— Courtesy A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art, Trinidad, CO —

A large rodent determined the destiny of Kit Carson, the Mountain Men and much of the American West. The North American beaver, the second-largest rodent in the world, along with its Eurasian cousin, was prized for its luxurious fur. Beaver pelts, useful in manufacturing malleable felts for hats, were prized throughout Europe, with the industry centralized in Russia from the 15th century onward.

The fine quality of beaver hats, and their expense, led to their identification with wealth. During the English Civil War, the broad-brimmed beaver hat became symbolic of the royalist cavalier faction, while in the Catholic Church, it became the headgear of cardinals. By the late 16th century, however, European beavers had been trapped to near-extinction.

The colonization of the New World opened up a fresh and cheaper supply of beaver pelts. The French and the British fought a series of wars in order to monopolize this new fur trade market. The triumphant British attempted to keep their American colonies hemmed in to the east of the Appalachian Mountains to better control this valuable trade, which contributed to the outbreak of revolution in 1775.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

With an increased supply of high-quality beaver pelts from America and the introduction of demi-castors (half-beaver pelts mixed with wool or hare), the price dropped and markets expanded throughout Europe and the colonies.

Now affordable to most consumers, hats were worn by everyone, in styles ranging from the top hat to clerical and military headgear that included the naval cocked hat, the tricorne and the army shako. In this era of almost-constant warfare, the English dominated the military headgear trade after 1750—it was big business.

The new American government looked to the frontier fur trade as a critical source for economic growth. When Thomas Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark westward in 1803, the explorers were charged with ascertaining the potential of the fur trade beyond the Missouri River. John Colter, one of the members of that expedition, would soon become famous for his exploits as a new type of frontiersman—the Mountain Man.

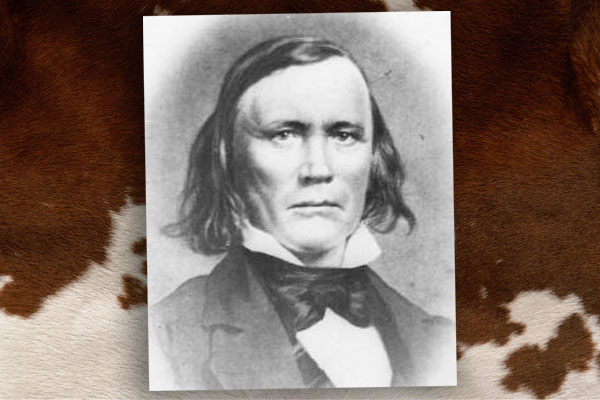

Yet the most famous of all the Mountain Men would be born on Christmas Eve in 1809 in Madison County, Kentucky—Christopher “Kit” Carson. But does his celebrity status mean Kit also deserves to be recognized as one of the kings of the fur trade?

Runaway Teen Kills His First Man

When Kit was two, his parents, Lindsey and Rebecca Carson, moved their family of 11 children westward in 1811, following Daniel Boone’s trail to Boon’s Lick, in Howard County, Missouri. Lindsey was killed in an accident while clearing out trees in 1818. Three years later, after Rebecca remarried, she apprenticed 12-year-old Kit to David Workman in nearby Old Franklin. The boy was to learn the saddler’s trade.

Workman was a kind master, but Kit was unhappy with the labor. He later stated, “being anxious to travel for the purpose of seeing different countries, I concluded to join the first party for the Rocky Mts.”

Old Franklin was an outfitting center for wagon trains heading west over the Santa Fe Trail. In August 1826, Kit joined William Wolfskill and Andrew Broadus’s caravan bound for Santa Fe in present-day New Mexico. Workman placed a one-cent reward for the runaway in the October 6, 1826, Missouri Intelligencer: “Notice is hereby given to all persons, that Christopher Carson, a boy about 16 years old, small of his age, but thick-set; light hair, ran away from the subscriber, living in Franklin, Howard County, Missouri, to whom he had been bound to learn the saddler’s trade…. All persons are notified not to harbor, support, or assist said boy under penalty of the law.”

The teenager reached Santa Fe that November and immediately headed north to Taos, then the seat of the Southwestern fur trade. He wintered there with Matthew Kinkead, a trapper who was also from Boon’s Lick. In the spring, Kit joined on as a teamster for an El Paso, Texas-bound wagon train. Back in Taos, Kit met Ewing Young, famed for his daring trapping expeditions throughout the Southwest. Young employed Kit as a cook, but soon promoted him to trapper.

— Courtesy Tim Peterson Family Collection, Scottsdale’s Museum of the West —

From Young, Carson learned not only how to be a trapper, but also the cruel reality of life on the far-flung edges of the frontier. In the spring of 1829, he accompanied Young and 40 other trappers on a dangerous journey to trap beaver along the headwaters of Gila River. This was Apache country, and the trappers had to dodge Mexican Army patrols—fur trapping by Americans was illegal—as well as Apache scouts.

American trappers were notorious for bribing Apaches with powder and guns for safe passage, yet Young declined to do so. Along the Salt River, Apaches attacked, but he and his trappers repulsed their foe. In this fight, 19-year-old Kit killed his first man. As was the trapper’s custom, Kit scalped the Apache.

As Young’s party pushed westward to trap along the Verde River, various American Indian bands continually harassed them. In frustration, Young sent a party of men to Taos with beaver pelts secured thus far, while he headed to present-day California with Kit and 16 others to seek safer trapping country.

A difficult journey followed in which their passage was blocked by the Grand Canyon. A band of Mojaves, who traded corn and beans with the trappers, guided them south to a crossing of the Colorado River. This same river crossing is where Mojaves had slaughtered most of Jedediah Smith’s trappers two summers before.

Young’s party reached San Gabriel Mission (near present-day Los Angeles) and turned north to trap the central valley of present-day California before returning to Taos in present-day New Mexico with 2,000 pounds of beaver pelts in April 1831. This was the first party of Americans to cross from the Rio Grande settlements to present-day California and then back again. In this epic journey, Kit became a full-fledged member of that daring and eccentric breed who came to be called Mountain Men.

Trapping with Broken Hand

In the autumn of 1831, Kit signed on with Thomas Fitzpatrick, one of the heads of the new Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Called “Broken Hand” by Indians because of a gunshot wound to his left wrist, Fitzpatrick had immigrated to America from County Cavan, Ireland, in 1816 at age 17. He traveled up the Missouri in 1823 with William Henry Ashley’s company—a band that included Jed Smith, Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, William Sublette and James Clyman. Some of these men were already on the Yellowstone with Ashley’s partner, Maj. Andrew Henry. Fitzpatrick took part in the great battle with the Arikara that June on the Missouri, in which a dozen trappers were killed and as many more wounded.

Many trappers pulled out of the trade after Ashley’s fight, but Fitzpatrick—along with Smith, Sublette, Clyman, Edward Rose and six other bold adventurers—decided to bypass the river route and strike westward to find a pass across the mountains and open up a land route between St. Louis, Missouri, and the rich beaver country on the far side of the Continental Divide.

The party crossed the Black Hills and made for Absaraka, the land of the Crows. Rose, who was intimate with the Crows, went ahead to meet with his friends. While he was gone, Smith was horribly mauled by a grizzly bear along the Cheyenne River. His detached scalp and dangling right ear were stitched back on by Clyman.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Fitzpatrick went ahead with most of the men to trap along the branches of the Powder River, while two stayed behind to nurse Smith. The party, eventually rejoined by Smith, then wintered with the Crows just north of present-day Wyoming’s Wind River Valley.

The Crows told their guests that the beaver were so plentiful in the Green River to the south that they would not need traps, but could club them. The trappers headed south in February to find this beaver Eden and, after an arduous journey, rediscovered South Pass. Others had been there before—most notably the eastbound Astorians led by Robert Stuart in 1812—but the Smith-Fitzpatrick party put South Pass on the map. In time, South Pass became the key point on the great road of Western empire.

The party trapped with great success. Smith and some of the men remained in the mountains, while Fitzpatrick carried their beaver pelts to Fort Atkinson, along the Missouri in present-day Nebraska, and reported the discovery of South Pass to Ashley.

When Fitzpatrick led Ashley and a party of trappers back into the mountains, Ashley divided the trappers into smaller parties and marked a spot along the present-day Utah-Wyoming border (at the mouth of Henry’s Fork of the Green) where they would all meet at the end of their hunts. The result was the first great Mountain Man rendezvous, held on the Green River in July 1825. Some 120 men attended this first of 16 such mountain fairs. Most were Ashley-Henry trappers who included Fitzpatrick, Clyman and Smith, but 20 Hudson Bay Company deserters joined in, as did a band of trappers up from Taos under

Étienne Provost.

At that first rendezvous, Ashley hauled in 9,000 pounds of beaver pelts, worth $50,000 in St. Louis, Missouri ($1.25 million in today’s money). Beaver skins traded for around $5 each. In comparison, coffee or sugar traded for $2 a pint, gunpowder $2 a pint, lead $1 a bar, tobacco $2 per pound, a good knife $2.50, while a blanket was $20. Whiskey was not plentiful at this first rendezvous, but that would change.

After the 1826 rendezvous, held in Cache Valley in present-day Utah, Ashley sold out to Smith, Sublette and David Jackson. Smith then led expeditions southwest from present-day Utah into California, where he trapped north up the San Joaquin to the American River and then east across the Sierra Nevada to reach the 1827 rendezvous at Bear Lake in present-day Utah. His remarkable expeditions made the teetotaling, bible-reading Smith a legend in the mountains.

In 1830, Smith sold out to Fitzpatrick, Bridger and three others, who formed the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. This is the outfit that Kit signed on with in 1831.

After purchasing the fur company, Fitzpatrick traveled to Santa Fe, in present-day New Mexico, with Smith, Jackson and Sublette. He needed to secure trade goods to take back to his men in the mountains. Smith, who had decided to quit the mountains after so many narrow escapes, was killed by Comanches along the Cimarron that May.

Late in July 1831, Fitzpatrick and some 40 men, including Kit, headed north up the front range to the North Platte and then west toward the Green River Rendezvous. Fitzpatrick soon returned to St. Louis, Missouri, but Kit and the others trapped the Green and then wintered in Idaho Country near the headwaters of the Salmon River. With the thaw, Kit and a handful of companions moved east to trap the central Colorado streams, where they had several sharp engagements with natives, endured considerable privation and hardship, but still returned to Taos in New Mexico country in October 1833 laden down with fur.

Trapping was, needless to say, hard and dangerous work. Kit’s friend Joe Meek left a clear account of the techniques employed by the trappers:

“[The trapper] has an ordinary steel trap weighing five pounds, attached to a chain five feet long, with a swivel and ring at the end, which plays round what is called the float, a dry stick of wood, about six feet long. The trapper wades out into the stream, which is shallow, and cuts with his knife a bed for the trap, five or six inches under water.

“He then takes the float out the whole length of the chain in the direction of the centre of the stream, and drives it into the mud, so fast that the beaver cannot draw it out; at the same time tying the other end by a thong to the bank. A small stick or twig, dipped in musk or castor serves for bait, and is placed so as to hang directly above the trap, which is now set.

“The trapper then throws water plentifully over the adjacent bank to conceal any foot prints or scent by which the beaver would be alarmed, and going to some distance wades out of the stream.”

The trappers skinned the beavers after removing from the trap (if the trap worked properly, the beavers had drowned). They discarded the meat and harvested only the pelt and castor glands for future bait. They kept the beaver tail too, considered a delicacy in the mountains.

The mountains were becoming crowded. Britain’s Hudson’s Bay Company ruled the far northwest. Their trappers pushed south into the central Rockies with the goal of trapping out the beaver and keeping Americans from coming north. Empire was at stake as well as money. The Americans had no such monopoly, for rival free trappers competed with the men of Fitzpatrick’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company and John Jacob Astor’s older American Fur Company for furs.

In this reckless enterprise, the beaver population was soon destroyed, as was the self-sufficiency of the natives. The diseases inadvertently introduced by the trappers also decimated the Indian population, especially among the river tribes. Astor, who operated several important fur trading posts in competition with the St. Louis trappers, came to dominate the trade. He made a fortune, but wisely left the business in 1834, just before its rapid decline.

Kit remembered his youthful years as a Mountain Man as the happiest days of his life. In March 1834, he rejoined Fitzpatrick and Bridger in northwestern Colorado. Although he was a free trapper, he agreed to work with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

While out hunting alone late one afternoon, Kit shot an elk, but almost immediately was confronted by two grizzly bears who seemed to desire a two-course dinner of both hunter and elk. With no time to reload, Kit ran for his life and climbed a tree. The bears could not climb the tree, but one remained a while to study Kit. “He finally concluded to leave,” Kit recalled, “of which I was heartily pleased, never having been so scared in my life.”

Bears might well have been Kit’s most terrifying foe that trapping season, but the Blackfeet also made life miserable for the trappers. In February 1835, Kit was shot through the shoulder in a fight with the Blackfeet along present-day Idaho’s Snake River. He recovered well enough to join Bridger in a spring hunt before heading to the Green River Rendezvous. Although that spring hunt was successful, it damaged the future of the Mountain Men by killing beaver mothers before they could nurture their kits (baby beavers who remained in the lodge for the first month of life).

— Courtesy Tim Peterson Family Collection, Scottsdale’s Museum of the West —

A Grand Rendezvous

The August 1835 Green River Rendezvous was to be one of the last of the great Mountain Men gatherings—and also its most notable. Lucien Fontenelle had departed from what would become Bellevue, Nebraska, in late June with six wagons, roughly 50 men and nearly 200 horses, and, on July 26, met up with Fitzpatrick at Fort William along the Laramie River (the future Fort Laramie). He had with him two Presbyterian missionaries—Dr. Marcus Whitman and the Rev. Samuel Parker—bound for Oregon Country. Under Fitzpatrick’s command, the party set out on August 1 and reached the Green River Rendezvous 11 days later.

Roughly 200 Mountain Men came, along with bands of Arapahos, Shoshones, Nez Perces, Flatheads and Utes. All attention was quickly riveted on Dr. Whitman, who demonstrated his great surgical skill by removing a three-inch iron arrow point from Bridger’s back. The Blackfoot barb had been lodged in Bridger for three years. Whitman, the hero of the hour, was now much sought after by many an ailing trapper in the camp.

Parker was delighted to find so many potential Indian converts at the Rendezvous, but he had no hope for the white heathens he found there: “They appear to have sought for a place where, as they would say, human nature is not oppressed by the tyranny of religion, and pleasure is not awed by the frown of virtue.”

Kit distracted the good reverend in a dramatic display of Mountain Men anger. “A hunter, who goes technically by the name of the great bully of the mountains, mounted his horse with a loaded rifle, and challenged any Frenchman, American, Spaniard, or Dutchman, to fight him in single combat,” the Reverend wrote. “Kit Carson, an American, told him if he wished to die, he would accept the challenge. Shunar [Chouinard] defied him—C. mounted his horse, and with a loaded pistol, rushed into close contact, and both almost at the same instant fired.”

Kit, who was slightly wounded above the ear, put a ball through his opponent Joseph Chouinard’s wrist that went up his arm before exiting. The wounded French trapper who worked for Astor’s company begged Kit for his life. Parker did not know that Kit and Chouinard

had previously quarreled over the affections of an Arapaho girl, Waanibe or Singing Grass, and that she had inspired their duel.

In good time, Kit would ask her father for the girl’s hand, pay a substantial bride price and take her away into the mountains.

With the Rendezvous winding down and most of the Indian bands departing, Fitzpatrick headed to Fort William with 120 beaver packs and 80 bundles of buffalo robes. More than 80 trappers accompanied him, for the beaver were playing out and trappers were quitting the business. Fitzpatrick was also joined by Dr. Whitman, returning east to recruit more missionaries.

Bridger guided the Rev. Parker toward Oregon Country, until he and his men reached Jackson Hole in present-day Wyoming to trap; Flatheads and Nez Perces conducted the missionary westward.

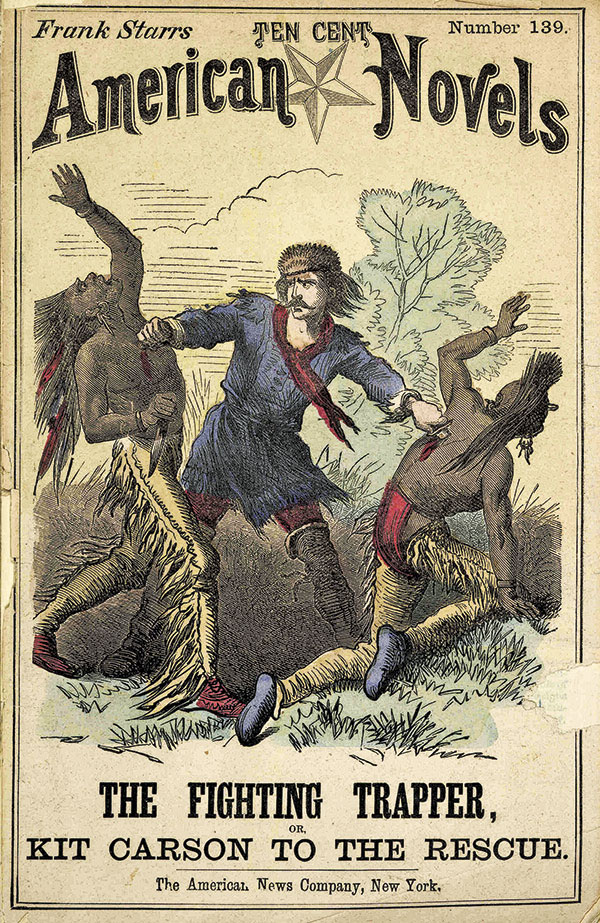

Parker explored Oregon country before he returned to the East coast by sailing ship via Hawaii and Cape Horn. His memoir of his adventures—Journal of an Exploring Tour Beyond the Rocky Mountains—published in New York in 1838, contained his account of Kit’s duel with Chouinard. This marked Kit’s first appearance in a book, but hardly the last.

Quitting the Mountains

By mid-September 1835, Kit was trapping with Bridger along the Yellowstone and Big Horn Rivers on the fall hunt. Kit even worked briefly for the Hudson’s Bay Company. The trappers found themselves constantly harassed by Blackfeet until the spring of 1837, when a smallpox epidemic reduced the once mighty tribe by two-thirds. The Mandans were almost completely wiped out. Astor’s men had inadvertently carried the pestilence up the Missouri River.

When Waanibe bore Kit a daughter, Adeline, they quit Blackfeet country and went south to Fort Davy Crockett at Brown’s Hole in present-day northwestern Colorado. Many of the Mountain Man marriages with Indian women were unions of economic convenience, but Kit and Waanibe were a real love match. Kit attempted to explain their devotion to each other to Jessie Benton Frémont, in simple Mountain Man terms: “But she was a good woman. I never came in from hunting but she had warm water for my feet.”

Waanibe bore Kit another child, in 1840, but became ill with fever and died from the complications of childbirth. A devastated Kit, with two small children to care for, decided to leave the mountains. “Beaver was getting scarce, and, finding it was necessary to try our hand at something else,” he later declared, some of us “concluded to start for Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas.”

Kit was warmly greeted at the trading post in 1841. Ceran St. Vrain and the Bent brothers offered him employment as a contract hunter, at $1 a day. The buffalo hide trade was quickly supplanting the beaver trade as the money maker. In Europe, the silk hat had come into favor, while the beaver hat fell out of fashion. By 1840, the beaver had been all but wiped out by the trappers anyway.

“Come, we are done with this life in the mountains—done with wading in beaver-dams, and freezing or starving alternately—done with Indian trading and Indian fighting,” Robert Newell told Joe Meek. “The fur trade is dead in the Rocky Mountains, and it is no place for us now, if ever it was.”

One by one, the trappers quit the mountains. The great era of the Mountain Men had come to an end. Many of these men, including Kit and Fitzpatrick, found work as guides for U.S. Army explorers and as Indian agents. Kit guided the famed “Pathfinder,” John C. Frémont, and that soldier’s report of their exploits made Kit the most famous frontiersman in America.

Was Kit the king of the Mountain Men, as later writers heralded him? Not at all. While Kit certainly deserved his reputation as a scout, Indian agent and soldier, he was never a leader of the Mountain Men. He came to the mountains late.

Young, Smith, Fitzpatrick, Sublette and Bridger were among the true leaders of that rare breed. Backing them, of course, were the men with the money—Astor, Ashley and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

All of them contributed to a bold enterprise that had blazed a trail across the wilderness that would soon give rise to a continental nation.

A Distinguished Professor of History at the University of New Mexico, Paul Andrew Hutton won the Western Writers of America Spur for his most recent book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History.