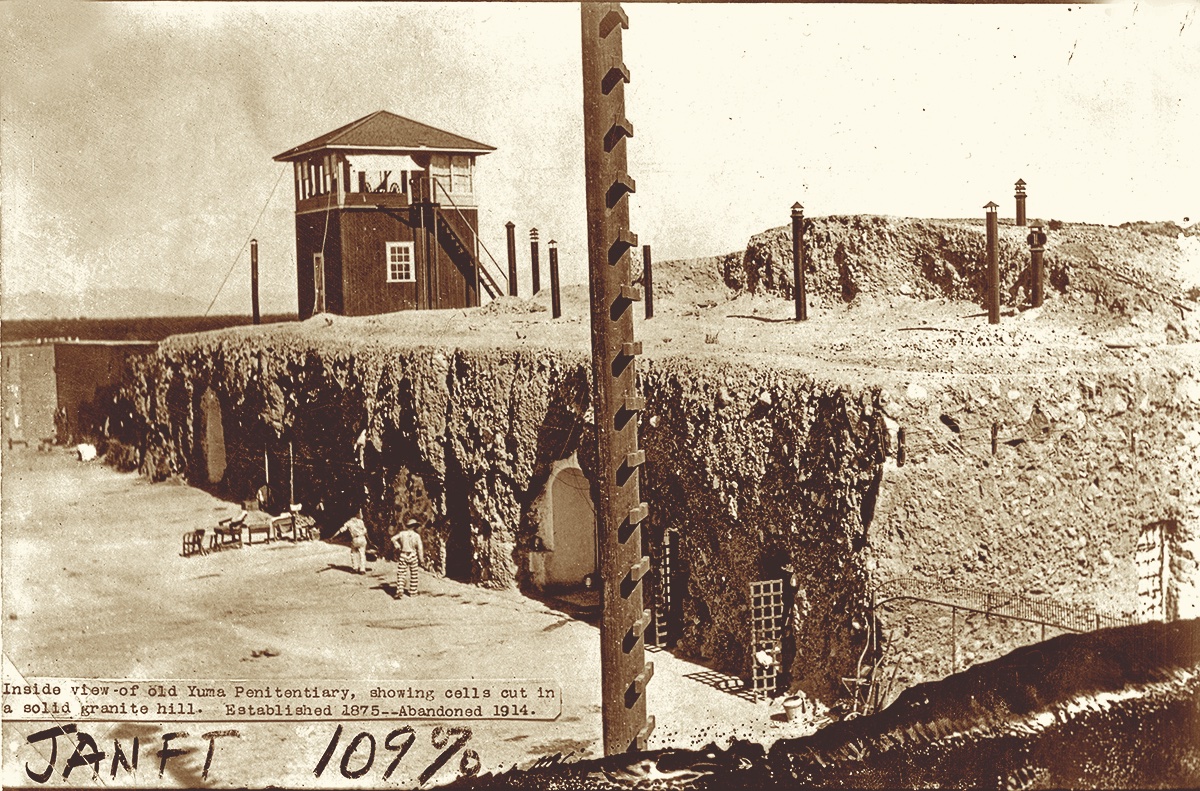

Joe then ordered the men back into the stage. Henry Bacon whipped up his team, and the coach lurched off toward Riverside. Pearl and Joe then mounted their horses and fled south, headed for the Southern Pacific railroad. A sheriff’s posse was soon in pursuit. The lawmen managed to capture the pair after a long manhunt. The case made newspaper headlines throughout the country, for a woman stage robber was unheard of. Pearl soon broke out of jail, was recaptured after another manhunt and became the most famous convict ever lodged in Yuma prison. Thus began even more adventures for Pearl Hart—but that is another story.

In an era when a woman’s role was domestic—cooking, cleaning, working on the family farm, raising children and attending church—Pearl Hart violated every one of society’s taboos. She swore, smoked, drank, robbed, rode hard, broke jail and used men with abandon. The Old West never saw another woman like her.

John Boessenecker has studied and written about the history of outlaws and lawmen of the Old West for more than 50 years, and has authored books and dozens of magazine articles on the subject. “A Real Woman Bandit: Pearl Hart was a wildcat on and off the outlaw trail” is an exclusive excerpt from his new book, Wildcat: The Untold Story of Pearl Hart, the Wild West’s Most Notorious Woman Bandit (Hanover Square Press, 2021).