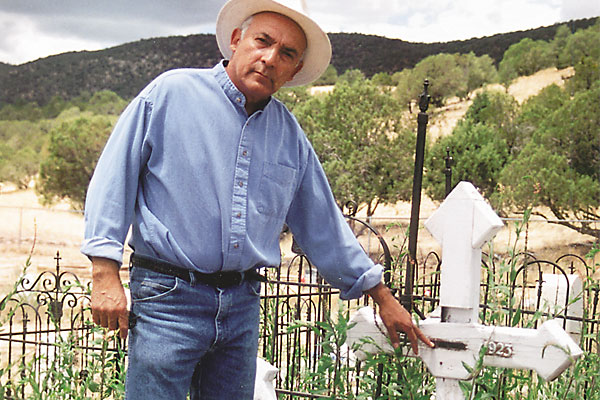

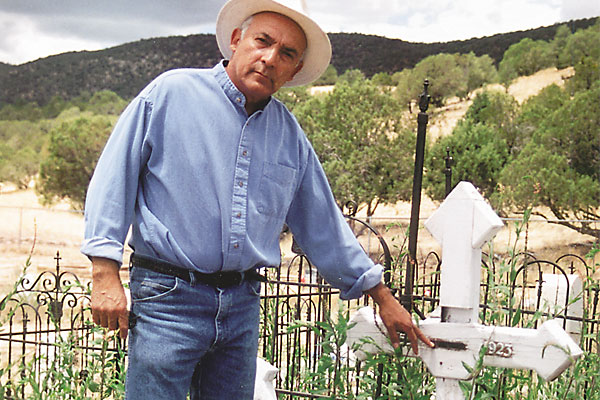

For most of his life, Henry Martinez had no idea he was part of history.

He grew up in the western New Mexico town of Reserve, population 336 today, where he thought not much important had ever happened. Like most kids, he left when he finished high school in 1964.

First the Air Force called to him, then he spent 25 years with the Social Security office in Phoenix, where he met and married Lori. They brought their two kids “home” to Reserve when he retired in 1992.

Henry ran a café for awhile and still owns and operates a gas station. He spent a lot of his time caring for Mom, who died last February, and Dad who is now 94 and needs a lot of help.

Henry had no idea his sleepy little town had been the centerpiece of one of the West’s most incredible gunfights. Or that the legendary story included a man named Epitacio Martinez who just happens to be Henry’s ancestor.

One day, New Mexico writer Howard Bryan came into the café and started talking about the book he was writing, The Incredible Elfego Baca; Henry was fascinated by the story he told. Then True West’s own Bob Boze Bell stopped by to chat, and he was all aflutter that Reserve didn’t have anything—not a plaque, not a hand-painted sign, not a spit on the floor—to mark the gun battle that took place there the last two days of October 1884.

Henry was not only sitting on a great big piece of Western history, but also his own family was part of it. So he began a seven-year quest to make sure everyone knows about Baca and the remarkable event that happened here 124 years ago.

One Mad 19 Year Old

Reserve was originally founded in 1870 by two families, including Henry’s. “But a few years later, the Texas cowboys showed up,” and things went downhill from then on, Henry says. The cowboys not only harassed, but also wounded and killed some of the local Hispanics. They even castrated one man called El Burro.

Poor Epitacio Martinez, Burro’s friend, was used for target practice. “But they were bad shots, and he lived,” Henry says of his great-great-grandfather. Word about the atrocities spread throughout the region and landed on the ears of a 19 year old in Socorro named Elfego Baca.

On October 30-31, 1884, this young man fought off 80 cowboys, during a 36-hour period, who reportedly fired more than 4,000 bullets and used dynamite and fire against him. Martinez says two cowboys were wounded and two others were killed, “but Baca came out without a scratch.”

In the end, Baca surrendered on his own terms—he refused to give up his gun—and was hauled off to jail in Socorro, where he was put on trial before an all-Hispanic jury and acquitted. Baca later became sheriff of Socorro, an attorney, deputy U.S. marshal, assistant district attorney and mayor of Socorro. He died in 1945.

The enormity of the fight and the unscathed condition of its target is breathtaking by any Western standard. “The story got swept under the rug because he was Mexican,” Henry says plainly. “If it had been a cowboy who took all that, the whole world would have known.”

To make his point, he gives this comparison: “Look at Wyatt Earp and the O.K. Corral. Wyatt fought against five men; it lasted 33 seconds and some 29 bullets were fired. Baca fought 80; it lasted 36 hours, and there were 4,000 bullets.”

Others have also taken note. Baca’s biographer Kyle Crichton wrote, “the life of Elfego Baca makes Billy the Kid look like a piker,” and Harvey Ferguson called him, “a knight-errant from the romantic point of view if ever the six-shooter West produced one.”

During a 1936 interview for the WPA American Life Histories project, Baca told writer Janet Smith: “I never wanted to kill anybody, but if a man had it in his mind to kill me, I made it my business to get him first.”

A Man on a Mission

Seven years ago, Henry Martinez decided, single-handedly, to correct history’s oversight of Elfego Baca. He started working on a museum for Reserve to commemorate Baca’s life. He found land and a sculptor—Sedona’s famed James Muir—to create a likeness. Next year, he hopes to launch an annual October festival.

The sculpture is a jacal with a bronze Baca—all six-foot-two-inches of him—stepping out with a six-gun in his hands. (Baca stood five feet, seven inches tall, but outdoor sculptures are larger than life; this bronze is one-tenth larger.)

The 800-pound sculpture was unveiled in May and financed through state grants. “When a tourist comes up to read the plaque, he’s looking down the barrel of the gun,” Henry notes.

Henry has received more than $250,000 so far and is looking for federal help to build the $7 million museum. He’s thankful the New Mexico legislature has been so supportive.

Henry is a natural Old West Savior—it fits into his philosophy of life: “I believe that if you want to do something, try it,” he says. “Don’t sit and wonder if you could have. I don’t want to die thinking, I should have done something; I didn’t try.”