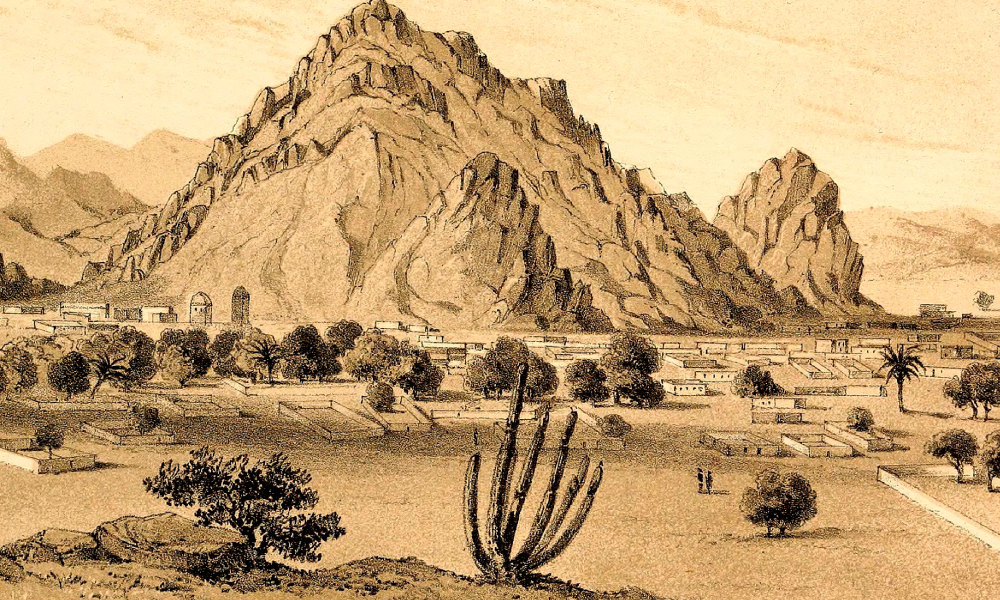

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

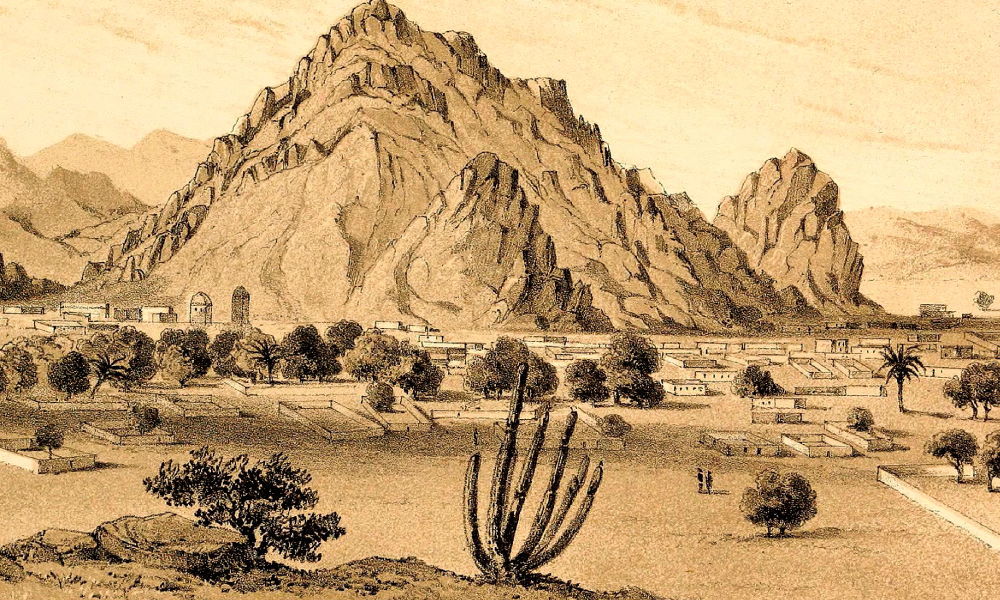

Over the years—and we’re talking many years—it went by several names: Sonora Road, Kearny Trail, Gila Trail, Butterfield Stage Trail, Old Gila Trail, Fort Yuma Road, Southern Route, Emigrant Road/Trail, Southern Emigrant Trail. And, for a while, it probably had no name at all.

The Old Gila Trail (we like that name; sounds like a Stan Jones song) stretched from…well…points east to California. Since artifacts that date back at least 15,000 years have been found along the route, some historians will argue that this is the oldest major trail in the U.S., and crosses, as historian Hampton Sides put it, “some of the most infernal country imaginable.”

This being desert, the trail followed mostly rivers—the San Pedro, the Gila. It stretched from Texas, or Santa Fe, New Mexico (that one became Cooke’s Road when Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke led wagons and the Mormon Battalion south and west during the Mexican-American War), traversed southern New Mexico and southern Arizona, and then on to San Diego or Los Angeles.

The first non-Indian man to follow the trail was a black slave named Esteban, who led a Franciscan monk in search of the Seven Cities of Cibola in 1538. Fur trappers traveled along it as early as the mid-1820s. Major Lawrence P. Graham led Dragoons along the way in 1848. Forty-niners followed it to California during the Gold Rush. A railroad survey expedition came along in 1855, and John Butterfield sent his stagecoaches along it

just before the Civil War. James Carleton led the Union’s California Column across it during the Civil War.

It wasn’t exactly like traveling across Interstate 10. As Cooke wrote: “Half of

[the expedition] has been through a wilderness where nothing but savages and wild beasts are found, or deserts where, for want of water, there is no living creature.…Marching half naked and half fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made a road of great value to our country.”

For our purposes, we’ll consider those displaced disillusioned emigrants, from North and South, who took the journey after the Civil War. And start it east of El Paso at Hueco Tanks.

El Paso

Travelers heading west likely would have stopped here because the natural “tanks” often held water—one reason Butterfield set up a relay station here. Actually people have been stopping at the tanks for food, water and shelter for some 10,000 years. Today they come for rock-climbing or to admire the pictographs and petroglyphs. Although a state park and historic site, there are only 20 campsites, and access to the North Mountain area is limited to 70 people.

More people are allowed in El Paso, especially Concordia Cemetery, where 60,000-plus people are buried—including post-Civil War outlaw John Wesley Hardin; Confederate veteran-turned-John Wesley Hardin slayer John Selman, whose grave has not been located; Texas Rangers; Buffalo Soldiers; and many more.

Even by the time the railroad arrived in 1881, El Paso was “little more than a collection of shacks baked to a dusty brown by a hot sun,” Odie B. Faulk wrote. It’s still mostly dusty brown, but it’s not all shacks, and its boot factory outlets can outfit you for travels West.

Land of Entrapment

After the Civil War, cattle crossed the Gila. Indians had ended most ranchers’ dreams in the 1850s, but, Faulk wrote, “with the return of soldiers and the creation of reservations, ranching could spread once again—for both soldiers and Indians, along with the miners, had to be fed.”

John Chisum came. So did others. We’ll single out two attorneys, Albert Jennings Fountain and Albert Bacon Fall. “Fall was a southerner,” historian Leon C. Metz wrote. “Fountain a Yankee.” Throw in a Texas gunman rancher named Oliver Lee, charges of rustling and a threat against prosecutor Fountain (“If you go on with it you will never reach home alive.”), and you have a great unsolved whodunit.

In 1896, Fountain and his eight-year-old son disappeared on their way home to Las Cruces from Lincoln after getting 32 rustling indictments from the grand jury. Three years later, lawman Pat Garrett was taken out of retirement to “solve” the mystery, while Jim Gilliland and Lee were tried in Hillsboro in an 18-day trial—basically Republican vs. Democrat—that led to the jury’s seven-minute deliberation and acquittal. The bodies have never been found.

– True West Archives –

In Las Cruces, check out the law enforcement museum at the Doña Ana County Sheriff’s Department and see Garrett’s grave in the Masonic Cemetery. Mesilla, once the gateway to southern New Mexico but now an art town, is always worth visiting. The Gadsden Museum in Mesilla, open by appointment only, is dedicated to Albert Fountain and his family.

Westward went the emigrants, of course. To Shakespeare, a silver-mining town founded in the 1870s where lawbreakers (or presumed lawbreakers) might be hanged inside the Grant House. Now a ghost town, Shakespeare offers tours. Checkout ShakespeareGhostTown.com for dates.

Bloody Arizona

Many moved into Arizona Territory, where Apaches made things difficult for ranchers—and anyone else—even after the Civil War.

“The title of ‘Dark and Bloody Ground’ never fairly belonged to Kentucky,” John G. Bourke wrote in On the Border With Crook. “Kentucky never was anything except a Sunday-school convention in comparison with Arizona, every mile of whose surface could tell its tale of horror….”

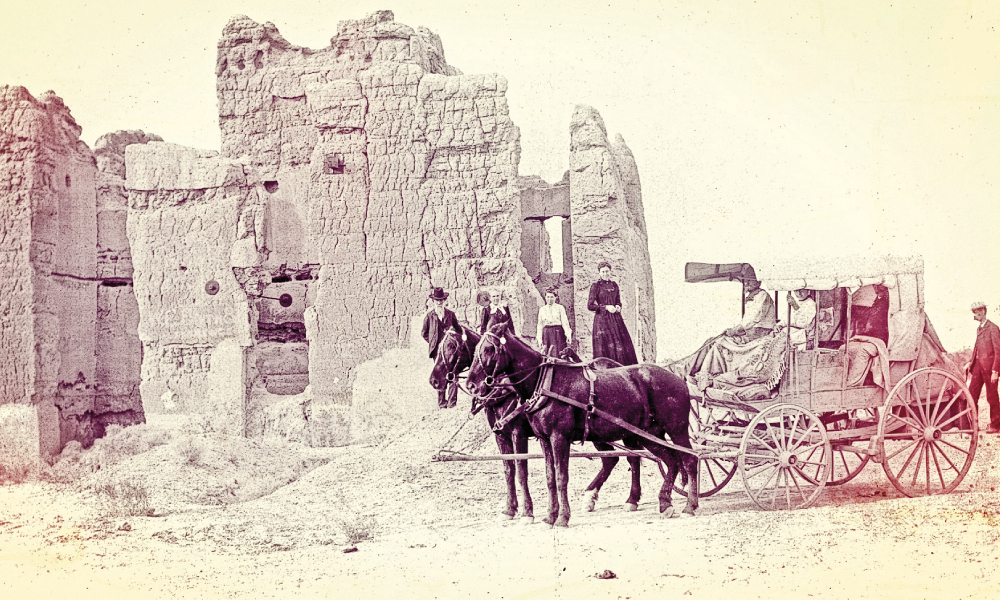

The museum at Fort Bowie, now a National Historic Site of mostly adobe ruins and the nearby graveyard, is a good place to start to learn why it took 20 years to bring relative peace to Arizona.

Henry Hooker didn’t found Arizona’s first permanent cattle ranch until 1872. Now a National Historic Landmark, Hooker’s Sierra Bonita Ranch remains in operation on private property in Coronado National Forest. But Hooker’s story is told at the Rex Allen Museum in Willcox, where Warren Earp (of that Earp family) was killed in a gunfight in 1900 with one of Hooker’s men and is buried in the Willcox Cemetery.

Travel south to Arizona’s “Dark and Bloody Ground” of Cochise Stronghold, the ghost town of Pearce, and Douglas, where Texas John Slaughter (born in Louisiana, not Texas) acquired the San Bernadino Ranch. His restored ranch, 16 miles east of Douglas, is open Wednesdays through Sundays.

Mining also grew in this violent country, especially after the Army removed the Chiricahua Apaches. Among the best to visit today are Bisbee and Tombstone. Bisbee came about because a civilian tracker found traces of valuable minerals on an Army scout

for Apaches in 1877. Tombstone got its name because, if you believe the legend, scout Al Sieber predicted that miner Ed Schieffelin would find his grave instead of silver.

Yet Apaches didn’t cause all the violence along the Gila Trail. Tombstone’s O.K. Corral is proof of that. Tombstone’s violence even reached Tucson, where Wyatt Earp shotgunned to death Frank Stilwell, a member of Tombstone’s Cowboy faction, in 1882. That event is memorialized at Tucson’s historic depot, where the Southern Arizona Transportation Museum offers another glimpse at the railroad years along the Old Gila.

West of Tucson, at what is now Picacho Peak State Park, Confederate and Union soldiers skirmished on April 15, 1862.

Keep going. To Casa Grande, for some of the earliest settlements on

the Old Gila Trail. To metropolitan Phoenix, where Scottsdale’s Guidon Books offers a treasure of Western history books. And where the Arizona Capitol Museum’s “Arizona Takes Shape” exhibition traces the Arizona history from the territory’s creation in 1863 to statehood in 1912. To Yuma, where Wyatt Earp didn’t wind up for murdering Frank Stilwell, but 3,040 other men and 29 women spent time during the territorial prison’s 33 years in business. It’s a state historic park.

– Carlo Gentile, ca. 1870, Library of Congress –

End of the line

And into California. To Julian, where in 1869 a former slave discovered gold in the Cuyamaca Mountains and set off another California gold rush, and where Joseph Treshil’s blacksmith shop has been turned into the Julian Pioneer Museum.

And to San Diego, where Wyatt Earp ran three gambling halls in what is now the city’s historic and funky Gaslamp Quarter.

The towns along the Old Gila have changed, of course. Some remain dusty brown, but most are cosmopolitan. Yet as Faulk once lamented, youngsters should “know that the spark of the telegraph and the lonesome whistle of a freight train at midnight are as much a part of the Southwest as is the asphalt and concrete of a superhighway. These are what made possible both the present and the future.”

Johnny D. Boggs and The Bride have decided that when they run out of money and have to leave Santa Fe, they’ll settle in Tucson.