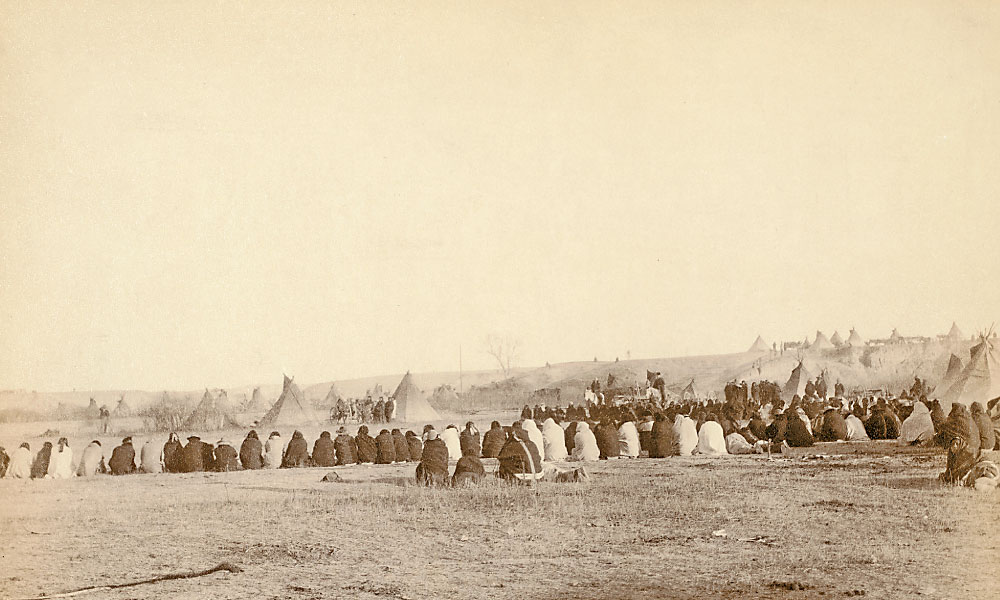

– All Photographs Courtesy Library of Congress –

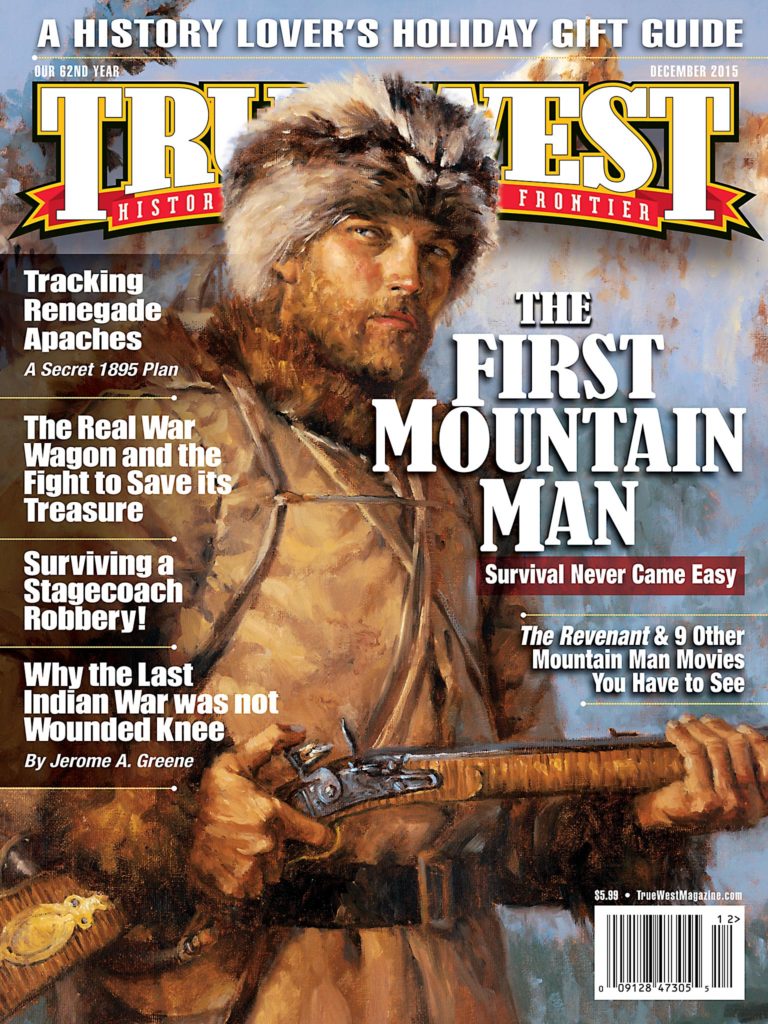

Coming at the conclusion of what white Americans call the frontier period in their history, Wounded Knee climaxed an era of intermittent warfare. Troops and Indians clashed throughout the Trans-Mississippi West in a 30-year on-again, off-again conflict that witnessed the government’s decisive subjugation of the Indians.

The December 28, 1890, encounter between U.S. Army and Lakota Sioux came in the wake of several other massacres of native peoples during that period—all of them undeniably premeditated—as punitive forces operating under the auspices of the United States forcibly subjected the Indians to the national will.

Wounded Knee followed Bear River in Washington Territory (present-day Idaho), where some 250 members of a village of northwestern Shoshoni Indians died facing attacking troops in January 1863. It followed Sand Creek in Colorado Territory, where at least 150 Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos fell before guns of a federalized cavalry onslaught in November 1864. And it came after yet another Army strike killed 250 Piegan men, women and children at the Marias River in northwestern Montana Territory in January 1870.

The circumstances leading to Wounded Knee two decades later differed markedly from these earlier engagements. These conflicts involved Indians resisting being placed on reservations. But Wounded Knee involved the Lakotas’ efforts to deal with critical survival issues facing them on their reservations.

As people came to understand later, the nonviolent Ghost Dance was only a side issue. As Valentine McGillycuddy explained, “Had these people been well fed the ghost dance would never have been heard of. The dance and its ceremonies was like the voice of a feast to a starving man…. They cried for help from above, all other help having failed.”

Wounded Knee, therefore, was not the last of the Indian Wars, as it is frequently called. That distinction rightly belongs to the Apache outbreak preceding Geronimo’s surrender in 1886. Wounded Knee was different.

Non-Indian society commonly called Wounded Knee a “battle.” In fact, the only real battle to occur was in each Lakota’s struggle to escape the onslaught and live.

The human loss was incalculable, as was the physical and emotional devastation. Entire families, tiospayes, and tribal societies were disrupted, notably at Cheyenne River and Standing Rock, but also at Pine Ridge, Rosebud and elsewhere. Virtually no one in the small reservation communities escaped the impact.

Certainly the Sioux Land Commission and its aftermath, including the rise of the Ghost Dance among the Lakotas, served as a catalyst for what happened. But strategic failure occurred at Pine Ridge Agency in misidentifying a need for troops, resulting in the overreaction that brought them onto the reservations only to aggravate conditions.

Questions about the massacre itself loom even larger. No premeditated intent seems to have existed. Indeed plans were in place: the trains were being readied to move Big Foot’s people to Omaha, Nebraska. The explosive intensity of the violence must in part rest with the inordinate number of untrained troops arrayed in opposition to the Sioux and with Col. James W. Forsyth’s failure to manage his 7th Cavalry command suitably. But the events that followed the initial exchange in the council area remain not only numbingly horrifying, but largely inexplicable.

In the hurriedly escalating fog-of-war scenario, the critical tactical failure lay in permitting the Indians to break through the soldier cordon formed by Troops B and K. That collapse of control escalated the conflict at flash speed by redirecting the reacting soldiers’ gunfire into the noncombatants beyond and tilting the ensuing action into a scene of uncontrollable riot.

The increasing density of the gun smoke coupled with the excessively lengthy shooting inside and particularly outside the council area aggravated the breakdown. As a result, many more Sioux, especially women and children, were slated to die in and along the big ravine and among subordinate gullies and hillocks as they sought to flee the unfolding slaughter.

Forsyth’s actions in distributing his troops preceding the outbreak probably caused inadvertent deaths and injuries to at least some of his own men. That question might only be answered by exhumation and forensic analysis of their remains.

We know the manner in which Wounded Knee occurred. The larger question of why it happened at all will probably remain unresolved. It likely could have been avoided with improved communication and greater tolerance and patience all around, unfamiliar concepts at the time when the government sought to impress its control over tribal populations.

Historian Walter Camp said it well: “While it was the Indians who were doing the dancing it was really the whites who saw the ghosts.”

This is an edited excerpt from Jerome A. Greene’s Spur-winning American Carnage: Wounded Knee, 1890, published by the University of Oklahoma Press.