The propeller boat S.P. Carter churned through the choppy waters of the Illinois River three miles below Peoria. Aboard, Capt. Samuel Gill and eight stalwarts of his city police force peered into the darkness of the September night. Glimmers flitted like fireflies off the port bow not far ahead. The captain whispered, “That’s her,” and signaled the pilot to cut the engine. Silent now but for the soft lapping of the water against her sides, S.P. Carter glided to shore some yards above the outline of a common keelboat about 50 feet long, moored to the bank. It was what the natives called a “gunboat,” familiar to the officers of the law. On the deck perched a house with four doors—one at each end, one on each side. There was no one to be seen, but gleams of light slanted through windows in the house, and the squeals of catgut and thumps of dancing feet rose and fell on the wind.

Captain Gill gathered his men around him and drew up a plan of action. With officers O’Connor, Wason and Strong at his heels, he stole along the weed-strewn riverbank and slipped aboard the gunboat, his men fanning out, posting themselves next to three of the doors. The crew of S.P. Carter, which had drifted down on the current and anchored next to the other boat, guarded the last exit. Captain Gill edged up to a window and ran his eye over the scene within, illuminated by smoky lamplight. The bar, the dance floor, the revelers, the warren of sleeping quarters—all confirmed his suspicions.

— Lithograph of Peoria, Illinois, and Sanborn Map of Peoria Courtesy Library of Congress —

For some days complaints had reached his ears about this boat tied up at Wesley Bend, beyond the city limits but by ordinance still within his jurisdiction. A young man from the lower end of Peoria had gone there night after night to carouse and then stagger home and abuse his mother; one of the denizens of the boat had marched into the uproarious Bunker Hill section of town and boldly stoned a house, settling old scores. And, as if these scenes from Donnybrook Fair were not alarming enough, intimations even more troubling to civic rectitude had become public knowledge. It would not do. In Captain Gill’s mind, the gunboat had overstayed its welcome. He put a patrol whistle to his lips and blew a sharp blast. His men charged through the four doors. The fiddler and the dancers scattered, but there was no escape. In one of the eight bedrooms, a man cursed and threw on his clothes, while the woman with him broke out in knowing laughter and told him to give up. He was well and truly caught. The police shouldered open other bedroom doors and pounced on the dazed and startled inhabitants of the floating brothel. Among them were the owner, an experienced pimp from Beardstown, 90 miles downriver, and in another room the owner’s bartender and right-hand man, a rough-house slugger named Wyatt Earp, who’d brawled his way through the tie camps of the transcontinental railway a few years earlier, and Earp’s wife, Sarah.

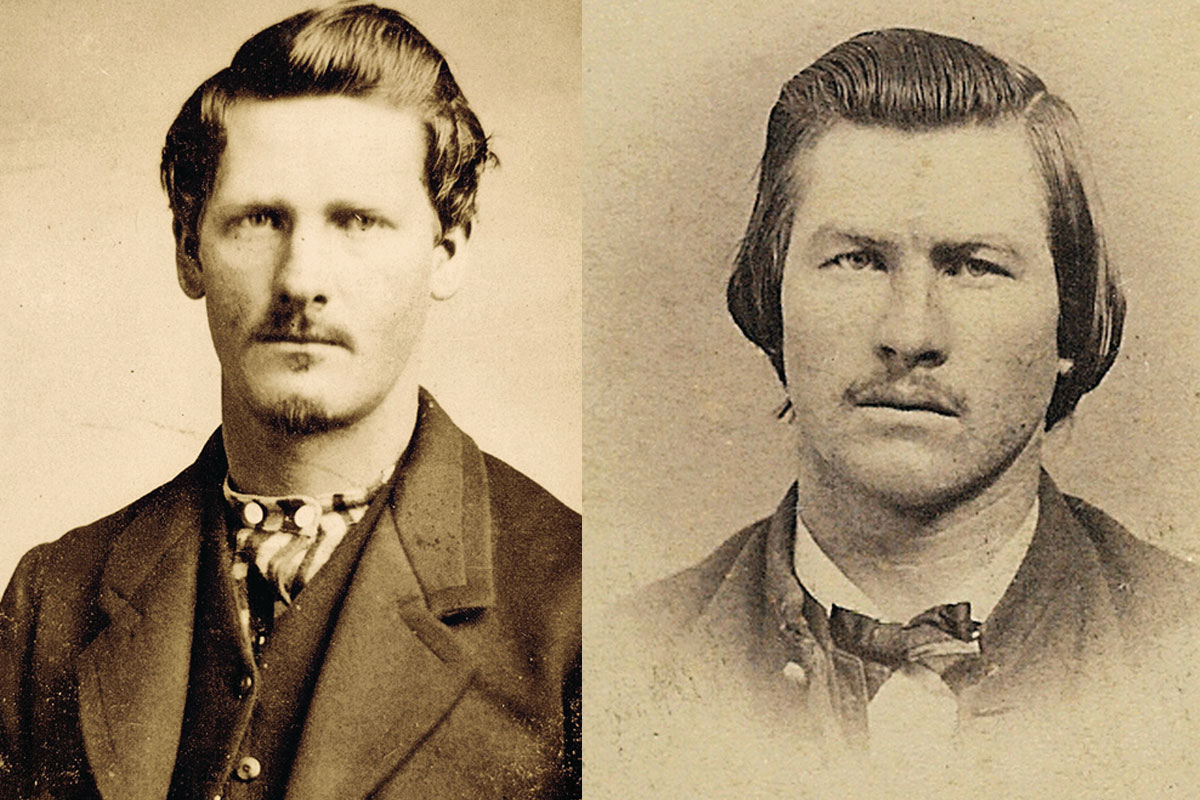

Events make clear that this was the Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp of O.K. Corral fame and enduring Western legend—a man in his mid-20s who was already acquiring a reputation, though of dubious prospect. And the gunboat incident of September 7, 1872, was not the first collision between him and the Peoria police that year.

On February 24, he and his brother Morgan had been seized in a raid on Jane Haspel’s brothel, in the city’s red-light district, close by the train yards, transient boardinghouses and hotels catering to commercial travelers. At a hearing shortly afterward, a prostitute nabbed with the Earps cinches their guilt, giving testimony to the effect that they had not been entrapped but had knowingly consorted with her, and each man paid a fine of $20 and costs. The raid was part of a campaign launched by the new mayor and his superintendent of police—Samuel Gill—to placate the “moral element” among their constituents by putting well-publicized pressure on the flesh trade. On this occasion, the amount of the fine suggests the Earps were convicted of being nothing more

than “johns.”

Two months afterward, on April 24, the prostitute who had turned state’s evidence against the Earps—Minnie Randall—committed suicide by swallowing six grains of morphine. The Peoria Daily Transcript noted that she had been an inmate of the McClellan building on Main Street, a house of ill fame within several blocks of Jane Haspel’s. It further remarked that the deceased had been stopping at McClellan’s with the notorious prostitute Sally Haspel.

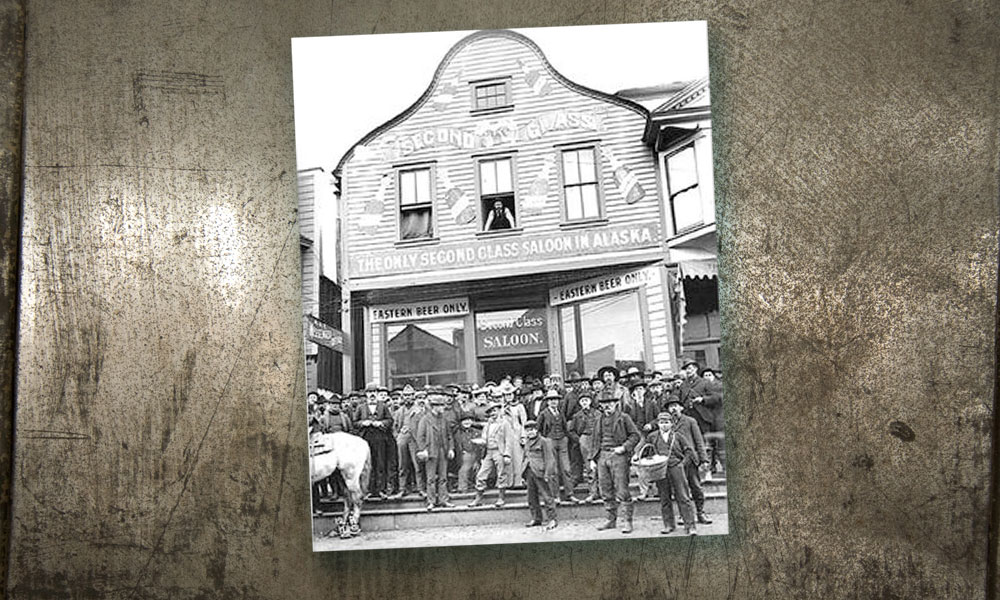

— True West Archives —

Less than three weeks later, Wyatt and Morgan Earp were again jailed by Captain Gill’s police force, as reported in the May 11, 1872, edition of the Daily Transcript: “That hotbed of iniquity, the McClellan Institute on Main Street near Water was pulled on Thursday night [May 9], and as usual quite a number of inmates transient and otherwise were found therein. Wyat [sic] Earp and his brother Morgan Earp were each fined $44.55 and as they had not the money and would not work, they languish in the cold and silent calaboose.”

The madam of the McClellan Institute was Jennie Green, whose previous residence had been a hovel situated in an alley near the corner of Washington and Hamilton streets, within spitting distance of Jane Haspel’s back door. The amount of the fines levied against Wyatt and Morgan suggests that the arresting officers considered them to be pimps and charged them as such.

The brothers cannot have relished the time spent in the city jail, however refractory they chose to be about working off their fines.

It may be that after serving their sentences, Wyatt and Morgan left Peoria—Wyatt temporarily and Morgan for good. In a memoir, their sister Adelia recounts how on her 11th birthday, June 16, 1872, they visited her at the family farm in Missouri and gave her “a whole package of pretty clothes.” By Adelia’s account, Wyatt and Morgan had returned from buffalo hunting with “quite a heap of money.”

The generally accurate recollections given by Earp when he had nothing to hide lead one to believe he concocted a plausible tale to account for the time he lingered in Peoria. Still, he and Morgan may have returned to his father’s farm in June 1872 and made a memorable appearance at their young sister’s birthday party. How they could have flashed “quite a heap of money” when neither could stump up enough to pay a $44.55 fine a month earlier is another matter.

If Wyatt did return to his family, the visit was a brief one, for probably no later than August he was back in Peoria or Beardstown or points in between. Somewhere he had to have teamed up with John T. Walton, owner of the floating brothel.

What Played in Peoria

Seeking to profit from human weakness and need, Wyatt and Morgan Earp found themselves caught in a double bind. First of all, they were outsiders, and, as such, parasitic, if not pestilential, in the eyes of the community. In 1872, “bummer” meant more to a Peorian than a mere good-for-nothing; it carried connotations of vagrant, vagabond, confidence trickster and applied specifically to the tide of unwanted immigrants that rushed down the Illinois River following the great Chicago fire of 1871.

Identified with these invaders, the Earps paid a price. Substantial fines appear to have driven them out of town by early summer, and when Wyatt returned on the gunboat in September (floating downriver like Detritus from the scorched Sodom to the north), he came in for another mulcting from the authorities and a tongue-lashing from the press that bid him be gone and carry on his business at “Hell’s gate.”

Editor’s Note: “Earps Gone Wild” is excerpted from “The Peoria Bummer: Wyatt Earp’s Lost Year” by the late Roger Jay in A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story be Told.