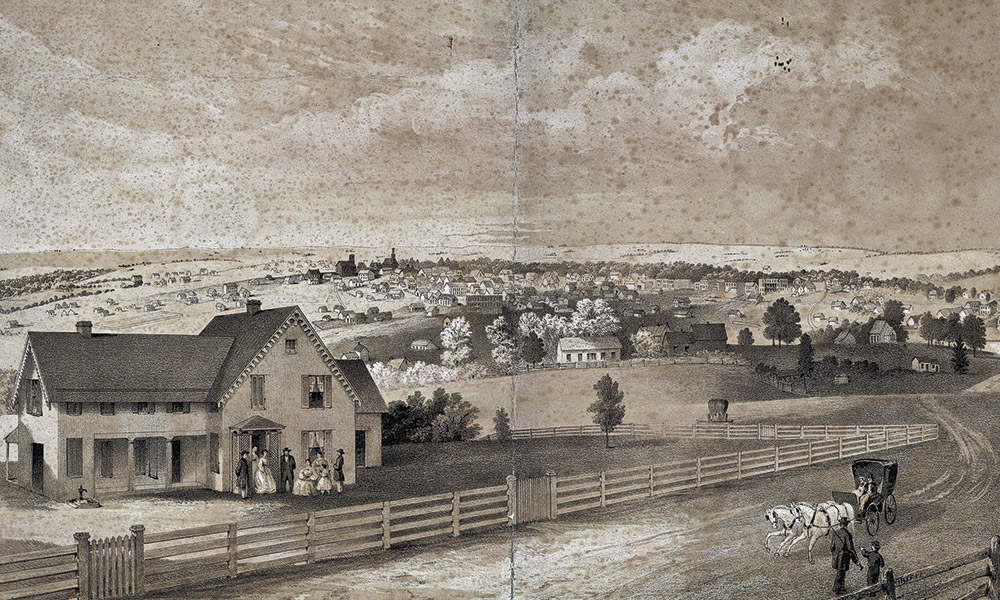

— Lithograph Nebraska City as seen from Kearney Heights by Alfred Edwards Mathews Nebraska City Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University —

Early law and order came not from lawmen, but citizens, in what is now Nebraska. When the wagon trains left Independence and St. Joseph, Missouri, pioneers crossed into a wild and unsettled territory. They called it, “Leaving the states.” Some traveled the overland trails to the newly discovered goldfields of California, while some wanted a new life in the West where land was plentiful. The emigrants left behind friends, relatives, business associates and a life regulated and protected by a system of laws and courts. Once the wagon trains were on their own, however, pioneers realized that punishment of crimes would be their responsibility alone.

The rigors of life on the trail soon began to wear on many emigrants. Every long day was full of strenuous activity. They were filthy, and hair and beards quickly became overgrown. Many travelers had never cared for animals, worked on wagons, slept on the ground or cooked over a campfire. Being constantly exposed to sun, wind, rain and storms added to stress on the trail. Sickness and death were not unknown. Indians were a constant concern. Emigrants quickly discovered that the hardships of the trail often brought out the worst in people. Profanity became common and more than one fight between traveling companions was recorded in letters and diaries. On one occasion, a doctor and his driver got into an argument and the doctor went after the man with a neck yoke. The unknown driver pulled a small caliber pistol and “…shot the doctor in the mouth, the charge coming out under his ear.”

Minor crimes that would have been misdemeanors in the states received only mediation. Trains were under a tight schedule to avoid being caught in the Sierras in winter, so they had to keep moving. Serious crimes such as murder, rape, theft of horses, were addressed formally. It was not unusual that a party was chosen to ride after the offender and return him to camp. The emigrants would choose a judge, form a jury and hold a trial to the standards they were familiar with. Punishments for these serious offenses included banishment from the train and hanging.

— Courtesy Nebraska Tourism —

The emigrants mistakenly expected that the Army would provide law-enforcement protection. A doctor at Fort Kearny on the Platte wrote, “The object of this garrison is said to be to overawe the Indians of this region of the U.S. Territories and thus protect the Emigrants.” The soldiers at Fort Kearny, for example, did not have jurisdiction over civilian criminal matters. In 1849, a man was killed by a blow from an axe. The man had tried to assault the wife of his traveling partner. The husband willingly returned to Fort Kearny for a hearing, presumably to exonerate himself. Without jurisdiction, the post commander held a type of administrative hearing to establish the facts, and the husband went on his way. The Army would only get involved in civilian offenses if they were committed at, or on the military reservation, or involved Army personnel and matériel.

Before beginning our tour, it is worthwhile to take a look at the Jesse James connections in Nebraska.

During the Civil War, Union troops look- ing for Southern sympathizers attacked the Missouri home of Jesse James’s mother, Zerelda, and husband, Dr. Rueben Samuel. The Samuels fled to Rulo, in the southeastern tip of Nebraska. In May of 1865, after riding with Quantrill’s Raiders, Jesse was shot in the chest at Liberty, Missouri. Brother Frank took the seriously wounded Jesse to Rulo so he could be treated by Dr. Samuel. The James trail in Nebraska includes Omaha, where Frank married Anni Ralston in 1874. Frank and Jesse made many visits to friends in Nebraska City, where Jesse’s famous portrait was taken in 1875. Frank James once drove a stagecoach from Nebraska City’s Arbor Lodge (home of J. Sterling Morton) to a local parade. It appears that Jesse was thinking about settling down in Nebraska. In 1881, the year before he was killed by Bob Ford, Jesse had answered an ad in the Lincoln newspaper that offered for sale 160 acres of land on the south edge of Franklin in south-central Nebraska. He’d signed the letter with his alias, Thomas Howard, 1318 Lafayette St., St. Joseph, Missouri.

— Chad Coppess —

We’ll begin our tour on northeast Nebraska’s official Outlaw Trail and Highway 12 Scenic Byway, which stretches 231 miles west to Valentine. The trail’s name reflects the rustlers, robbers and killers who plied their trade and found effective hideouts in the region. Lawmen were spread thin in this sparsely populated area and newly established courts often erred on the side of caution with convictions. It is believed that 58 people were lynched in Nebraska between 1859 and 1919. Many early daylight lynchings not only served as a warning to evildoers, but also were in response to ineffectual courts. Fear of escape was another reason swift “justice” was administered by vigilantes.

In 1870, Mat Miller was arrested after leaving the bloody corpse of his victim at the edge of Ponca. Citizens seized Miller from the sheriff and tried him by an “…orderly tribunal held in church.” Miller confessed and was marched straight outside where he was lynched. Ponca was a rowdy Missouri river port, but over time, the river channel edged east. Today, visitors will find Ponca State Park between the bustling historic town and the river.

In 1871, James Jameson murdered a man with an axe at St. Helena, just 45 minutes west of Ponca on Highway 12, and a short jog north. Jameson was arrested in Omaha and upon his arrival back in St. Helena, was promptly hanged. Only 13 years later, farmhand John Farberger was fired by his boss, the Cedar County sheriff. He burned the sheriff’s hay when he left and when arrested, shot and killed the sheriff’s deputy. A mob formed and dragged Farberger to the jail yard in St. Helena and lynched him.

Nebraska’s most famous outlaw, James M. Riley, alias David C. “Doc” Middleton, and his “Pony Boys” are largely the reason for the Outlaw Trail. The entire northern section of Nebraska was Middleton’s territory. A practiced Texas horse thief, killer and prison-escapee, Middleton came to Nebraska in 1876. He was not a doctor of medicine, but of altering (doctoring) horse brands. An altercation the following year at a Sidney dancehall left a soldier dead. On the run again, the outlaw perfected his horse-stealing abilities. He was caught with stolen horses by a posse near Julesburg, Colorado, and returned to Sidney, only to break jail. Even horses of the Poncas and Sioux weren’t safe. Once taken in and nursed back to health by an eastern Wyoming rancher, Middleton then stole horses from him as thanks.

— Photo of Blaine Hotel by Monty McCord —

Proceeding west on 12 a few miles west of Crofton, near Lindy, head north to look over Devil’s Nest, probably the largest outlaw hideout in the state. From a high ridge one can see the rough countryside that was a natural habitat for outlaws. Legend has it that after the Northfield, Minnesota, bank robbery, Frank and Jesse James hid here. Just ahead is the Lewis & Clark State Recreation Area and Missouri River.

The scenic Niobrara River adds natural beauty to the tour as we continue west to Lynch. Horse Thief Canyon is about six miles southeast, near the river. The landscape has not changed much so it’s easy to imagine Doc Middleton and his partner Kid Wade riding up out of the ravines.

After about a 90-minutes drive west, we turn south off 12 to Meadville. A restored general store and a couple of fallen-in buildings comprise the ghost town. Doc Middleton’s hidden horse corral was about six miles west on the south side of the Niobrara River.

An hour farther west on 12, we arrive in Valentine, established in 1883 when the railroad made it to that point. The rowdy element was usually just outside this cowtown at the hog ranch that attracted cowboys from South Dakota, Wyoming and Nebraska. The Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge and Wilderness Area near Valentine is home to buffalo, deer, elk, a prairie dog colony and over 200 bird species. Don’t miss the Cowboy Trail, Nebraska’s first state recreational trail. The former Chicago & Northwestern Railroad right-of-way is the nation’s longest rails-to-trails conversion, stretching 321 miles from Norfolk to Chadron. Walk or bike the old C & N railroad bridge that stands 150 feet over the Niobrara River at Valentine.

This ends the official Nebraska Outlaw Trail, but we’ll continue our tour west on Highway 20 to Merriman. The 1894 Bowring Ranch State Historical Park is located 1.5 miles north on Highway 61, and two miles east. A Hereford demonstration ranch, the historic home features fine antiques and memorabilia of former United States Senator Eve Bowring, who donated the ranch in honor of her husband, Arthur.

Still following the trail of David “Doc” Middleton, we travel through Gordon on our way to Chadron, about 75 miles west on 20. Doc’s luck finally ran out and he spent about three years in prison. His outlaw pal, the young Kid Wade, wasn’t so lucky. After being arrested a second time for horse theft, Wade was taken from officers and lynched about a mile east of Bassett.

Chadron was home to another member of the lawless fraternity. “Flat-Nose” George Currie moved with his family from Canada to Chadron when he was a child. He became a teenage rustler and later a member of the Wild Bunch, robbing banks and trains. Lawmen chased down Currie in Utah and killed him. He now resides in Greenwood Cemetery in Chadron.

Monty McCord is the author of Mundy’s Law and the 2018 follow-up, When I Die. His new book, Calling the Brands—Stock Detectives in the Wild West will be released July 1. He lives in Nebraska.