— True West Archives —

In 1830 lawyer George Catlin packed a case with pencils and paper, paint and brushes, and went to St. Louis where he met with William Clark, then the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Catlin wished to travel the route taken earlier by the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery. His intention was to see and make an artist’s view of the American Indians living along the Missouri River.

When Clark set out on a diplomatic mission to meet with tribal leaders in a council at Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin, Catlin accompanied him. This journey exposed Catlin to the landscape and the tribes along Mississippi River and launched his efforts to paint the chiefs and other Indian leaders. From 1830 until 1837, he explored the West, traveling and painting members from 48 tribes as well as 175 landscapes. He painted 300 portraits of prominent Indian chiefs and tribal members, and he collected Indian clothing and artifacts, including a Plains Indian tipi.

Gateway to the West

— True West Archives —

St. Louis served as Catlin’s base of operations, which is where we begin following a portion of his trail through the West. Gain an understanding of westward expansion at the recently renovated Jefferson Memorial and St. Louis Arch. This place has rightly been identified as the Gateway to the West. Like Catlin, many other explorers and adventurers started their journeys here. When Catlin was in the city, it served as a primary business district for fur traders and the trappers who supplied them with pelts.

In 1832, already familiar with much territory along the Missouri River, Catlin again followed the river, this time heading upstream to Fort Union. On the route he

met with, and later created portraits of members of the 18 tribes he visited, including the Pawnee, Omaha, Ponca, Hidatsa, Cheyenne, Mandan, Assiniboine, Crow and Blackfeet.

From St. Louis head west and follow the Missouri River across northern Missouri to Kansas City. Allow a good portion of a day to visit the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum, with its small but significant collection of American Indian art and artifacts, and a large and diverse collection of art. There you can enjoy an on-site restaurant, take part in docent-led tours or explore the museum on your own.

Across town, visit the Arabia Steamboat Museum and its collection of 1856-era trade goods ranging from leather shoes to fine china, perfume to buttons and sewing needles. These goods were part of the cargo on the Arabia when the ship went down after hitting a snag in the Missouri River. The river quickly covered the vessel and its 200 tons of cargo, but a group of local treasure hunters found and exhumed it in the 1980s, later restoring the goods and placing them in the museum.

North Along the Missouri

— Courtesy Missouri Tourism —

From Kansas City, continue north on I-29 to Omaha, Nebraska, with its equally impressive collection at the Joslyn Art Museum. A great interim stop at Nebraska City can include a visit to the Missouri River Basin Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center.

North of Omaha, visit the DeSoto Wildlife Refuge and see the goods of another Missouri River steamboat wreck—the Bertrand—which was also located in the Missouri River flood plain, until found and the cargo recovered and restored. Like the Arabia downstream, the Bertrand carried cargo for use in Montana and had a variety of trade goods, such as thousands of trade beads, which were highly prized by the Indians living along the Missouri.

In his painting Pipestone Quarry on the Coteau des Prairies (1836-1837), Catlin took artistic license with the landscape at the Pipestone quarries in Minnesota, which he described as “a perpendicular wall of close-grained, compact quartz, of twenty-five and thirty feet in elevation, running nearly North and South with its face to the West, exhibiting a front of nearly two miles in length.”

— True West Archives —

This ancient quarry has been mined by American Indians for generations. The soft red stone, which lies deep under a layer of dirt and Sioux Quartzite, has always been mined using hand tools. During the era Catlin was here, those tools included stone hammers and wedges. Today the pipestone quarries are part of Pipestone National Monument. Twenty-three federally recognized tribes in the U.S. and Canada oversee the use of the quarry. The men and women who come here to remove the soil and quartzite as they dig down to the pipestone layer, still use only hand tools, including small and large hammers and steel wedges. They haul the discarded rocks and dirt out using buckets and wheelbarrows.

Although American Indians refer to this special—and to them sacred—stone as pipestone, it is also called Catlinite for the artist George Catlin after his paintings drew attention to the landscape and the resource. He painted portraits of Indian leaders holding their pipes that had distinctive pipe bowls hand-carved from the red stone.

The Upper Missouri River Valley

Catlin painted members of the Mandan Villages, near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, visualizing members of that tribe at a time before their villages were decimated by smallpox epidemics. Visit locations important to the Mandans near Bismarck and then continue to the northwest to Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site. Lewis and Clark spent time here, and Catlin painted the location on his trip west.

The artist continued up river to the fur trade post at Fort Union, which dominated the Upper Missouri River during that early period of the American fur trade. Today Fort Union is a national historic site, carefully restored to interpret its early history, making it an excellent place to step back to the time of Catlin’s explorations.

Legacy of George Catlin

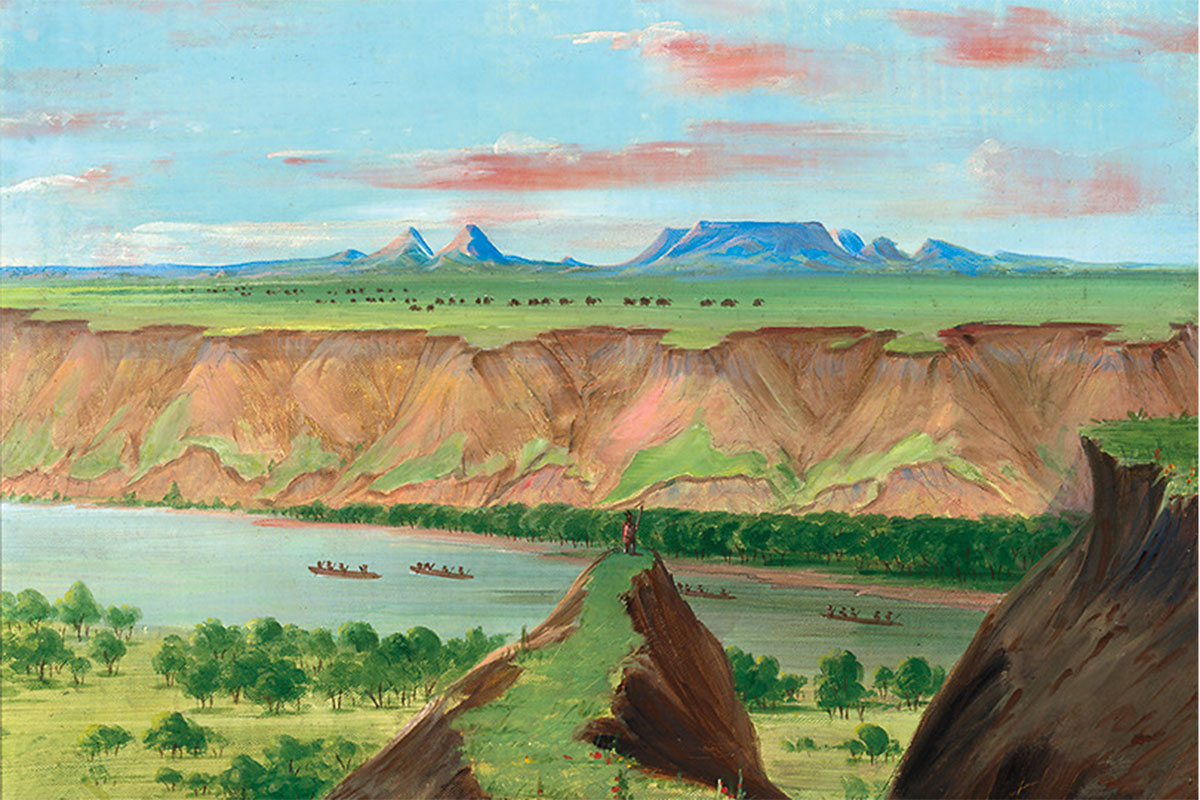

— Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, oil on canvas, 13 9/16” × 17 × 1 9/16” 1852, Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation, 1955 —

Catlin’s work gained wide attention in 1837 when he opened the first commercial exhibit of his paintings in New York City. People paid 50 cents to visit the exhibition and he later took the paintings to other Eastern cities. In 1839, Catlin sailed for Europe, taking his artwork on a tour that included Paris, Brussels and London. He gained accolades from King Louis-Phillipe of France and Queen Victoria in England, but found the cost of moving

the massive collection impossible to bear, so he returned to the United States where he undertook many ventures to make money.

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

The lawyer-turned-artist was far better at painting than making money, however, and he tried to sell his collection to the U.S. Government, in an attempt to recover enough to pay his debts, and to keep his life’s work together. He failed in that effort, and ended up in debtors’ prison in London for a short time until Joseph Harrison, an industrialist and railroad tycoon in the U.S., bought Catlin’s collection.

Harrison paid Catlin’s debts and the artist was released from prison. Catlin spent the next 18 years traveling through South America and Europe, recreating his Indian artwork, and painting new pieces as well. Catlin’s son and wife had died before his time in debtors’ prison, but his daughters survived him and they sold his later work to another collector.

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

Fortunately for all Americans, the nearly complete surviving set of Catlin’s first Indian Gallery, which was painted in the 1830s, is now part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection. The National Gallery of Art in New York City, New York, curates another 700 sketches.

Some of his most recognized images are Sioux Indians Hunting Buffalo (1835), Hunting Buffalo Camouflaged with Wolf Skins (1832) and Seminole Chief Osceola. While often romanticized, the paintings are an important representation of the American Indian tribes Catlin encountered on his journeys into the West.

Candy Moulton is working on three new films to be part of the new Pipestone National Monument visitor center exhibits, which will be installed this fall.