– Colorado River Photo by Timothy O’Sullivan Courtesy Library of Congress –

Not long after his graduation from West Point, Lt. George M. Wheeler became an assistant survey engineer in the San Francisco area. Promoted to first lieutenant on March 7, 1867, he became an engineer for the Department of California. This set Wheeler on a course surveying and exploring. A year later, he named the Colorado Plateau—a region encompassing portions of southwestern Colorado, western New Mexico, eastern and southern Utah and northeastern Arizona.

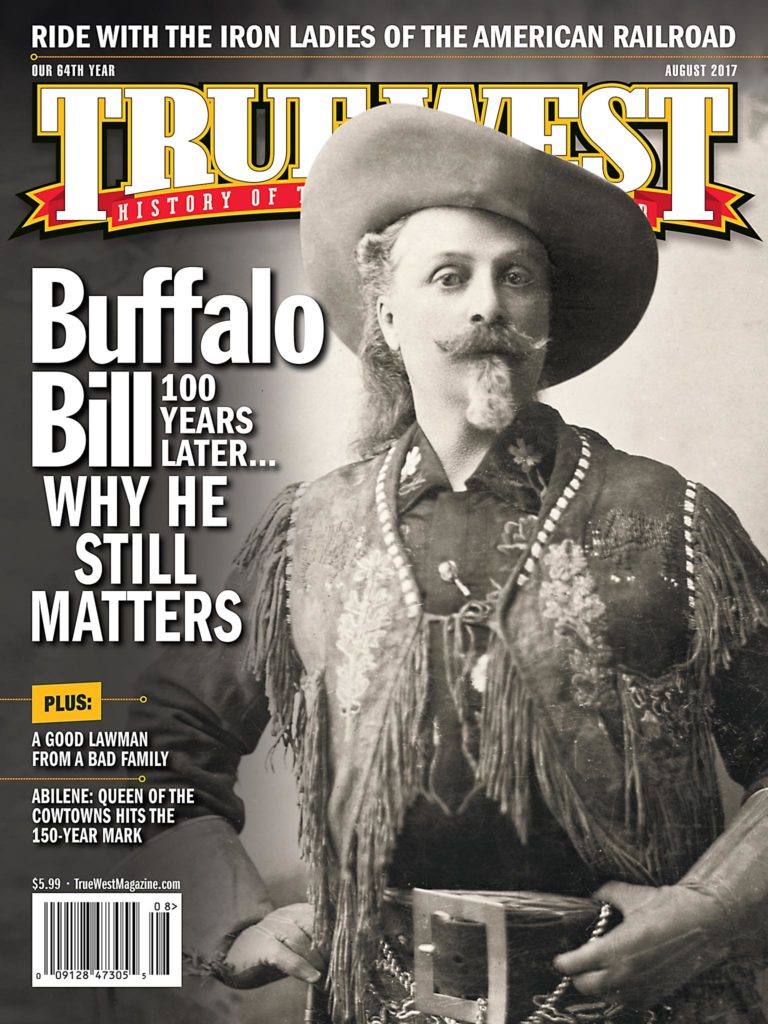

– Portrait of George Wheeler by Alice Pike Barney Public Domain @ AmericanGallery.Wordpress.com –

Four great surveys of the American West were underway—or began—in 1869. That year John Wesley Powell pushed off from Green River, following the Green and Colorado rivers downstream, Clarence King was in Utah, Ferdinand V. Hayden moved into Wyoming, and George Wheeler surveyed some 24,000 square miles of southeastern Nevada and Utah.

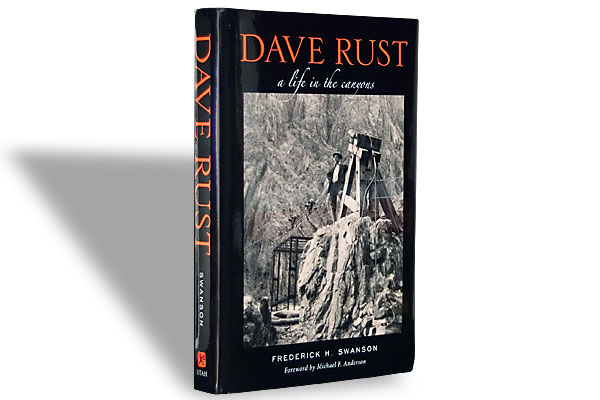

Their work would overspread the West in ensuing years. Wheeler left San Francisco in the spring of 1871, traveling to Halleck Station, near Elko, Nevada, where he assembled his men including photographer Timothy H. O’Sullivan who would travel often with Wheeler, capturing scenes of the survey party at work, the landscape and the indigenous people of the region.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

71,250 Miles and Counting

During 1871 Wheeler’s team surveyed an astounding 71,250 miles, covering central, southern and southwestern Nevada, eastern California, southwestern Utah, and northwestern, central and southern Arizona. While Powell was again on the Colorado River exploring the Grand Canyon, Wheeler also headed in that direction. He had flat-bottomed boats delivered to Camp Mohave at the California border, where he put in and headed upriver on the Colorado.

Wheeler reached Black Canyon, Bolder Canyon and went as far as Diamond Creek before halting his explorations.

Our route begins in Death Valley National Park, a landscape Wheeler’s surveys covered, and a place that demonstrates some of the difficult climatic conditions the surveyors experienced. Traveling east to Las Vegas, Nevada, visit Springs Preserve, site of the original natural spring that led to the establishment of this community. Then, midway between Las Vegas and Mesquite, visit the Valley of Fire with its plethora of petroglyphs and pictographs.

Depart Nevada and head into southern Utah, traveling through St. George and Zion National Park to Kanab, just north of the Arizona border. For his second expedition in 1871-’73, John Wesley Powell made his headquarters in the Mormon pioneer community of Kanab. The town is also known as “Little Hollywood,” as it’s been a favorite location for filmmakers since Tom Mix made Deadwood Coach in 1924. Go south on U.S. 89A and west on Arizona 389 across the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians Reservation for a visit to Pipe Springs National Monument, a historic cultural crossroads settled in the 1860s by Mormon ranchers from St. George. Visitors can tour the pioneer settlement, including the 1870s-era fort, and the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians Visitor Center and Museum.

Reversing travel from Pipe Springs, drive east and then south across the Kaibab Plateau toward Jacob Lake and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. More remote and less visited than the South Rim, this vast, lightly populated area, also known as the Arizona Strip

(the land north and west of the Grand Canyon adjacent to Utah and Nevada), is

representative of the landscapes Wheeler’s party surveyed. You can continue on U.S. 89A to Page, Arizona, or return to U.S. 89 for a circuitous multi-day route through southern Utah to visit Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Capitol Reef National Park and Natural Bridges National Monument—before arriving at Monument Valley on the Utah-Arizona border.

– Courtesy Utah Office of Tourism –

Arizona’s Canyonlands

At Page, Glen Canyon Dam backs up the Colorado River, forming Lake Powell. This reclamation project forever changed the river’s ecosystem above and below the dam, by flooding canyons and making sites such as Rainbow Bridge accessible by bridge or overland on Navajo-led guided expeditions. Slot canyons, such as Antelope Canyon and Canyon X, are great places for visitors to explore and immerse themselves in this remarkable landscape.

From Page, travel south on U.S. 89 to U.S. 160, which goes east to Tuba City, the gateway trading post community to the Navajo and Hopi reservations, or you can continue south and west to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. I head east on U.S. 160 to Navajo National Monument and Kayenta. Here, make a detour on U.S. 163 into Monument Valley, a place immortalized in films ranging from John Ford classics to Forrest Gump. My route continues south on U.S. 191 to Chinle, Arizona, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. This is truly one of the special and sacred places on the planet. I headed into the monument on horseback, crossing and recrossing Chinle Wash, listening to stories shared by a Navajo guide, staring awestruck at the massive rock face of the canyon walls. Later, a vehicle trip along the rim of the canyon provided a different view—equally inspiring and culturally enriching.

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

After exploring Canyon de Chelly, my route on U.S. 191 continues south to Arizona 264 and east to Hubbell Trading Post, a business enterprise in Ganado that has been selling to travelers and residents since 1878. After Ganado, continue south to Gallup, New Mexico, near the site of Fort Wingate, where one of Wheeler’s exploring expeditions spent time resting after six weeks of surveying. Then I travel north on U.S. 491 past the landmark rock formation Ship Rock to Shiprock, New Mexico, and U.S. 64 to Teec Nos Pos, Arizona, just south of the Four Corners Monument, because what trip to this area of the country is complete without standing where you can at least see four states? The idea that standing at the bronze marker within the relatively commercial plaza at Four Corners means you can actually touch the four states at one time, is just that—an idea. Since the marker has moved more than once, it undoubtedly is not at the actual point where the states meet.

– Gates Frontiers Fund Colorado Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress –

Colorado’s Canyons of the Ancients

From Four Corners I head north into Colorado on U.S. 160, traveling across the Ute Mountain Tribe Reservation to spend time in Cortez, a perfect headquarters for visitors exploring the ancient archaeological sites of Southwest Colorado—Canyon of the Ancients National Monument, Ute Mountain Tribal Park and Mesa Verde National Park. After Cortez, I drive east across the San Juan Mountains on U.S. 160 to Fort Garland in the San Luis Valley.

In 1872, Wheeler was authorized by Congress to direct the United States Geological Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian, a seven-year project that would be known as the Wheeler Survey. The survey’s main goal was to make topographic maps of the southwestern United States. Also, Wheeler was charged with identifying the physical

features of the region; discovering the numbers, habits and disposition of Indians in the section; selecting sites for future military installations; determining routes for rail lines and roads; and making notes about mineral resources, climate, geology, vegetation, water sources and agricultural potential.

– Courtesy San Luis Valley Museum Association –

Wheeler and his team explored a vast area in 1872 and then covered another 72,500 square miles in 1873. In 1874, more organized and methodical, the survey encompassed only 23,281 miles.

In his years of surveying, Wheeler used a team of military and civilian workers, including packers, scientists, cooks, photographers, journalists and army soldiers. They had horses and mules, and wore woolen clothing and hob-nailed boots.

Among the contemporary chroniclers was William H. Rideing, a correspondent for Harper’s, Appleton’s, the New York Times and other publications. He later compiled his newspaper articles and published them in a collection titled A-Saddle in the Wild West: A Glimpse of Travel among the Mountains, Lava Beds, Sand Deserts, Adobe Towns, Indian Reservations, and Ancient Pueblos of Southern Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona.

– Courtesy Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress–

New Mexico’s Land of Pueblos

During 1875, the Morrison division of Wheeler’s group headed into Colorado, beginning their survey at Pueblo and then traveling to Fort Garland and the San Luis Valley before surveying south into New Mexico and then west into Arizona. This was a small party with just nine men and 22 mules.

Rideing described the scene at Fort Garland: “The reveille was beaten, [the] guard mounted, and relieved in the fullest and neatest dress, and to inspiring music, even though six men were all the post could muster.”

These Colorado explorations included Conejos, but in New Mexico they visited Tierra Amarilla, and then explored west into Canyon de Chelly, traveling south to Fort Wingate, before they returned to Santa Fe (a city they had skirted earlier). Rideing described the bustling square and Governor’s Palace: “Fashionably-dressed civilians, military officers in blue and gold, rough-looking soldiers, weather-beaten emigrants and broad-hatted teamsters with raw-hide whips that crack like a pistol” dominated a scene, but there also were “women who sat outside the doorways making cigarettes, pulling their shawls over their heads.”

– Courtesy New Mexico Dept. of Tourism –

In spite of the good work done and the very real prospect that Wheeler’s team could survey the entire territory west of the 100th meridian effectively, Congress had abandoned the project by 1878. Wheeler, promoted to captain that year, became despondent. He was on sick leave from the Army from 1880 until 1884. He returned to active duty in 1885 and 1886, and finally published his Geographical Report in 1881, which contained 164 maps and 41 reports. He had cited a disability and retired a year earlier, in 1888. He would live until 1905.

George Wheeler’s name lives on, however. Wheeler Peak in Nevada’s Great Basin National Park, Wheeler Peak in New Mexico and the scenic Wheeler Geologic Area in southern Colorado are named for him.

Candy Moulton is a regular contributor to True West. When not writing articles or managing the Western Writers of America, she is busy developing films and multimedia programs for museums and visitors’ centers in the West.