— Historic Image of Tombstone Courtesy True West Archives/ Image of Hugh O’Brian from “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp” Courtesy ABC/Design by Dan Harshberger —

The Wyatt Earp everyone knew has gone away. More than once. Perhaps no figure in American history has endured such an odd ride through fame. He has been portrayed as a magnificent hero and a lowly villain; a glory-seeking braggart and humble introvert avoiding the spotlight.

Writers have created and debunked mythical Wyatt Earps, time after time. It is only in the last couple of decades that we are growing to understand Earp himself and the many controversies of his life.

This is part of what makes Earp and his adventures so enduring—he is a mass of contradictions amid a stew of controversy. Since those gunshots went off in the street outside the O.K. Corral, the debate has raged whether he was a murderer or a brave lawman saving his town from outlaws.

In his own time, as early as 1888, newspaper articles around the nation portrayed Earp as both a hero and a villain, telling exaggerated tales or lapsing into total fantasy. The contradictory legacy would continue into the 20th century, when two major books swept the nation telling of a heroic Earp that rode against injustice. Walter Noble Burns, in his 1928 Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest, and Stuart Lake, in his 1931 Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, both created the Earp of legend: a valiant law officer saving the citizenry from an onslaught of outlaws. The books spawned a series of movies, and the movies built a legend.

Then came that TV series, telling American children the remarkable—and supposedly true—story of an unparalleled lawman who shot to wound, not to kill. The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp elevated him to a standard beyond reality. Even the lyrics to the theme song made him grand beyond belief: “The West it was lawless, but one man was flawless,” the ballad flowed from the TV screen into the ears of the children of America. There were those who adamantly believed this was pure bunk.

Earps of the Imagination

Burns, Lake, and the films were the glorifiers. They would be followed by the debunkers, the likes of Frank Waters and Ed Bartholomew, who portrayed Earp as the villainous head of a crime operation. The debunkers would be followed by the fabulists, a group of writers who fabricated stories for fun and profit. Glenn Boyer and Wayne Montgomery would be most notable among the throng.

Together, the three groups created Earps of the imagination. Readers could find any Wyatt Earp they desired, then passionately defend their beliefs by pointing to their sources.

A new era of Earp/Tombstone research began toward the end of the 20th century as researchers began seeking real sources rather than following legends. Jack Burrows’s 1986 John Ringo: The Gunfighter Who Never Was stripped apart the Ringo legend and began a series of articles and books based on evidence rather than yarns.

Before any real understanding of Earp and his situations could come about, the credibility of past writers had to be assessed. That became a serious project for Gary Roberts, Jeff Morey, Roger Peterson, Burrows, and myself during the work done on my book, Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend. By this time, Burns and Lake had fallen into disrepute by researchers who had torn past the veneer and realized that many of the tales were highly exaggerated and inaccurate. That had been the role of the debunkers.

As I worked on my book, it became increasingly clear that the writings of Glenn Boyer, then the reigning authority in Earp research, were highly problematic. Further developments proved that many of his assertions were entirely false.

Investigation continued when Jeff Wheat and S.J. Reidhead located documents from debunker Frank Waters that demonstrated that he, too, had fabricated much of the material that he put forward as fact in his 1960 book The Earp Brothers of Tombstone.

It became obvious that the writings long considered the most important in the understanding of Wyatt Earp were often supplemented with imagination—little more than fiction.

Legend and fabrication built Wyatt Earp into one of the most recognizable names in American history. Next came the challenge of finding the real Earp, the man beyond the legend and the truth about what occurred in those cowtowns and mining camps across the West.

Seeking the Truth

We were all starting anew. What was once believed as gospel truth about Wyatt Earp, his adventures, and those who surrounded him had been washed away, and we had to start over. A whole new beginning.

Most of the articles in A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story Be Told represent the new era of Earp research, the post-fabricator period where researchers have pored through original sources to present new and often shocking discov- eries. The most salacious, of course, is the previously unknown period when Wyatt and Morgan Earp worked in bordellos in Peoria, Illinois, followed by Wyatt’s stint on a floating brothel boat. All this came after Wyatt’s escape from an Arkansas jail.

The new research shows an Earp who is anything but flawless, rather an Earp who went through a lifetime of achievement, struggle and disappointments. He made many poor decisions in his life and a few very good ones. He was…human.

During much of the 19th and early 20th century there was a belief that boys needed positive role models. Biographies should glorify their heroic subjects so that emerging men would have great figures on which to model their lives. Burns and Lake created an Earp who served as that type of a positive role model. Some of what they wrote was accurate, but the real Wyatt Earp was far more complicated, far more prone to human desire and poor decision-making.

We are only beginning the reanalysis of Earp and his times, yet the Wyatt Earp who is emerging is neither the plaster saint of Lake nor the repulsive villain portrayed by Waters. He is a man—a man who faced difficult and complicated choices. Sometimes he got them right. Sometimes he got them wrong. Sometimes he believed the right people. Sometimes he was naively misled.

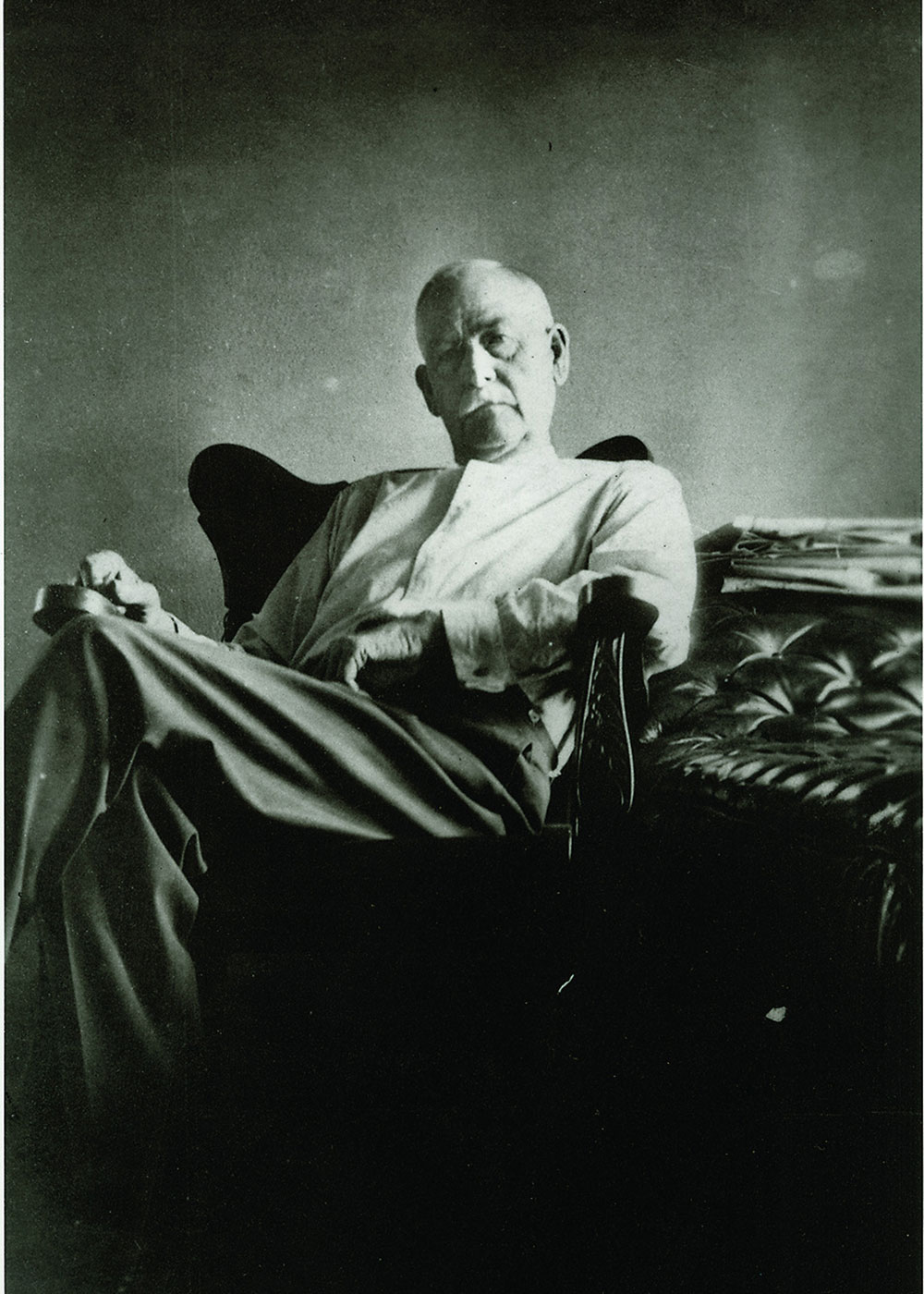

Some writers have portrayed Earp as a glory hound, actively seeking publicity wherever he could find it. Even this is replete with contradictions. There are numerous reports from those who knew Earp telling how he refused to discuss the old days and always avoided talking about the killing and mayhem. Friends and family members alike portrayed a very modest man who avoided the spotlight. In 1925, he wrote to old acquaintance John Hays Hammond, “Notoriety has been the bane of my life. I detest it, and I never have put forth any effort to check the tales that have been published in recent years of the exploits in which my brothers and I are supposed to have been the principal participants. None of them are correct….”

Yet, near the end of his life, the man who had so tried to elude publicity, decided to try and have his story told, with the aid of silent-picture superstar William S. Hart. Hart suggested a biography be written to precede the flicker, and Earp agreed. During this period, two writers—Fredrick Bechdolt and Frank Lockwood—met with Earp and would later recount how Earp talked at length about killings, the very subjects he had avoided for so many years. Bechdolt and Lockwood even said that Earp claimed to have killed outlaw leader John Ringo on the way out of Arizona, which is impossible, since Ringo’s death came four months after Earp left Arizona. Earp did not make the claim of killing Ringo to Lake.

In Search of the Real Wyatt Earp

So who was Earp? A glory hound or the same man who had shied from publicity for so many long years, trying to avoid undue attention? Or, does it make him a very human character who clumsily tried to adjust to different situations? A simple man of great complexity.

I believe all this makes for a far more interesting Wyatt Earp. He made many mistakes, but when the time to stand tall came to him, he showed enormous bravery. He is defined by his courage rather than wisdom or judgment.

I further believe that children are better served by understanding that heroes have human failings, too. Only by understanding the humanity—flaws and strengths alike—do we make future generations recognize they can strive for greatness, even with their own deficiencies.

Much of what the previous eras of writers claimed must simply be eradicated from the mind. One of Boyer’s more unusual assertions was that Lake had dug up a little-known, mostly forgotten lawman and turned him into a national figure. This is simply not true.

Even in his own time, Earp built quite a reputation. In 1889, he came North from his home in San Diego for a visit to the races in Sonoma County, north of San Francisco. On August 24, the Santa Rosa Democrat wrote, “Wyatt Earp is little given to talking about himself. And yet he has a reputation as wide as the continent—a fame made by deeds rather than words.”

This level of fame came after his time as a Kansas lawman and the gunfight in Tombstone, after which he led the Vendetta that captured national attention. He would draw far more attention for his ill-fated decision to referee the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons fight in 1896, when he awarded the victory to underdog Tom Sharkey on a foul, leaving Bob Fitzsimmons and a thousand of dissenters to charge that he had been bought off and fixed the fight. Newspapers across the nation mocked Earp, and the fight would be recalled for decades, with various writers rehashing the claims against him.

— Photo Courtesy Jeff Morey —

By the 1920s, a nostalgia period set in, with numerous recollections appearing in newspapers across the country telling of the still-in-living-memory Old West. Many of these articles centered on Tombstone—a saga that is the epitome of the West of Imagination. And, many of them were flat-out false, yet they served to elevate Earp’s recognition around the nation. In 1923, William S. Hart used Earp as a character in his movie, Wild Bill Hickok. Bert Lindley played Earp, and newspaper stories appeared around the nation telling of the film. Burns’s book followed in 1927 and sold well nationally.

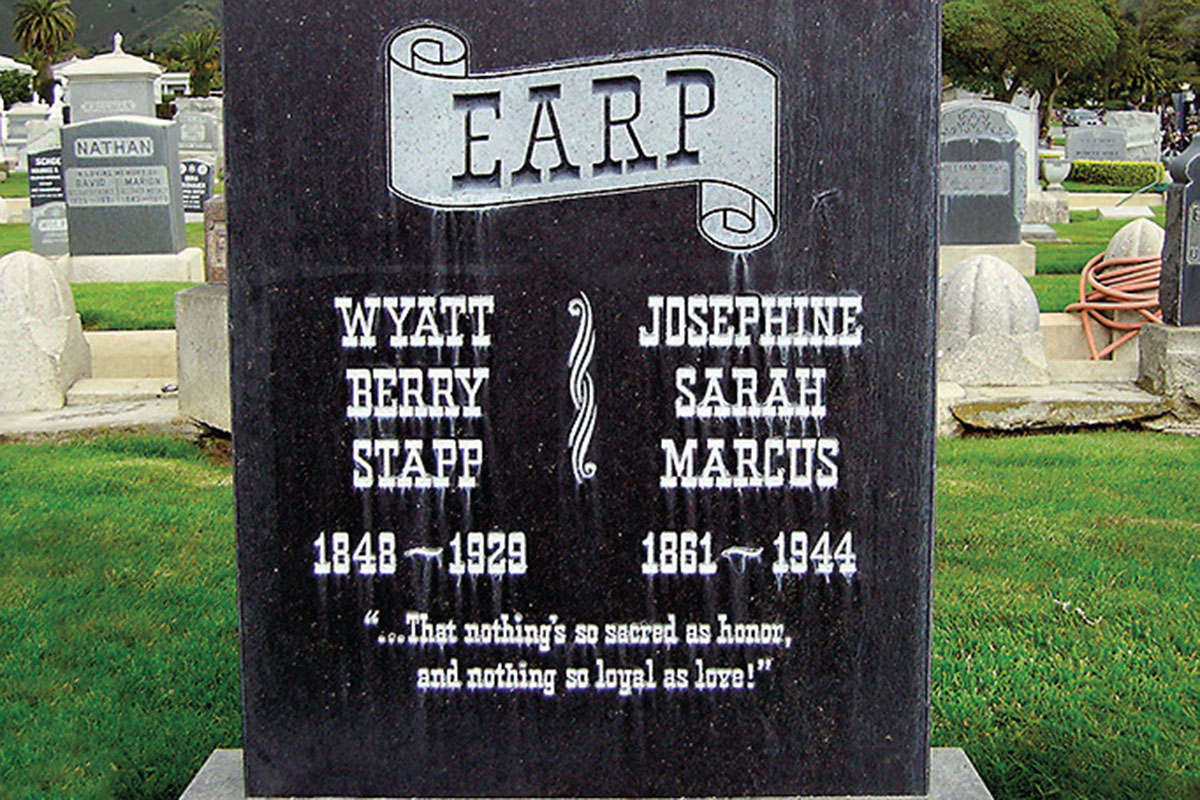

When Earp died in 1929, his obituary appeared in the New York Times and most other papers around the United States. Earp was anything but forgotten when Lake’s biography appeared.

— Grave Photo Courtesy True West Archives —

With the advent of online newspaper resources, we are finding new information with regularity and continually learning as more and more papers become available. One of the most interesting discoveries is ongoing. Kansas researcher Roger Myers found several articles concerning the long-disputed confrontation between Earp and Clay Allison in the streets of Dodge City. After Myers published his findings in Wild West, researchers Bob Cash and Chris Penn continued scouring old newspapers and located stories that further support the authenticity of such a confrontation. What happened is not like the absurd represen- tation by Lake of Earp facing Allison down in the middle of the street, but rather a canny outwitting, where Bat Masterson held a gun in the distance as Earp convinces Allison that any action would be fatal for him.

We are constantly learning more, as creative researchers discover new sources of information. When I first began researching, Gary Roberts told me that the general belief around the field was that everything that could be found about Earp had already been discovered. The only significant unknown material lay in the files of Boyer or longtime Earp researcher John Gilchriese, who claimed to possess an enormous number of documents he would be using in his Earp biography, a book that has never been published. Both Gilchriese and Boyer served as bottlenecks on Earp research, with aspiring historians assuming they could not penetrate the field. If they did, they would be met with humiliation when one of the giants revealed a secret that disproved their work. Boyer’s mysterious collection, of course, turned out to be mythological.

Epilogue

Gilchriese’s collection went to auction and did not contain the many treasures he claimed.

We have reached a new level in Earp research. So many are doing such good work, and A Wyatt Earp Anthology is a tribute to the many dedicated historians who are trying to find the truth of this mysterious legend and the many controversies that surrounded him. The work is far from finished, and future generations of researchers will keep hunting as we develop a better understanding.

Many Wyatt Earps have come and gone since the real man’s ashes were interred in a small cemetery south of San Francisco. Only now are we starting to understand the actual Wyatt Earp and the many ordeals he confronted.