— Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France —

The man sprawled in a Portland doorway still clutched what had killed him: a bottle of laudanum. Overdosing the previous year, he’d fallen from a hotel balcony and lingered on death’s threshold. No mere drug addict or bum, the 43-year-old son of Scottish and German immigrants had returned to Oregon, where he’d lived in his teens, to lecture about his exploits as an Arctic adventurer—if one of the less famous ones. Laudanum eased his recurring stomach pains, caused perhaps by “an excess of conviviality.”

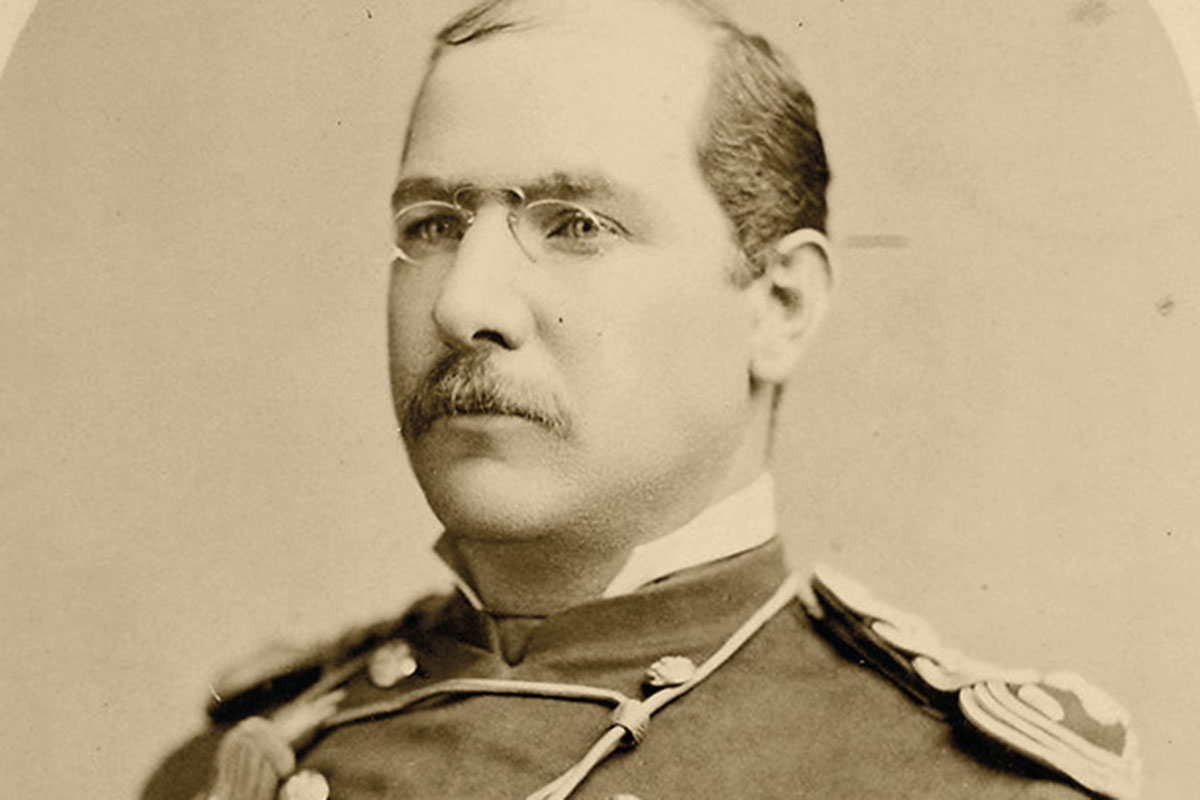

The route north had been circuitous. A former West Point graduate, the corpulent, spectacled and balding Frederick Schwatka sported a mustachio, studied law and medicine and served with the 3rd Cavalry. He led the initial charge at Slim Buttes on the Great Sioux Reservation, a dash Charles Schreyvogel rousingly painted. Avenging Custer after the grueling “Horsemeat March” of 1876, Gen. George Crook destroyed American Horse’s village before repelling a Crazy Horse counterattack. On the first day of fighting, Lieutenant Schwatka, head-ing 25 troopers, galloped through the dust that crazed Oglala ponies were kicking up, firing his pistols at tipis.

— The 1889 woodcut from “Rundschau für Geographie und Statistik” COURTESY OF TRIPOTA/ Photo COURTESY OF BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE

DE FRANCE —

In 1878 he volunteered his pluck for an American Geographical Society search for relics of Sir John Franklin’s Northwest Passage expedition, missing since 1845. During this 11-month, 3,251-mile dogsled journey in –60-degree weather, Schwatka hunted muskoxen and—when in Rome…—ate like the Inuit and slept in “peculiarly constructed domes of snow.” He located naval artifacts, wreckage from one of Franklin’s longboats, and skeletal remains of four bodies scattered about.

Active, with a keen mind, Schwatka acquired Native language vocabularies while dabbling in botany and zoology. He built and launched rafts after crossing the Chilkoot Pass for a U.S. Army reconnaissance 13 years before the Klondike strike brought gold-hungry crowds. His party floated the Yukon River source to sea. At 1,300 miles, it was the longest journey by logs at the time, “the most difficult part

of which was unknown.” They dodged “bowlders,” sweepers (buoyant toppled trees), and “water like small geysers” that “made matters very uninviting for navigation in any sort of craft.”

— Courtesy of HathiTrust —

In 1886, his reputation won Schwatka the leadership of a New York Times expedition to North America’s second-highest peak, Mount St. Elias. The precipitous climb astride the new territory’s contested Yukon-Alaska border began in Icy Bay. After less than two weeks of facing fast, silt-swollen creeks and Tyndall Glacier’s crevasses, Schwatka—in poor physical shape—sickened and aborted the first documented summit attempt.

He lies buried in Salem, Oregon. His grave—marked unlike those of most Franklin men—lacks the lecturer’s eloquence. Died Nov. 2, 1892, the plain headstone reads. And, summing up a short lifetime’s passions: Explorer.

As a longtime rafting guide and Alaska resident, Michael Engelhard admires Schwatka’s long-distance feat. Trained as an anthropologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, he loves this explorer’s attention to ethnographic detail.