– Courtesy of John Langellier

and Bob Boze Bell –

After four years of fighting, the Civil War ended. The victorious Union Army soon disbanded, leaving behind a small force of regulars to such diverse duties as guarding the Eastern Seaboard, serving as an occupation force in the South during Reconstruction, and returning to its numerous functions in the West. The work in the West often proved frustrating, especially because after Lee’s surrender the authorized strength of the U.S. Army shrank to 54,302 officers and men, while the salary of a private was decreased three dollars per month, which represented nearly a 20 percent reduction in pay. Matters worsened over time. From the mid-1860s through the late 1890s, the actual total force of the regular Army averaged a scant 25,000 men.

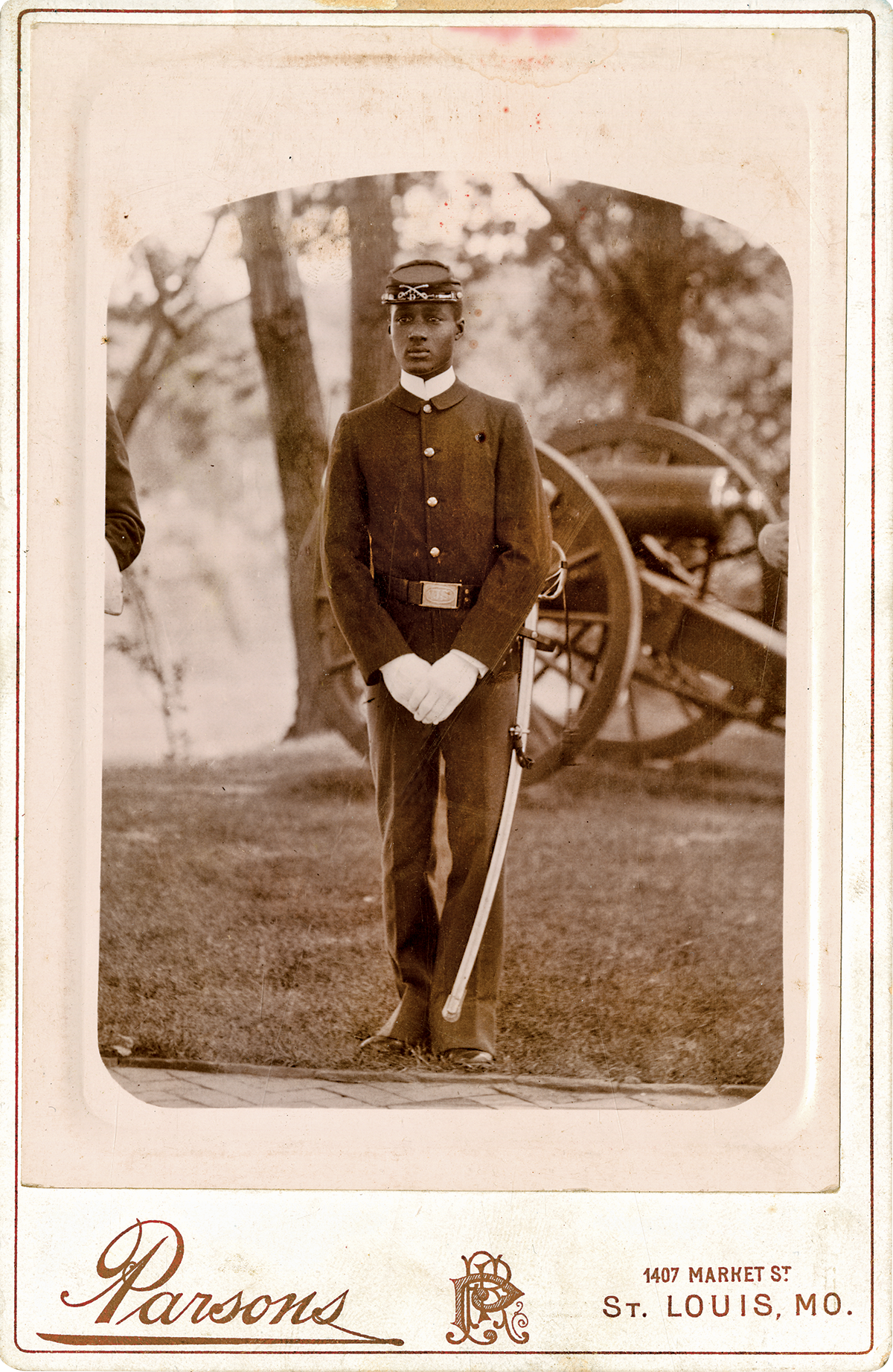

Among these frontiersmen in blue were new additions. For the first time the rank and file included African Americans, many of the earliest recruits having been enslaved prior to joining the colors. Eventually they came to be known as buffalo soldiers.

– All Images Courtesy John Langellier Unless Otherwise Noted –

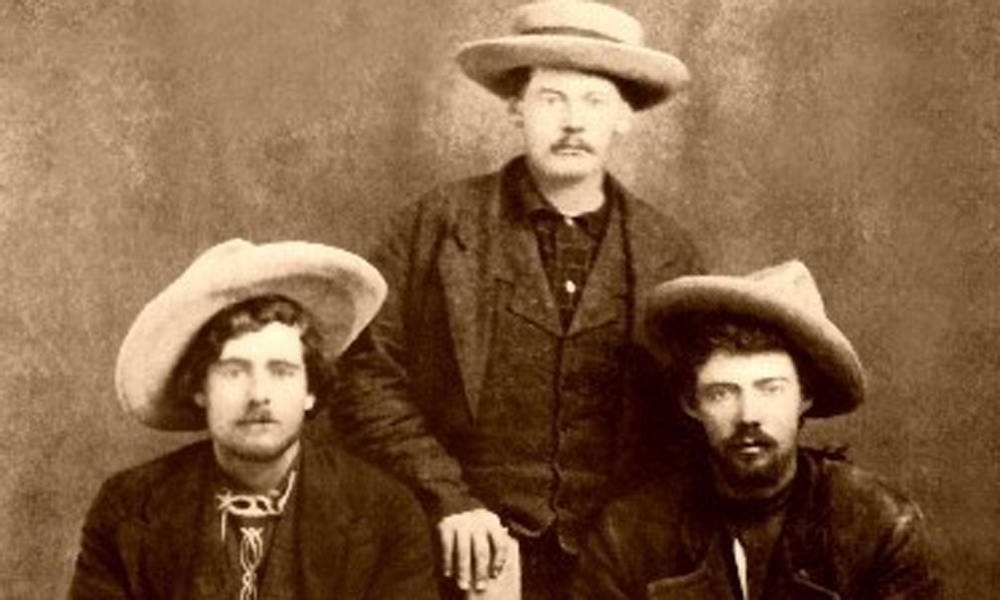

The same legislation that added blacks to the U.S. Army rolls, also called for the enlistment of up to 1,000 Indian scouts. Apaches, Cheyennes, Yavapais, Pimas, Crows, Arikaras and other members of other Indian tribes served alongside blacks and whites. A large number of the whites hailed from Europe with a strong representation from the British Isles and today’s Germany.

Regardless of origins, the burdens caused by a lack of manpower and the shortage of funds meant all labored under a divided command structure. Nominally, the commanding general who served in Washington, D.C., exercised control over the far-flung force. However, conflicts with the secretary of war regarding policy, and the fact that the Army staff was responsible directly to the secretary and not to the commanding general, caused internal friction and seriously impaired the effort to pacify the Indians.

nations home.

A further complication stemmed from geography. The post-war Army, as was the pre-war Army, was divided into regional departments. A commander assumed responsibility over each of these regions for operations in his area. As the Indians often moved across the boundaries of a given region, pursuit by troops from one command to another could prove a source of friction.

Another bone of contention arose from many of the officers in the post-war Army having held higher ranks during the war than their assignments afterwards. In addition, a system of brevets or honorary ranks given in recognition of meritorious service in the war caused jealousy, as many officers refused to acknowledge that someone who had been their subordinate during the war should now hold a higher rank than they held.

Despite such rifts in the first years following the Civil War, the focus of attention on the central and northern plains areas kept various commanders and several commands more than busy. U.S. Army infantrymen and their comrades in other branches were required to serve from Mexico to the Canadian border. These units stationed in the West particularly bore the brunt because they policed a territory comprised of well over one-half of the continental United States.

In this vast domain ran overland routes needing to be protected. The Smoky Hill Trail in Kansas, the Bozeman from Fort Laramie to the “diggings” in Montana, the Gila Trail across the Southwest from Texas to California and others required military escorts and patrols. Likewise, the construction of the railroad, including the Union Pacific-Central Pacific and the Santa Fe, made the protection of soldiers necessary. The tribes believed with a certain degree of validity, that these “iron horses” helped chase away the already diminishing game so vital to their existence. When not assaulting the encroaching railroad, American Indians occasionally targeted telegraph wires, requiring patrols to guard crews building or repairing the “talking wires.”

To protect these lines of communication and transportation, troops, especially foot soldiers, were stationed at strategic areas. In theory, this practice made it possible for them to respond quickly to any threat. The presence of posts also tended to encourage settlement because of the protection they afforded and because of the economic benefits that could be gained by supplying various goods to the soldiers and their families.

For the most part, however, Uncle Sam’s frontline soldiers remained for much of the year in garrisons, which more often than not were remote, tiny outposts removed from major settlements. For these frontier regulars and the women who shared their many trials, garrison duty could be tedious, primitive and lonely. And the distaff side labored under regulations, which classed them all, from “the colonel’s lady to Rosy O’Grady,” as “camp followers.” Yet, they bore children, raised families, made homes out of substandard government quarters and tended to the many thankless chores that fell to their lot. Not just silent observers, many women participated to the fullest. In several instances they left behind compelling memoirs of the “glittering misery” they endured and somehow transcended.

For the men, alcoholism and desertion were twin evils. Diversions and pastimes varied, occasionally bringing a respite from monotonous drill, construction duties and other daily routine. Sometimes the troops stepped in to preserve law and order or aid victims of natural disasters. Here, in addition to marital pursuits, they built the fort’s structures, kept the post supplied with firewood, cleaned equipment and even raised their own food to supplement the monotonous ration provided by the government.

As with the government-issue foodstuffs, the garrison itself lacked major variation. Routine fluctuated little and contributed to the formation of a structured community, one post resembling the next except for differences in local building materials. A parade ground usually formed the heart of the installation, serving as a sort of village green. Here stood the flagpole with Old Glory waving overhead as a symbol of government authority. Here the men assembled and carried out the rituals of their trade—guard mount, reviews and similar ceremonies.

At first these military evolutions relied on drill developed before the Civil War, but before long a new infantry manual, written during 1866-67 by a brave brevet major general from the Civil War, appeared to supplant earlier versions. While as-signed to the cadre at West Point, Emory Upton penned his Infantry Tactics, which soon became the standard for foot soldiers. In short order his two companion volumes for the cavalry and artillery, published in 1874 and 1875 respectively, became the Army’s holy trinity of tactics.

Along with the new manual came improved weapons. Although foot soldiers serving immediately after Lee’s surrender found themselves armed with the same muzzle-loading rifles they had carried against the South, efforts to introduce breech-loading firearms as replacements gained momentum. Foot soldiers were issued converted Civil War period muskets refitted with a sleeve in the barrel to reduce the cartridges from .58 caliber to .50 caliber and with the breeches cut out to insert new flip-up blocks.

These improved pieces of ordnance increased the rate of fire and proved popular with troops when they engaged an enemy used to the U.S. Army’s slower-loading muskets of the past. In 1867, infantrymen stationed in today’s Wyoming demonstrated the worth of these breech-loaders over older models of infantry armament. While engaged in a woodcutting detail for recently established Fort Phil Kearny, the foot soldiers and civilian contractors working the local forest came under heavy attack by a superior force of Lakotas, perhaps 1,000 warriors against some 40 whites.

Not long before, 80 men from the same post under Capt. William Fetterman of the 18th U.S. Infantry had been slaughtered. Now it appeared that a repeat of this previous disaster was about to occur. Fortunately for the besieged detail, they took refuge behind the beds of the wagons that had been removed from their running gears to provide conveyance for the trees being felled. Using the wagon boxes as a makeshift fortification, which gave the name to this engagement, the determined defenders repelled wave after wave of mounted Indians. They held their ground. Good marksmanship, grit and the new breech-loaders kept them from sharing the fallen Fetterman’s fate.

Such attacks near posts, however, were uncommon despite the Hollywood cliché. More typically, infantrymen and their mounted comrades in the cavalry set out in the spring or summer on campaigns that took them far from their barracks homes. These field operations often were the cause of considerable human suffering, and significant expense to the national treasury.Despite these costs, results regularly were unimpressive. For every noteworthy clash carried as a banner headline by the Eastern and European press, hundreds of other encounters went unnoticed or were all but forgotten. How the soldiers viewed the Indians they pursued as part of government policies offers one perspective into the lack of understanding that led to war between the two groups. In the final analysis, the Army was as much a victim as the Indians in the tragic period between the mid-1860s and early 1890s. Their lot was a thankless, thorny existence of boredom sometimes broken by the adventure of campaigning.

– Courtesy Fort Concho National Landmark –

John Langellier received his BA and MA in history from the University of San Diego and PhD from Kanas State University. He spent more than four decades in public history and museums and has published dozens of articles and books including Scouting with the Buffalo Soldiers: Lieutenant Powhatan Clarke, Frederic Remington, and the Tenth U.S. Cavalry in the Southwest, which was released by the University of North Texas Press in October 2020.