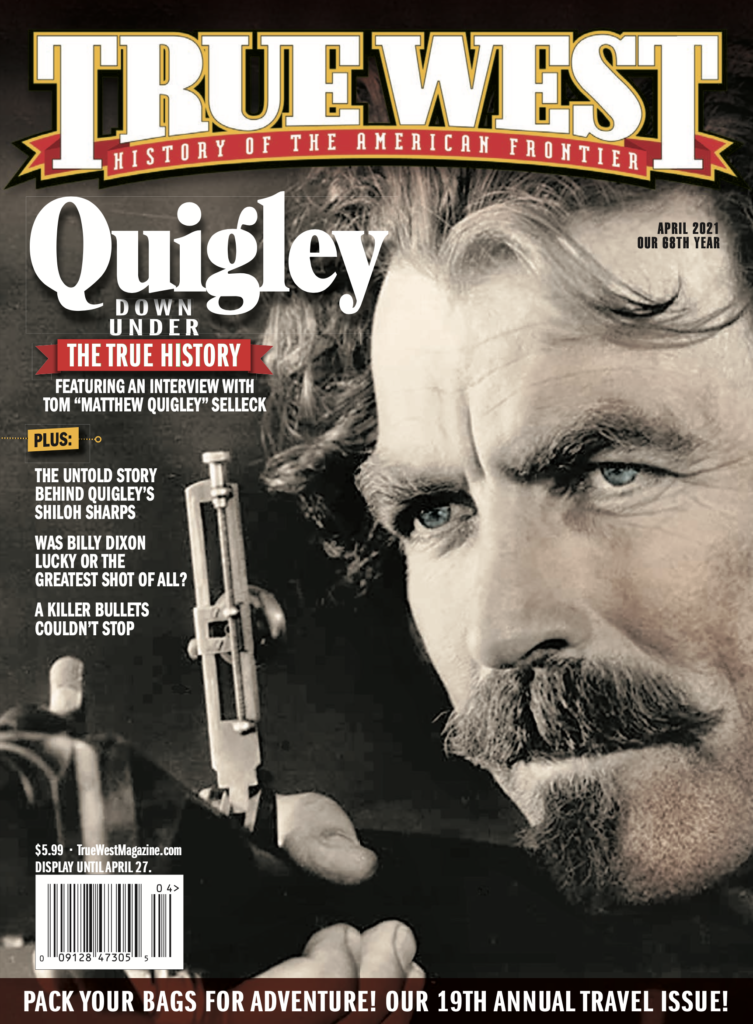

Quigley Down Under challenged the status quo of Western filmmaking in 1990, and it continues to inspire three decades later.

Thirty years ago, Dances with Wolves was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and was awarded 10 Oscars.

The film’s star, Kevin Costner, earned Oscars for direction and production, the first producer to accept a Best Picture Oscar for a Western film since Cimarron in 1931. Costner’s film, categorized as a revisionist versus traditional Western, was only one of a dozen big-screen or television Westerns released in the United States in 1990. Of those 12, only a third stand out critically: Wolves, Back to the Future III, Young Guns II and Quigley Down Under. Future III was, of course, a mash-up of science fiction, comedy and Western, while Young Guns II, ’the second installment in John Fusco’s highly successful and popular Billy the Kid series, was the most traditional Western of the year. Quigley Down Under, in its form, style and production, is as traditional as any Western before or since, yet it’s considered a revisionist Australian Western. And, compared to Dances With Wolves, Quigley Down Under was not a box office or major critical success.

So why is it that 30 years later, Quigley Down Under has overcome those box-office and critical disappointments to be considered the best Australian Western with one of the genre’s most beloved characters, Tom Selleck’s Matthew Quigley? And how did it develop a cult following of Western firearm aficionados?

Since its release in 1990, Quigley Down Under has become beloved by Western fans because of its outstanding production, direction, writing, cinematography and international cast, anchored by Tom Selleck in the title role. I believe the social issues it addresses with respect to the people and culture of the Australian Aboriginal people, and the injustices, violence and racial prejudice perpetrated on them during the frontier settlement of Australia, directly parallel the plot lines of its 1990 peer, Dances with Wolves.

Since their release, both Westerns have significantly influenced the American and Australian Western genre, with filmmakers from both countries continuing to address these topics on screen and casting more indigenous actors in their films. (For an in-depth profile of Selleck’s career in Westerns and his reflections on the themes of Quigley, see Henry Parke’s feature on page 26. For a history of Australian Westerns, read Parke’s column on page 64.)

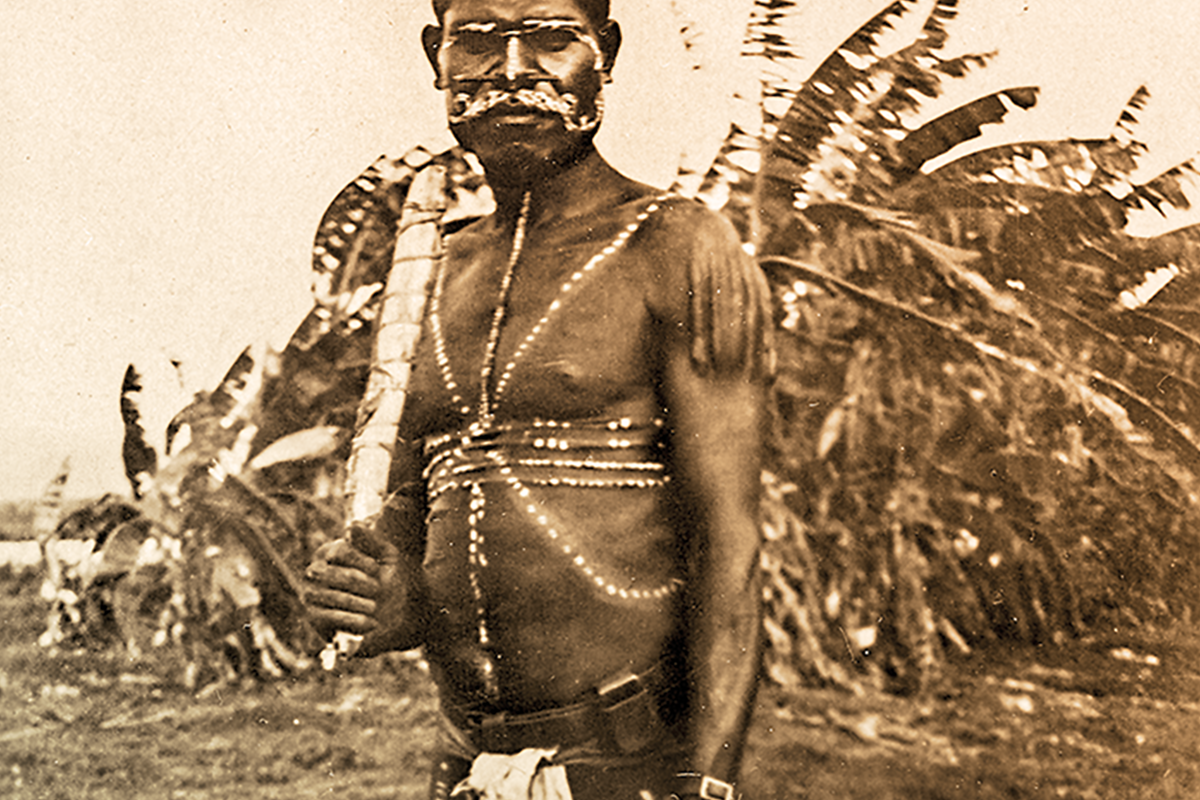

– AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINE, 1920, COURTESY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES, NORTHWEST TERRITORY –

Quigley has reached cult classic status because collectors and fans of traditional Old West firearms love the custom 1874 Shiloh Sharps rifle that Matthew Quigley carries and uses with deadly, highly accurate ferocity against the murderous oppressors of the Aboriginal Australians. The never- before-told history behind how the Sharps became the signature prop of the movie— and, possibly, the greatest Western cinema firearm (at the very least, the most popular rifle)—is explained in detail in Firearms Editor Phil Spangenberger’s exclusive “Shooting From the Hip” column on page 23.

But what of the real history behind Quigley Down Under? According to an October 19, 1990, interview in the Los Angeles Times, screenwriter John Hill, who passed away in 2017, was inspired to write Quigley in 1974 , after reading an article in the Times that “explored the genocide of Aborigines in the latter 1800s.” (Ironically, Dances with Wolves author Michael Blake was inspired to write his novel after reading Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, a bestselling and heartbreakingly truthful look at America’s Indian atrocities.)

Hill’s original screenplay for Quigley Down Under creatively takes a very controversial American subject, American Manifest Destiny, and transfers the complex and incendiary issues of racial violence and prejudice perpetuated against American Indians to Australia’s violent treatment of Aboriginal Australians.

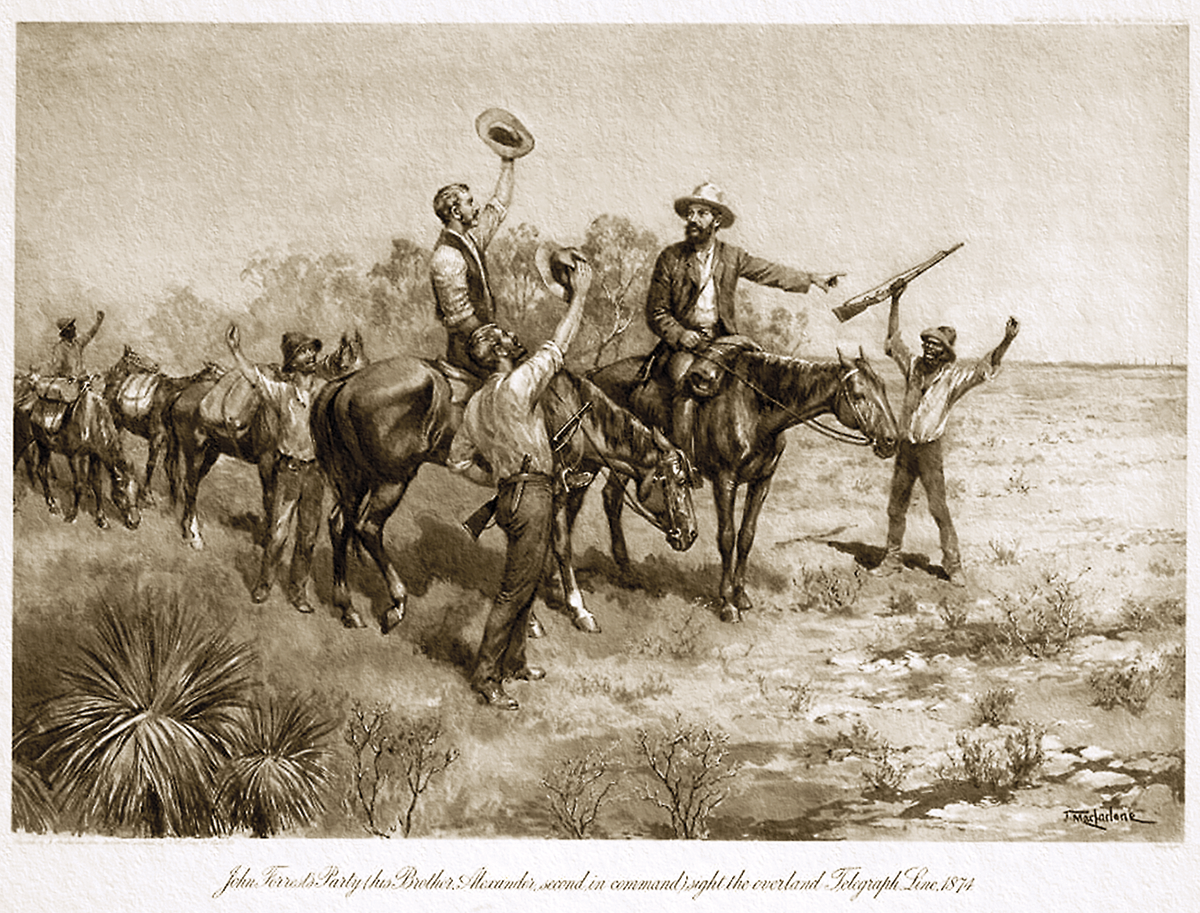

– “JOHN FORREST’S PARTY (HIS BROTHER, ALEXANDER, SECOND IN COMMAND) SIGHT THE OVERLAND TELEGRAPH LINE, 1874,” BY J. MACFARLANE, (GEO. ROBERTSON & CO., 189-?), COURTESY NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, 1403926208-1 –

Hill drops his hero, Wyoming cowboy Matthew Quigley, and an American prostitute, Crazy Cora, into Western Australia. In the mid-1870s, the Australian colonial and territorial government, military, police and settlers were broadening their control and conquest of the continent. And, like the American Indians, the Australian Aborigines were viewed with prejudice and considered a people without rights to their own land, despite their long occupation of it. It was seen as a wilderness ready for conquering and development.

Australian historian Chris Owen writes in his introduction to ‘Every Mother’s Son is Guilty’: Policing the Kimberley Frontier of Western Australia, 1882-1905, “The first European colonists viewed Western Australia through the prism of the doctrine terra nullius, as ‘unoccupied,’ despite the obvious presence of Aboriginal people.”

At the helm of Hill’s script, rightfully so, was Australian director Simon Wincer, who in 1990, was just off the successful production of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. Wincer nimbly and evocatively directed his international and native Aboriginal cast and crew—under laborious, harsh conditions—across Outback locations in Victoria, New South Wales, Central Australia and Northern Territory, including Alice Springs.

Filming Hill’s script, which is set during the tumultuous 1870s of Western Australia, across Australia’s Outback broadens the scope of the conflict between white Australians and Australia’s Aboriginal people living in the harsh conditions of frontier Australia, rather than in just one region. Northern Territory historian Darrell Lewis writes in his introduction to A Wild History: Life and Death on the Victoria River Frontier, “When the first settlers and cattle arrived in the Victoria River country, they were unarguably in a frontier situation. For the next 20 years this frontier was characterized by violent conflict with the Aborigines, extreme isolation, desperately slow communication, and rough living and working conditions.”

Today, three decades after Wincer, Selleck, crew and cast went on location into Australia’s Outback to film Quigley Down Under, the dramatized history remains as poignant and heartbreaking as the real history that Australians and Americans still struggle to confront and accept. The road to greater understanding, honest acceptance and mutual respect for our shared history, Australian and American, has been fraught with difficult truthful conversations about our violent and prejudicial past and present. As Australian Guardian feature writers Lorena Allam and Nick Evershed recently wrote in their special report on the frontier wars of Indigenous Australia, “The truth of Australia’s history has long been hiding in plain sight.”

Fortunately for all of us, filmmakers sometimes see those stories even before the historians do, and through their dramatic license jump-start the uncomfortable conversation and inject it into the public forum for further and more provocative investigation.