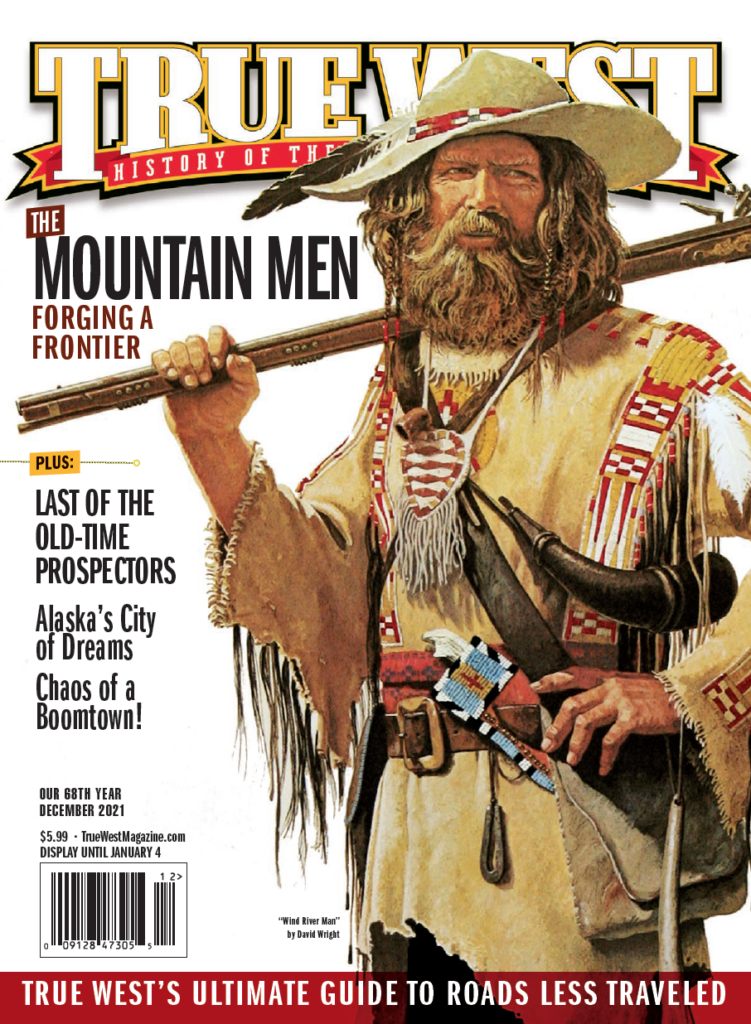

A Yankee prospector’s scrapbook of his summer in Nome reveals the hardships of the Arctic gold rush.

On a stormy May 23, 1900, Connecticut native Frank E. Downs and a group of friends steamed north from Seattle, Washington, on the SS Olympia to find their fortune in gold on the chaotic shores of the Bering Sea and Nome, Alaska. They were part of the Cape Nome gold rush that had started when three lucky Swedes discovered gold in Anvil Creek in September 1898. A few short months later, the stampede was on to the Arctic boomtown. By December, Nome had over 10,000 residents dug in for winter on the isolated southern Seward Peninsula coast of the Norton Sound. Just like those who flocked to the Klondike and Fairbanks gold rushes, which were happening at the same time, men and women by the thousands turned their backs on their homes and struck out for Nome hoping to strike it rich.

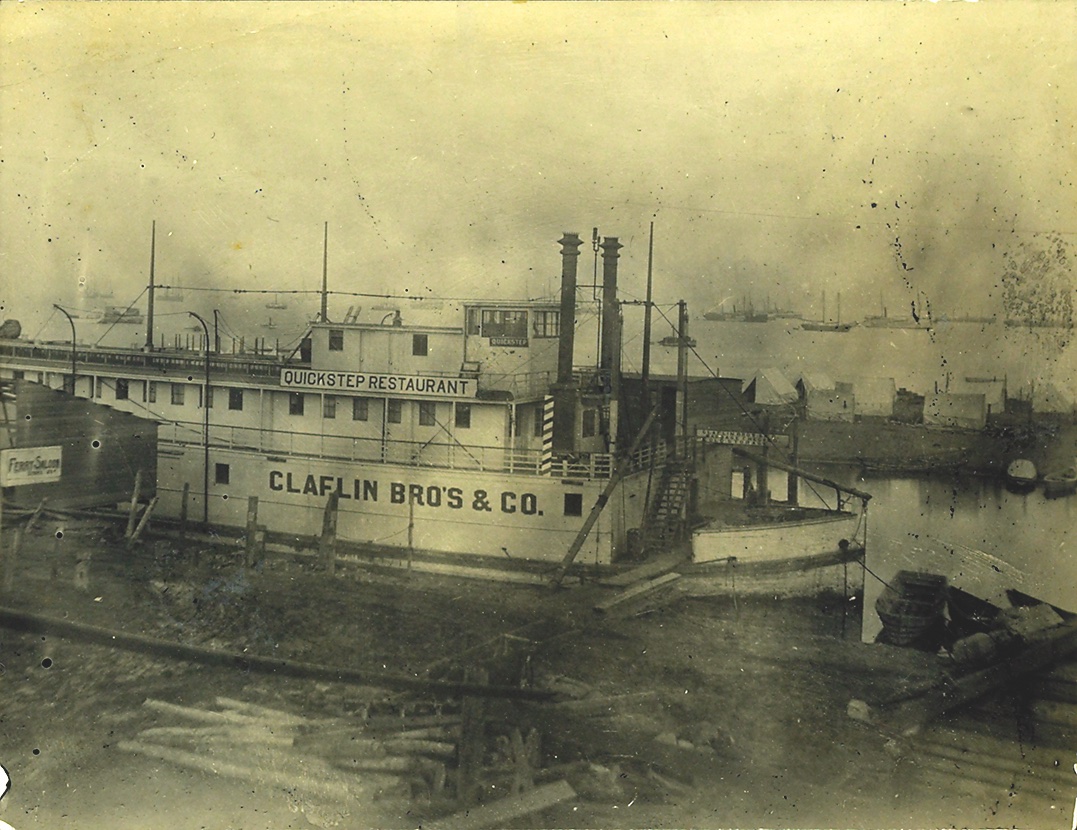

Frank Downs, the son of a prominent feed lot owner in Bristol, Connecticut, had grown up hearing stories about his Uncle Robert Carleton Downs who had gone West during the California Gold Rush and had remained in the Golden State since 1849. Likely inspired by his uncle, 43-year-old Frank went to Nome, camera in hand, and set up his tent camp and sluice on the beach four miles from the town’s center. Downs and his fellow stampeders, N. Muzzy, J.H. Pomeroy (a mining engineer), Jacob “Jake” Friedel and A. H. Buckingham, put their backs into it and worked their claims through the Arctic summer. Downs took photographs along the beach, in camp, at work, in town and even at midnight when the sun did not set. The adventurous Yankee’s images capture the rawness and hazards of living on the edge of the Arctic amidst the mud, disease, detritus and extremes of life under the midnight sun.

A major storm hit Nome on September 11-13 resulting in a great loss of life aboard ships at sea and on land, where many buildings were damaged or destroyed, as were encampments, including that of Frank Downs and friends. National newspaper reports recounted that the town’s mines were hitting bottom and many fortune-seekers were leaving because the gold was playing out. The desolation of the storm left Frank no choice: he, like hundreds of others, packed up and returned south by steamship to Seattle.

Downs’s return to the states without riches did not quell his wanderlust. He continued to tour the Western United States and Mexico, chronicling his way-stops with his ever-ready camera along the way. Following in the footsteps of another uncle, Ash Upson (well-known New Mexico journalist and co-author of Pat Garrett’s autobiography), Downs settled in the Pecos River Valley near Carlsbad Plantation and Orchards Company. Frank’s sister, Florence Emlyn Downs Muzzy, compiled the scrapbook a few years later, with unique annotations (most likely gleaned from stories told to her by her brother) that provide us with remarkable insight into the life of a prospector who had answered the call of the wild and gone north—north to Alaska!

Editor’s Note: Florence Muzzy’s daughter, Frank’s niece, Adrienne Florence Muzzy, was a librarian for the New York Public Library and was responsible for the donation of the invaluable, annotated scrapbook to the library’s special collections. Further reporting on the New Mexico connection to Frank and Florence’s famous maternal uncle, Marshall Ashman “Ash” Upson, will await another story.