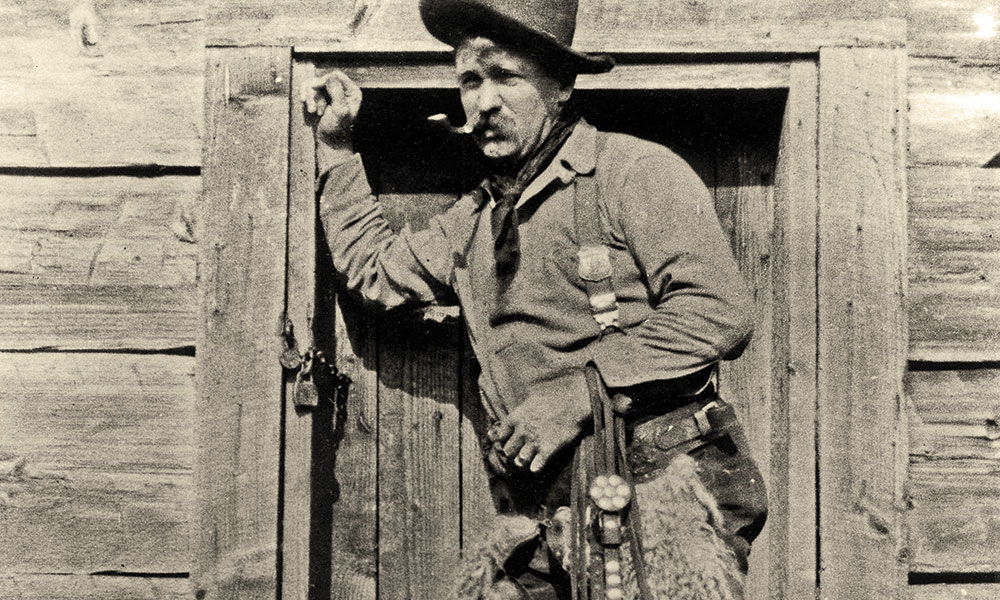

— Courtesy U.S. Forest Service —

Today, a forest ranger may call to mind a friendly guide who leads nature walks and gives campfire talks. But 100 years ago, forest rangers who worked west of the Mississippi River were closer in spirit and appearance to cowboys. During the early days of the U.S. Forest Service, these rangers rode horses, packed mules, and carried Colts and Winchesters. Their story is a little-told chapter in the history of the American West.

— All photos courtesy National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD unless otherwise noted —

Cowboys on the Forest Range

The Forest Service was created in 1905, when management of nearly 18 million acres of public lands was transferred from the Department of Interior’s General Land Office to the Department of Agriculture. These 17 forest reserves (later called national forests) were scattered across the U.S., with most in the Western states and territories.

Gifford Pinchot, a pal of President Theodore Roosevelt, oversaw the fledgling Forest Service. Pinchot’s vision produced the greatest good for the country. He balanced revenues brought in by timber sales, mining leases and grazing fees with conservation efforts.

Pinchot decided a graduate from Yale’s School of Forestry would supervise each reserve. District rangers took charge of subdivided parts of a forest, with assistant rangers reporting to them. Rangers carried out the day-to-day operations.

Given the strenuous work, rangers had to be between 21 and 40 years old. The starting pay was $60 monthly, and a ranger had to supply his own saddle, pack horses, tack, clothing, firearms, cooking gear, bedroll and other sundries.

Believing that the General Land Office had staffed the forests with political appointees, leading to incompetence and corruption, the country’s first Chief Forester kept the best General Land Office men and forced the rest out. For prospective rangers, Pinchot tasked his staff to develop examinations that would raise standards and encourage professionalism.

Self-Sufficient Men

Pinchot sought men familiar with the forests where they’d be working. Candidates were told: “No one may expect to pass the examination who is not already able to take care of himself and his horse in regions remote from settlement and supplies. He must be able to build trails and cabins and to pack in provisions without assistance. He must know something of surveying, estimating, and scaling timber, lumbering, and the live-stock business.”

The one-day written examination consisted of basic questions about timber cruising (assessing the potential value of trees), surveying, livestock care and local geography.

The more rigorous practical examination featured two-day field tests. Shooting was one of the first skills assessed. An early ranger recalled, “The applicants were required to shoot at marks at 100 yards with rifle and 50 yards with revolver.”

During the horsemanship portion, evaluator Elers Koch recalled, “Most of the men got by fairly well with the horseback riding, since everybody rode in those days, but from the way a man approached a horse and swung into the saddle it was not hard to tell the good horseman.”

Packing was another story. Prospective rangers had to cargo up a horse or mule with camp outfit and grub; this was not a skill everyone had. At times, examiners could barely keep a straight face, considering the curious knots, hitches and methods applicants used to attach gear to a horse.

The second day tested forestry skills. The men mounted horses and buggies, headed to the woods and were tested on ax work, timber cruising and surveying.

Koch concluded his ranger examinations with a hell-bent-for-leather, 10-mile horse race to Bozeman, Montana. An outstanding horseman, he never lost a race.

A Ranger’s Life

Once hired, men received their appointment to a forest district and were told to “go out and range.” They were expected to be self-starters. One man could have responsibility for a territory several hundred thousand acres in size.

Rangers took direction from a 142-page manual known as the “Use Book,” more formerly, The Use of National Forest Reserves: Regulations and Instructions. The thin volume spelled out how to deal with grazing, timber sales, trespass issues and fires. Between the Use Book and common sense, a ranger was expected to have the knowledge he needed to handle any situation he confronted.

“The ranger in his district was often the only policeman, fish and game warden, coroner, disaster rescuer, and doctor,” historian Robert J. Duhse wrote.

The job attracted rugged individualists, leaving no shortage of colorful characters. One included Montana ranger Fred Herrig, a big man with a thick handlebar mustache who had worked as one of Teddy Roosevelt’s Dakota Territory ranch hands and served as a Rough Rider in the Spanish-American War.

Herrig’s experience as a cowboy caused him to dress the part, down to his high-top boots with silver spurs. His dark bay horse wore a silver studded bridle, and his constant companion was his Russian wolfhound, Bruno. He favored a .45-70 rifle in his saddle scabbard and a .44 revolver on his belt—given to him by President Roosevelt.

Practicality and personal fashion dictated a ranger’s duds. A ranger only needed to keep his badge, a bronze medallion with a pine tree in the center, visible to the public.

A horse and maybe a buckboard wagon were a ranger’s primary means of transportation over trails or countryside, in those pre-road days. If a horse couldn’t survive the terrain or weather, a ranger set off on foot. He didn’t think much of strapping on a 25- to 40-pound pack and hiking 40 miles in summer or snowshoeing through deep snow in the dead of winter.

Lawmen Rangers

Encounters with bears, mountain lions and snakes were not unusual for rangers, but the pests who offered the biggest challenges were the two-legged variety, especially after the Forest Homestead Act of 1906. When homesteaders could claim a 160-acre parcel within forest boundaries, fraud became a big issue. Commercial timber, mining and grazing concerns paid people to file personal homestead claims, with an eye to acquiring the property cheaply after the claim was “proved up.” If a ranger suspected fraud, he gathered evidence to get the claim revoked.

Lawmen rangers didn’t sit well with homesteaders more interested in a quick buck than starting a new life, nor with ranchers, miners and timber men unhappy about conservation efforts. They occasionally threatened to hang or shoot the rangers.

Idaho rangers found trouble in Grand Forks, known as the “wickedest town in America,” while enforcing an alcohol ban. A dozen saloons and an undetermined number of brothels had sprung up there, to serve railroad construction crews.

One ranger, unable to convince soiled doves to leave, wired his supervisor, “Undesirable prostitutes occupying Federal land. Please advise.” The reply came back, “Get desirable ones.”

Even when rangers arrested the proprietors of vice and booze, replacements stepped in to run the show. Grand Forks ceased to be a problem in 1910, when the town burned to ashes.

Fighting Fire

A much greater threat than outlaws, though, were wildfires. During summer, fire was always on a ranger’s mind.

Down-on-their-luck men, often recruited from pool halls and saloons, typically made up firefighting crews of six to 75 men. Larger crews became necessary because “stewbums” were notorious idlers; while digging a fireline to corral a fire or beating flames out with burlap bags, a firefighting crew might feel the work had gotten too hard and walk off, never to be seen again.

A ranger would enforce his will with a shooting iron if a crew became unruly or panicked at an approaching wall of flames, as did “Big Ed” Pulaski, during the Great Fire of 1910, which burned three million acres and killed at least 87 people.

The 42-year-old former prospector knew Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains like the back of his hand. On August 19, Pulaski and another ranger were overseeing around 200 men fighting fires outside of Wallace. When hurricane-force winds struck, the smaller fires joined and turned into a raging inferno, trapping Pulaski and 42 men.

The ranger herded his panicked firefighters through the flames to a mine shaft. He ordered them to lay face down, where the air was cooler. Then he stationed himself at the entrance, fanning the flames away with a wet burlap sack.

When smoke filled the shaft, one man decided he’d take his chances outside. Pulaski drew his .44 revolver. “The next man who tries to leave the tunnel, I will shoot,” he proclaimed. He knew the tunnel was their only chance for survival.

Nobody else attempted escape, but the smoke and heat became so intense, everyone passed out from a lack of oxygen. When the fire died down and the men regained consciousness, they found Pulaski in a crumpled heap.

“The boss is dead,” one man said grimly.

“Like hell he is,” said Pulaski, as he struggled to his feet.

His hands, eyes and lungs seared, Pulaski was hospitalized, but recovered and returned to work. Hailed as a hero for saving his men, he is still known by wildland firefighters. The combination axe-mattock he created in his blacksmith shop a year after the fire is widely used and is called the Pulaski.

End of an Era

The cowboy rangers who rode the Old West’s forests lasted into the 1920s. Then telephones connected ranger stations and fire lookouts, wireless radios conveyed messages in the wild, fire roads crisscrossed the forests, cars and trucks replaced horses and wagons, and airplanes patrolled woods and range.

Instead of the Use Book, rangers had to consult a bookshelf full of policies. They grumbled about doing paperwork behind a desk instead of working outside. The jack-of-all-trades rangers saw their duties reduced, as job specialization became common.

In less than two decades, the time had passed for rangers with strong backs and steel wills. A Forest Service supervisor some 70 years ago best summed up these cowboy rangers: “They endured physical discomfort and hardships as a matter of course. Too often they had to face injustice and to battle discouragement, but they were never quitters.”

Saddle Up

While the days of the cowboy rangers are long gone, you can still get a taste of the old times at the Forest Service’s Ninemile Wildlands Training Center on the Lolo National Forest. Located outside Huson, Montana, the center features the Remount Depot, a facility built in the 1930s for pack stock breeding and training. The depot is a working ranch that, each summer, provides training to agency personnel and the general public on traditional ranger skills, such as packing, horsemanship, dutch oven cooking and tree cutting.

A former U.S. Forest Service firefighter, Joel McNamara has written magazine articles as well as technical books, including Geocaching for Dummies. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and specializes in American West historical archaeology.