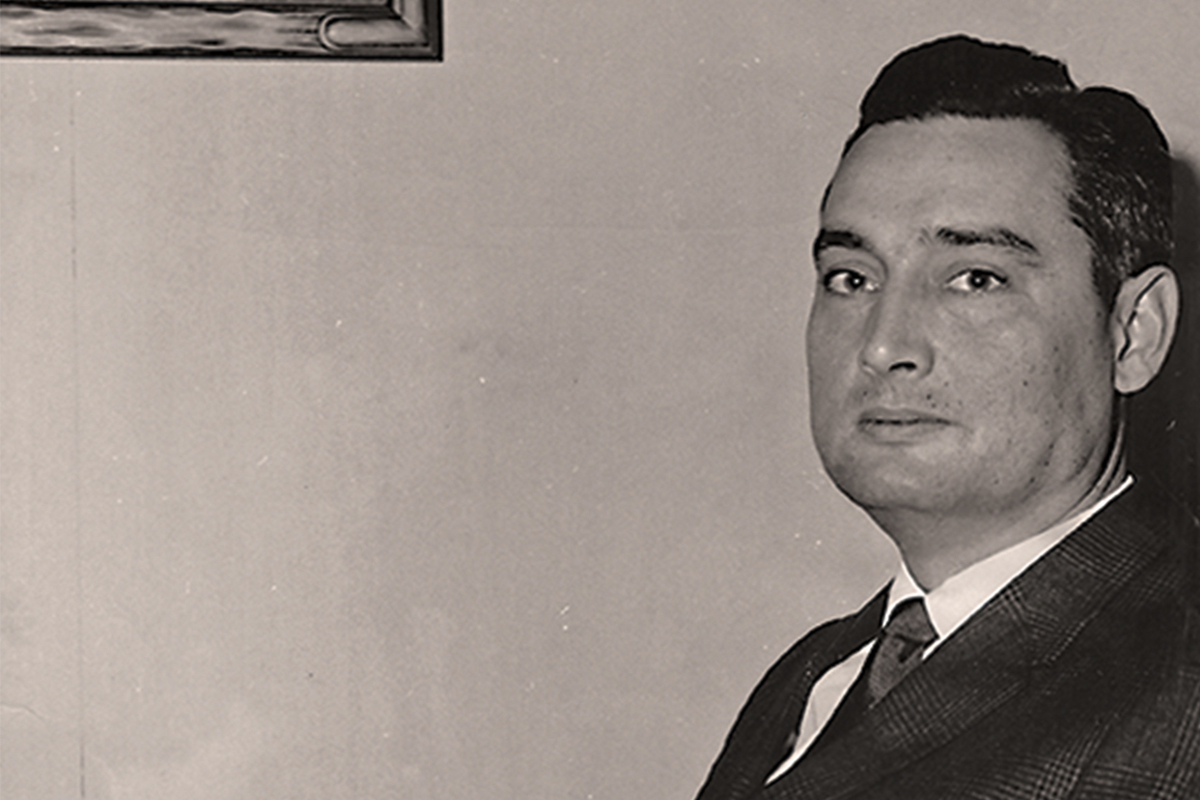

I first met Robert M. Utley in May 1977. He came to Bloomington to receive a Distinguished Alumni Service Award from Indiana University. I was a graduate student in history at IU at that time, and as soon as I learned that Utley was coming to campus, I sought out my mentor, Martin Ridge, to beg for the opportunity to pick up our guest at the Indianapolis airport and deliver him back. I assured Ridge that I would positively die for the opportunity to meet Utley. He thought this but a slight ambition (and never tired of reminding me of it in later years), but agreed to allow me to play chauffer. This eventful meeting was—as Bogart said to Rains in Casablanca—the beginning of a beautiful friendship, as Utley became a surrogate father and professional champion for me across the nearly half century to follow.

The following year, I accepted a position as assistant editor of the Western Historical Quarterly at Utah State University. I later learned that Utley had written an unsolicited letter on my behalf to Prof. George Ellsworth, the WHQ editor, and that had sealed the deal for me. This position, in which I remained for seven years, gave me high visibility in Western history circles at a very young age. During this time Utley also carefully critiqued my dissertation on Gen. Phil Sheridan. His devastating assessment and wise edits sent me back to the drawing board. I rewrote the book along the lines he suggested (he thought it dreadfully dull and far too academic). The end result—Phil Sheridan and His Army—won not only a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America but also the prestigious Ray Allen Billington Prize from the Organization of American Historians. My career was firmly set in the worlds of both academic and popular Western writing, thanks to Bob Utley.

In 1984, I accepted a teaching position at the University of New Mexico, and not long afterward moved to Eldorado, just outside Santa Fe, where Bob lived. We often debated history points as he worked on his books, with me urging him to be a bit tougher on his hero, Custer, in Cavalier in Buckskin and to cut my hero, Billy, a break in his Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Even though he once barked at me in exasperation that “all you sixties hippies think young people don’t have to take responsibility for any of their actions!” he nevertheless dedicated Billy the Kid to me. It was quite daunting to watch his incredible productivity in those years.

In these years as neighbors, Bob and I often travelled together to history meetings. None was more memorable than our overland expedition from Santa Fe to Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1989, to attend the annual Little Big Horn Associates conference. John Carroll was the Grand Poobah of the LBHA, and he had especially urged Bob to attend, for he was certain that Cavalier in Buckskin would win the best Custer book prize that year. As we made the long drive from Santa Fe to Fort Riley, Bob gently lectured me on the importance of going to accept awards—no matter how obscure they might be. It was wonderful to bask in the glow of his noblesse oblige and to feel warmed by his willingness to travel so many miles to reward the Custer buffs for their generosity with a personal appearance. Carroll had arranged for Bob to give the banquet address to the several hundred attendees, so he could be seated at the head table when the best book award was announced. I sat in the back of the room with friends and was rather surprised at the tepid response to Bob’s address. Many of the Custer buffs were uncomfortable with Bob’s candid comments on Custer’s marital infidelities, for they did not wish to see their hero descend from his marble pedestal to the level of the rest of humanity. I sensed trouble. When the best book award was announced, Bob was almost out of his seat before he realized it had gone to a book on the day-by-day movement of the 7th Cavalry from Reconstruction duty in Kentucky to North Dakota in 1873. The next morning a chagrined John Carroll bade us farewell as we began the long drive back to Santa Fe. It was a pretty quiet drive, but somewhere near Wagon Mound, New Mexico, I suddenly became convulsed with laughter. Utley was not amused and inquired of what so tickled me (although that was not the exact language he employed). Well, I replied, I was delighted to have finally come to clearly understand the meaning of the ending of one of my favorite films—John Huston’s Treasure of the Sierra Madre. At the end of the film, the surviving protagonists are convulsed with laughter, despite the loss of both companions and treasure, as they realize the insanity of their own hubris. Our friends in the LBHA had just taught us that valuable lesson—one that our hero, Custer, only learned in the last hour of his life. We laughed all the way back to Santa Fe.

Many trips, many awards, and many television shows together followed, but none could ever quite match that magical trip to Fort Riley, Kansas. Ten years ago, I hosted a surprise 80th birthday party for Bob in Scottsdale with many of his friends and protégés in attendance and repeated that in 2020 for his 90th birthday. I plan to do the same in 2029 for his 100th. Now I worry a bit that I may not make it, but I have no doubt that the indestructible Robert M. Utley—the Old Bison—will be there.

University of New Mexico Distinguished Professor of History Paul Andrew Hutton is the author or editor of a dozen books, including the award-winning Phil Sheridan and His Army and The Apache Wars. He is currently writing a history of the American frontier movement, The Undiscovered Country, to be published by Dutton/ Random House.