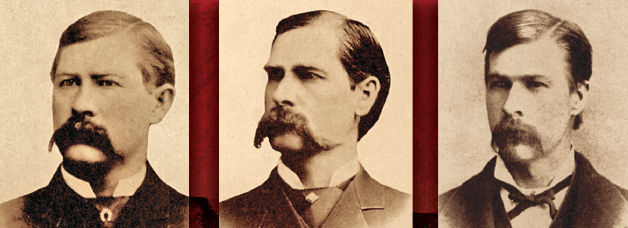

The Cowboys were the Old West’s biggest outlaw gang. In Arizona and New Mexico, they committed highway robberies, waylaid Mexican pack trains, stole thousands of heads of cattle on both sides of the international border and murdered at least 35 men. The Cowboys worked closely with dishonest ranchers who helped them smuggle and conceal purloined livestock, and with crooked butchers and cattle dealers who were happy to buy cheap, stolen beef. They were unopposed in Arizona Territory until they ran headlong into the disreputable but deadly Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan Earp, and their dentist-gambler pal, Doc Holliday.

The Cowboys’ genesis lay in the savvy and the six-shooters of John Kinney, one of the most notorious outlaws of the American Southwest. Several desperadoes who became leading lights of the Cowboys rode with John Kinney in Texas and New Mexico Territory, playing bloody roles in the El Paso Salt War and the Lincoln County War. Two of them were Bob Martin and Curly Bill Brocius. In November 1878 they broke jail near El Paso and fled to southeastern Arizona Territory. It was an isolated frontier, with no settlements, no towns, no border, no law enforcement—just mountains and desert and mesquite and Apaches.

During the next two years, Bob Martin and Curly Bill were joined by numerous badmen and fugitives, including desperadoes John Ringo, Pony Diehl, Cactus Bill Graham, Sherman McMaster, Jim Wallace, Billy Leonard, Jim Crane, Harry “the Kid” Head, Luther King, Frank Stilwell, Pete Spence, Jimmy Hughes and Dick Lloyd. They formed a loose-knit gang of about 100 outlaws which operated in small bands on both sides of the border. Their number would eventually grow to as many as 200. Mexicans dubbed them “Tejanos,” or Texans; Americans called them the Cowboys. Although the term “cow-boy” had been in common use in New England in the late 1700s, by 1879 it took on a sinister meaning in Arizona and New Mexico. As one frontier journalist explained, “The cowboy is a cross between a vaquero and a highwayman.”

While most of the Cowboys were Anglo, the band included some Hispanics, including Florentino Sais, a mestizo with strong Indian features. He first came to prominence as a member of the gang of Guadalupe Celaya, a Mexican revolutionary who morphed into a bandit. In September 1878 Sais, Celaya and other members of the gang committed one of frontier Arizona’s most infamous murders. At Barrel Springs in Davidson Canyon, 33 miles southeast of Tucson, they ambushed and killed Captain John Hicks Adams and his mining partner, Cornelius Finley. Adams was one of California’s most famous lawmen and bandit hunters and had served as sheriff in San Jose. He and Finley had just been sworn in as deputy U.S. marshals. Florentino Sais managed to escape justice, but more than three years later he would meet his fate in the deadly guns of Wyatt Earp.

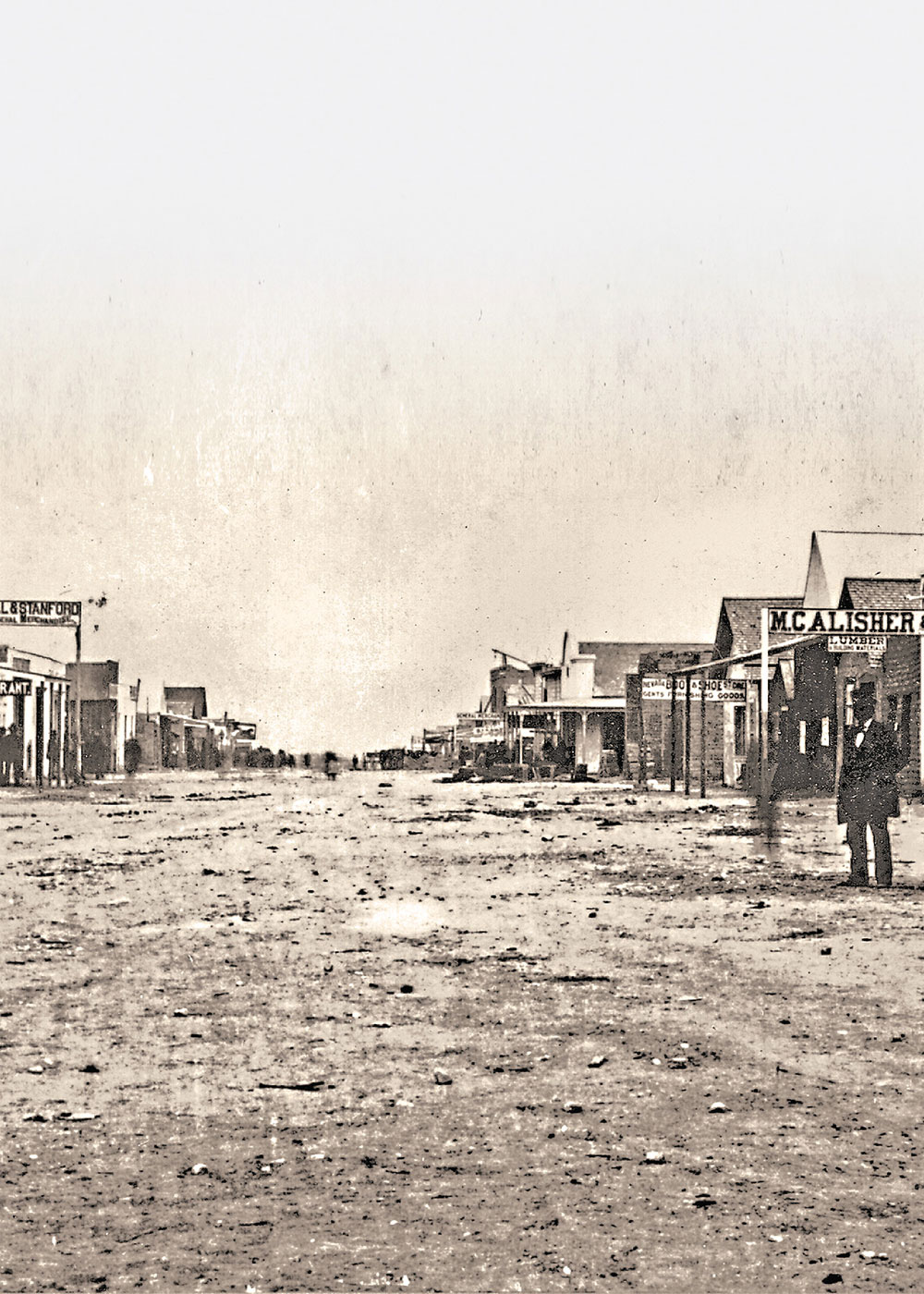

In 1878, the mining camp of Tombstone sprang up, and it quickly became the Cowboys’ favorite watering hole. On the night of April 8, 1879, Charley Snow, a killer and rapist who rode in the Lincoln County War, got liquored up in Tombstone. He soon ran into Frank Patterson, a 25-year-old fellow Cowboy who owned a ranch next to that of Tom and Frank McLaury on the Babocomari River. The pair had a violent quarrel which ended when Patterson drew his pistol and shot Snow down. One of the witnesses later said that the New Mexico desperado “was not dangerously wounded.” Officers arrested Patterson, but because Snow recovered from his wound, and the fracas more or less resembled mutual combat, Patterson escaped indictment.

Before long, Patterson was involved in a much deadlier affair. On November 9, 1879, an old prospector, John Van Houten, was found bludgeoned to death near the Brunckow Mine, not far from Charleston, a new mining camp situated nine miles southwest of Tombstone. Deputy sheriffs quickly arrested three of the Cowboys—Frank Patterson, Pete Spence and Frank Stilwell—as well as three other suspects. They were accused of trying to jump Van Houten’s mining claim. As was customary in that time and place, all gained their release due to lack of evidence. The three Cowboys—especially Stilwell and Spence—would be heard from again and again in the years that followed, and Stilwell would not survive his final encounter with Wyatt Earp.

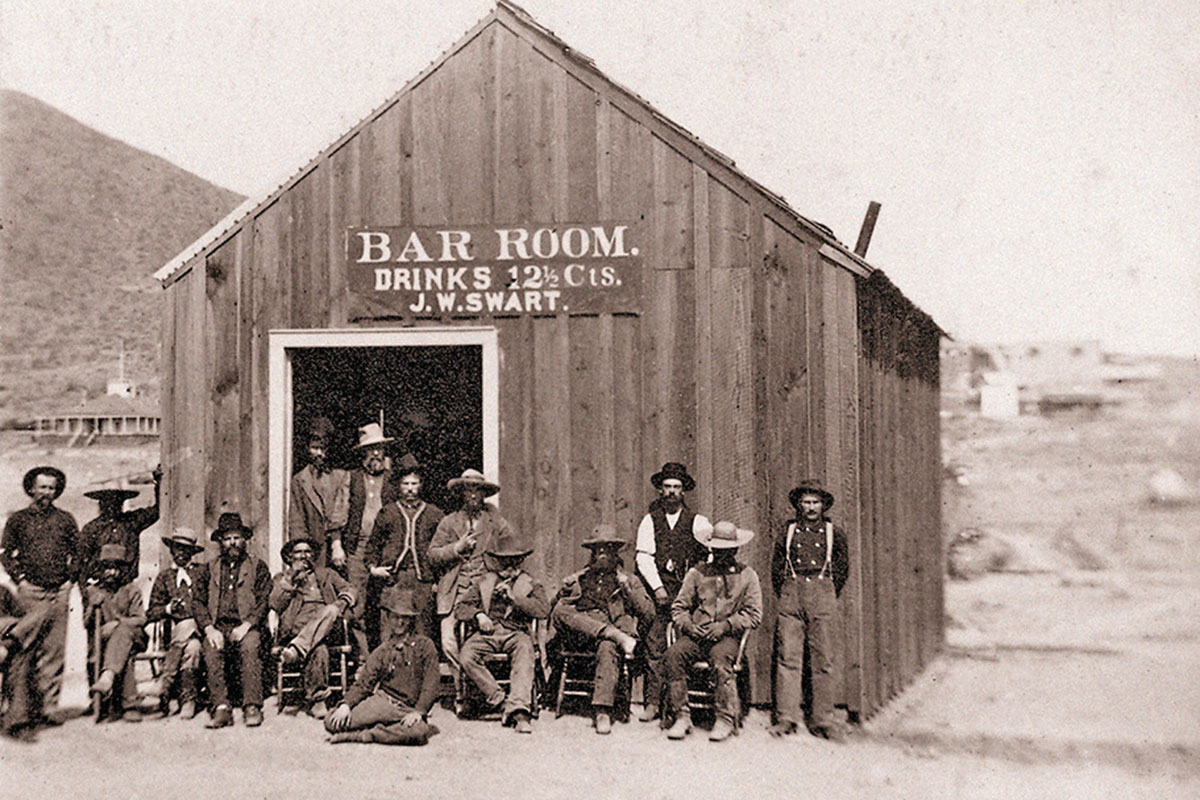

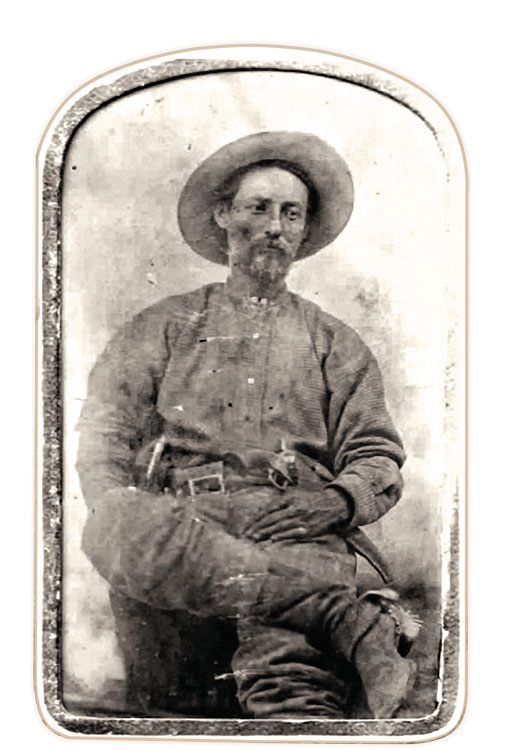

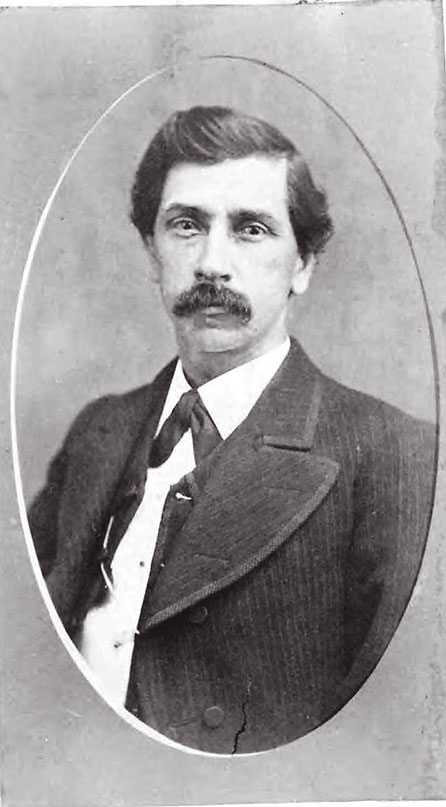

These outlaw cowboys are identified only as “New Mexico Rustlers” on this circa 1880 cabinet card. The man standing is John Kinney, who led a gang of horse thieves and cattle rustlers in New Mexico Territory during the 1870s-80s.

Bob Martin and Curly Bill made frequent raids across the border to steal cattle from Mexican rancheros. One of their targets was the Corralitos Mining and Cattle Company. Its owner, Ramon Lujan, had been joined by one of his American partners, Major George B. Zimpelman, whose unfair treatment of Hispanics had triggered the El Paso Salt War in 1877. Zimpelman, born in Germany in 1842, had emigrated to Texas with his parents at age 16. Tough as nails, he served with great distinction in Terry’s Texas Rangers during the Civil War and received multiple wounds in combat. Later he won election as sheriff in Austin, holding office until 1876. Zimpelman became wealthy investing in businesses, mines and ranches in Texas and Mexico. By the summer of 1880 he had moved to Mexico to help manage the Corralitos operations. Because of the repeated Cowboy raids, Zimpelman brought several men with him from El Paso, among them Thomas Moad, a former stage driver and Texas Ranger, who, three years later, would be the first El Paso policeman to be killed in the line of duty. These Texans, along with Mexican recruits, were known as Zimpelman’s Guards. Martin and Curly Bill had picked a tough outfit to tangle with.

In early August 1880, Bob Martin, Curly Bill and Miller McCallister, the latter a crooked butcher, with several other Cowboys, rounded up 300 head of cattle on the Corralitos ranch and started for the border. The theft was quickly discovered and Major Zimpelman, with Tom Moad, a black cowhand, and 14 of his Guards and vaqueros, took to the saddle. They cut the rustlers’ sign and trailed them north. In Janos, Mexican volunteers joined the pursuers and they spent two more days tracking the outlaws across the border. On August 8 the posse found the outlaws holed up in a stockade in the mountains of New Mexico’s bootheel. According to James C. Hancock, a pioneer who knew some of the Cowboys, their fortress was made of posts that enclosed a small cave under an overhanging boulder. Hancock identified Curly Bill, Cactus Bill Graham and an old man named Scotty as three of the Cowboys trapped in the stockade.

— Charles A. Farciot, courtesy Arizona Historical Society —

Martin and his men were, as always, heavily armed with six-shooters and Winchesters. While some of Zimpelman’s Guards quickly rounded up the herd of stolen cattle, the rest surrounded the stockade. The Cowboys immediately opened fire and the Guards returned it, shot for shot, giving Miller McCallister a minor flesh wound in the neck. According to Hancock, “The Mexicans would put their hats on a stick and every time Bill Graham would ‘cut loose’ at it, until finally Curly Bill told him to quit shooting at the hats as the Mexicans were doing that so as to get them to shoot all their cartridges away and the clean them up, but Graham could not resist and Curly Bill told him if he did not quit he would take his cartridges away from him, which he eventually did.”

Above the din of gunfire Curly Bill shouted to Graham, “Now, if they make a rush on us, I will give your cartridges back but not until they do.” Explained Hancock, “Every time a Mexican showed himself the least bit Curly Bill would get him. Curly Bill never lost his nerve or got ‘rattled’ under any circumstances.” The Cowboys winged one Mexican and the black cowboy and wounded two of the posse’s horses. Finally Tom Moad caught a glimpse of Curly Bill and squeezed off a rifle round. The bullet grazed the side of Curly Bill’s head and knocked him to the ground. But the Cowboys were unfazed and stubbornly defended their stockade with rifle- and pistol-fire. Zimpelman finally decided to withdraw for fear of having some of his men killed. The Cowboys brought the wounded Curly Bill to safety and sent for a doctor in Silver City. Curly quickly recovered. The governor of Chihuahua complained about the raid to U.S. authorities, charging that the outlaws “belong to the band which is under the leadership of the notorious criminal Robert E. Martin.” He pleaded for “speedy pursuit and punishment” and added, “otherwise, between these outlaws and the Indians, cattle raising…will be crushed out entirely on the northeastern frontier of the state.”

A few weeks later, Mexicans somehow managed to capture Bob Martin and he was jailed in Ascension. Probably through bribery, a local judge promptly released him. An outraged Mexican lawyer wrote to the governor of Chihuahua: “If the outlaw Martin, who is the leader of these Texans, had not been unjustly acquitted, we should now be at peace; though Martin was arrested by order of the government, he was protected by the district judge, and we, whose blood is now being shed, are today suffering the fatal consequences of that protection.” Pleading for help from the Mexican government, he railed against “the scandalous deeds which are constantly perpetrated by Texan outlaws” and warned of “the total ruin of all the inhabitants, for they have already lost all their horses, and the greater part of their meat cattle.” But Bob Martin escaped back to his hideout in New Mexico. He did not live long. Three months later he was slain by fellow Cowboys in a quarrel over stolen horses.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

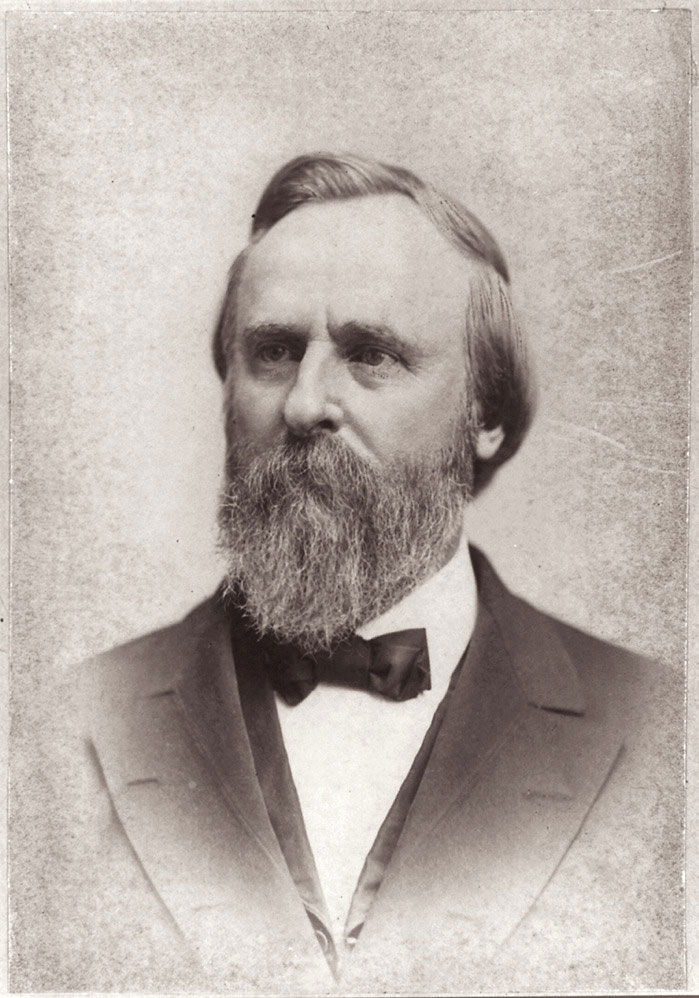

With Martin’s death, Curly Bill Brocius quickly came to the forefront as the most notorious Cowboy leader. But the Cowboys’ most brazen episode did not involve smuggling or raiding or shooting. In October 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes made a hugely publicized railroad excursion to the Pacific Coast. His trip back to Washington, D.C., was on the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railroads, which at that time had not been completed. After visiting Yosemite and Los Angeles, California, Hayes entrained for Arizona and reached Tucson on October 24. Large crowds greeted the president, who was accompanied by numerous dignitaries—including Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman—and their wives. After a carriage tour of the Tucson’s Old Pueblo, they were to proceed east through San Simon station to the railhead near Lordsburg, New Mexico. From there the presidential party would board horse-drawn U.S. Army ambulances for the 180-mile overland journey to the Santa Fe railhead in San Marcial, New Mexico. It was an extremely risky trip through the very heart of Apacheria. Reported the Phoenix Herald, “The party traveled by special train, one engine, baggage car and three coaches and were unaccompanied by a military escort, and this through a frontier country—something that the ruler of no other nation on the globe would think of doing.”

But the danger did not come from Apaches. Just as the president’s party was to depart Tucson that evening, they received a message that the Cowboys had threatened to stop the train when it reached San Simon station. General Orlando Willcox, commander of the army in Arizona, boarded the coaches with several of his staff. At Benson the train stopped and Gen. Willcox telegraphed ahead to Fort Bowie. He ordered a detachment of the 6th Cavalry to ride to San Simon, 14 miles northeast of the fort, to guard against the Cowboys. When the train reached Willcox—a stop named after the general—he had his telegraph operator tap the line and send a confirming message to Fort Bowie. This message did not go through, either because the lines were accidentally down or the Cowboys had cut them. Then General Willcox called for civilian volunteers to accompany the president, and 25 armed men quickly scrambled aboard. When they reached San Simon that night, Willcox ordered the train to keep on without stopping. A Tucson journalist who accompanied the train reported from the railhead in Lordsburg that “happily, nothing occurred, the party arriving here in good spirits, most of them being purposely kept in ignorance of the previous night’s adventures.”

Fresh from threatening the President of the United States, a group of Cowboys—which included Curly Bill Brocius—turned their horses toward Tombstone. As they loped their Texas mustangs across the cactus-studded desert, looking forward to raising hell in Tombstone, they could not have imagined what waited for them. The Cowboys’ epic confrontation with Wyatt Earp and his brothers was about to begin.

From Parson’s Diary

More Cowboy Bullying

January 10, 1881

“Some more bullying by the cowboys. ‘Curly Bill’ and others captured Charleston the other night and played the devil generally—breaking up a religious meeting by chasing the minister out of the house—putting out lights with pistol balls and going through the town. I think it was tonight they captured the Alhambra saloon here and raced through the townfiring pistols.”

In a further confirmation, in his May 13 entry, Parsons encounters an itinerant preacher who he calls McKane (actually Joseph McCann). “He is the one Curly Bill made dance and commanded to preach and pray, shot out lights, etc., at Charleston recently. He won’t discuss the matter.”

The Cowboys

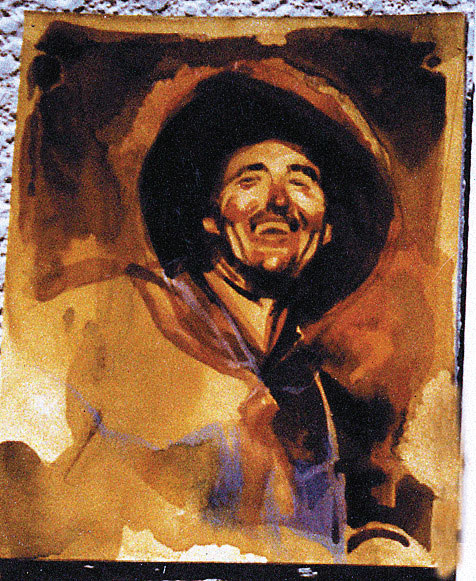

— Richard Lapidus Collection —

the Cowboys.

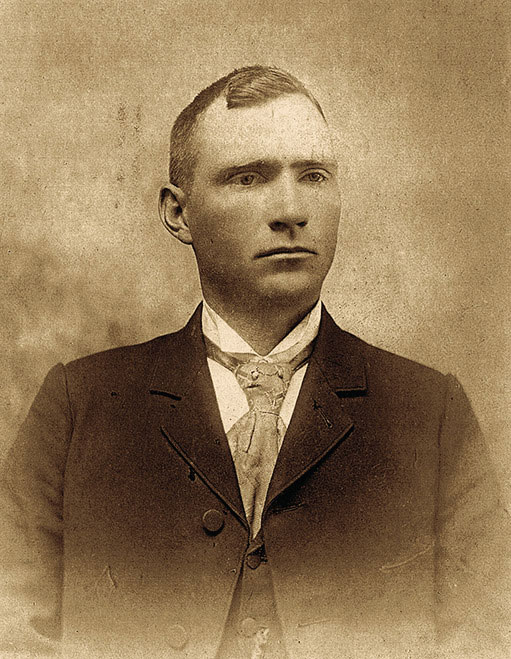

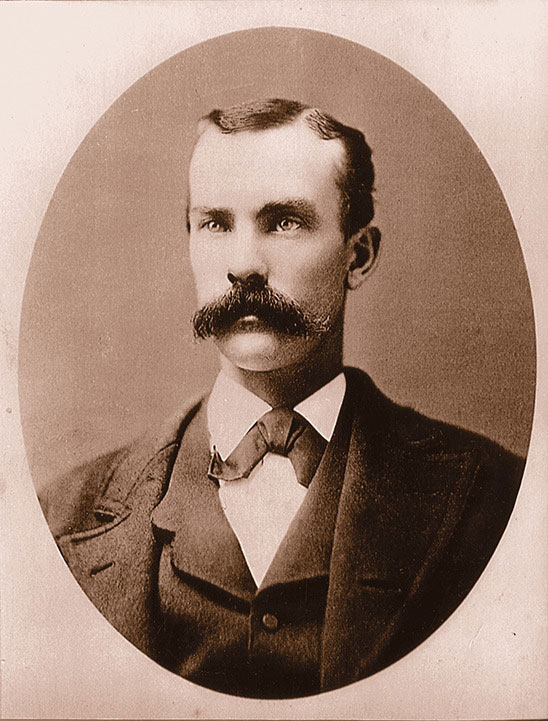

— Author’s Collection —

— Arizona Historical Society —

— Courtesy Roy B. Young —

— Author’s Collection —

— Author’s Collection —

— David Johnson Collection —

“Ride the Devil’s Herd: How the Cowboys Ruled Tombstone before Wyatt Earp” by John Boessenecker is an exclusive excerpt from the award-winning San Francisco author’s newest book, Ride the Devil’s Herd: Wyatt Earp’s Epic Battle Against the West’s Biggest Outlaw Gang, to be released by Hanover Square Press in March 2020.