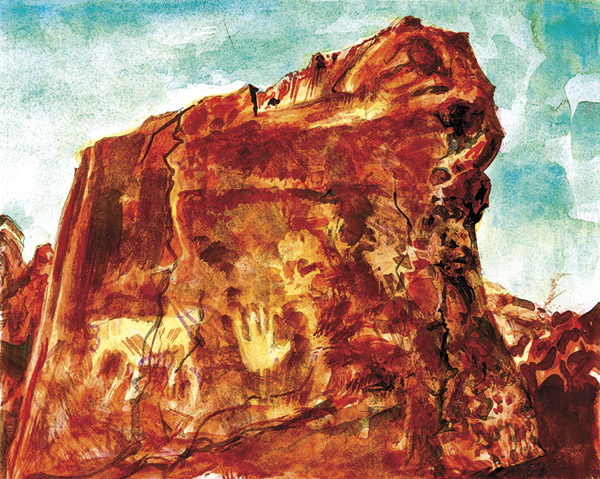

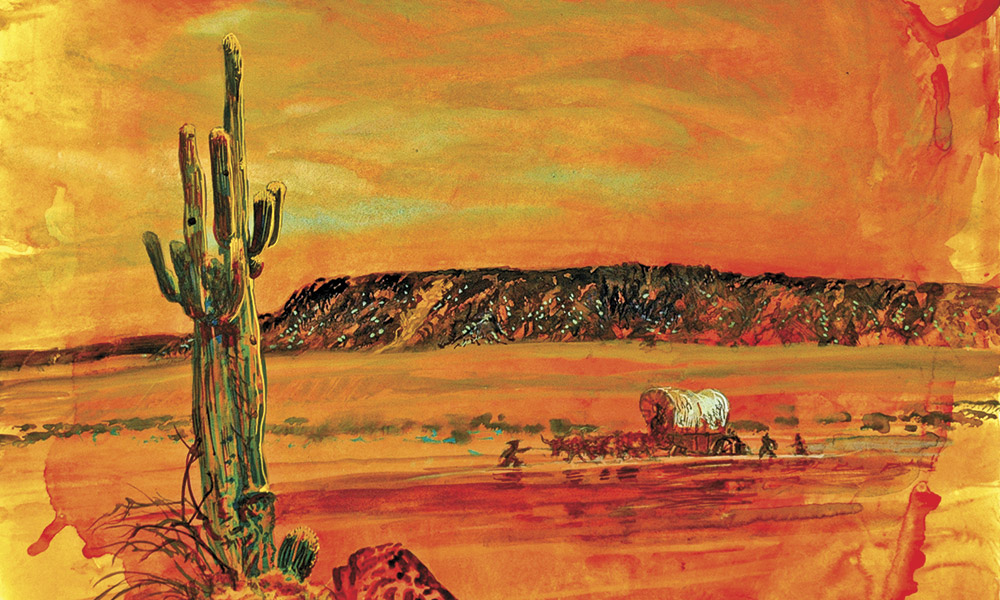

— All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell unless otherwise noted —

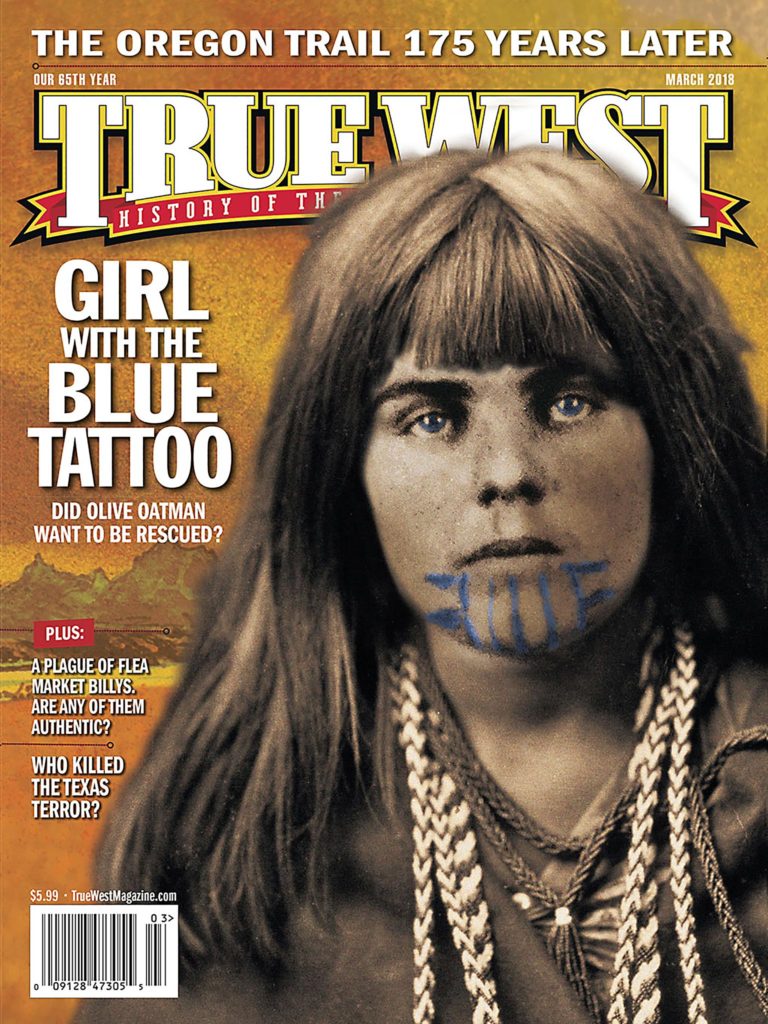

In 1857, Olive Oatman’s ghostwriter said this about her life story: “Much of that dreadful period is unwritten, and will remain forever unwritten.” Never say never. Here we are, 161 years since the Rev. Royal B. Stratton wrote those words, and we are ready to look at the brutal truth. Did Olive suffer a “fate worse than death” during her years of captivity among the American Indians? What follows is a closer look at the historical evidence.

— Mohave Indians, Illustrated by Balduin Möllhausen, during Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple’s 1853-54 expedition —

A Continuous Picnic Goes South

Like so many bad trips, this one started out as a fun adventure. The so-called Brewster wagon train left Independence, Missouri, on August 10, 1850. Ninety-three religious pioneers, seeking a life in the Land of Bashan, headed west in 43 wagons, loaded down with eight months worth of provisions.

“It was a continuous picnic and excitement was plentiful” is how Susan Thompson described the journey she took at the age of 17.

She described the food prepared: “The stores of jerked meat, dried apples and berries, flour, corn beef, meal, preserved fruits, bacon and beans that we had prepared during the spring months….”

The wagons stopped every two or three days, she added, “while the women baked and washed, the men hunted for antelopes or buffalos or smaller game…. Often, when we were camping near a stream, we had quantities of fresh fish.”

“…In the evenings we gathered about the campfires and played games or told stories, or danced…the young folks danced in the light of the campfire and lard-burning lanterns…. There was plenty of frolic and where there are young people gathered together, there is always plenty of love-making.”

Of course, the good times didn’t last. Petty infighting, alternative visions and illnesses took their toll. So much so that by the time the wagon train reached Socorro, New Mexico Territory, the ranks had been cut in half. Once those dwindling number of immigrants reached Maricopa Wells (south of present-day Phoenix, Arizona), the wagons had been reduced to three.

A month later, one wagon would push on toward the Colorado River, where the Edenesque Land of Bashan allegedly awaited, at the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers. That wagon was piloted by Roys (also styled as Royce) Oatman.

From Maricopa Wells, the Oatman family, took off alone. They traveled 1,800-some miles and were 120 miles from their goal.

West of the great Gila Bend, the Oatman wagon bogged down and had trouble crossing the river. Halfway across, the oxen gave out; all the coaxing and pulling didn’t work. As nightfall set in, the family was able to push the wagon up on a sandbar, to try and wait out the surging water, so they could continue the journey.

The water kept rising into the night and even snuffed out the family’s meager fire. The kids huddled together under their wagon and one heard their father say, “Mother, mother, in the name of God, I know that something dreadful is about to happen.”

If Roys actually said this (the comment was attributed to him after the events that followed), no truer words have ever been spoken.

Did Olive Oatman Want to Be Rescued?

Mary Ann was eight years old when she and her 13-year-old sister Olive were kidnapped by Western Yavapais west of present-day Gila Bend, Arizona. The raiding party killed her parents and four of her siblings, although a brother, Lorenzo, 14, survived. The sisters marched, barefooted, some 90 miles north to a village, where they were treated brutally, as slaves.

About a year later, a party of Mohaves came to the village and bought the girls, paying two horses, blankets and vegetables. They marched the sisters northwest to the Mohave Valley, which straddles the Colorado River, where they were taken into the home of one of the Mohave chiefs, on the site of the present-day Needles, California. What happened next is controversial.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Here’s the essence of the heated disagreement: Olive and her sister either spent their time with the Mohaves as houseguest-slaves (this is Olive’s version, after her release), or Olive was married to a chief’s son and had two of his children. Even more, a newspaper account claimed both Olive and Mary Ann married Mohave chiefs. If true, this makes the tale all the more sordid because Mary Ann couldn’t have been more than 12 years old.

One glaring omission in Olive’s version of her post-captivity story is that Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple’s railroad expedition came through the Mohave Valley in February 1854 and spent a week there meeting with the prominent chiefs and traversing the area where Olive claimed to have been held. If she wanted to be saved, why didn’t she make herself known?

Here is what Whipple recorded, on February 25, about the captives he saw: “It is said that several sad-looking fellows in the crowd are slaves, prisoners taken in the last expedition against the Cocopas. In the military code of this people, a captive is forever disgraced. Should he return to his tribe, his own mother would discard him as unworthy of notice. There are only two Cuchans, Jose and his friend; others are said to be on their way hither.”

From this we know that captured “slaves” among the Mohaves were beneath contempt, which is not an unusual cultural perspective for people at that time.

Whipple also recorded this, about the women he saw: “Young girls wear beads. When married their chins are tattooed with vertical blue lines, and they wear a necklace with a single sea-shell in front, curiously wrought.”

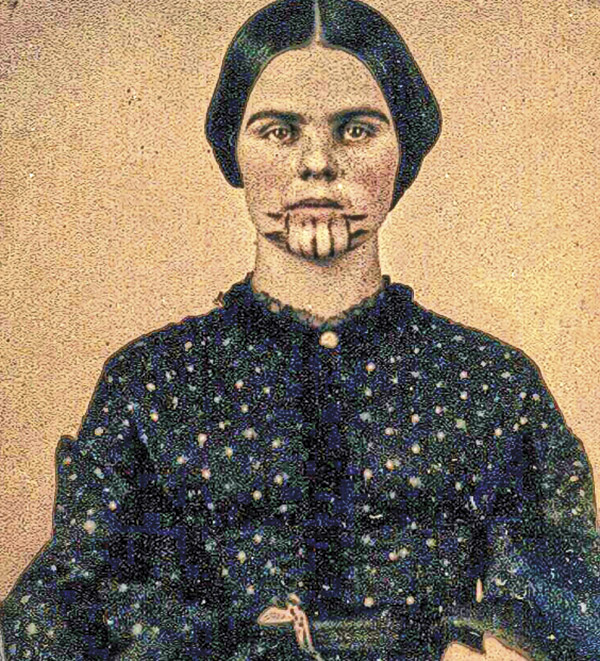

In 1856, a messenger from Fort Yuma found Olive, with blue vertical tattoos on her chin, among the Mohaves. Yet Whipple and his men never mentioned seeing Olive or her sister with the tribe.

Were the two girls hidden from the visitors? Or were they hiding themselves because they didn’t want to be found? The latter gains some credence when we take into consideration Olive’s later account of exactly when Mary Ann died of starvation. She kept moving the date, trying to avoid the obvious question: If Mary Ann was ill in February 1854, why didn’t Olive reach out to the U.S. expedition? The inevitable conclusion, at least to me, is Mary Ann had already died, and Olive had assimilated into the tribe, had children by a Mohave and didn’t want to be found.

Not every historian agrees that Olive had children while she was a captive.

Author Margot Mifflin says no: “Olive almost certainly didn’t marry a Mohave or bear his children. If she had, it would have been a highly unusual, thus memorable, piece of tribal history.”

Mifflin, whose 2009 book, The Blue Tattoo, was featured in the August 2009 issue of True West (“10 Myths About Olive Oatman”) goes on to say, “Although she married after her ransom, Olive never had biological children, which raises the possibility that she couldn’t. Finally, a half century after her ransom, when the anthropologist A.L. Kroeber interviewed a Mohave named Musk Melon who had known Olive well, he said nothing about her having been married.”

This is a solid argument on why Mifflin believes Olive did not have biological children, period. In fact, Olive, herself claimed nothing “improper” transpired between her and her captors, although that was after her ghostwriter, Royal B. Stratton, got ahold of the story and cleaned it up for his 1857 book, The Captivity of the Oatman Girls.

The most compelling argument for her having children comes from a friend of the Oatman girls, who was on the Brewster wagon train with them, before the massacre. Susan Thompson was living with her father and husband at the former’s inn in Monte (today El Monte), California, when Lorenzo and Olive, reunited in February 1856, stopped there on their way from Fort Yuma. Most important, she sees Olive before the famous captive meets Stratton.

Late in life, Thompson described the visit. She claimed her friend Olive was a “grieving, unsatisfied woman, who somehow, shook one’s belief in civilization.”

Susan also remembered that Olive confessed to being the mother of two Mohave children and that having to leave these children behind was the source of her grief.

Yet Mifflin dismisses Thompson’s claim: “Compelling as it is, the statement is unreliable: [Thompson] also claimed Olive lived with the [Thompson] family for four years (in fact it was for two months after her ransom).”

Brian McGinty, author of The Oatman Massacre, offers a different take. “I believe she may have [had children]. There were reports that she did, as detailed in my book,” he states. “Her unhappiness in later years may be explained by sorrow over the loss of her children. The eagerness with which she greeted Irataba in New York in 1864 may also be linked to that. However, there have been denials by Mohaves. Perhaps they wanted to avoid recriminations from whites.

“To the best of my knowledge, there has never been convincing proof that Olive did or convincing proof that she didn’t have Mohave children. The question is vital to understanding the tragic story of Olive Oatman and should not be dismissed out of hand, as at least one writer has. Some convincing proof may eventually emerge. I hope researchers will continue to pursue the question.”

Olive herself claimed she never had sexual relations with her captors. “She has not been made a wife, as has been heretofore erroneously reported, but has remained single, and her defenceless [sic] situation entirely respected during her residence among the Indians,” the Los Angeles Star reported in 1856, when covering Olive and Lorenzo’s arrival to Monte.

But even today, women do not feel comfortable discussing rape or sex forced during captivity. Perhaps this is what Stratton meant when he wrote, “Much of that dreadful period is unwritten, and will remain forever unwritten.”

“The unspoken underpinning for the entire Olive Oatman story is the question of her sexual relationship with her captors,” says Paul Andrew Hutton, University of New Mexico professor of history. “This was something the Victorian mind fed on. The Puritans before them had made this a central part of the captivity narratives that formed an important part of colonial American literature. The ‘fate worse than death’ may seem a quaint concept today, but it was very real in the 19th century. So real, in fact, that Gen. George Custer had standing orders that his wife Elizabeth was to be shot rather than allowed to fall into the hands of the Indians.

“Not only did Olive Oatman not die in captivity, she had grown into a young woman of striking beauty during her time with the Indians. The tattoo on her lovely face only fueled the Victorian mind—what else had the ‘savages’ done to her? That tawdry undercurrent of suspicion fueled the success of Stratton’s book and the lectures that kept Olive’s story before the public. That question, of course, despite the sea change in public morals, still fascinates us.”

The final word is perhaps best summed up by McGinty, who concludes his book with this haunting passage:

“Perhaps the story has no end—at least not in the conventional sense. Perhaps there is no date on a calendar or place on a map that represents the last chapter in the tragic history. Perhaps it will end only when the truth is known and sober minds can reflect on it. Perhaps it will really be over only when all the characters in the drama are released from the captivities—physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual—that so long and so forcefully held them in their grip.”

Olive Lost Two Mothers

One of the true and purest heroines in the Olive Oatman story is a Mohave woman named Aespaneo. She literally saved Olive’s life when she discreetly gave the 13-year-old captive her last food. “Had it not been for her,” Olive later said of the chief’s wife, “I might have perished.”

When Olive’s younger sister, Mary Ann, died of starvation, believed to be in the spring or summer of 1855, Aespaneo came to Olive’s side to weep over the body and share her grief, states Brian McGinty in The Oatman Massacre. And when the Mohaves began to prepare Mary Ann’s body, in Mohave fashion, for cremation, Olive’s Mohave mother, Aespaneo, interceded and allowed Mary Ann to be buried in the Christian custom. Aespaneo even insisted her husband provide two of their best blankets to wrap the girl for the burial.

After Olive left the Mohaves and returned to the white world, Aespaneo probably raised Olive’s children.

Eight years later, when Olive was living in upstate New York, she read about Irataba, the great Mohave chief, touring the East Coast (he may have even met President Abraham Lincoln). When Irataba reached New York City, Olive took the train to Manhattan and looked him up at the elegant Metropolitan Hotel. They met in the lobby. After clasping him with the left hand (held as a sacred pledge among the tribe), she asked about the Mohaves and her family. Irataba told her that Aespaneo’s daughter still hoped she would “tire of her pail [sic] faced friends & return.”

Although Olive was clearly touched, she never returned to the Mohaves.

Five Who Knew the Truth

After five years in captivity, when Olive Oatman was repatriated to Fort Yuma, she was so thoroughly assimilated into Mohave culture, the commander did not recognize her as a white woman. Someone had to pull back her hair and show the whiteness behind her ear to convince him.

• Olive’s brother Lorenzo miraculously survived at least four death blows to his head with a war club. After being rescued by two Pima tribesmen, Lorenzo made it to Fort Yuma, where he was successfully treated and rehabilitated. Moving on to California, Lorenzo tirelessly pleaded, with any authority who would listen, to try and find his sisters. When he rushed back to Fort Yuma five years later to meet his only surviving sister, they sat in a room together for an hour and said nothing. He did not recognize her and was stunned at her transformation.

• After her reunion with her brother, Olive traveled with Lorenzo by stage to Monte (today El Monte), California, and stayed with Susan Thompson, who had been on the Brewster wagon train with them. Years later, Thompson admitted Olive had confessed to being the mother of two Mohave children.

• A Methodist minister, the Rev. Royal B. Stratton met Olive in Yreka, California, and interviewed her at length for his book that became a national bestseller. In the book, he admitted he had purposely left out some episodes and facts. Since the book was first published by an arm of the Methodist Church, we can imagine that anything sexual would be a subject to leave out or gloss over.

• Sharlot Hall had the honor of being the first woman to hold an office in the Arizona Territorial government, and she is commemorated by a museum in Prescott, Arizona. Hall was among those historians who believed Olive became a mother, writing a letter to a researcher in 1906 declaring, “Olive had two children while among her captives, and one of them sometimes visits Fort Yuma.”

Heart Gone Wild Final Thoughts

Olive was caught between a punishing Christian culture and an exhilarating and hedonistic Mohave culture: suppression begets overflow. In modern terms, she went with the flow. She wasn’t alone. Other captive stories offered similar outcomes. Comanche captive and mother Cynthia Ann Parker comes to mind. In the 1970s, psychologists labeled the bond that can form between captives and their captors “Stockholm Syndrome.”

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

Olive did what she had to do, as we all do in this world. What’s amazing about her is that she adapted, at such a young age, and she survived her ordeal.