–DF Barry/Courtesy Brian Lebel Auctions-Cottle Collection –

Scout’s Rest Ranch, known today as Buffalo Bill State Historical Park in North Platte, Nebraska, might seem like an odd place to start a road trip about Lakota leader Red Cloud. But think back…

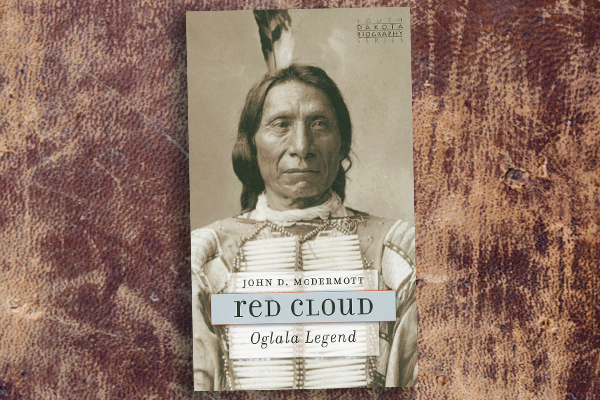

One of the iconic photographs of Buffalo Bill Cody has him posing with Red Cloud, “a warrior without peer,” Robert W. Larson writes in his 1997 biography, “who could not only command the respect of his own people but of his enemies as well.”

Granted, that photo was taken more than 1,500 miles east of here, at Madison Square Garden in New York City. In 1897, Red Cloud had traveled to Washington, D.C., to speak on behalf of his people. Afterward, he went to New York to catch Cody’s Wild West show. A number of Lakotas performed with Cody, and some of Cody’s cowboys were in the Lakota family. William “Bronco Bill” Irving had married a Lakota woman and spoke fluent Lakota. William “Billy” Bullock’s father had married a Lakota woman and was a key ally of Red Cloud. Irving and the younger Bullock—and cowboy-interpreter-and-sometimes-Deadwood-stagecoach-driver John Y. Nelson, one of Red Cloud’s sons-in-law, would serve as Cody-Lakota liaisons when the Lakotas began traveling with Cody’s show in 1883. Nelson had even served as translator, back when Cody was treading the boards in 1877, when Sword and Two Bears traveled with the theatrical troupe.

Besides, Cody and Red Cloud were a lot alike. Controversial figures. Warriors. Enemies. Maybe even allies and champions of the West. And while Scout’s Rest Ranch— and the home, built in 1886—is a beautiful place to visit, North Platte offers something else.

The Nebraska Years

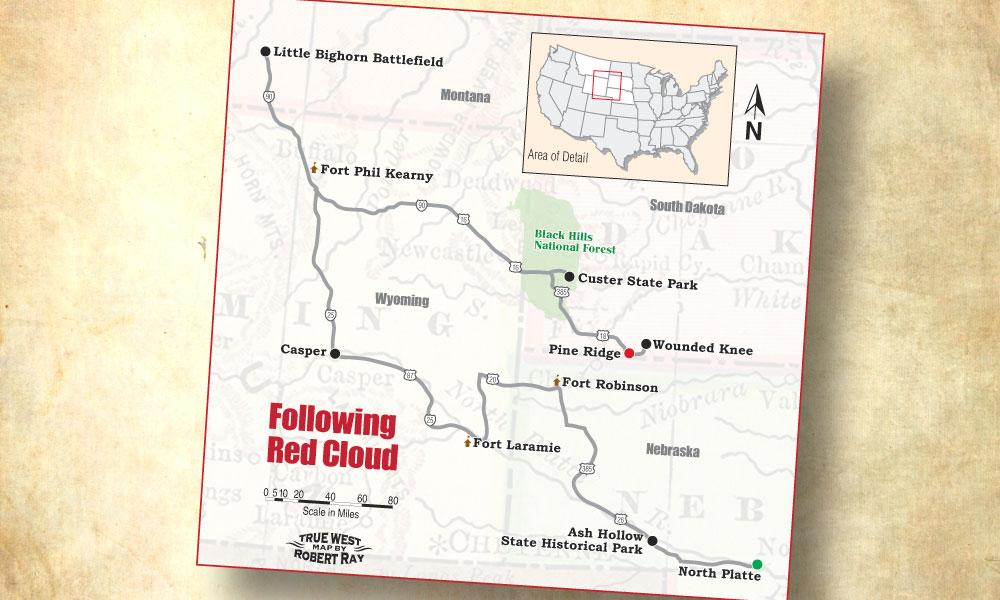

It’s not that far from Garden County, where Red Cloud was born in May 1821 on Blue Water Creek, near where General William S. Harney’s troops would fight the Lakotas at Ash Hollow in 1855 in what is now called “The First Sioux War.” The battlefield is on private property, but nearby Ash Hollow State Historical Park was used by Indians in prehistoric times long before white travelers often stopped there along the Overland Trail.

So that’s about as close as we can get to Red Cloud’s birthplace.

Red Cloud’s father, Lone Man, discovered whiskey from white traders and, an alcoholic, died in 1825. Red Cloud would speak out against alcohol all his life and insisted that he never drank himself. While he would come of age and become a legend in Wyoming, he spent many years—some of them controversial—in Nebraska, so we need to stop at Fort Robinson State Park, a sprawling, picturesque park that includes Army buildings (where you can spend the night), buffalo (which you can also eat) and the Red Cloud Agency.

After Red Cloud and others signed the Treaty of 1868 at Fort Laramie, the Red Cloud Agency was established in 1871, first near Henry, Nebraska, and in 1873 near Crawford. In 1874, the Army began construction on what would become Fort Robinson. Red Cloud didn’t care much for the fort. He liked things even less when Crazy Horse came there in 1877.

In April 1877, Red Cloud left the reservation with 80 Lakotas to persuade Crazy Horse to surrender, but once the dynamic Lakota leader had joined the agency, Red Cloud, Spotted Tail and other Lakotas grew jealous. That September, according to one accepted account, Red Cloud met with Gen. George Crook and others. Everyone agreed that Crazy Horse should be killed. The plot didn’t pan out, but two days later Crazy Horse was bayoneted in the back by a soldier and died. With Crazy Horse out of the picture, Red Cloud was back on top. Three weeks later, he joined an Indian delegation to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes in Washington.

All told, Red Cloud would make it to D.C. more than 20 times. The man got around.

Red Cloud in Wyoming

He especially got around in Wyoming, where he was less controversial, and mostly victorious.

Although he reluctantly signed the Fort Laramie Treaty in the fall of 1868, Red Cloud did not arrive at the post until the following spring. It was quite a show.

The post commander awoke to find Red Cloud and hundreds of warriors on the parade grounds, their families watching from a distance. The Army quickly tried to match the Lakotas’ show of force. Hours passed before the commander sent a message to the Indians, inquiring what they wanted.

Red Cloud’s answer: “We want to eat.”

The “grand old post,” Fort Laramie, now a National Historic Site, remains one of the best-preserved Army posts in the West. Originally a trading post established in 1834, the Army would not arrive until 1849, and the post would remain active until 1890.

Red Cloud made his name for himself at another Army post, so I’m off to Casper.

Platte Bridge Station had been established across the North Platte in 1862. After the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado in 1864, Indian attacks increased along the westward trails. On July 26, 1865, Cheyennes, led by Roman Nose, and Oglalas, led by Red Cloud, attacked an Army detail sent to escort a supply train into the post. Twenty-six soldiers were killed, perhaps another 10 wounded. One of the dead was Lt. Caspar Collins, so when the post was expanded, it was renamed Fort Casper. Only the soldiers couldn’t spell. In 1936, a Works Progress Administration project reconstructed the fort, and the Fort Caspar Museum still re-creates regional history.

Fetterman’s Fiasco

Of course, what really gave Red Cloud his name came the following year at Fort Phil Kearny.

The Montana gold strikes sent white settlers through Lakota country, and with negotiations between whites and Indians ongoing, Col. Henry B. Carrington was ordered to establish forts in the Powder River country. Fort Reno was established near Sussex, Fort Phil Kearny near Buffalo and Fort C.F. Smith in Montana.

Capt. William J. Fetterman arrived at Kearny in November and, according to legend, boasted that with 80 men, he could ride through the Sioux Nation. On December 21, sent to relieve a wood-cutting detail under attack, Fetterman got his chance. Leading his 80 men, Fetterman chased a decoy force of 10 Indians over a hill. Some 1,500 Indians waited for them on the other side.

The fight was over in minutes. No Army soldiers survived. And while Minneconjous Lakotas might have taken the initiative, Red Cloud got the glory. Hey, even in the 1860s, folks were calling this Red Cloud’s War. Though the whites prevailed in Hayfield and Wagon Box Fights, a peace was sought. In effect, Red Cloud won. The three forts were abandoned, and then burned by Indians.

The Post-Big Horn Years

Red Cloud remained at peace, relatively speaking, with the white men for the rest of his life. He wasn’t at the Little Big Horn, though his son fought there, but he would be there in a 1902 re-enactment, “totally blind and very feeble,” a newspaper reported.

The agency moved to the upper Missouri River in 1877 and to the renamed Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota a year later.

South Dakota is the heart of Lakota country today. The land that includes Black Hills National Forest, Custer State Park, the Mount Rushmore National Memorial and the Crazy Horse Memorial remains claimed by the Lakota.

So does Wounded Knee.

Red Cloud lost more prestige during the ghost dance troubles of 1890. Brulés kidnapped him for not supporting the dances. He said he was shot at by soldiers, and by Indians, and had to walk 16 miles to reach the Army lines.

After the Wounded Knee massacre, Red Cloud pretty much retired to his home in Pine Ridge, though he would make one last trip to Washington in 1897.

He died on December 10, 1909, and, having converted to Catholicism, was buried at the Holy Rosary Mission cemetery on Pine Ridge. Sixty years later, the mission was renamed Red Cloud Indian School, where the Heritage Center and an annual Indian art show remain highlights in a community ravaged today by poverty, unemployment and alcoholism.

Red Cloud’s legacy? Maybe he said it best during one of his visits to Washington in 1889. “When I fought the whites I fought with all my might. When I signed a treaty of peace I meant to do right, and I have often risked my life to keep the covenant.”

Red Cloud Agency was established here in 1873 for Chief Red Cloud and his Oglala band, as well as for other northern plains Indians, totaling nearly 13,000. During the Indian war of 1876, the agency served as the center for non-hostiles. After the treaty ceding the Black Hills to the U.S. was signed here in 1876, and the death of Crazy Horse in 1877, the agency was relocated to the Pine Ridge Agency, Dakota Territory.

The marker reads (sic):

ON THIS SPOT, CRAZY HORSE, OGALLALA CHIEF WAS KILLED SEPT. 5, 1877.

– Johnny D. Boggs –

– Johnny D. Boggs –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– W.R. Cross/Courtesy Library of Congress –

Johnny D. Boggs often wears a Lakota bolo, a gift from Lakota historian Joseph M. Marshall III. “If you want to understand the Lakota people,” Boggs says, “read anything and everything by Joe Marshall.”