— Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell —

One of my favorite photographs of rock ’n’ roll frontman Tom Petty was taken on March 10, 1977, by Michael Putland. The singer, clad in a striped jacket over a black Heartbreakers T-shirt, neck wrapped in a scarf, blond hair to his shoulders, had his arms outstretched across the top of a couch and, above him, was an iconic Charles M. Russell painting, When Horseflesh Comes High.

Russell painted this oil in memory of a time when Stuart’s Stranglers, led by Granville Stuart, a former ranch boss of his, rode Montana’s Judith Basin range during the 1880s to track down and kill horse thieves. Russell’s romantic view focuses on the thieves, barricading themselves behind the stolen horses, as the vigilantes ride up on them.

The way cowboys feel about horses is how Petty felt about his guitars. So you can imagine the gut punch he experienced when his 1967 blond Rickenbacker 12-string was stolen in 2012 by a private security guard while the Heartbreakers band was rehearsing at a studio in Culver City, California, for an upcoming concert. Petty didn’t have to rely on vigilantes to recover his stolen property; the cops found and returned the singer’s Rickenbacker and his band’s other four guitars.

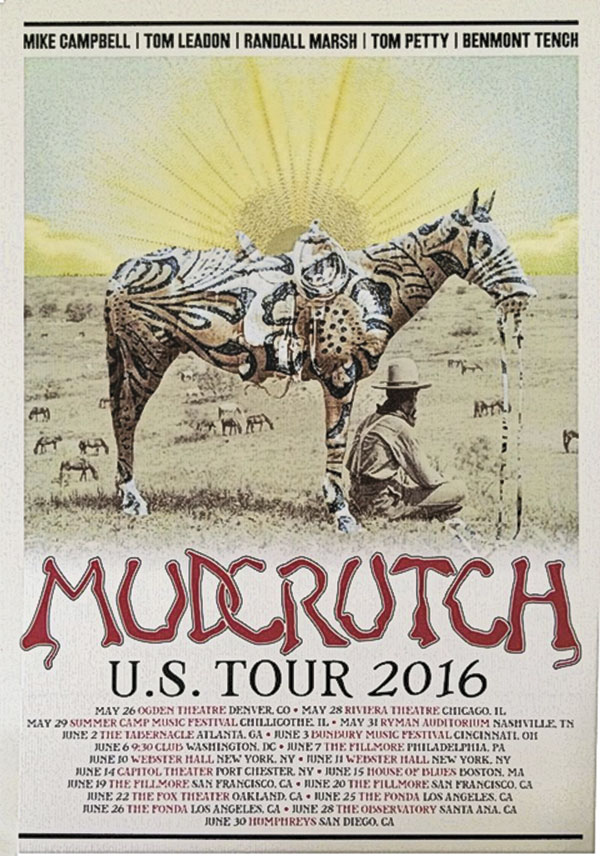

— Designed by Ryan Corey for SMOG Design, courtesy Mudcrutch —

Petty remembered the first time he heard the unique tone of that guitar, on the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night album, released in 1964. “I didn’t know what it was, you know…. So I asked at the local music store what makes that sound, and they said, ‘Hey, that’s the Rickenbacker 12-string,’” Petty told Tony Bacon, author of the 2010 book Rickenbacker Electric 12-String.

The first one Petty got, in the 1960s, differed from the 360 that got stolen; instead of triangle markers, with 12 strings, the 330 had dot markers, with six strings. The blond one that was stolen, he got in 1980. “That’s one of the best ones I have,” he told Bacon. “I have a pretty good collection of Rickenbackers that I’ve gotten over the years…. It was just always a very good American-made guitar, you know?”

The first person Petty saw with a guitar was a cowboy. Country music pioneer Ernest Tubb and Singing Cowboy Roy Rogers may have been Petty’s first touchstones before he heard tunes by Elvis, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones that would lead him to leave his own indelible mark on music, Andrea M. Rotondo noted in the biography, Tom Petty: Rock ’n’ Roll Guardian.

“When I was really young, I liked cowboys who played guitar. That’s why I thought the guitar was cool. The guitar just always seemed like a rebellious instrument to me. And then Elvis came along, [and] he was kind of like a cowboy too,” Petty told Rotondo, who has followed the singer’s career since the Heartbreakers’ debut in 1976.

Petty had long been a fan of cowboys and Indians. His paternal grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee, and family lore states his white-guy grandfather got in a fight over a racist slur directed at him and killed a guy, so the family fled from Georgia to Florida. Petty grew up in Gainesville, and from elementary school on, he was “just obsessed with Westerns,” Rotondo wrote.

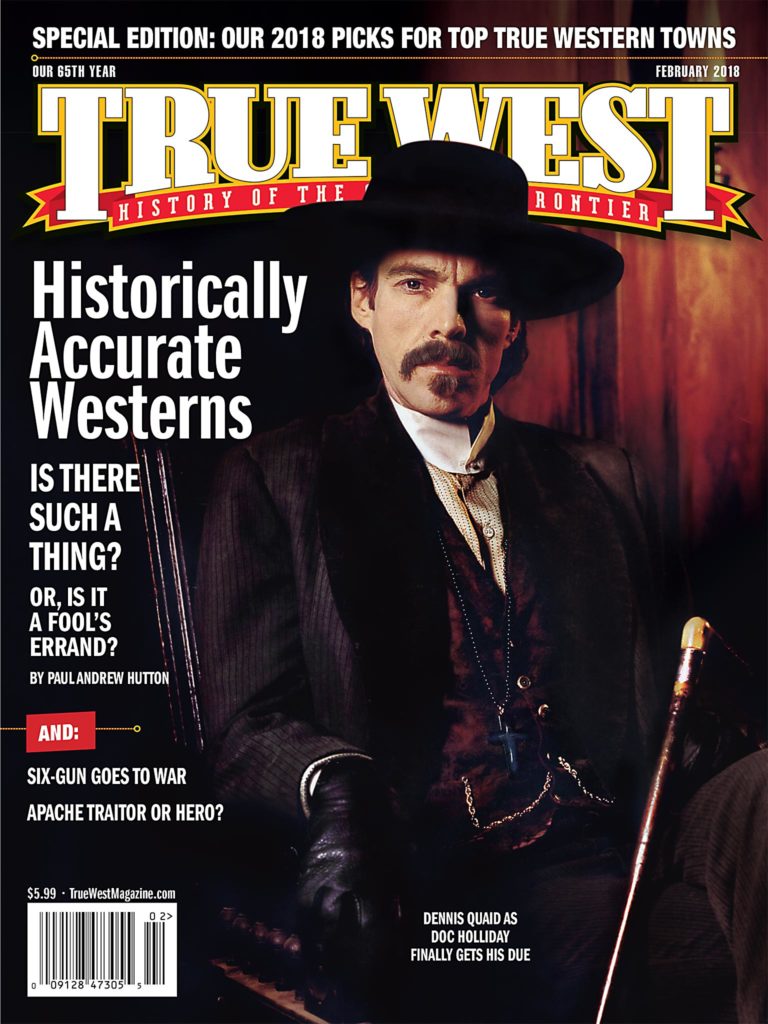

So Peter Bogdanovich found a willing audience in Petty during 2007, when the director screened classic Western movies every single day while shooting his documentary about Petty and the Heartbreakers.

Anyone who’s seen the four-hour documentary, which Variety called as smooth as “well-aged whiskey,” may recall Bogdanovich slipping in a clip from 1959’s Rio Bravo showing Ricky Nelson and Dean Martin crooning “Get Along Home, Cindy.”

Bogdanovich is a lifelong Howard Hawks fan, and his conversation with Walter Hill, Angie Dickinson and John Carpenter was featured on the remastered double disc released by Sparkhill. Coproducer Bernadette Bowman told True West, “People really love this movie. Peter Bogdanovich told me that whenever he and Tom Petty get together and Rio Bravo is on TV, they turn it on, and the world stops for them.”

Fans of Petty’s music have certainly come across his fondness for cowboy culture in Petty songs flavored by the frontier experience. Some of the ones that stand out include: “Billy the Kid” (“Did you smile when you pulled the trigger?… I went down hard, like Billy the Kid”); “About to Give Out” (“I’m Davy Crockett in a coonskin town”); “Rebels” (“With one foot in the grave and one foot on the pedal”); and “Scare Easy,” heard over the end credits of the 2008 Western Appaloosa.

At least one good song came out of one bad Western: “Two Gunslingers,” which Rolling Stone included in the magazine’s list of the 50 greatest Petty songs, was inspired after a friend jokingly gave Petty a movie poster for the terrible 1967 Western flick Hostile Guns.

When Petty worked with Dave Stewart from the Eurythmics on the band’s breakthrough song, “Don’t Come Around Here No More,” he found someone to dress cowboy with him. “Truth of it was that Dave was one of the only bright lights in that period. He was sober and funny and crazy. And quite a dresser. Each day he’d arrive in a different outfit. I remember the two of us going to a rodeo tailor and buying expensive cowboy boots and hats, just wearing these clothes and hanging around town. He kept things lively,” Petty wrote in the book based on the documentary, Runnin’ Down a Dream: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.

— Courtesy Herb Pedersen —

We all know that Petty’s “Free Fallin’” good girl was crazy ’bout Elvis, like the singer himself, and she loved horses too. Petty brought a horse from the frontier into a promotion of Mudcrutch, Petty’s band formed in 1970 before the Heartbreakers. The 2016 reunion tour poster featured a psychedelic take on a classic Erwin E. Smith photograph of a cowboy with his horse, overlooking his herd.

The singer followed up with a 40th anniversary tour with the Heartbreakers. After completing three shows at the Hollywood bowl on that tour, 66-year-old Petty died of cardiac arrest, on October 2, 2017.

An enduring everyman hero, Petty has gone to the other side of the mountain. Like so many of his fans, we’re over here missing him today. We’d love to grab that rocky ridge and get him back.

Tribute to Tom Petty

Legendary musician and lover of the Old West.

My relationship with my friend Tom Petty began when he and his bandmates in the group Mudcrutch started recording their second album, Mudcrutch 2, in Malibu, California, in September 2015.

This band from Gainesville Florida, consisted of Petty’s boyhood friends Mike Campbell, Randall Marsh, Benmont Tench and Tommy Leadon. Leadon called me one day to ask if he could borrow a five-string banjo to use on his song “The Other Side of the Mountain.” I told him, “Sure, come on over and pick one out for you.”

After trying three or four of my banjos, he decided that I was the one who should play on the recording, not him.

He called Petty, and he agreed, so I ended up playing banjo on the song and singing harmony parts on a few other tunes in the project. That led to Petty asking me to join the band on the Mudcrutch tour scheduled for June 2016.

During our travels, Petty and I became close, frequently discussing classic Western movies (one of his favorites was the John Wayne classic The Searchers) and true tales of the Old West. Each night after our show, we’d board our plane and continue our talks about the historical Southwest, never tiring of anything “cowboy.”

When the tour ended, I gave Petty a subscription to this wonderful magazine, True West. Because of his star status, we picked an anonymous name so as not to create mailing infringements. When he got his first copy in the mail, he quickly called me and said, “Hey Herb, I don’t deserve this, thank you so much.”

Petty was deserving of so much more, believe me. His kindness, great sense of humor, not to mention his tremendous talent will be missed by all of us. Happy trails, compadre.

— Herb Pedersen