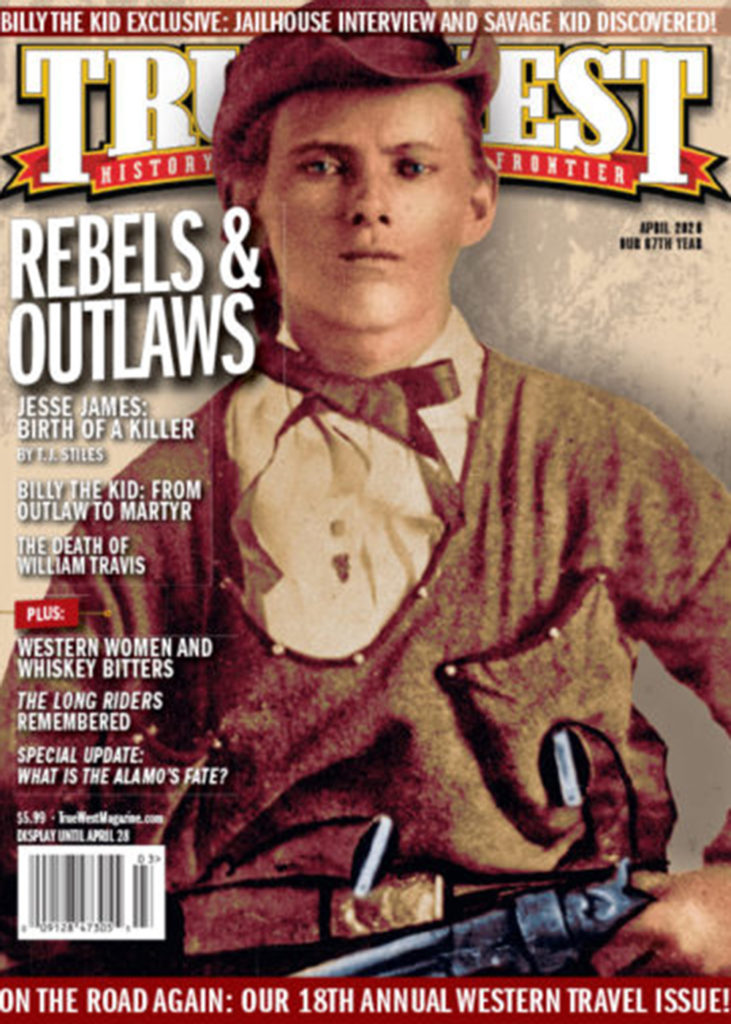

In the past year the latest Billy the Kid movie, The Kid, was produced and released, while in 2019-’20, at least three Billy the Kid biographies, two Pat Garrett bios, a Jesse James biography and four Wyatt Earp-Cowboy-Doc Holliday chronicles will hit the bookshelves. This does not even include the unknown number of Billy, Jesse and Wyatt novelizations (including Johnny D. Boggs’ recent novel

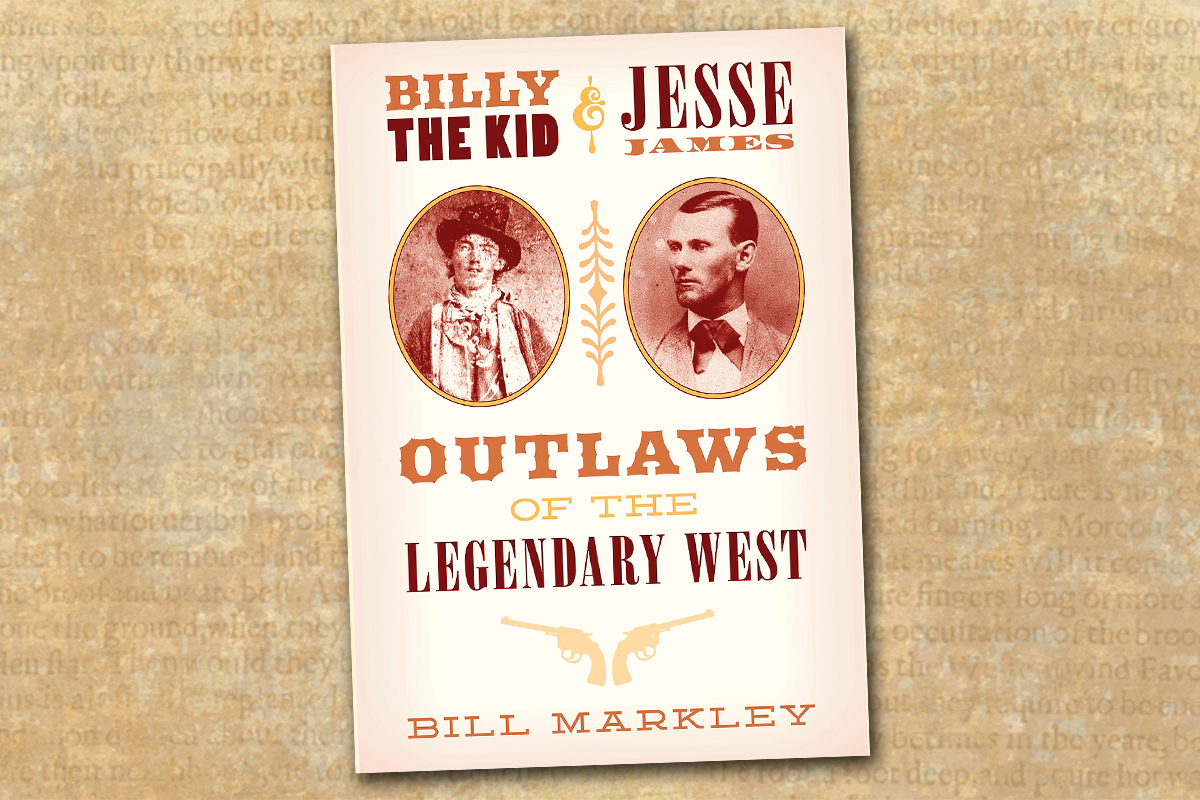

on Cole Younger and Mark Warren’s third volume in his Wyatt Earp series reviewed below), published articles and cinematic-television-streaming reruns and homages to the dynamic duo of Old West bushwhacking and banditry. Included in that barrage of entertainment and endnotes is Bill Markley’s ambitious dual biography Billy the Kid & Jesse James (TwoDot, $16.95).

Anyone who loves Old West history will enjoy the Western novelist-historian’s easy-to-read style, his sense of place, his ability to present the facts and his seemingly uncynical perspective about the ongoing debates that swirl around the two outlaws. He willingly admits, “[A]fter studying Jesse James and Billy the Kid, I’ve come to view them both as like- able criminals. They could be pleasant company and they enjoyed a good joke.” I’m not so sure their victims would share such breezy character analysis of the two killers, but Markley remains in good company with millions of Jesse and Billy fans.

Billy the Kid & Jesse James is the second volume in the South Dakota author’s Outlaws of the Legendary West series with TwoDot. Markley’s dual biography is written—like his first, Wyatt Earp & Bat Masterson—in a popular narrative style that is highly accessible to a broad audience seeking a strong introductory biography of the two legendary outlaws. Markley does not necessarily uncover new primary material or sources on Jesse or Billy, but he provides an excellent paper trail of his sources in his endnotes and bibliography. Readers also will enjoy Jim Hatzell’s original illustrations. He relies heavily on the best-of-the-best modern Jesse and Billy biographers (all of whom—Bob Boze Bell, Johnny D. Boggs, Richard Etulain, Mark Lee Gardner, Paul Andrew Hutton, Fred Nolan, T.J. Stiles and Robert Utley—are excerpted or quoted in this issue) and makes no apologies for it. Markley is an excellent synthesizer of secondary sources and knows his audience.

If you finish the intrepid historian’s Billy the Kid & Jesse James and aren’t excited enough to immediately rush out to buy the best monographs by the aforementioned historians—and then go and re-watch film and television interpretations of the fabled killers—then you have completely missed the point of Markley’s biography of the mythologized bandits: “Jesse James and Billy the Kid will continue to ride across the landscape of America’s imagination, always on the run—never to be caught.”

So get out there: hit the hoot-owl trail to see what more you can discover about these long-dead scurrilous characters and try to figure out why we celebrate two cold-blooded killers as American heroes.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Editor’s Note: Love Western travel? Read frequent True West contributor Bill Markley’s article “Black Hills Gold.”

Gang Warfare in Texas

David Johnson is one of the most important chroniclers of Texas hardcases, with books on the Horrell family, John Ringo and the Mason County/Hoodoo War. In his latest, Johnson takes on one of the most violent gangs in the history of the Lone Star State. The Cornett-Whitley Gang: Violence Unleashed in Texas (University of North Texas Press, $29.95) tells about an outfit that is little remembered today. Yet, between 1886 and 1888, the bandits made lots of headlines. They took lots of loot, but they tortured express messengers and pistol-whipped innocent passengers. People feared them. The law was determined to bring them down (and did). As always, David Johnson’s work is well-researched and well-told.

—Mark Boardman, True West features editor

A Man with a Badge

Much has been documented about Wyatt Earp’s career, but in Promised Land: Wyatt Earp: An American Odyssey, Book 3 (Five Star Publishing, $25.95) author Mark Warren delves into the lawman’s character. Woven with clarity and colorful prose, Warren takes readers on an odyssey to 1879 Tombstone where we feel the desert dust and hear the jangle of spurs as Wyatt and his band of brothers patrol the streets in their iconic black greatcoats. An accomplished researcher, Warren is ever-faithful to the facts while reverently imagining thoughts and dialogue for these historical figures. Warren blogs, “This is why I waited 60 years to write about a fearless man. It took me that long to understand what made Wyatt Earp tick.” Readers will learn more intimately about Earp’s code of straightforward behavior, thanks to Warren’s artistry and dedication.

—Denise F. McAllister, owner of McAllisterEditing.com

The Snake’s Ugly Head

Jack Slater (Wolfpack Publishing $14.99) by Johnny Gunn centers around the corruption of the local government politics in Elko County, Nevada, during the late 1800s. Gunn’s villain Luke Pardee wants to control elections and the government of Elko County through money and physical threats but is confronted by Jack Slater. Gunn takes readers through one danger after another as Pardee tries to retain control by eliminating Slater’s family and anyone who is against him. Readers will be kept wondering what will happen next until the end. I enjoyed reading Gunn’s novel, finding that it could be applied to modern-day politics.

—Lowell F. Volk, author of the Luke Taylor and Trevor Lane series

Massacre Versus Genocide

Arguably, from the appearance of Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor in 1881, followed three years later by J.P. Dunn’s Massacres of the Mountains, generations of writers have wrestled with the treatment of American Indians in the United States. Jeffrey Ostler’s Surviving Genocide: Native Americans and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas (Yale University Press, $37.50) is among the most recent entries into the ongoing and unresolved issue and is the first of a two-volume study. As indicated by the title, the interpretation draws heavily on the term Raphael Lemkin coined in his 1944 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, and which, in many respects has displaced the older, oft used idiom “massacre.” Whether Professor Ostler succeeds in making a convincing case remains a question to be answered by the reader.

—John Langellier has spent over a half century in the study of the so-called Indian Wars